When the canvas is a load of bricks

By Jim Moriarty

It’s a small space to launch big art. Scott Nurkin, muralist and musician, keeps an office around the corner from a giant likeness of the late Dean Smith he painted on the side of a building in Chapel Hill just because he thought it needed doing. Behind his desk in the Mural Shop is a wall of books from Old Masters to birds; golf to jazz; The Beastie Boys to Ansel Adams. The latter seems particularly appropriate.

At one time there was a poster that hung in Adams’ darkroom — it may still — that was entitled “Ted Orland’s Compendium of Photographic Truths.” Orland had once been an assistant to the master landscape photographer. The highlight of the poster is a picture of Adams peeking out from beneath the cloth of his view camera that’s positioned to take a photo of what looks like a class of fourth graders. The caption says, “Even Ansel Adams had to earn a living.”

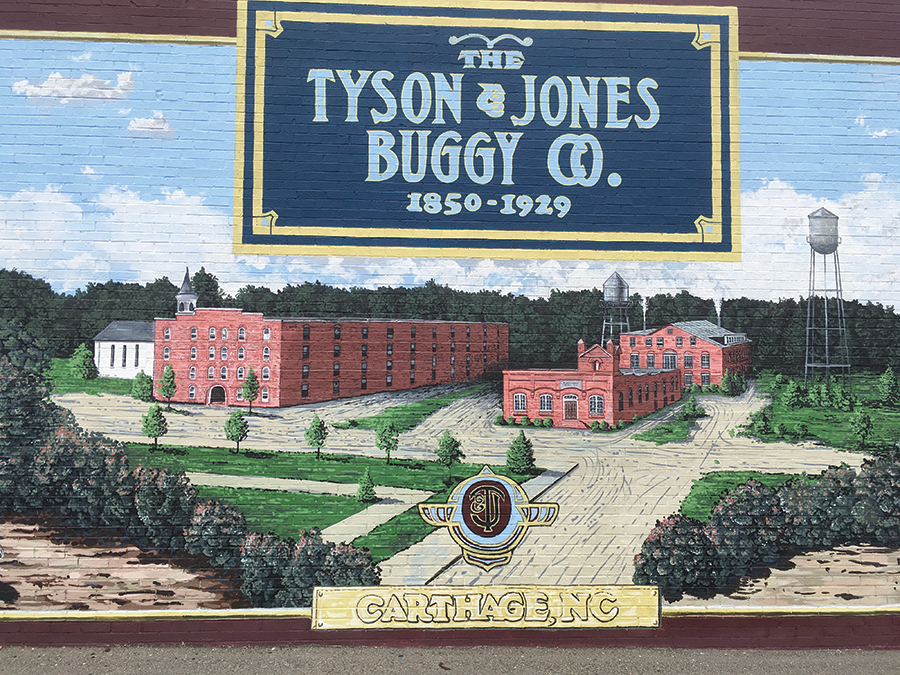

Nurkin doesn’t have a view camera. He’s got an old Ford Ranger that needs a little work and enough extension ladders to storm the Alamo. He was last seen in Moore County on top of a cherry picker painting “Pinehurst” on the side of the smoke stack at the new brewery. Hey, it’s a living. In Carthage, his work includes an ode to tobacco fields and farmers on the side of the Marion Building; a tip of the cap to the Tyson and Jones buggy company in the parking lot of Fred’s Low Price Leader; and an homage to a World War I flying ace on the wall by Dunk’s Gym. Hey, it’s art, too.

“You arrive on the scene and there’s a giant brick wall,” he says. “I pressure wash it and put masonry primer down. From there I have a drawing, something to go by. Then I sketch the imagery out on the wall and over the next few days, weeks, months, keep painting and painting and painting until you get to the finish line.”

Nurkin grew up in Charlotte, the middle boy in a handful (five) of them. He went to Myers Park High School and Charlotte Latin, then Rhodes College in Memphis. After taking a “Semester at Sea” circumnavigating the globe, Nurkin began searching for a university with a stronger emphasis in art, winding up at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill where he ultimately got his bachelor of fine arts degree. During his junior year he studied in Florence at the Lorenzo de’ Medici School of Art. “That’s where I really learned how to paint. It was intimidating as hell, going from being one of the stronger artists to a place where everybody in the classroom wants to excel,” he says. “I was terrified a lot of the time.”

When he got back to the states he began working as an intern for Michael Brown, a Chapel Hill mural painter 20 years Nurkin’s senior. Brown, also a UNC graduate, spent time teaching art in New York and working at the Guggenheim Museum before returning to North Carolina. “At some point someone asked me to do a mural. It was a big one, a four-story tall one,” Brown says. “So, I said, ‘OK,’ and the phone has been ringing for the past 30 years.”

After graduation in 2000, Nurkin needed a job and Brown needed an assistant. “After the apprenticeship I begged him to have me be his full-time apprentice, which he agreed to do for some reason,” says Nurkin. “At the time, I was also touring as a musician so I was really loath to get an actual job. I would work, go out on tour for a couple of weeks and then come back and work a little bit.”

Nurkin is the drummer in a pair of Triangle-area bands, Dynamite Brothers and the Birds of Avalon. Both released new CDs in the past year. A childhood friend of his, actor Ben Best, says, “He’s one of the best, if not the best, drummers in North Carolina.” Best is a graduate of the North Carolina School of the Arts and his friends there included Danny McBride and David Gordon-Green who made a show for HBO called Eastbound and Down. “When they first started out they didn’t have any budget for music so we did a bunch of music for them,” says Nurkin. “They’ve been good to us since then, put some of our songs in their show and some of their movies as well.”

In 2003 Nurkin and Brown went their own artistic ways, amicably. “I came to a crossroads when I left working for Michael. Do I want to do music full time or do I want to pursue art full time?” he says. At first, music won. “I started touring heavily. The Birds of Avalon had a modicum of success. We very quickly got signed to a label out of California. They sent us to Europe a couple of times. We got to tour with some pretty big names. The Flaming Lips. The Raconteurs. Big Business. MudHoney. We were the perpetual opener.”

In 2010 Nurkin married Erin, who he met at Chapel Hill’s now defunct pizza institution, Pepper’s. “Every Chapel Hill musician from the ‘80s on, some member of the band worked there,” says Nurkin. A year later they had their daughter, Finch, and the road lost some of its appeal. “We all kind of grew up,” he says. “Jumping in a van and touring, it’s just an insane thing to do in 2019. Touring is the one hour you’re on stage. The other 23 hours can be a nightmare. You’re in a van with six other people who smell terrible, you eat crappy food, you sleep on the floor. It’s not like we’re Led Zeppelin in a giant plane and bus. That one hour is the pay off and you go, ‘Oh, this is why I’m doing it.’ There was definitely a fire from 2005 to 2009. We were really hungry. We really wanted it. It just didn’t work out. I sure as hell tried. What’s living if you don’t do it?”

There remained that minor detail of making a living, and Nurkin refocused his energy into painting. “It would have been a lot easier over the last seven or so years if I hadn’t had a competitor,” laughs Brown, “but if you gotta have a competitor you might as well have one you’re proud to be associated with.”

Nurkin’s murals have shown up in places like the Bahamas — a friend from that “Semester at Sea” hired him for a couple of projects in Cape Eleuthera — and Coconut Creek in Florida. In downtown Chapel Hill he painted a mural-sized postcard “Greetings from Chapel Hill,” another labor of love. He was part of a mural festival in Charlotte. “They had 20 artists, five international, five national, five regional and five local. They give you a wall and you can paint whatever you want. We had three days to do a mural.” Nurkin devoted his wall to North Carolina’s endangered species. Because the painting had to be done quickly, he used spray paints, a technique he employed on his tobacco field in Carthage, too.

“I shunned it for so many years,” he says. “Then I started seeing these people doing these incredible, hyper-realistic paintings because, with aerosol, you can fade it in, spray it. The material works so much better for certain applications. You can work very, very fast.”

One of the stories Nurkin likes to tell is about an art professor at UNC who asked his students to raise their hands if they actually wanted to be a professional artist. Nurkin was the only one to put up his hand. It’s still there.

“Painting and drums were the two things I couldn’t not do,” he says. “It’s never occurred to me not to do them.” PS

Jim Moriarty is senior editor of PineStraw and can be reached at jjmpinestraw@gmail.com.