Discovering the basement treasures of Southern Pines

By Bill Case • Photographs by John Gessner

Around 1952, my mom found a tiny, tarnished silver coin in a dark, recessed area of our home’s basement floor. The ancient “half-dime” bore the date 1846.

It was hard to fathom how the 106-year-old piece had made it to our basement. Perhaps the coin dropped out of a worker’s pocket when the basement foundation was poured — a remote possibility, since few coins of that vintage would have been in circulation when our Hudson, Ohio, house was constructed in the 1920s. The half-dime puzzle was one our family never solved.

My mother gave me the mysterious half-dime after I began collecting coins as a pre-teen in 1960 but, over time, my interest in numismatics fell away, and I lost track of the coin. Perhaps it has been rediscovered by another mother in some other dark basement, launching a whole new family puzzle.

Thoughts of the half-dime returned when a Southern Pines restaurant server told me about her own belowground discovery at the Belvedere Hotel. She said the basement of the structure contained an iron-barred cell rumored to have once been a town jail facility. What other treasures might lurk in underground Southern Pines? Catacombs? The Phantom of the Opera’s dungeon? Or maybe just Al Capone’s vault?

With thoughts of Geraldo Rivera dancing in my head, I started my prospecting by following up on the server’s jail cell tip. According to a spokesman for the police department, there was no record of any jail having ever been located at the Belvedere Hotel. Undeterred, and with time on my hands until the afternoon four-ball, I contacted Melissa McPeake, a member of the family that owns the Belvedere building and several other area hotels. When asked about the supposed jail, Melissa responded, “Well, I’ve never heard that before. But there is an iron-bar door that provides an entry point to a room in the basement, and we’ve always wondered about it. Maybe it was a jail door. You’re welcome to check it out.” Ah-ha.

When Melissa and I descended the very steep basement steps (approximately the width of an iPhone 6), we came upon an iron-barred arched door in a remote area of the basement. The door looked like something out of an English castle dungeon in the Middle Ages. The only thing missing was Errol Flynn. But the absence of any actual jail cells cast considerable doubt on whether the forbidding door had ever served a role in incarcerating prisoners. It seemed unlikely that the space had ever been a black site interrogation room used by Andy Taylor and Barney Fife. Perhaps the iron bars guarded the hotel’s wine cellar, or served as a barrier protecting mail for the U.S. post office that had occupied a portion of the building long ago. But, no jail.

Tips regarding the whereabouts of buried treasure often lead to less than satisfying ends. But once on the hunt, you gotta keep looking. Nothing ventured, nothing gained. I was contemplating my next move when I spotted two men doing rehab work on the roof overhang of the old Carolina Theatre (most recently an antique store). I shouted up to inquire whether there was anything of note left in the venerable theatre’s basement. One of the workers, Bob Greenleaf, shook his head, but offered a helpful observation. “I’ve been in just about every basement in the downtown,” he said. “Right across the street in the Citizens Bank and Trust building, there’s a vault in the basement that wasn’t removed when they closed the bank.” Agile for a person with so much basement spelunking experience, Bob hopped off the roof to point the way.

In short order, I was across the tracks and inside the Pinehurst Resort store, appropriately called “The Vault.” On the first floor of the store is a 22-inch-thick concrete walled vaulted area that has been incorporated into the store’s sales area. But I was more interested in the basement. As Carl Reiner says in Ocean’s Eleven, “The house safe is for brandy and grandmother’s pearls.”

Store sales clerk Heather Shaffer confided that employees consider the belowground vault to be spooky. Ah-ha. “I’ll go down there and the vault door is closed,” she said. “Next time, it’s open even though no one has been downstairs since me.” Heather permitted me to take a look-see. This time, the formidable vault door was open. It appeared that the room it guarded could have been used to store safe deposit boxes. It seems these mammoth doors rarely get removed from a structure even after a change of occupants renders them superfluous. Such indestructible behemoths may outlast everything else in our civilization, like multi-ton cockroaches or Woody Allen’s Volkswagen in Sleeper. Or Woody Allen.

Undaunted, my next stop was The Country Bookshop, housed in the McBrayer Building. The store’s manager, Kimberly Daniels Taws, was unable to access the building’s basement, but she put me in touch with the man who could, Hans Antonsson, the building’s owner. Hans advised that there was an old treasure stored in the basement: a discarded cash register of indeterminate age left over from bygone days when the building housed either Pope’s department store, or, prior to the 1960s, Lee’s.

Iron bars, a bank vault and a cash register are all well and good, but I was hoping to discover treasures of a more unique nature. It was rumored that the basement wall of the Denker Dry Goods dress shop at 150 N.W. Broad contained a mural painted by Glen Rounds, the Southern Pines artist of national renown. The prospect of finding a “forgotten” work by the legendary Rounds was exhilarating.

Born in 1906 inside a sod house in the Badlands of South Dakota, Glen Rounds grew up on Western ranches. As an adult, he took various turns as a mule skinner, cowpoke and carnival medicine man. He developed a talent for drawing minimalist sketches of animals and depictions of humorous experiences from his cowboy life. Combining his artistic skill with innate storytelling ability, Rounds became a pre-eminent writer and illustrator of award-winning children’s books — 103 in all over a six-decade career. Recurring figures in his comical yarns included Paul Bunyan; Whitey, the pint-sized cowboy; Mr. Yowder, the sign painter; Beaver; and the “Blind Colt.”

After his military hitch was over in 1937, Rounds moved to Southern Pines and resided there until his death at age 96 in 2002. The town’s most illustrious man of the arts also ranked as one of its greatest characters. On his daily Broad Street treks, the peripatetic raconteur would buttonhole unsuspecting pedestrians and regale them with mesmerizing, albeit long-winded, fables. The bearded Rounds also delighted in sharing bits of his prolific artwork with friends and strangers, a trait described by writer Stephen E. Smith as follows: “Without warning . . . minimalist sketches of high-stepping hounds, plump wayward women, and skinny wranglers would appear in mailboxes or stuffed in door jambs. Many of them were signed: ‘The Little Fiery Gizzard Creek Land, Cattle & Hymn Book Co.’”

It was with high anticipation that I introduced myself to Denker’s owner, Kara Denker Hodges. I was gratified that Kara was able to corroborate the fact that the store’s basement wall did, indeed, contain a mural painting believed to be the work of Glen Rounds. “One problem,” she noted, “is that we have no electricity running in that area of the basement. It’s completely dark, so you’ll need a flashlight to see it.” After haplessly fiddling with the flashlight feature on my iPhone, the more tech-savvy Hodges took pity on me and activated her own.

Picking our way through cave-like darkness, Kara’s flashlight revealed a 25-foot-long mural of a train with its chugging locomotive and boxcars displayed in bright primary colors. The quirky, madcap choo-choo seemed the perfect artwork for a toy store. The mural certainly had the look of an illustration by “the last of the great ‘ring-tailed roarers’” but I had to be sure. Even archaeologists uncovering ancient hieroglyphics in the great pyramids of Egypt performed outside research. I needed to do the same.

Extensive review of The Pilot’s archives from 70 years ago, together with interviews of individuals who could recall that time, helped me piece together the train mural’s story. The structure housing Denker’s was once called the Hayes Building. Prior to June 1948, Claud L. Hayes and his wife, Deila, operated side-by-side retail establishments there. Deila, like Kara Hodges now, ran a dress shop while Claud was the proprietor of the Hayes Book Store. Indiana native Claud had sold books in the community since his arrival in 1895. The establishment was typically laden to the rafters with magazines, books and newspapers. The Pilot described the store as being filled with “cheerful clutter.”

It was just the sort of place that appealed to Rounds, who, comfortably ensconced in the shop’s friendly confines, dispensed to all comers his “special brand of philosophical banter defying classification.” The newspaper advised its readers, “You haven’t started the day off right until you’ve exchanged greetings with Glen at Hayes over the morning papers.”

Claud Hayes died in 1948, and Col. Wallace Simpson acquired the bookstore from Hayes’ estate in June of that year. Simpson envisioned a new concept for the basement section of the store, focusing on children’s books and toys. The colonel set about making the necessary renovations. A November 12, 1948 article in The Pilot revealed that an artistic work, painted by the store’s most omnipresent visitor, would be transforming the children’s section into something special.

“A privileged few who have seen the mural painted by Glen Rounds in Hayes’ new basement say that it is his masterpiece,” effused the newspaper. “Even if he had never written all those books and illustrated them . . . they say this one great work alone would make him immortal.”

While Rounds’ fanciful choo-choo hardly ranks with DaVinci’s The Last Supper, it stands as a fine example of his work and apparently jump-started a fervent desire on his part to paint far larger murals, including a dream of adorning an 800-foot space with, The Pilot suggested, “a serpent left over from his carnival posting days.”

Discovery of Rounds’ train painting spurred me to look for more hidden artwork. After getting wind of my search, local Realtor Chris Smithson put me on a promising path. He had heard that the unfrequented basement area under the west side of Ashten’s restaurant also contained unusual decorative work on its walls. Owner Ashley Van Camp confirmed the report.

“Oh, it’s unusual, all right. It’s of a foxhunt scene, and it’s unlike anything you’ve ever laid eyes on,” she said.

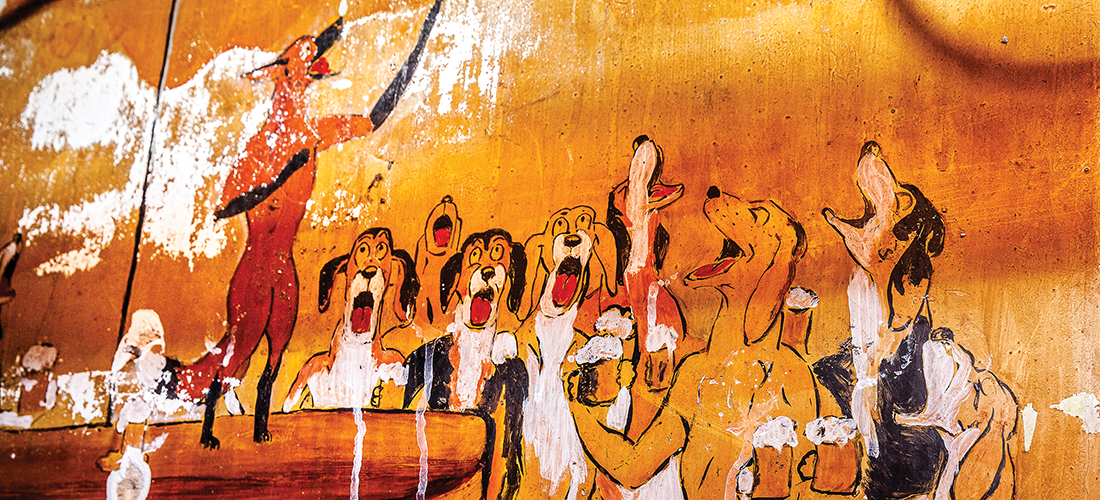

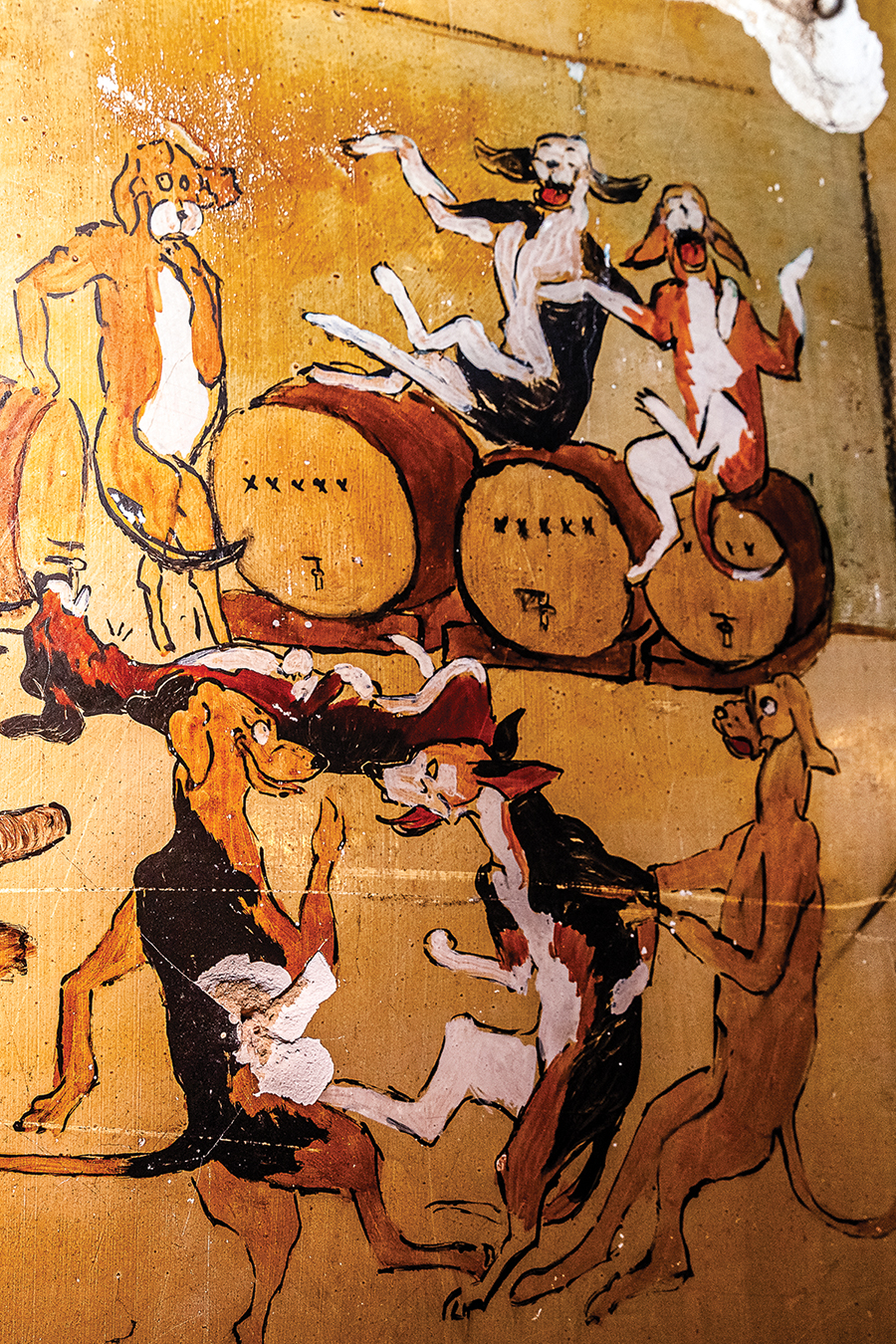

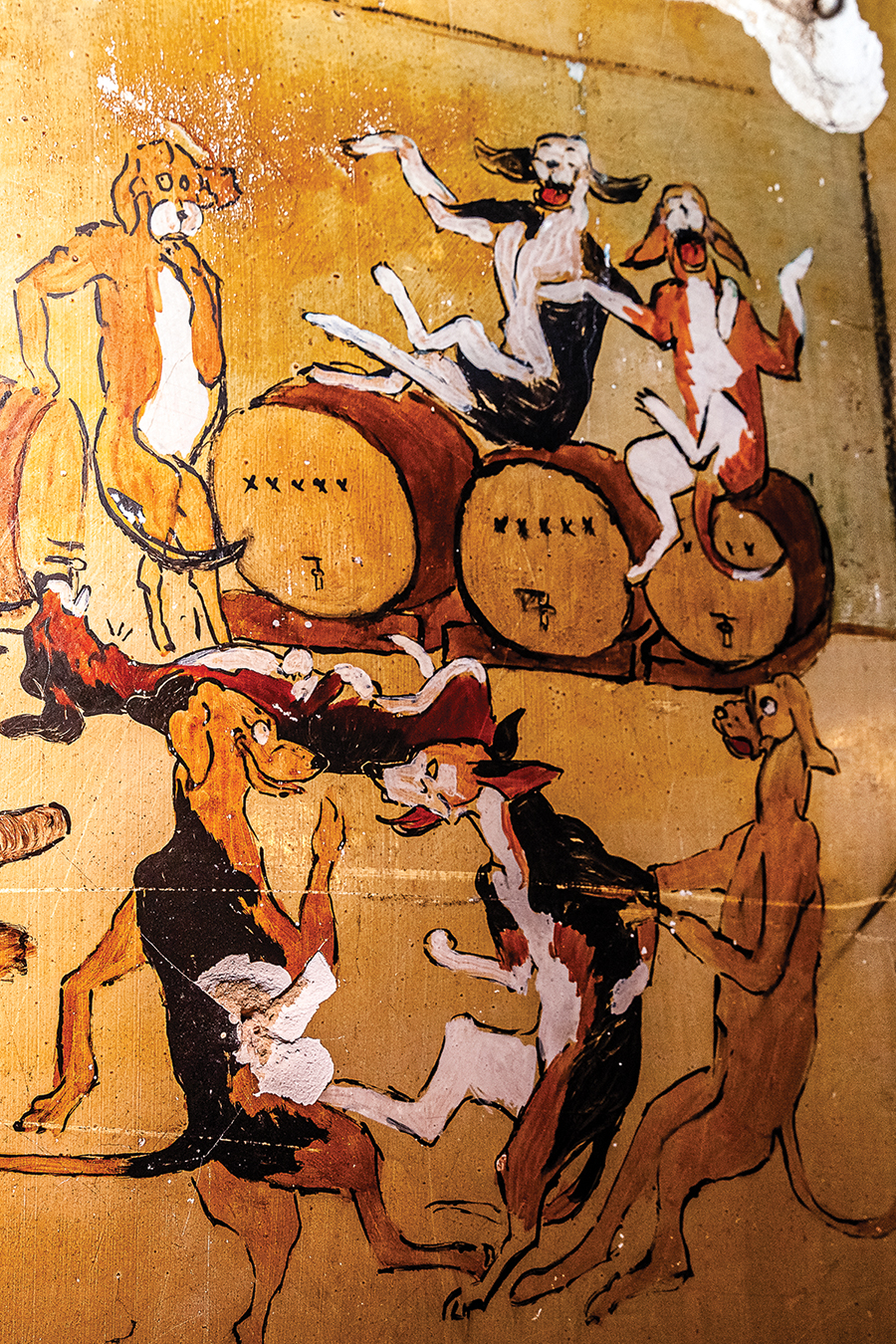

I joined Ashley and her husband, Charlie Coulter, behind Ashten’s and we negotiated the exceedingly narrow steps to the basement of the 118-year-old structure. Did all the early builders of Southern Pines have Lilliputian-sized feet? The area at the bottom of the stairs is not much more than 100 square feet but, just as Van Camp advertised, the mural displayed over three of its walls was anything but ordinary. In this depiction of a “running of the hounds,” the would-be quarry turns the tables on his pursuers. A grinning Mr. Fox, certain he faces no danger, speeds away atop a tricycle. Behind him, horses and riders topple like tenpins. An actual hole in the wall draws the attention of several hounds as a potential escape hatch for the fox. The overall effect is hilarious. The piece, terrifically illustrated in brown, black, and red tones, is an impressive and painstaking work of art.

I asked Ashley the standard reporter questions: “Who did it? When did the artist do it? Why was it done?” She pointed to a signature on one wall of the mural with the name “Mayo,” dated 1940. The name rang no bell with any of us. As to the circumstances that led to the painting, Ashley said that the basement is thought to have housed a small speakeasy during Prohibition, making the hounds of ’40 something of an homage to the dry days.

Ashley had long contemplated rehabilitating this forgotten area and incorporating it into the restaurant. The idea of installing a small, intimate bar and reprising the basement’s speakeasy legacy appealed to the owner. The work would require the eradication of a nest of dangling wires, restoration of faded portions of the mural, and the removal of three panels separating various portions of the paintings. The project was something of a pipe dream until COVID-19 hit and the resulting statewide restrictions changed everything for restaurant owners and their employees. Ashten’s chef, Matt Hannon, suddenly had time on his hands. Van Camp asked him to get started on the rehab.

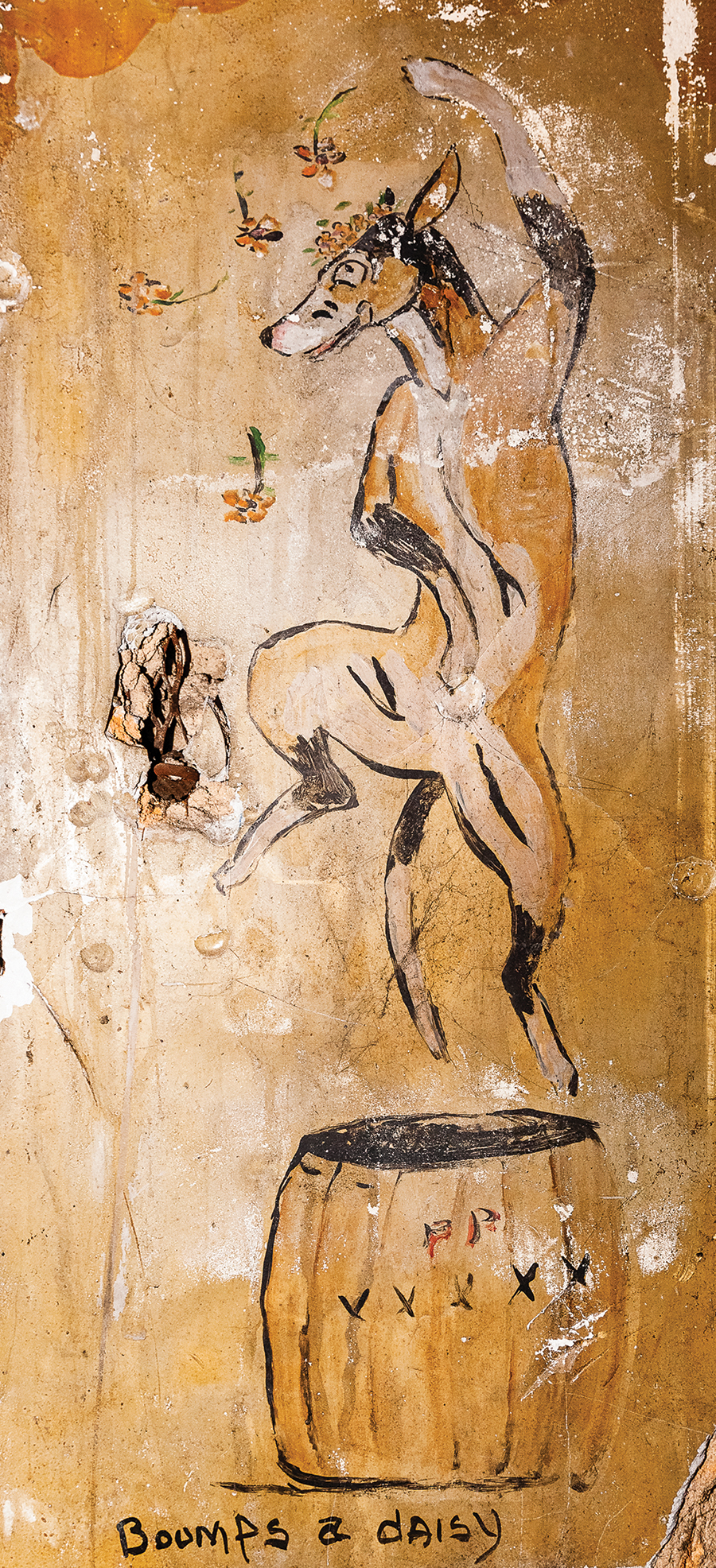

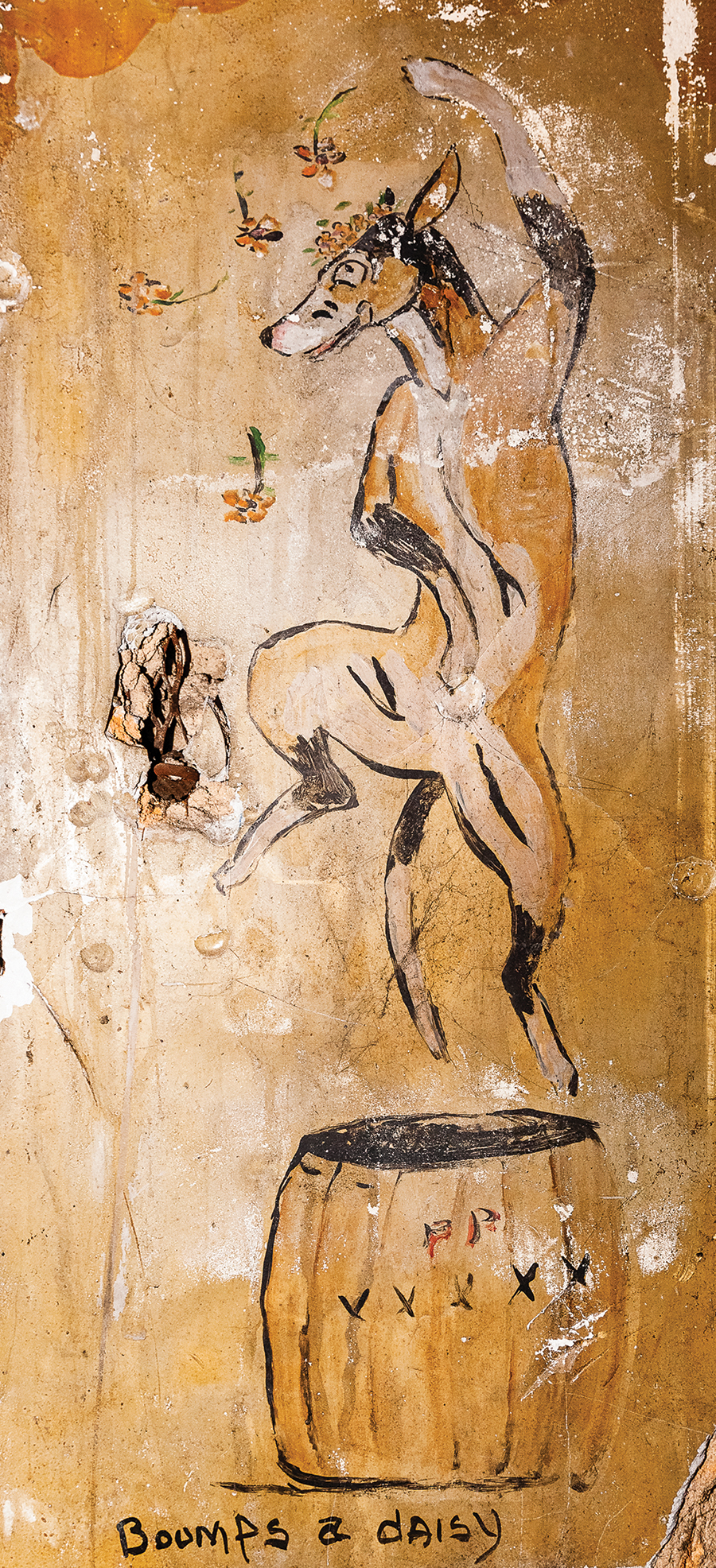

Suspecting that additional “Mayo” artwork might be hidden beneath the panels, Ashley had video equipment poised to record the unveiling. Voila! More comical illustrations appeared, all in excellent condition — inebriated hounds careening down a staircase; happy canines dancing and hoisting their glasses in toasts; and a hound prancing atop a whiskey keg with the words “Boomps a daisy” inscribed below. Mayo’s zany mural will eventually be on display for Ashten’s diners, perhaps in the “Boomps a daisy” room.

All that remained was to chase down and confirm the identity of the artist. Through her equestrian connections, Ashley learned that one Newton Mayo painted a portrait of the late Pappy Moss, benefactor of the Walthour-Moss Foundation and former master of the Moore County Hounds. Today, that painting hangs at the Full Cry horse farm of Mike and Irene Russell. According to a 2003 obituary in Virginia’s Richmond Times-Dispatch, Newton T. Mayo, who passed away at the age of 92, was “a retired horseman who earned a national reputation for his pastel portraits of Thoroughbreds and canines.” He raced Thoroughbreds up and down the East Coast and visited the Sandhills on several occasions. In its March 8, 1940 edition, The Pilot reported that Mrs. Newton T. Mayo won the fifth race of a steeplechase — approximately 1 mile on the flat — aboard Ever Ready.

While the middle of Mayo’s working life was devoted to training and racing horses, he was known for his artwork both as a young man (he would have been 29 when he painted the murals in Ashten’s basement) and when he returned to it in his later years. His commissions included equine paintings for President Ronald Reagan and a portrait of Barbara Bush’s springer spaniel. Displaying something of the same playful nature as his Ashten’s paintings, Mayo is quoted as saying that he preferred drawing pictures of animals “because they are less critical and ask for no flattery at all.”

And so, one thing leads to another. A half-dime to a haunted vault to Glen Rounds’ immortal choo-choo to a speakeasy fox and over-served hounds. Treasure, it seems, is in the flashlight of the beholder. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.