The most celebrated arrival was undoubtedly Flora MacDonald. She achieved everlasting fame after the Culloden debacle, when she aided Bonnie Prince Charlie’s escape to the Island of Skye by disguising him as an Irish spinning maid. She paid for her assistance to the Jacobite cause with imprisonment in the Tower of London for several months. In 1750, she married Allan MacDonald, ironically a captain in the British Army. They lived on Skye until emigrating to North Carolina in 1774.

The Highland Scots destined for North Carolina assumed they were leaving behind a civil war that had rendered their lives unbearably difficult. It must have been alarming to arrive here to find rebellion in their midst once again. They wanted no part of it. Aside from their irrevocable oaths to King George III, other practicalities mitigated against supporting the cause of independence. England had easily crushed the Jacobites at Culloden. What would prevent the greatest military power on Earth from quelling an American rebellion? There was commerce to consider too. Many of the Scots, like Kenneth Black, had become successful farmers. The longleaf pines on their estates produced naval stores of pitch and turpentine marketed to the mother country. And there was cotton. War would interrupt that trade. Why rock the boat?

Once the “Shot Heard Round the World” was fired in Lexington on April 19, 1775, war was suddenly at hand. One month later, patriots (also known then as Whigs) in the Charlotte area adopted the Mecklenburg Declaration, which is said to be the first formal action by any group of Americans to declare independence from Great Britain. When word reached Royal Gov. Josiah Martin that the Whigs’ Safety Committee in New Bern was poised to seize him, he fled the Royal Palace and took refuge in a British ship offshore. With astonishing alacrity, the Whigs orchestrated a takeover of the reins of government.

In August 1775, a convocation of Whigs was held at the “Hillsborough Provincial Congress.” This assembly took up the question of raising troops to defend the colony against an anticipated British invasion. Two regiments were authorized (known as the “Continental Line”) , but lack of funding meant that the majority of Patriot fighters during the war were militia members.

While those favoring independence in North Carolina were in the majority, the Highland Scots provided a formidable counterweight favoring allegiance to the king. They were joined by remnants of the Regulators movement. The Regulators were western North Carolina settlers who had rebelled against the fraudulent imposition of fees and taxes by conniving public officials. This brouhaha had led to the Battle of Alamance in 1771 — a devastating defeat for the Regulators. The movement collapsed, and its surviving members were forced to swear their own oaths of allegiance to the king.

In the early stages of the Revolution, the Whigs sought to lure the Highland Scots and Regulators (collectively referred to as “Tories”) to the revolutionary cause with various inducements. But when those offers were rejected, the Whigs resorted to coercion in the form of arrests, banishments, estate confiscations and tax penalties. Seeking to restore royal rule, the embattled Gov. Martin made his own overtures to recruit the Highlanders to join the Royal Highland Emigrant Regiment (“the Highland Regiment”), promising 200-acre grants to all who enlisted. Martin, not above threatening reprisals against recalcitrant Scots, proclaimed those refusing service risked having “their lives and properties to be forfeited.”

Martin’s recruitment efforts met with some success. On February 2, 1776, 1500 Highlanders and a smaller number of Regulators gathered at Cross Creek near Fayetteville to join the Highland Regiment led by Gen. Donald MacDonald. Flora MacDonald’s husband, Allan, served as an officer in the Regiment. Flora herself is said to have made a fiery oration urging valor in upcoming battles to her fellow Highlanders. The plan was to march the Highland Regiment to Wilmington to link up with British forces led by Gen. Lord Charles Cornwallis, who was scheduled to be arriving shortly by sea. But Patriots led by Col. James Moore and Richard Caswell rushed to block the Regiment at Moore’s Creek, eighteen miles north of Wilmington. Realizing that the Regiment would be crossing Moore’s Creek Bridge, Moore and Caswell removed most of the bridge’s planking, greased its support rails with tallow, and awaited the Regiment’s appearance. When the Highlanders arrived and attempted a charge across the bridge, they were welcomed with deadly cannon and rifle fire.

It was a rout. Fifty Scots perished on the bridge, and the majority of the Regiment was captured and imprisoned. Allan MacDonald was among them. Those that escaped hastened back to their farms and laid low. When Cornwallis finally arrived in Wilmington in May 1776, there were no Highlanders to greet him, only a chagrined Gov. Martin, whose foolproof plan to take back North Carolina had backfired. With no fighting Tories around to augment his own army, Cornwallis chose to sail for Charleston with the intent of attacking the Patriot stronghold of Fort Moultrie. With the Tories in disarray, armed resistance to the Patriots in North Carolina melted away. In short order, the Whigs cemented their hold on government by adopting a new constitution, electing Richard Caswell as governor of the new state, and levying property taxes.

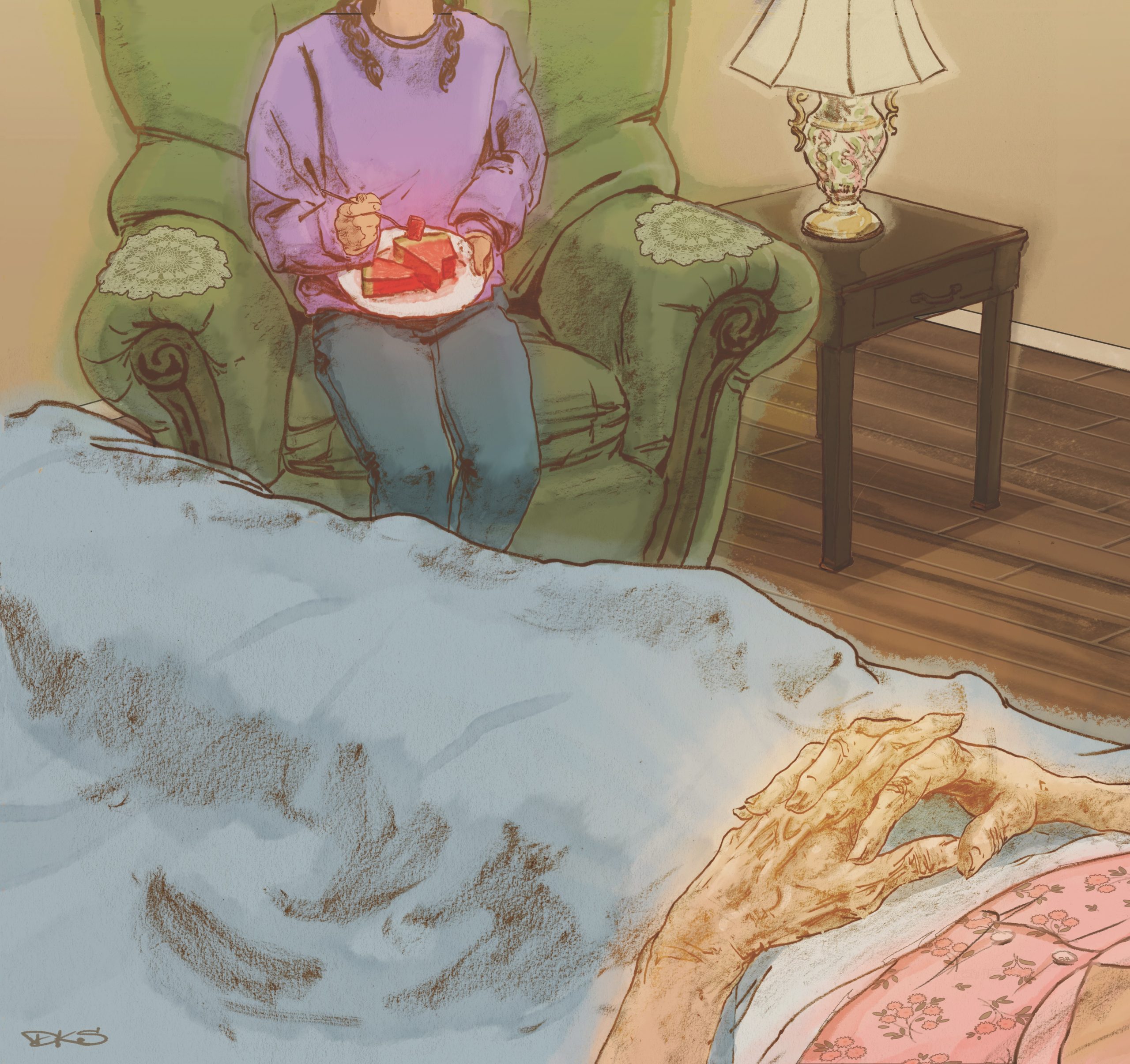

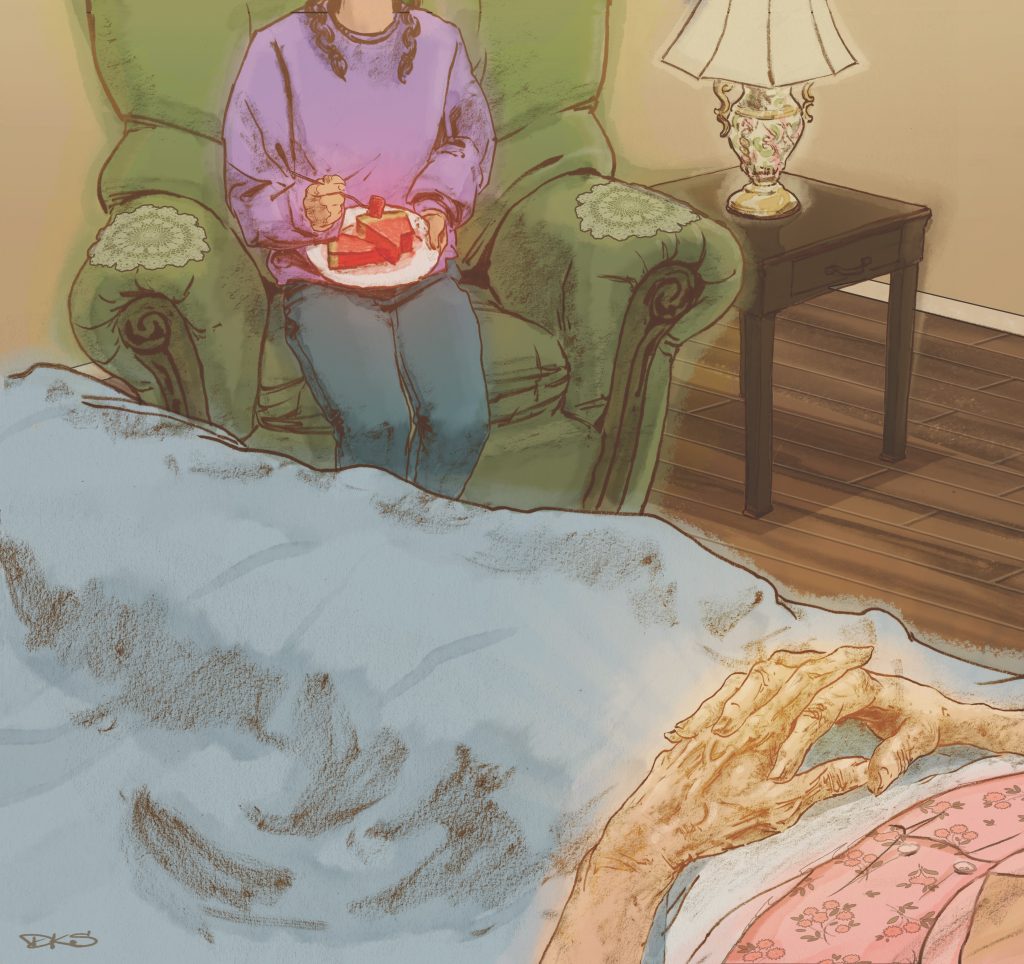

While there was a hiatus on military engagements in the state, the Highlanders’ troubles continued. Flora MacDonald’s home at Cheek’s Creek was ransacked and seized. Poor Flora! Once again, she had cast her lot with the losing side. Now age 54, homeless, separated from her husband, and a pariah, she appealed to Kenneth Black for help. He allowed Flora to hide at his Little River property, where she remained until reuniting with Allan after his release in a prisoner exchange. In 1779, the couple left America and returned to Skye.

Kenneth Black himself ran afoul of the four-fold tax that the authorities imposed on those who refused to take an oath to the new state. This led to an altercation reported by Caruthers in his treatise. In the fall of 1778, an unintimidated Black rebuffed the efforts of two tax collectors for the county who came to his home.

Subsequently the taxmen brought in reinforcements, who promptly seized “a negro man, a stud horse, and a good deal of other property, amounting in all to seven or eight hundred dollars.” Black offered no resistance. Caruthers offered the view that given the rough treatment afforded Black, “a man in good circumstances, and of much respectability in his neighborhood . . . we may suppose it was worse with men of less property and influence in the community. During this period the Scots complained bitterly of such military officers as [Philip] Alston [and others] . . . for carrying away their bacon, grain, and stock of every description, professedly for the American army, but without making compensation, or even giving a certificate, and thus leaving their families in a destitute and suffering condition.”

Labeled by local historian Rassie Wicker as a “swashbuckling, aristocratic rascal,” Philip Alston wore many hats during the Revolutionary years: tax assessor, justice of the peace, and member of the legislature. And he was certainly a man of means. His wife, Temperance Smith, came from a wealthy family. Alston’s land holdings — mostly in the Deep River area, and including the House in the Horseshoe, totaled nearly 7,000 acres, and he owned slaves. But Alston sensed that the best way to further his emerging political career would be to lead his men into battle. Eager to join the revolutionary fray, he sufficiently impressed his Patriot superiors to be named First Major of the Cumberland County Militia. But after heading south, his regiment was mauled in the Battle of Briar Creek, Georgia, a stinging defeat for the Patriots. Alston was taken prisoner, but later escaped. As he made his way back to North Carolina, Cornwallis’ army was finally gaining a solid foothold in the South, having overrun Savannah and Charleston by May 1780. Moreover, British Maj. James Craig successfully occupied Wilmington in January 1781, so Cornwallis now had available a North Carolina sea coast supply base and garrison.

With Patriot prospects in the South on the downslide, Gen. Horatio Gates, the victorious American leader at the Battle of Saratoga, was placed at the helm of the Patriots’ “Southern Department.” But Gates suffered a humiliating defeat after marching his troops, including 1,200 North Carolinians, into the jaws of a surprise attack by Cornwallis at Camden, South Carolina.

Gates’s failure at Camden caused George Washington to replace him with Gen. Nathaniel Greene. Intent on demolishing the new leader’s troops, Cornwallis re-entered North Carolina and pursued Greene northward through the Piedmont. In the process of fording a stream, Cornwallis’s troops discovered that Greene had dumped tar in the stream’s bed to hinder the British crossing — one of a couple derivatives for the nickname “the Tar Heel State.” The adversaries met in battle on March 15, 1781, at Guilford Court House near Greensboro. While the engagement was declared a British victory, it was a Pyrrhic one. The heavy casualties on both sides hurt Cornwallis far more than Greene. With his army depleted and running low on supplies, a frustrated Cornwallis abandoned his pursuit of Greene and marched to Wilmington for refitting. He then departed that city with his army for Virginia on April 25.

While Cornwallis’ forays into North Carolina failed to subdue the Patriots, his presence nonetheless reignited Tory resistance. Young David Fanning emerged as a resourceful and ferocious leader of guerrilla-fighting Tories who terrorized the countryside in 1781. Much had happened to Fanning in his 10 years since leaving home at age 16 to escape the cruel treatment he endured as a child. After a period of wandering, he was rescued in Orange County by the O’Deniell family. The O’Deniells restored Fanning to health and cured him of the “tetter worm” disease that had caused the loss of his hair. They taught him to read and write. At age 19, Fanning settled in South Carolina, and traded with the Catawba Indians. When the Revolution came, Fanning favored the Whigs’ cause. However, according to Caruthers, everything changed when, “. . . on his return from one of his trading expeditions, he was met by a little party of lawless fellows who declared themselves Whigs, and robbed him of everything he had . . . [H]e at once changed sides and in the impetuosity and violence of his temper swore vengeance on the whole of the Whig party.” He then joined a Tory group of militants in South Carolina, until returning to North Carolina in tandem with Cornwallis’s army in early 1781.

Though not receiving any formal command from the British, Fanning nonetheless became a feared foe of the Patriots. Caruthers reports, “He was often upon his enemies when they were least expecting it, and having accomplished his purpose of death or devastation, he was gone before their friends could rally. Often when supposed to be at a distance, the storm of his presence in a neighborhood was communicated by the smoke of burning houses, and by the cries of frightened and flying women and children.”