Bravery, blunders, and bloodshed at Monroe’s Crossroads

By Bill Case

Art by Martin Pate and the Fort Bragg Cultural Resource Management Program

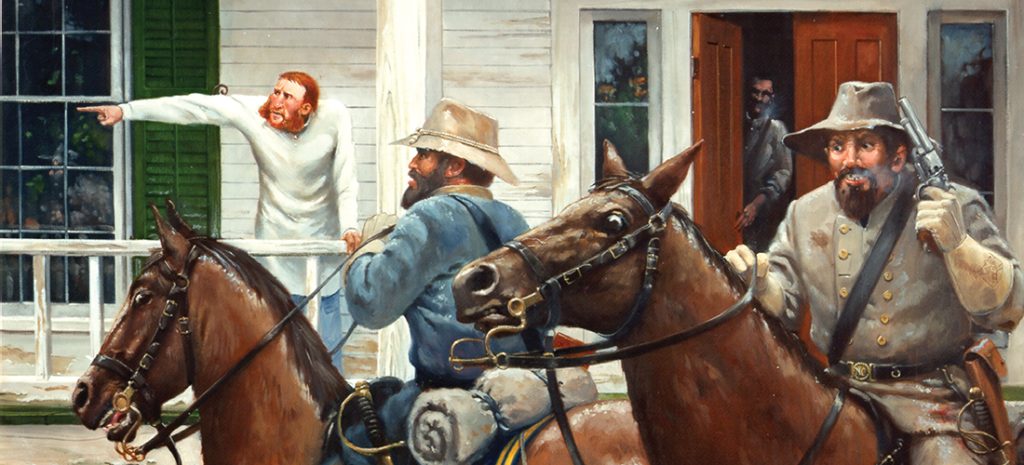

Gen. Kilpatrick misdirects Confederate cavalry.

The arrival of dawn on March 10, 1865, became an unwelcome wake-up call for Lt. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick. Stirred from his bed by the sound of thundering hoofbeats, the Union cavalry leader, clad only in his nightshirt and drawers, rushed to the front porch of Charles Monroe’s farmhouse, 8 miles east of present-day Southern Pines on what is now the Fort Bragg — soon to be Fort Liberty — Army reservation. Having commandeered the house for his temporary headquarters, what Kilpatrick saw shocked him. Hordes of Confederate cavalry were swooping down on his sleeping encampment, slashing with sabers and firing point-blank at bleary-eyed Union troops. Thus began “The Battle of Monroe’s Crossroads.”

“In less than a minute,” Kilpatrick would later report, the Confederate horsemen “had driven back my people, and taken possession of my headquarters, captured the artillery (two cannons), and the whole command was flying before the most formidable cavalry charge I ever have witnessed.” The general’s immediate thought was, “Here is four years’ hard fighting for a major general’s commission gone up with an infernal surprise.”

Tagged with the scathing moniker “Kill-cavalry” because of a history of unnecessarily putting his troops in harm’s way, the general’s improvident failure to set pickets and safeguard his headquarters was an especially egregious omission and could well torpedo his military career. It enabled Confederate cavalry, led by Gen. Wade Hampton and subordinate generals Joseph Wheeler and Matthew Butler, to ride undetected and unopposed straight into the Union camp.

Kilpatrick’s attention may have been distracted by the presence of a woman. Depending on the historian consulted, the woman was either the beautiful Marie Boozer or a plain Yankee schoolmarm named Alice. In either case, the woman was believed to be sharing Kilpatrick’s bed at the farmhouse. The general, it seems, was caught with his pants down.

One objective of the Confederate attack was to capture Kilpatrick. A cadre of Georgia cavalry, finding a man still in his bedclothes standing on the porch of Monroe’s farmhouse, demanded to know where the Union general was. It was Kilpatrick, of course, and he quickly pointed to a figure riding off in the distance, “There he goes on that black horse!” exclaimed the general.

The Georgians turned and rode off in pursuit. Leaving either Alice or Marie behind, Kilpatrick scrambled off the porch, climbed aboard a stray horse — not his prized Arabian stallion “Spot” — and promptly hightailed it into the woods, where many of his cavalrymen had retreated. To this day, the general’s flight is disparagingly labeled “Kilpatrick’s Shirt-Tail Skedaddle.”

The Confederates had good reason to target Kilpatrick, whom they had come to despise for his part in the Union Army’s devastating blitz of the South. Six months earlier, on Sept. 2, 1864, Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s 60,000 Union soldiers had occupied and burned the city of Atlanta when depleted Confederate forces — commanded initially by Gen. Joseph Johnston, followed by Gen. John Bell Hood — were unable to halt the Union troops’ advance. In response, the president of the Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, installed Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard as the commander of the newly formed Department of the West, comprised of five Southern states that included Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina.

Hampton’s scouts discover tracks to Kilpatrick’s encampment.

But with fewer than 30,000 soldiers scattered over several states, Beauregard was equally powerless to prevent Sherman’s next move, his “March to the Sea,” made during November and December, 1864. During a five-week trek from Atlanta to Savannah, Union soldiers laid waste to military installations, factories and railroads in an effort to choke off the Confederacy’s economic lifeblood. Leading the Union cavalry was Kilpatrick, whose zeal for destroying enemy property made him, according to Sherman, “just that sort of man to command my cavalry on this expedition.” The general, aware of Kilpatrick’s faults, also referred to him as “a damn fool.”

After the Union troops reached Savannah on Dec. 21, 1864, commander-in-chief Gen. Ulysses S. Grant considered having Sherman move his army north by sea to Virginia, where the two generals would combine their forces to finish off Lee in Petersburg. But Sherman had a different plan in mind. He proposed marching his men north through the Carolinas to link up with Grant. Sherman persuaded his commanding general that the maneuver would devastate resistance in both states. Grant agreed, ordering him to “make your preparations to start on your expedition without delay . . . break up the railroads in South and North Carolina, and join the armies operating against Richmond as soon as you can.”

The bulk of Sherman’s army began exiting Savannah at the end of January 1865, soon entering South Carolina. Sherman was not inclined to treat the first state to secede gently. “The whole army is burning with an insatiable desire to wreck vengeance upon South Carolina,” he would write. “I almost tremble at her fate, but feel that she deserves all that seems in store for her.”

Sherman and other Union commanders have been criticized for rebuffing the pleas of numerous former slaves seeking the army’s protection during its Southern campaign. Hungry and fearful of being recaptured (or worse) by their former masters, the liberated, but nonetheless desperate, slaves attempted to attach themselves to the Union force. But the army mostly stiff-armed them on the grounds that the Blacks need for food and supplies would drain available resources and slow the march. In one measure of retribution against the slaveholders in the Deep South, Sherman issued an edict setting aside 400,000 acres of coastal areas in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida for freed slaves, an order later reversed by Andrew Johnson.

Gen. Wade Hampton, commanding the cavalry supporting Lee’s army in Virginia, could not bear the thought of being absent from the upcoming fight in his home state of South Carolina. Hampton, deemed by Confederate Gen. James Longstreet the “greatest cavalry leader of our or any age,” was granted leave by Lee to return to the state along with Gen. Matthew Butler and the latter’s cavalry division.

Hampton also convinced Lee to place him in command of the Confederate cavalry in the area. This created friction between Hampton and “Fighting Joe” Wheeler, who had days before led his men to victory over Kilpatrick’s cavalry at Aiken, South Carolina. Hampton and Wheeler managed to put aside any ill feelings and established an effective working relationship, later evidenced at Monroe’s Crossroads.

Readied for the dawn attack.

In the early stages of the Carolinas Campaign, Sherman kept Beauregard and Hampton guessing where his army was heading. To confuse them, he ordered the Union left wing westward toward Augusta, Georgia, while directing his right wing to feint in the direction of Charleston. Then Sherman brought the troops back together to make a beeline to Columbia, South Carolina. The state capital was lightly defended, and Hampton had no choice but to order his troops to evacuate. On Feb. 17, Sherman’s unopposed army occupied the city.

A massive fire broke out that consumed most of Columbia’s buildings. Arguments raged regarding who caused the conflagration. Did the responsibility lie with fleeing Confederates who allegedly set fire to a storehouse of cotton bales? Or was the fire ignited by vengeful Union soldiers? Sherman pointed the finger at Hampton, who pointed his own, presumably uplifted, digit back at “Uncle Billy.”

The two adversaries exchanged hostile messages regarding the fate of Union foragers, a number of whom Sherman claimed had been murdered by Confederate soldiers after capture. He notified Hampton of his intent to respond in kind by executing a like number of Confederate prisoners. Hampton emphatically denied Sherman’s charge and upped the ante, promising that “for every soldier of mine ‘murdered’ by you, I shall have executed at once two of yours, giving in all cases preference to any officers who may be in my hands.” Both generals got each other’s message, and no further executions of foragers or other captives occurred.

The Columbia debacle accentuated fears of Confederacy higher-ups that annihilation of their cause was at hand. On Feb. 22, a desperate Gen. Lee relieved the beleaguered Beauregard and brought Gen. Johnston back to command the Department of the West. Johnston was under no illusion he could reverse the course of the war. In his memoirs, the general acknowledged that his primary object was “to obtain fair terms of peace; for the southern cause must have appeared hopeless then to all intelligent and dispassionate southern men.”

Given the Confederate Army’s vanishing manpower, achieving any terms beyond the CSA’s unconditional surrender would be a daunting undertaking. At the time Sherman crossed into North Carolina (March 3, 1865), the only Confederate infantry in Sherman’s immediate vicinity was Gen. William Hardee’s corps of 6,000 soldiers. Outnumbered 10 to 1, the most Hardee could be expected to do was shadow Sherman’s advance.

A more workable short term option for Johnston was employing his Hampton-led cavalry to dog the Federals with hit-and-run raids. As author Eric J. Wittenberg explained in his book, The Battle of Monroe’s Crossroads, the 4,000 horse soldiers of Hampton, Wheeler and Butler resisted Sherman by “hovering around the edges of the Federal column like a swarm of angry hornets ready to exact a heavy toll whenever an opportunity presented itself.”

Another dilemma for Johnston was not knowing where the Union Army would head after sacking Columbia. Sherman’s actual next destination was Fayetteville. Once there, his army could obtain supplies transported by steamboats sailing up the Cape Fear River from the coastal port of Wilmington, the latter having fallen into Federal hands in February. After destroying the arsenal at Fayetteville, Sherman intended to cross the Cape Fear and move his army to Goldsboro, North Carolina, where it would link up with Gen. John Schofield’s corps of 30,000 soldiers. Their combined force of 90,000 soldiers would then join Grant in Virginia for the final push against Lee.

The confederate charge at Monroe’s Crossroads.

A critical element of Sherman’s strategy was getting to Fayetteville before Hardee. Doing so would enable him to block or destroy the bridges across the river. Either measure would prevent Hardee’s corps and Confederate cavalry units from joining up with Braxton Bragg’s corps and other remnants of Joe Johnston’s dwindling forces.

Johnston’s strategy was basically a mirror image of Sherman’s. If Hardee reached Fayetteville ahead of the Federals, he was directed to cross the river and blow up the bridges behind him. This would frustrate, or at least delay, Sherman’s own crossing. Meanwhile, Hampton’s cavalry would hound the Union Army, inhibiting its progress.

The race would entail both Federal and Confederate forces passing through Moore County. Exhausted forces on both sides shivered as incessant, near-freezing rains with accompanying spring floods hampered their movements. Moore County was a quagmire! Kilpatrick described the grueling conditions as “the most horrible roads, swamps, and swollen streams.”

When Kilpatrick entered the county on March 7, he was several miles ahead of Sherman, who sent a message directing his cavalry leader “to deal as moderately by the North Carolinians as possible.” The general also counseled Kilpatrick to “keep up the seeming appearance of pushing after Hardee, but really keep your command well in hand, and the horses and men in the best possible order as to food and forage.”

As Kilpatrick consumed a meal of boiled sweet potatoes at the farm of Evander McLeod (near present day Pinebluff) on the evening of March 8, it had become abundantly clear that the West Point grad would be hard-pressed to avoid hostilities with the Confederate cavalry buzzing around him. Wade Hampton’s men had left McLeod’s farmstead just hours before.

The impending danger was compounded by Kilpatrick’s decision to send out scouting parties in search of alternative routes to avoid his troops’ overtaxing of the roads. As Wittenberg writes, “The farther his (4,000) men spread out . . . the more the Federals risked attack by marauding Confederate cavalrymen hovering just beyond the fringes of Kilpatrick’s column.”

At times, Kilpatrick seemed oblivious to these concerns. During the following day’s march, a Confederate prisoner, while walking alongside the carriage of “Little Kil” —he stood 5 feet, 3 inches in height — observed the general laying his head in Alice’s (or Marie’s?) lap and dangling his feet out the carriage window.

Meanwhile, at about 2 p.m. on March 9, Kilpatrick’s Third Brigade, headed by Col. George Spencer, arrived at the small hamlet of Solemn Grove, comprised of Buchan’s post office, a store, a mill and a few houses, including that of Malcolm Blue. Spencer was followed by William Way’s dismounted Fourth Brigade accompanied by 150 Confederate prisoners. Little Kil’s first and second cavalry brigades, commanded by Col. Thomas Jordan and Brig. Gen. Smith Atkins, respectively, were farther behind.

Kilpatrick’s men counterattack.

Upon receiving intelligence that Hampton’s cavalry was heading for Fayetteville, Kilpatrick concocted a scheme. He would seek to intercept the Confederate horsemen and prevent their planned rendezvous with Hardee, now certain to beat the Federals to the Cape Fear. The gambit meant blocking three different roads that Hampton and his subordinates, Wheeler and Butler, might potentially use: Morganton Road, Chicken Road to the south, and Yadkin Road to the north. Kilpatrick ordered Spencer to block the Yadkin Road. Another sortie was assigned to Way’s 400-man dismounted brigade. It marched farther east to block Morganton Road. Atkins, following behind as a rear guard, was urged to close up his brigade’s distance from Spencer and Way. The three brigades were ordered to establish camp at Monroe’s Crossroads, though circumstances would prevent Atkins from arriving there until well after hostilities commenced the following morning.

Way’s brigade reached Monroe’s Crossroads at 9 p.m. and set up camp adjacent to Charles Monroe’s farmhouse at the intersection of Morganton and Blue’s Rosin roads. Spencer’s brigade arrived soon thereafter, setting up its camp on a plateau that sloped toward a dismal swamp. Meanwhile, Jordan’s First Brigade, 3 miles distant, blocked Chicken Road. Kilpatrick’s separation of his brigades carried risk as each unit was rendered more vulnerable to attack. At the time Kilpatrick’s bugler sounded “taps” the night of March 9, there were around 1,400 Union soldiers at Monroe’s Crossroads, but had Kilpatrick played into the enemy’s hands by dividing his brigades?

Meanwhile, Confederate Gen. Butler had an unexpected prize fall into his lap. While patrolling with his division on the evening of March 9, he detected the sound of approaching hoofbeats. Butler called out, “Who goes there?”

“Fifth Kentucky,” came the response. Butler knew the 5th was a Federal unit.

He beckoned the soldiers to come forward and, without firing a shot, Butler promptly disarmed and took into custody 28 unsuspecting Kentuckians. The captives were all members of Kilpatrick’s headquarters escort company. It appeared Kilpatrick had been nearby and had narrowly avoided his own capture, hightailing it to Charles Monroe’s farmhouse. Sharing the residence with Little Kil and Alice (or Marie) were brigade leaders Spencer and Way, who bunked upstairs. Despite his close call and the distressing disappearance of the escort company, Kilpatrick inexplicably neglected to post any guards.

As a gleeful Butler regaled Hampton with the tale of his evening’s adventure, a scout rushed up to inform the generals that the tracking of hoofprints had led him to discover the union cavalry’s encampment at Monroe’s Crossroads. It appeared unguarded to the scout. Hampton, after conferring with Wheeler and Butler, sensed an opportunity to catch Kilpatrick napping (or otherwise occupied) and ordered a dawn attack.

Wheeler thought the attack would be more effective if made on foot. But Hampton overruled him. “General Wheeler,” said Hampton, “as a cavalryman I prefer making this capture mounted.” And so it was that at 5:20 a.m., the oft-wounded Hampton, astride his horse, led his cavalry’s ferocious charge into the Union camp. The 49-year-old master horseman reputedly dispatched three Union soldiers in the process.

It seemed certain Hampton was on the threshold of a glorious victory — one that could demonstrate to all that the war was not yet over. But the unforced errors were not the sole province of Kilpatrick. Several columns led by Wheeler were supposed to attack through an area that was marshy and full of thick vegetation. Wheeler thought the terrain would pose no hindrance, but he was wrong. Approximately half of Wheeler’s troops failed to make it through the muck and were late to the battlefield.

The attack caused the Union soldiers guarding the 120 Confederate prisoners to flee to the woods. Suddenly freed, the now ex-prisoners ran headlong and “frantic with joy” toward their liberators. At first, the cavalrymen thought the men sprinting toward them were retreating soldiers whose forward charge had been repulsed. The resulting confusion caused a temporary blunting of the Confederate assault. Furthermore, one of Butler’s brigades did not take part in the attack as it was ordered to escort the elated, but famished, former captives to the rear.

The newly liberated soldiers weren’t the only hungry ones. The Confederate cavalry soldiers also craved food. Many availed themselves of the opportunity to poke through the Union camp to find and consume whatever edibles they could lay their hands on. They looted belongings, scavenging shoes, blankets, saddles and mounts. The breakdown in discipline stemmed the momentum of Hampton’s onslaught and provided the Union cavalry breathing space to reform and rally. Local Civil War buff Jim Jones believes that the cavalrymen’s attention to the needs and whereabouts of their horses following the initial rush may also have added a distraction that would have been avoided had the charge occurred dismounted.

Hampton made another decision he would regret by not searching the farmhouse. Unknown to the general, Union brigade leaders Spencer and Way were still inside, hidden upstairs. Playacting by Kilpatrick’s paramour prevented the officers’ capture. Adopting the airs of a Southern belle, Alice (or Marie) greeted Hampton at the porch and assured him there were no Union officers inside her home. The chivalrous Hampton, not wanting to further trouble such a fine lady, posted a guard to keep rebel soldiers out of her hair, then bid the woman adieu. Spencer and Way remained grounded in the bedroom until the battle’s conclusion.

Lt. Stetson fires away.

Given the disarrayed and bedraggled appearance of Kilpatrick’s cavalry, it seemed next to impossible they could mount any sort of counterattack. Though they were chilled to the bone and nearly naked, most of Kilpatrick’s men had the presence of mind to grab their guns and ammo before fleeing from the camp. Jones points out that the veterans in Sherman’s army were as battletested as any in the war. “They bent at times but never broke,” says Jones.

According to Ohio horse soldier T.W. Fanning, Little Kil “cobbled together enough men to order an advance.” Then at his command, the horse soldiers “moved up the ridge, firing as they moved.” According to Fanning, the men “with one wild shout, swept down upon the rebels, who were swarming around the captured artillery and Kilpatrick’s former headquarters.” Adding impetus to Kilpatrick’s thrust were Capt. Theodore Northrup and his company of Union scouts. They had rushed to Monroe’s Crossroads upon learning of Kilpatrick’s plight.

Engaged as they were in premature celebration, it was Hampton’s cavalry now caught flatfooted. In the fog of the renewed gunfire, Lt. Ebenezer Stetson, who had been hiding from the Confederates under the farmhouse since the initial attack, surreptitiously crept to one of the cannons just 20 steps away. He loaded it with canister and fired away at the startled Confederates. Several of Hampton’s men were killed instantly. A second artillerist, believed to be Sgt. John Swartz, rushed to the second cannon and fired it to like effect. Together, they were able to inflict considerable damage until the guns were recaptured by Gen. Wheeler, largely through the ultimately fatal charge of Capt. Moses Humphrey. Swartz also died from wounds suffered in the battle.

Gen. Wheeler suddenly made his presence felt, charging into the camp and, according to a Georgian horseman, “killed several Yankees in close encounter.” He and Butler made repeated efforts to drive Kilpatrick’s men back toward the swamp, but they were met with withering gunfire courtesy of the Spencer seven-shot repeating carbines carried by an Ohio unit in the Union cavalry. Southern casualties were exacerbated because Wheeler’s and Butler’s men were packed close together due to the vagaries of the landscape. A disconsolate Butler reported that the carbines “made it so hot for the handful of us we had to retire. In fact, I lost 62 men (wounded and killed) there in about five minutes time.”

Coupled with his belief that Sherman’s infantry would soon be coming to Kilpatrick’s aid, Hampton ordered his cavalry to pull out and move on to Fayetteville. Both sides claimed victory at Monroe’s Crossroads. Kilpatrick boasted that he had driven the Confederate cavalry from the field. However, his negligent preparations would come under fire and Sherman never trusted him again. Hampton claimed his surprise attack freed prisoners and successfully stalled the Union cavalry, thus allowing Hardee to escape unscathed across the Cape Fear. But Hampton’s failure to capitalize on his initial advantage undercuts a claim of Confederate victory.

The precise number of battlefield deaths at Monroe’s Crossroads is unknown. The CSA wasn’t keeping records anymore, and Kilpatrick probably inflated the casualty figures. It would appear from accounts that a total of 150 dead is not far off. It was the last true cavalry engagement of the war.

As a result of Hardee’s escape, Joe Johnston was able to marshal 21,000 troops to battle Sherman at Bentonville on March 19. But Johnston was still outnumbered 3 to 1. As a result of heavy losses in this battle and the futility of further conflict, Johnston ultimately surrendered to Sherman. This followed Lee’s surrender to Grant at Appomattox Court House on April 9th.

Today the Monroe’s Crossroads battlefield can only be accessed by prior arrangement. Happily that’s not difficult. Jonathan Schleier, associated with Fort Bragg’s Cultural Resource Program, offered to provide a guided tour but because the penetrating boom of military munitions can still be felt there 157 years after Lt. Stetson fired a cannon at the site, Schleier had to find a date from Range Control when artillery operations would not be occurring in the area.

On a hot July morning, I met Schleier at Fort Bragg’s Ranger Station No. 2, located at the point where East Connecticut Avenue meets the post’s border. As the roadway continues into the reservation, it’s called Morganton Road, an unimproved pathway little changed since 1865. Riding in Schleier’s Ford F-150 we observed neither vehicles nor people en route to the remote battlefield. Schleier said that present day officers, as part of their training, walk the battlefield to study the tactics and maneuvers of the long-ago fight.

The Monroe farmhouse is gone, but an obelisk marks its location. The battlefield has a surprising number of monuments, all of them installed since 1990. There are combatants’ graves, including those specifically dedicated to unknown soldiers. One memorial is situated at the spot where Lt. Stetson unleashed his cannon. Schleier unfolded maps to aid in comprehending the movements of the antagonists. Walking the ridge-filled terrain and eyeing the steep incline down to the swamp it was possible to visualize the logistical challenges faced by both cavalries.

The old battlefield was eerily quiet. Not a sound to be heard. Just like it must have been before all hell broke loose at 5:20 a.m. on March 10, 1865.

To schedule a tour of the battlefield, call Jonathan Schleier at (910) 396-6680. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.

The first time

The first time