Our House, Our Town

Finding serendipity on Massachusetts Avenue

By Deborah Salomon

Photographs by John Gessner

When the Roaring ’20s crashed in 1929, so did construction of luxurious winter residences in Southern Pines. One exception was a Dutch Colonial- style home designed by Alfred Yeomans in 1930 on prime Massachusetts Avenue acreage. Yeomans, a landscape designer and James Boyd’s cousin, had built the Highland Inn a few blocks away with Aymar Embury II. The new home on Massachusetts was owned by two daughters of Julia Anna “Annie” DePeyster of Ridgefield, Connecticut — Estelle Hosmer and Mary Justine Martin.

The DePeysters, mother and daughters, were typical of urban high society flocking to Southern Pines and Pinehurst for the mild winters. The family tree included two Colonial mayors of New York City. Another descendant, Frederick DePeyster, was a loyalist who fought on the side of the British in the Revolutionary War, was exiled to Canada, returned as a wealthy merchant, and rejoined New York’s social and economic elite. Annie DePeyster’s husband, Johnston Livingston de Peyster (a variant of DePeyster) enlisted in the Union Army at 18 and was credited with raising the first Union flag over the Capitol Building in Richmond, Virginia, after the city fell in 1865. He passed away in 1903. Why the sisters sold the fully furnished house in 1936 to the Catholic Diocese of Raleigh for half price remains a mystery, though Annie passed away a year later at the age of 90. William Hafey, the first Catholic bishop of Raleigh, kept his elderly father there; and Elizabeth Sutherland, a founding member of the Southern Pines Garden Club was a subsequent owner.

How very proud Yeomans, Embury (who built himself a cottage nearby) and the DePeysters would be of their accomplishment, now curated by Mary and Mike Saulnier. The flower, vegetable and herb gardens flourish, laid out and tended by novices who learned as they dug, moving and preserving decades-old plants. The house itself gains personality from irregularities and novelties — off-center dormer placement, angled walls, an exposed brick chimney rising two stories, a back stairway leading to the maid’s room (now a guest suite), a pair of interior windows, massive original bathroom fixtures and black-and-white tiled floors, a call bell system for the servants, and an under-the-stairway closet where hangs a clever fire extinguisher. Iron radiators, some covered with perforated screens, have been left in place as icons of the pre-forced air heating/AC era.

By way of introduction, in the foyer hang Yeomans’ architectural drawings, an homage to history beautifully framed by the Saulniers.

“I found them in the basement,” Mary says. That find inspired her to compile a scrapbook containing newspaper clippings about the house and its wealthy occupants, as well as other schematics. Because for Mary and retired Army Col. Mike Saulnier, this home represents another type of find.

“We were looking for a hometown,” Mike says.

Mary spent part of her childhood in Alaskan whaling villages, where her father taught in a one-room schoolhouse, later relocating his wife and eight children to Pennsylvania. Mike, from a military family, moved around. They met at Shippensburg University. Beginning in 1999, the military and NATO posted Mike, Mary and their children to The Netherlands, Belgium and Korea, sometimes for several years, with plenty of time to absorb the culture and acquire household goods.

The homesteading desire appeared in 2009, when they were stationed at Fort Bragg.

“We were sitting at the beach, trying to figure out where to live, since we didn’t have any connections,” Mary recalls. While browsing online she found a Weymouth listing that sounded attractive. They drove over and instantly fell in love with the area and, subsequently, the Dutch Colonial, which had been renovated and needed only painting (Mary and Mike did the interior themselves), window treatments, landscaping and minor adjustments.

“It felt right. We never looked anywhere else,” Mary says. Neither golf nor horses influenced their decision.

They moved in 2011 and began making the house their own. An unusual rectangular pool, for example. This came about when Mike discovered nothing would grow on that patch, also that a pool would cost less than a flagstone terrace. But nothing motel-style. He laid out the shape with ropes and hoses. “We wanted it to look like a water feature that had always been here.” The result, a safe 5-foot depth with a grayish pebble lining that makes the pool fade into the surroundings. An ozone purification system replaces chlorine. Add a few lilies and he’d have a pond.

Crumbling bricks on garden walls were made on premises by Yeomans, and a Dutch wooden gate replicates the one hung by the architect.

The main floor has a circular plan; turn right inside the front door, go through the dining room, kitchen and family room, windowless office and into the living room, which opens onto a screened porch. The only addition, by a previous owner, was the family room, which begs the question: Why are the walls angled in several directions?

Mary explains that the room was built not to disturb an ancient tree, perhaps a sugar maple like the huge one with dense canopy that shades and cools a portion of the yard.

That tree, a grassy lawn and boxwoods bring New England to the piney Sandhills.

If only nations could live as harmoniously as the furnishings the Saulniers collected in Europe and Korea. An Asian aura prevails, serenely, without resorting to red lacquer. A set of calligraphy brushes on a runner printed with the Korean alphabet adorn the foyer table, hinting at what lies within. Folding screens serve as headboards. Bells line shelves. A step-down bedroom chest, Mary explains, is finished and operational on both sides making it suitable as a room divider. But for every Korean artifact there is a table, a dresser, a desk or bookshelf — some carved antiques, others plain and functional — acquired at auctions in Belgium and Holland.

“I am naturally attracted to rustic and classic in muted tones,” Mary says. Her palette flows from moss greens and woodsy browns to oatmeal, linen beige, deep maroon and putty. Dusty turquoise appears briefly in the living room alongside an 18th century Flemish tapestry, with a few brightly colored Vietnamese bed coverings upstairs. Mary chose other fabrics with contemporary motifs. She and Mike upholstered bedroom headboards themselves using only plywood, padding, damask and a staple gun. In fact, “Everything we did is the first time we did it,” Mary says. Original oak and pine floorboards host carpets Mike brought back from Afghanistan. Beams cross the living room ceiling but this is not a house weighed down with crown moldings. Instead, objects like a colorful child’s kimono hung from a curtain rod practically jump off the slightly textured plastered walls.

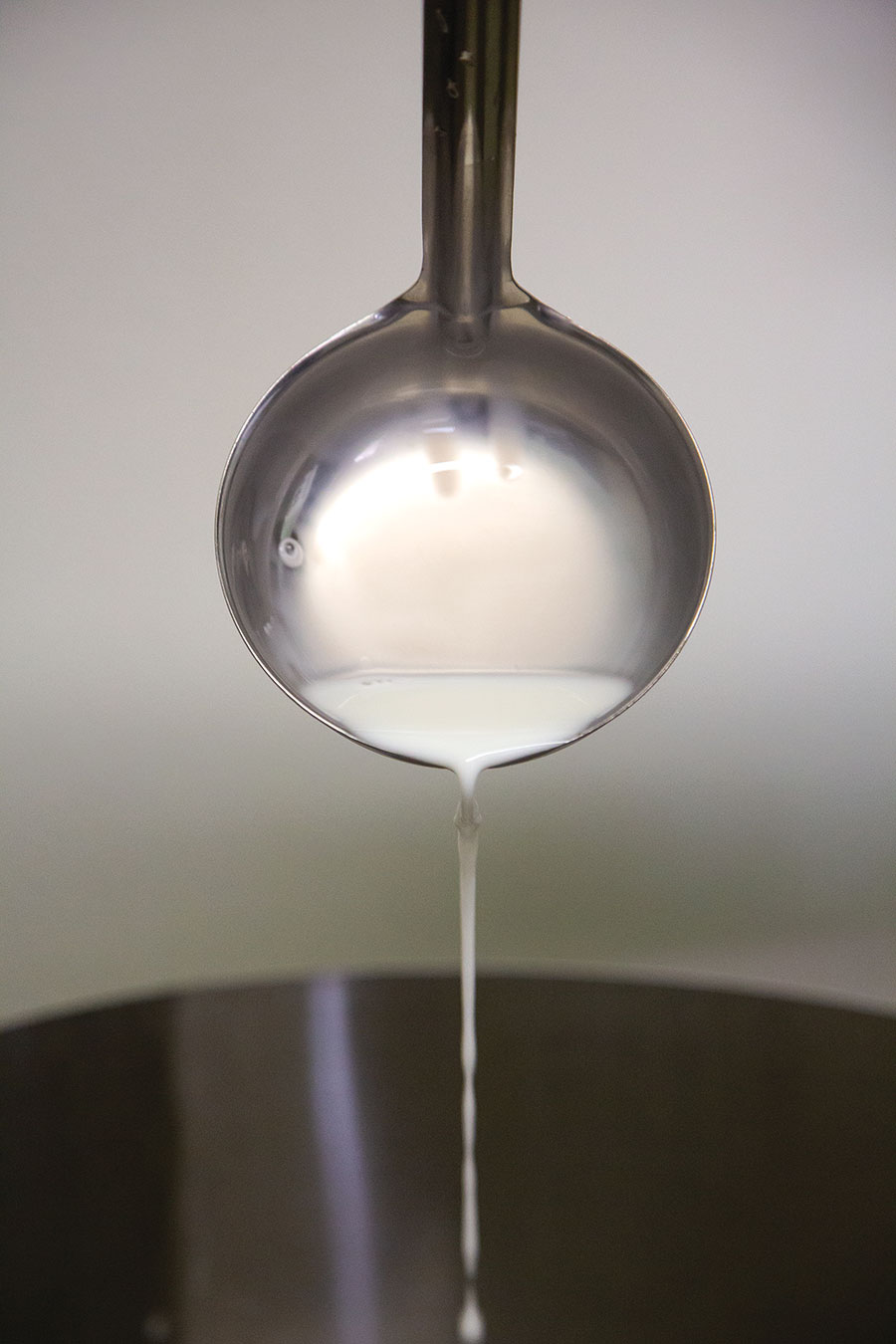

In the DePeyster’s era a small galley kitchen was sufficient for the hired cook. Now, when houses sink or swim in the kitchen, the Saulniers’ bypasses glitz and gadgets for warmth and European country charm while providing every amenity. An L-shaped layout, beadboard cabinetry (except for a few original carpenter-mades), thick natural wood and Provençal blue ceramic countertops, a French Quimper tile backsplash, a small vegetable sink in addition to the oversize farmer model, make it a comfortable and convenient place to prepare meals. In a corner stands an antique baker’s rack holding Mary’s pride: a collection of polished copper pots and skillets without which a French chef wouldn’t attempt even a scrambled egg.

More than 3,000 square feet on 1 1/2 acres seems generous for two people and a cat. Yet no room (except for the family room adjoining the kitchen) is oversize. Mary thought ahead. “The kids are gone but we want them and the grandchildren (two, already) to come home and stay in the house for holidays and make noise.” Besides, she continues, the way the house is configured, when one area gets noisy other spaces, indoors and out, offer alternatives for quiet conversation.

Back to finding a hometown. As with the house, Mary and Mike Saulnier lucked out. “This area has a real blend of cultures and people and viewpoints,” Mary says. “You go to an art exhibit and every person you meet is from somewhere else — but it’s still a small town.” A small town graced with historic homes, preserved and furnished with fascinating memorabilia of lives well-lived, including theirs. PS

By 2011, Paradox Farm was a licensed creamery. “Since then we’ve been growing the herd, making and selling cheese, and expanding our markets,” says Stovall. She hasn’t done it alone, but she has done much of it without Hunter. Sue grew up in Plainview, New York, in roughly the geographical middle of Long Island, near Bethpage State Park. She has three degrees in physical therapy, including a Ph.D. from Boston University. Hunter grew up in Virginia, went to the University of Virginia and Campbell University School of Law. Hence the “pair of docs.”

By 2011, Paradox Farm was a licensed creamery. “Since then we’ve been growing the herd, making and selling cheese, and expanding our markets,” says Stovall. She hasn’t done it alone, but she has done much of it without Hunter. Sue grew up in Plainview, New York, in roughly the geographical middle of Long Island, near Bethpage State Park. She has three degrees in physical therapy, including a Ph.D. from Boston University. Hunter grew up in Virginia, went to the University of Virginia and Campbell University School of Law. Hence the “pair of docs.”