THE SILVER SCOT'S SHANGRI-LA

The Silver Scot’s Shangri-La

Legendary Great Tommy Armour and Pinehurst

By Bill Case • Photographs from the Tufts Archives

He had survived — a luckier fate than that suffered by millions of World War I soldiers — but his battlefield injuries were grievous. A German mustard gas explosion had totally blinded the young Edinburgh native. One lung was badly burned by the gas. In another engagement, shrapnel from an enemy shell caused serious injuries to his head and left arm, necessitating the implanting of metal plates. Lying battered and helpless in a British military hospital bed, the odds seemed heavily against Tommy Armour ever resuming a normal life.

Serving in the Black Watch Regiment’s tank corps from 1914 to 1918, Armour rose from the rank of private to staff major and achieved widespread notoriety for his machine-gunning prowess. He assembled, loaded and fired his weapon faster than anyone in the Army. This singular talent required superior manual dexterity but, in addition, his hands were remarkably strong: While singlehandedly capturing a German tank, Armour strangled the tank’s commander to death when he refused to surrender.

Prior to the war, those formidable hands had served him well. Among his talents, Armour was a virtuoso violinist and a high-level bridge player, but his favorite pastime was golf. Armour, his older brother Sandy, and lifelong friend Bobby Cruickshank toured Edinburgh’s Braid Hills Golf Course at every opportunity. “In the summer,” Armour later recalled, “I would be on the first tee at 5 a.m. and in the evening . . . play a couple of rounds.”

Throughout his convalescence, Armour kept up his spirits by dreaming of playing golf again. While it took six months, sight gradually returned to his right eye, though he remained blind in his left. The recuperating 23-year-old would play golf again, but could his limited vision scuttle any hope of regaining his previous form? The preternaturally confident Tommy Armour believed otherwise.

Armour joined Edinburgh’s Lothianburn Golf Club with the expectation of not just recovering his game but elevating it. Adapting to his partial blindness, he steadily lowered his scores, though his putting was erratic. The blindness in his left eye was distorting his depth perception. One day, in a fit of pique, he hurled his collection of putters off the Forth Rail Bridge into the firth below. It was these all-too frequent episodes of balky putting that would one day prompt him to coin the phrase “the yips.”

Despite his weakness on the greens, Armour began making his presence felt in tournaments, finishing runner-up in the 1919 Irish Amateur at Royal Portrush. He really raised eyebrows when he won the French Amateur in July 1920. Soon afterward, Armour sailed to New York, looking to test his game against America’s best. While aboard ship he met Walter Hagen, the game’s top professional golfer. The two men found they had much in common: Both enjoyed parties, the company of attractive women, and the consumption of copious amounts of alcohol. As author Mark Frost wrote in The Grand Slam: Bobby Jones, America, and the Story of Golf, the young Scot had a capacity for liquor surpassing his older friend. “Whereas ‘The Haig’ often watered down drinks to polish his reputation as a boozer,” wrote Frost, “Armour’s glass was never half-empty.”

Hagen took the young man under his wing, setting up an exhibition match for the visiting amateur’s American debut. On July 25 the fellow bon vivants squared off against Jim Barnes and Alex Smith in New London, Connecticut. The Armour-Hagen team lost the match 1-down, but The New York Times reported that Armour’s “long driving surprised the gallery,” and that his mashie play “stamped him as a golfer who will be hard to beat.”

In early August 1920, Armour entered the U.S. Open at Inverness Country Club, in Toledo, Ohio, finishing 48th, 22 strokes behind winner Ted Ray. But those who assumed the hype regarding this Scottish upstart had been overblown were in for a surprise two weeks later at the Canadian Open. Playing brilliantly throughout, Armour finished the championship in a three-way tie at the top with Charles Murray and J. Douglas Edgar, eventually losing the playoff to Edgar. The Scot followed that promising finish with another, reaching the quarterfinals of the U.S. Amateur at Engineers Country Club in Roslyn, New York.

While stateside, Armour found time for other pursuits. An October 29, 1920, New York Times article reported that the golfer had wed 26-year-old Consuelo Carreras de Arocena the previous day. A son, Thomas Dickson Armour Jr., would be born to the couple a year later.

Though Armour had played creditably that summer, he had yet to achieve a victory on U.S. soil. That changed in November after he arrived in Pinehurst to compete in the resort’s inaugural Fall Amateur-Professional Best Ball Tournament on course No. 2. The event attracted many leading players, including Gene Sarazen, the aforementioned Douglas Edgar, and Leo Diegel, later a two-time PGA champion.

Already recognized as a tournament hotbed, the Pinehurst resort successfully lured top players for tournaments on their way south for the winter and then again on their way northward in the spring. March and April were the months when the United North and South Amateur championship and the North and South Open were held. The tournaments attracted resort visitors looking to spot their favorites both on and off the course. What could be more appealing to a devout golf fan than encountering the legendary Walter Hagen in The Carolina Hotel bar?

Pinehurst appealed to Armour as well. Partnering with Diegel, the two ham-and-egged their way to the Amateur-Professional title, posting a four-round best ball score of 275. The win provided the Scot a measure of revenge against Edgar, whose team finished runner-up. The euphoric Armour extended his stay, competing in the resort’s match play Fall Tournament. He reached the quarterfinals before bowing to Frances Ouimet. After that, Armour and his bride sailed home to Great Britain.

Back in Scotland, Armour continued to polish his game in amateur tournaments. In May 1921, he joined a team of British amateur stars for a match against a formidable American team that included Bobby Jones, Chick Evans and Ouimet. The informal match, held at Royal Liverpool Golf Club and won by the U.S., drew over 10,000 spectators and sparked the institution of the Walker Cup matches the following year.

Having experienced the good life in America, Armour yearned to return. Following the 1921 slate of British golf championships, he was back in the U.S. competing in tournaments. In October he informed the press he intended to make America his permanent home. Armour’s brother Sandy and Braid Hills running mate Cruickshank also chose to emigrate. The New York Times observed, “The British golf world is faced with the odd spectacle of its previous defenders against American invasions being members of future attacking parties.”

Still an amateur, Armour looked to establish himself in America and, once again, Hagen came to the young man’s aid, making the connections that led to Armour being hired as the secretary of Westchester-Biltmore Country Club in Rye, New York. A sprawling complex, the club featured two golf courses, a polo field, racetrack and 20 tennis courts, built at a cost of $5 million.

Armour’s natural social skills made him ideal for the post. He deftly saw to the needs of the Biltmore’s guests and entertained them as well, regaling patrons with raucous stories evoking paroxysms of laughter. Byron Nelson considered Armour the most gifted storyteller he ever knew. “He could take the worst story you ever heard,” said Nelson, “and make it great.”

Armour’s job kept him busy during the warmer months, but when the weather turned chilly, he headed to Belleair, Florida, where he played numerous matches and tournaments against top players. Convinced he could hang with golf’s upper echelon, he turned professional in 1924. Soon after, Armour became the professional at Whitfield Estates Country Club, a Donald Ross-designed golf course (now Sara Bay Country Club) that was part of a Sarasota real estate project. Lifetime amateur Bobby Jones was also on-site, earning some extra dough peddling lots as the project’s assistant sales manager. Armour played golf daily, frequently in the company of either Jones or Hagen, who was affiliated with a nearby golf community.

In March 1925, Armour won the Florida West Coast Open, his first victory as a pro. With the North and South Open approaching, the triumph did not go unnoticed in the Sandhills. A piece in the Pinehurst Outlook reported that the word coming out of Florida was to “watch Tommy Armour!” The transplanted Scot played admirably in the North and South, finishing fourth.

Though Armour was rapidly progressing up the pecking order of top players, his share of tournament purses was never going to be enough to make a decent living. Even the game’s greatest supplemented their incomes by competing in exhibitions and securing club pro affiliations for both the summer and winter. Armour landed a premier summer gig as pro at Congressional Country Club in Bethesda, Maryland. Over the years, he would prove something of a vagabond in his northerly club employments: Medinah in Chicago, Tam-O-Shanter in Detroit, and Rockledge in Hartford would be featured among his other stints.

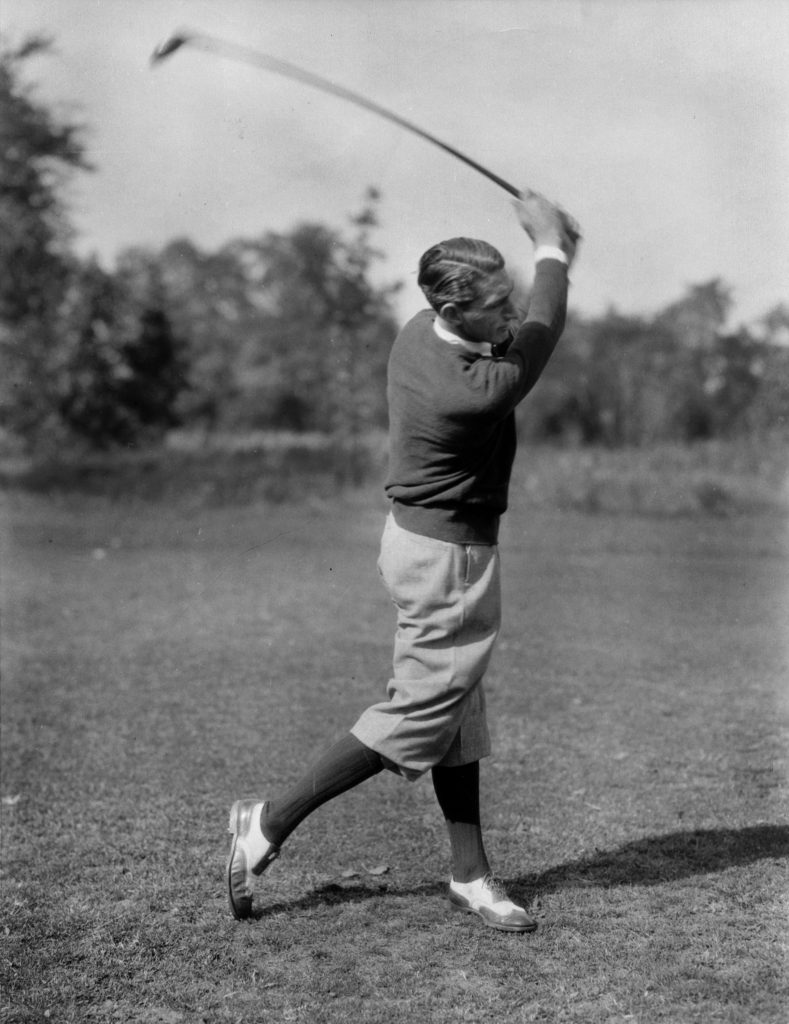

Armour’s primary goal, however, was to win tournaments. After two years adjusting to tour play, he skyrocketed to superstar status, winning five titles in 1927, including the U.S. Open held at America’s most demanding course, Oakmont Country Club. Trailing Harry Cooper by a shot as he arrived at the green of the championship’s final hole, Armour faced a birdie putt from 10 feet to force a playoff.

Bobby Jones, who was in the gallery, overheard two spectators debating whether any golfer would be able to successfully handle the pressure of such a critical moment. Jones calmly informed the bystanders that a man who had snapped the neck of a German tank commander with his bare hands was unlikely to be bothered by a 10-foot putt, regardless of its import.

Armour cooly drained it. In his 18-hole playoff victory over Cooper, Armour took just 22 putts over Oakmont’s diabolical greens. Perhaps he wasn’t such an awful putter after all.

The victory, coupled with his charismatic persona, thrust Armour into golf’s spotlight. Tall, dark, handsome and, like Hagen, impeccably attired, Armour, was a hit with the ladies, an attraction he did nothing to discourage. A penchant for heavy gambling, particularly on the course, also drew attention. Golf great Henry Cotton expressed uncertainty as to what Armour liked best, the golf or the betting. “He is not satisfied,” claimed Cotton, “unless he is wagering on every hole, every nine, each round, and if he can, on each shot.”

Augmenting Armour’s swagger was the occasional wearing of a patch over his left eye. He sported the best nickname on tour — The Black Scot — referring to the jet-black hue of his luxurious head of hair.

More victories followed. By the time Armour arrived at Fresh Meadows Country Club in Flushing, New York, for the 1930 PGA Championship, he had eight more tournament titles to his credit, including the prestigious Western Open. In his quarterfinal match at Fresh Meadows against Johnny Farrell, Armour found himself 5-down after six holes before rallying to win. Fighting his way to the championship’s final match, he took on Gene Sarazen in a nailbiter, beating “The Squire” on the 36th hole.

By 1930 Armour’s domestic life was in turmoil. In the course of his wanderings, he had met Estelle Andrews, the widow of an iron manufacturer. They started an affair, a fact unappreciated by Armour’s wife, Consuelo, who responded by initiating a series of lawsuits. Eventually, the differences were resolved; Armour got divorced, married Estelle, and adopted her two teenage sons, Ben and John. “Love and putting are mysteries for the philosopher to solve. Both are subjects beyond golfers,” said Armour.

In 1931, he won what, given his Scottish background, was his most meaningful title, the Open Championship at Carnoustie. An early finisher in his final round and sitting in a distant third place, Armour anxiously sipped whisky in the clubhouse while awaiting the two men ahead of him — Jose Jurado and Macdonald Smith — to complete their rounds. “I’ve never lived through such an hour before,” he told reporters. Jurado and Smith both collapsed, and Armour won the championship by one stroke, giving him a victory in all three of the major championships then available.

The rigors of travel and competition were beginning to take a toll on Armour, hastening the graying of his hair which, in turn, necessitated a nickname modification. Henceforth he was the Silver Scot.

Armour began slowing things down a bit by lengthening his sojourns in Pinehurst. His affection for the town would blossom into a full-blown love affair. His first extended visit occurred in the fall of 1932. After winning the resort’s Mid-South Best Ball Tournament with partner Al Watrous, the Armours, Tommy and Estelle, stayed over at The Carolina for several weeks’ rest before decamping to Boca Raton Hotel and Club, a winter head professional gig Armour would keep for the remainder of his life.

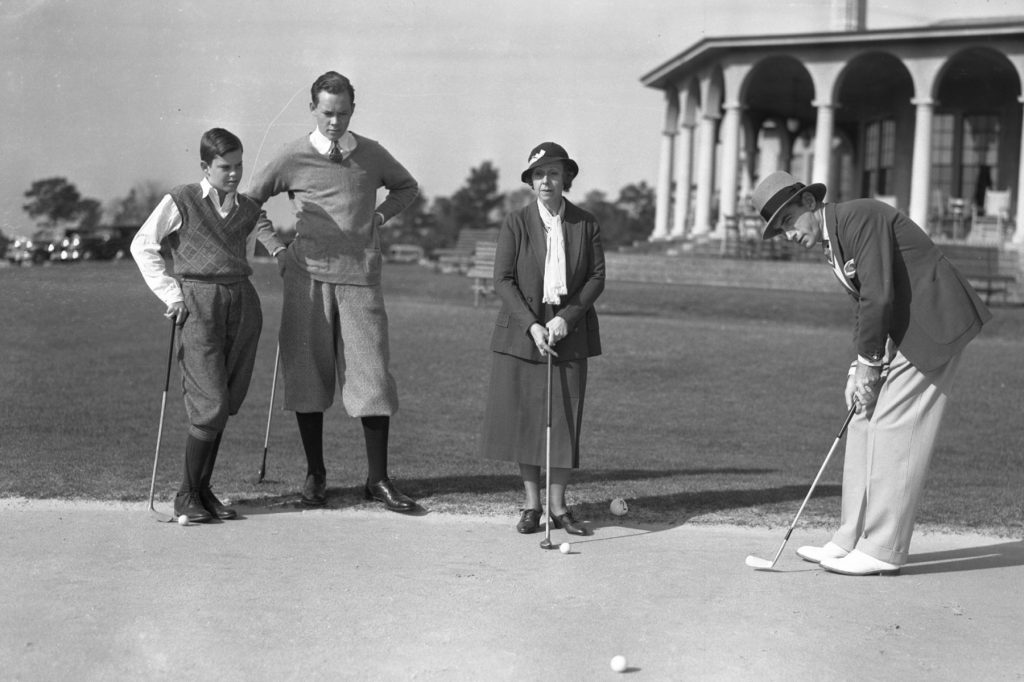

While in Pinehurst, the couple relaxed and socialized like any other guests of the resort. They brought sons Ben and John, both cadets at New York Military Academy, to Pinehurst for the holidays. The couple’s frequent movie attendance at the Pinehurst Theatre was dutifully reported in the Outlook. The Armours attended a dinner hosted by Southern Pines Country Club professional Emmett French, himself a three-time tour winner and runner-up in the 1922 PGA Championship. The Armours reciprocated, inviting the Frenches to dinner at The Carolina.

And, like most visitors to Pinehurst, Armour played loads of golf, generally with excellent players like French, Halbert Blue and poet Donald Parson, all reported in the Outlook. As the Armours prepared to depart Pinehurst in mid-January 1933, the paper recapped Tommy’s sensational scoring: “For a stretch of two weeks there was not one day in which Armour failed to equal or better the par of 71 for the No. 2 course. He had as low as 65 one day, this figure failing by one stroke to equal a round of his last month which tied the course mark.” And Armour revered No. 2, saying, “it is the kind of course that gets in the blood of an old trooper.”

In the spring of 1933, the Armours arrived early for the North and South and stayed two weeks after. Ben and John visited again, and Tommy played rounds with Pinehurst’s young phenom, George Dunlap Jr. Later that year, Dunlop won the U.S. Amateur, attributing significant credit for his victory to Armour. “Watching him play, of course, was a lesson in itself,” said Dunlop.

In December 1933, the Armour family once again celebrated the Christmas holidays in Pinehurst, and Armour was elected an associate member (later designated as an honorary member) of Pinehurst’s venerable golf society, the Tin Whistles. Returning in the fall of ’34, he paired with his boyhood friend Cruickshank to win the Mid-South Scotch Foursomes. After the victory Tommy and Estelle remained in Pinehurst, enjoying an array of social functions and attending the theatre, until the second week of January.

After 1935, Armour was competing only sparingly on tour. He was hired by MacGregor Golf in 1936 and, unwilling to simply sit back and endorse the company’s clubs, actively involved himself in their design. As a result, MacGregor became the industry-leading club manufacturer. “Tommy Armour” brand clubs are still made and marketed today.

Armour achieved fame as an instructor, despite delivering frequent tongue lashings to his pupils. An article by H.K. Wayne described his unique teaching methods: “His preferred style involved sitting in the shade in Boca Raton each winter or in Winged Foot each summer, with his trademark tray of gin, Bromo-Seltzers and shots of Scotch and passing judgment on his wealthy pupils, all of whom feared him.” Armour would subsequently author, with the assistance of golf writer Al Barkow, How to Play Your Best Golf All the Time, a bestseller, still in print.

Armour continued making pilgrimages to Pinehurst. The more time he spent in the Sandhills, the more he rhapsodized about how wonderful it was to be there. His fawning quotes were undoubtedly appreciated by the resort’s public relations department. “I’ve seen strangers, jaded and dull, come to Pinehurst, and after a few days be changed into entirely delightful fellows,” said Armour. Pinehurst’s practice ground elicited quotable praise. “Maniac Hill is to golf,” he asserted, “what Kitty Hawk is to flying.”

In yet another homage, he declared, “I can’t help it. Pinehurst gets me. From morning firing practice at Maniac Hill, to vespers at the movies, Pinehurst is the way I’d have things if it were left to me to remold this sorry scheme of things entirely. . . . It’s the last in the vanishing act of fine living.”

In a sense, Armour promotes Pinehurst even today. Exhibited in the resort clubhouse’s hallway of golf history is a rotating display that provides another Pinehurst tribute from the Silver Scot. It neatly combines in one statement his sentimentality and occasional brusqueness, reading, “The man who doesn’t feel continually stirred when he golfs at Pinehurst beneath those clear blue skies and with the pine fragrance in his nostrils is one who should be ruled out of golf for life.”

When Armour came to Pinehurst in November 1938 to play the resort’s two professional events — the Mid-South Professional Best Ball and the Mid-South Open — he was semi-retired from competition. His last individual tournament victory had taken place three years prior at the Miami Open. Inspired by his surroundings, the 42-year-old rekindled his old form. Not only did he and sidekick Cruickshank tie for the best score in the best ball, Armour won the individual title, too. It would be his 25th and last PGA Tour victory.

One of the few titles to elude Armour’s grasp was the North and South. This gnawed at him both because of his love of the venue and because of the tournament’s prestige. Runner-up twice, Armour dwelled on his near misses, ruminating that “there are five traps on this course (No. 2) that have cost me the North and South five times.” He continued competing in it long past his competitive heyday. He even had a shot at victory after the tournament’s first two rounds in 1948 when his 143 total left him just three strokes out of the lead, but an 81 in round three ruined the aging veteran’s bid.

In 1951, Armour attended Pinehurst’s lone Ryder Cup. It turned into a delightful reunion for the 54-year-old. Longtime friends Hagen, Sarazen and Cruickshank were also on hand, and Armour delightedly joked and hobnobbed with the old stalwarts. When Hagen held a driver for a photo op with his fellow legends, Armour, ever the scolding instructor, pointed out, “You never gripped a club that way in your life!”

The North and South immediately followed the Ryder Cup, and Armour gave it one final try, missing the cut by two shots. The ’51 event also marked the end of the line for the North and South itself — the result of a brouhaha between the PGA tour and Pinehurst resort owner Richard Tufts. He had resisted efforts by the tour to have the amount of prize money bumped from $7,500 to $10,000 — the tour minimum. In response, several American Ryder Cuppers left Pinehurst following the matches, effectively boycotting Tufts’ event. Only one team member, Henry Ransom, completed all 72 holes. Reciprocating the hard feelings, the miffed Tufts terminated the North and South after a 50-year run.

In Armour’s later years, he kept on playing, teaching, storytelling, gin playing, gambling and cocktailing. In a 1978 Sports Illustrated article, Scottish writer and an excellent golfer in his own right John Gonella recounted an experience 30 years before when Armour hosted him at the Boca Raton Hotel. The writer was amazed at how the hotel’s management cheerily indulged Tommy’s every whim, happily picking up a multitude of expensive tabs for him and his parade of guests. After the young Gonella, short on funds at the time, and Armour teamed up to win a golf bet, Armour generously shared the winnings with his broke writer friend.

At lunch in the grillroom afterward, Armour asked Gonella if he would like to meet Walter Hagen. When the reply was affirmative, Armour called to the bartender and commanded, “Get me Hagen on the phone: Detroit Athletic Club, last stool at the left end of the bar. And bring us a phone!” According to Gonella, Tommy had Walter on the line two minutes later, and greeted The Haig with, “Hello, you old has-been. There’s a friend of mine here from Scotland I want you to meet.”

Armour, a 1976 inductee into the World Golf Hall of Fame, passed away in 1968 at the age of 71. Shortly before his death, he shared a visit with his 8-year-old grandson, Thomas Dickson Armour III. The fruit would not fall far from the tree (though perhaps skipping a generation). Tommy III became a fine player himself, winning twice on the PGA Tour and setting a 72-hole scoring record. Now semi-retired from competitive play, Tommy III resides in Las Vegas, where his reputation for living the high life tends to overshadow his golf achievements. He even has his own nickname, “Mr. Fabulous.”

Given his tender years at the time of the childhood visit, it’s understandable Tommy III doesn’t remember much about his grandfather. But it did stick in his memory that the elder Armour was very handsome and, even in the late stage of life, exceptionally strong. Those hands never weakened.