FICTION

Virgil Wander, by Leif Enger

Step into the pages of Virgil Wander and walk with the quirky, charming citizens of Greenstone, Minnesota, where normal life is anything but and Hard Luck Days is actually a celebrated event. Vintage theater owner and city clerk Virgil Wander drove through a guardrail and into Lake Superior and lived to tell the tale, although he wasn’t quite the same. Fable-like happenings prevail — a local sports hero disappears into the wild blue yonder; an elderly kite flyer enchants all; a movie star with seemingly sinister motives returns; a massive sturgeon lurks near the shore; and who is that mysterious, silent man Virgil occasionally spies standing on the water? Readers will be captivated by the warmth, wit and whimsy infused in each line.

Scribe, by Alyson Hagy

Folkloric, tragic and surreal, you might have to sit in stillness long after the final page of Scribe just to absorb Hagy’s evocative and achingly beautiful prose. Deep in Appalachia following a civil war and a pandemic, there remains a society under authoritarian rule. A woman living alone in a farmhouse has the ability to write letters for others who barter with the goods she needs to survive. She is haunted by her own misdeeds and a violent past that raises its head when a strange man requires her services in crafting and delivering a fateful letter. Her journey is a dream-like odyssey in a dystopian landscape that’s lyrical, desolate and wonderfully strange.

Man with a Seagull on his Head, by Harriet Paige

Ray Eccles’ mother has died and he is on his knees at the shore when a seagull falls from the sky and lands on his head — a scene witnessed by a woman walking on the beach. When he gets home, all he can do is paint this woman over and over again, creating the exact same picture every time. Discovered by “Outsider Art” collectors, he moves in with them and continues to paint, becoming a celebrated artist. Paige’s novel is a quirky, interesting, original story of a life lived one foot in front of the other, when nothing else matters but what is in front of you.

Little, by Edward Carey

After the death of her parents, a tiny odd-looking girl named Marie is apprenticed to an eccentric wax sculptor and whisked off to the seamy streets of Paris, where they meet a domineering widow and her quiet, pale son. Together, they convert an abandoned monkey house into an exhibition hall for wax heads, and the spectacle becomes a sensation. As word of her artistic talent spreads, Marie is called to Versailles, where she tutors a princess and saves Marie Antoinette in childbirth. But outside the palace walls, Paris is roiling: The revolutionary mob is demanding heads, and . . . at the wax museum, heads are what they do. Book clubs will enjoy discussing this wry, at times macabre, read.

A Well-Behaved Woman, by Therese Anne Fowler

In this thought-provoking fictional account, Alva Smith — her Southern family destitute after the Civil War — marries into a Gilded Age dynasty: the illustrious, wealthy but socially shunned Vanderbilt family. Ignored by New York’s old-money circles and determined to win respect, Alva designed and built mansions, hosted grand balls, and arranged for her daughter to marry a duke. She also defied convention for women of her time, asserting power within her marriage and becoming a leader in the women’s suffrage movement.

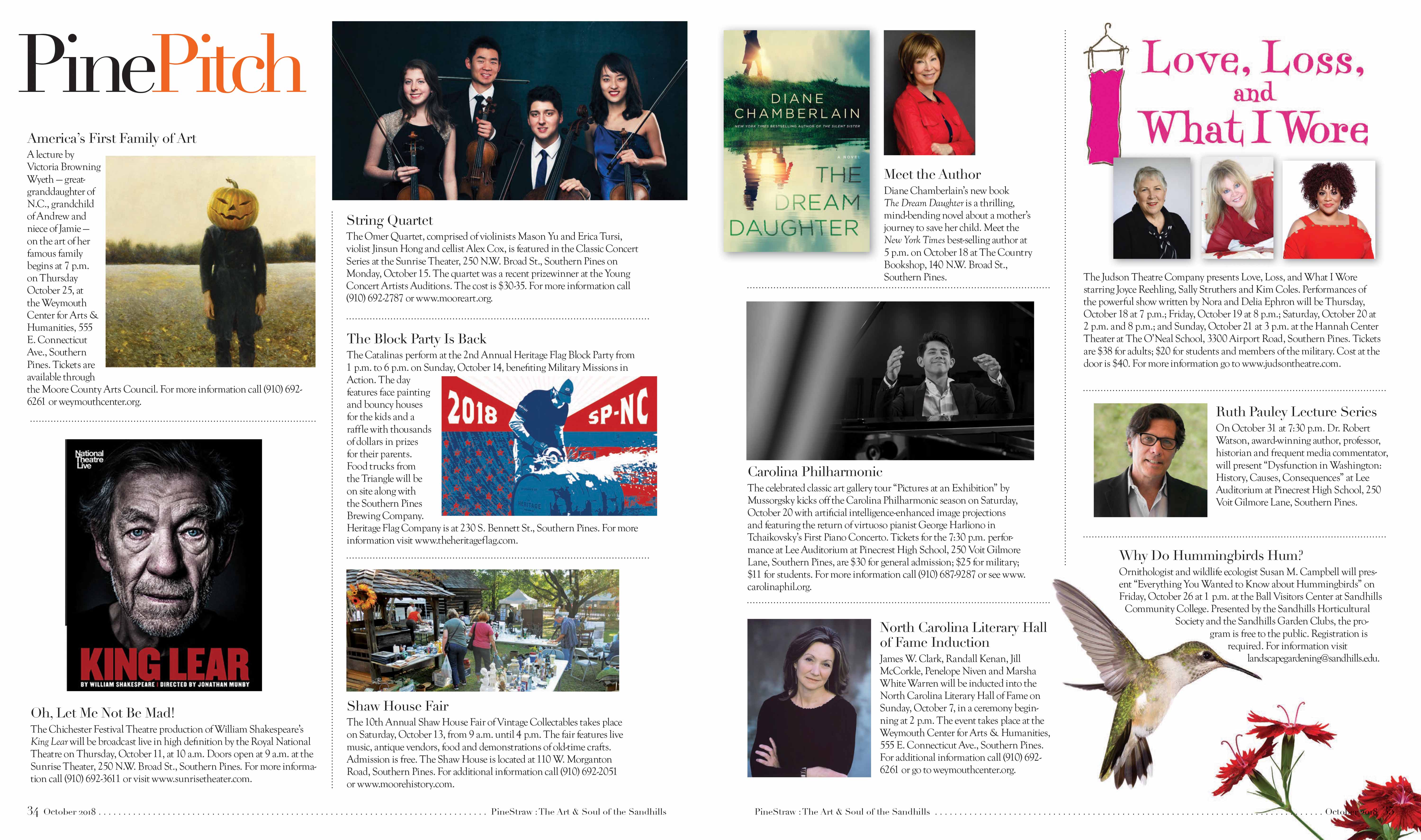

The Dream Daughter, by Diane Chamberlain

In 1970, Caroline Sears receives the news that her unborn baby girl has a heart defect. She’s devastated until she learns that something can be done. Something that will shatter every preconceived notion Caroline has. Something that will require a kind of strength and courage that she never knew existed. Something that will mean a mind-bending leap of faith. A rich, breathtaking novel about a mother’s quest to save her child, unite her family, and believe in the unbelievable. Chamberlain pushes the boundaries of faith and science to deliver a novel you will never forget.

The Traveling Cat Chronicles, by Hiro Arikawa

Nana is a stray cat named for the spot on his tail that looks like the number seven (nana) in Japanese. His adoptive owner is Saturo, who nurses him after he’s been hit by a car. Saturo and the cat travel to distant towns to visit Saturo’s friends as he tries to find Nana a new home. Narrated in turns by Nana and by his owner, this funny, uplifting, heart-rending story of a cat is nothing if not profoundly human.

NONFICTION

In the Hurricane’s Eye: The Genius of George Washington and the Victory at Yorktown, by Nathaniel Philbrick

The thrilling story of the Revolutionary War’s decisive battle from The New York Times best-selling author of In the Heart of the Sea and Valiant Ambition. In the Battle of the Chesapeake, a French admiral foiled British attempts to rescue its army led by Lord Cornwallis. This naval battle, masterminded by Washington but fought without a single American ship, was largely responsible for the independence of the United States. A riveting and wide-ranging narrative, full of dramatic and unexpected turns, In the Hurricane’s Eye reveals that the fate of the American Revolution depended, in the end, on Washington and the sea.

The Ravenmaster: My Life with the Ravens at the Tower of London, by Christopher Skaife

The Yeoman Warder and Ravenmaster, Skaife lives at the Tower of London with his wife and writes the first behind-the-scenes account of the legendary ravens at one of the world’s eeriest monuments. He lets us in on his life as he feeds his birds raw meat and biscuits soaked in blood, buys their food at Smithfield Market, shines a light on the birds’ pecking order, social structure and the tricks they play on us. Skaife shows us who the Tower’s true guardians are.

CHILDREN’S BOOKS

Dreamers, by Yuyi Morales

Stunning mixed-media illustrations beautifully tell the story of a woman who journeys with her son to the United States to meet his grandfather. Her life is changed forever when she takes her child into a public library for the first time. Beautiful, simple and brilliantly told, Dreamers is a must read for anyone who has a story to tell. (Ages 4-6.)

My Dog Laughs, by Rachel Isadora

From the ever-amazing Isadora comes this perfect “getting a new dog” book. Simple lovely illustrations share the adventures of many different children and their new dogs as they choose a name, select a leash, train, care for, play, and laugh together. (Ages 3-6.)

A Long Line of Cakes, by Deborah Wiles

With five brothers in tow and a family who seems to move every time she makes a new friend, Emma Alabama Lane Cake is justifiably reluctant to make new friends when her family opens the Cake Cafe right between the post office and Miss Mattie’s Mercantile. But Emma has never met Ruby Lavender, and Ruby has a different plan. Sweet, silly and absolutely the most wholesome thing since the Little House on the Prairie series, A Long Line of Cakes is just the perfect thing for young readers or for families to share together. (Ages 8-12.)

Thundercluck! by Paul Tillery IV

A magic mishap grants the power of thunder to a chicken, who must face an evil chef in this debut novel from Tillery and co-illustrator Meg Wittwer. Thundercluck, the chicken of Thor, first appeared in an award-winning animation. The short film screened in over 50 festivals, including the San Diego Comic Con Film Festival, and the Con Carolinas Film Festival, where it won the 2015 Best Animation Award. “I wanted to tell the kind of story I would’ve loved at that age,” Tillery says. “It’s a quirky story, because I was a quirky kid.” Author/illustrator Tillery, who lives in Raleigh, North Carolina, and Savannah, Georgia, where he teaches animation at the Savannah College of Art and Design, will share his adventures in animation, illustration, writing and quirky comedy at The Country Bookshop on Monday, Nov., 5 at 4 p.m. (Ages 7-12.) PS

Compiled by Kimberly Daniels Taws and Angie Tally