“Little old bookbinder” Don Etherington held — and preserved — history with his hands

By Jim Moriarty

Photographs by John Gessner

Surrounded by thickheaded hammers, scalpels that look like they’ve escaped from an operating theater and a cast iron vice, Don Etherington sits on a stool in his bookbinding workshop and talks about the heart attack that led to his quadruple bypass surgery as if it was a trip to the Circle K. It was a delightful, warm November day a little over a year ago. He had turned 80 a few months before. He felt a sharp pain in his chest, took a nitroglycerin pill, waited five minutes and took another. The pain didn’t go away so he called 911. His house is four from the corner. By the time the paramedics got him to the end of the road, he was gone.

From the other side of the studio, his wife, Monique Lallier, a designer of artistic book covers as highly prized as Etherington’s own, picks up the narrative. “He said, ‘You know this nurse in the ambulance, she was sooo nice,’” she says, her French-Canadian accent making the encounter in the rear of a rescue vehicle sound just slightly naughty. “I said, ‘Of course she was nice, she was happy to see that you came back.’”

Etherington laughs. “So,” he says, “this is my second time around, actually.”

The first one wasn’t half bad.

“I’m just a little old bookbinder,” Etherington says. Indeed, he is. One who has laid his hands on the 1297 Magna Carta and the Declaration of Independence, to name just two. And it all started with a pair of dancing shoes.

Born in 1935, living in a Lewis Trust building — flats for the poor — in central London, Etherington was a child of the Blitz. His mother, Lillian, cleaned houses. His father, George, was a painter by trade who’d been a prisoner of war for four years during the War to End All Wars and came home a changed man. “He was a hard guy,” Etherington says.

With the exception of roughly half a year when Etherington was evacuated to a house in Leeds that lacked indoor plumbing, buzz bombs and shelters were what passed for a routine childhood. “I used to roam the streets with a bunch of guys,” he says. “I’d go around at night — I can’t believe this myself — with a shopping bag and pick up all the pieces of German shrapnel. I’m, what, 5? It’s beyond imagination. The Blitz, the only time it really affected me, was when the flats got bombed. That night 73 of my school chums got killed in that one air raid. I think it was a doodlebug (a V-1 bomb). It hit the corner of our apartment block, skidded into the shelters, where a lot of people got killed, and it bounced off there into the school.

“It was like part of life. You’d hear the drone coming over and then all of a sudden, it would stop. We could tell where it was going to hit. We’d say, ‘Oh, that’s going to hit Hammersmith or that’s going to hit Kensington.’ We didn’t have that feeling that it was awful and depressing. It was our life. When you go through that, certain things don’t affect you as much. Basically, what I’m trying to say is that we were very resilient and resourceful.”

After the war, barely into his teens, Etherington did two things that would change the trajectory of his life, and he doesn’t know why he did either one. First, at 13, given a list of potential fields of study at the Central School, he ticked off bookbinding, jewelry making and engraving. He was chosen for bookbinding and off he went, still in short trousers. “I came away that first day knowing I loved it,” he says. “From that day on, nearly 70 years, I’ve been happy doing what I’ve been doing, which is very special.”

The second was those shoes.

“I took myself off the streets,” he says. At 14, he bought a pair of dancing shoes, marched into a studio in what was, to him, the fancy Knightsbridge section of London, and took up ballroom dancing. Medals and jobs came his way. He met his first wife, Daisy, when he helped open a dance studio in Wimbledon. “To this day, I don’t know how I went from strolling the streets, getting into all sorts of stuff, from that to doing dancing. The only thing I could say is when I went to Saturday cinema, I loved watching Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. I got enamored and thought, boy, I’d love to go to America.” Etherington danced his way into his 80s, including at Green’s Supper Club in Greensboro.

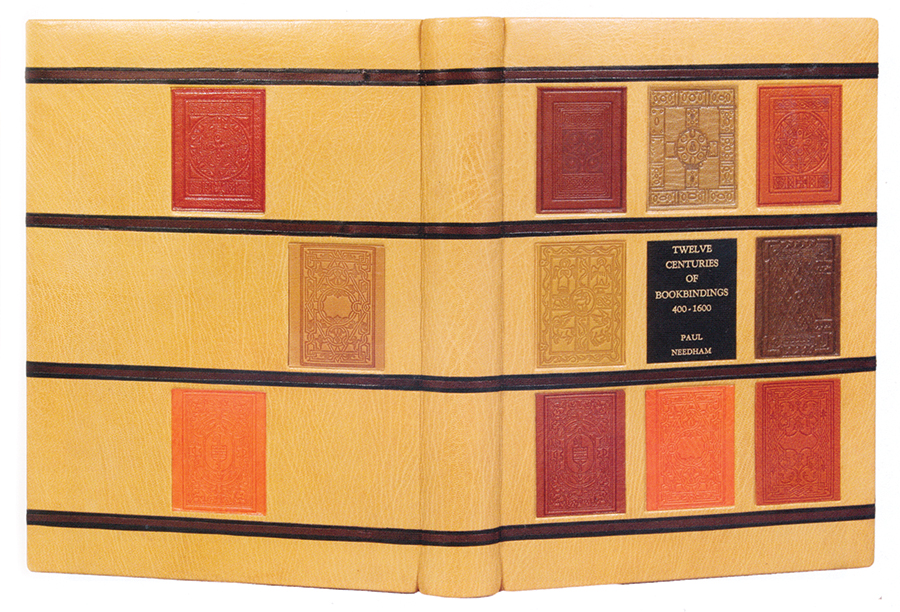

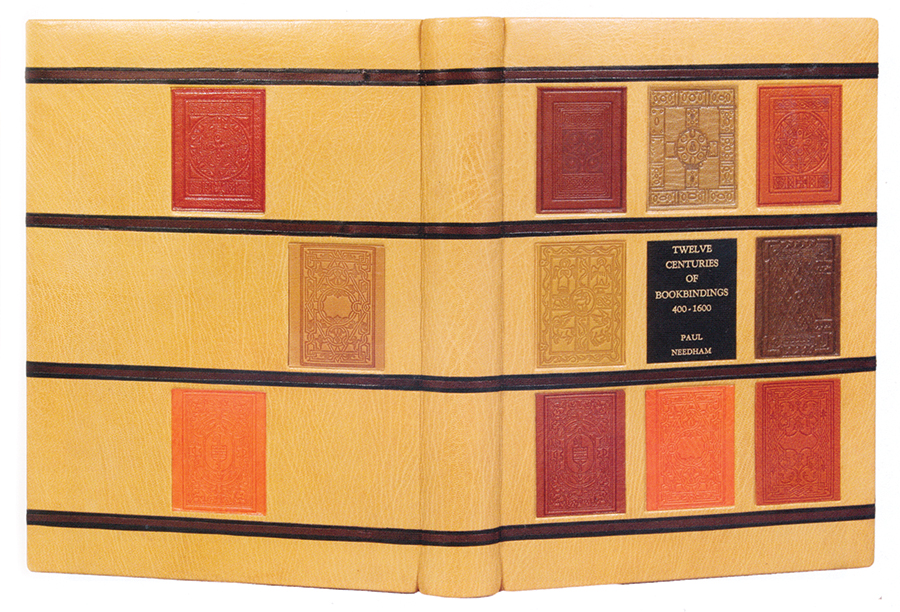

After a seven-year apprenticeship in binding at Harrison and Sons in London, followed by a brief stint restoring musical scores at the BBC, Etherington took a position as an assistant to Roger Powell, the man who bound the illuminated manuscript The Book of Kells into four volumes in 1953. “I went to Roger. He said, ‘What do you know about bookbinding?’ And I said, ‘Absolutely everything.’ For the next few years he showed I didn’t know a damn thing,” says Etherington. His work with Powell and his partner, Peter Waters, was followed by a position at Southampton College of Art, where Etherington developed a bookbinding and design program in addition to producing his own designs, the artistic covers he’s created throughout his life.

In the first week of November 1966, after a period of prolonged rain and threat of the collapse of several dams on the Arno River, a release of floodwater hit Florence, Italy, traveling nearly 40 miles an hour. The Biblioteca Nazional Centrale, virtually under water, was cut off from the rest of the city. The damage was incalculable. Powell and Wright asked Etherington to join the British team being dispatched to Italy to help. “They had 300,000 books floating in the water. Before we got there these student volunteers got them out of the water, out of the mud, out of the oil and put them on a truck to be dried in tobacco kilns up in the mountains. Not to blame them because nobody knew, but it was the wrong technique. Here you’ve got covers floating all around and you’ve got books floating all around. In those days, they weren’t titled. All these scholars were having to try to match up that cover with that book with no indication other than size.”

Out of this disaster, the field of book conservation was born. “We started to talk to German, Danish, Dutch bookbinders and restorers for the first time. We started talking about different techniques. Never would anybody share secrets — including England. All of a sudden, we’re talking together around coffee or whatever. It was just a whole different mindset,” says Etherington.

For two years, he spent between six and eight weeks in Florence teaching conservation techniques to the Italians. His first trip to Italy, at the age of 31, was the first time he’d ever been on an airplane. Etherington stayed in a pensione on the Arno River whose owner looked like Peter Sellers, and his fellow lodgers included two bankers from Milan, a prostitute who didn’t talk much, and a countess who had been married to a high ranking German general in the Weimar Republic who delighted in regaling her dinner companions with personal recollections of the Aga Khan.

Etherington would, himself, hit on a previously untried technique, using dyed Japanese rice paper in mending leather bookbinding to add strength unachievable with the leather alone, an approach that’s still used. “People give him a lot of respect for being one of the early conservators,” says Linda Parsons, who joined Etherington at the founding of what would become known as the Etherington Conservation Center (now the HF Group) in Browns Summit.

Four years after the Florence flood, Etherington was asked by Wright to join him at the U.S. Library of Congress as a training officer. He spent a decade in D.C. in various capacities. Among the projects he consulted on were teaching FBI agents about printing techniques, typefaces and paper characteristics to help them reassemble shredded documents found behind the Democratic party offices at the Watergate Hotel — some of which related to the scandal itself — and preparing Lincoln’s manuscript of the Gettysburg Address for display at the Gettysburg National Military Park. As if he had nothing else to do, Etherington penned a full-blown dictionary, Bookbinding and the Conservation of Books, listing every tool, material and technique related to the field he’d help create.

From the Library of Congress, Etherington was hired to launch a conservation program at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center at the University of Texas in Austin. There he was asked by Ross Perot to supervise the care and transportation of the 1297 version of the Magna Carta.

“There’s about 17 versions in existence. The 1297 one was the version the Founding Fathers used to write the Constitution of the United States. Ross is a big collector of Americana. He bought it for $1.5 million, which was pretty cheap at the time. It was found in the archives of a family in England. I was very surprised that England allowed it out. When I saw it, it was in really, really good shape. The ink was very black. There was question whether it was legitimate. Many scholars looked at it and authenticated it but, boy, it was questionable at the time.

“When you have an early document, you have a seal — I think it’s Edward I — and a silk strap. Because of maybe packing it or making sure it didn’t hang loose, someone turned the tie and put it on the back and stuck Scotch tape on it. I know it sounds stupid but it was that way. At some point, it went up for sale. This guy bought it for $22 million so Ross didn’t do too bad.”

By 1987, Etherington had fallen in love with Monique on a trip to Finland. His sons, Gary and Mark, were grown, and he decided to rearrange his life and leave Austin. He and Monique moved to Greensboro to begin a for-profit conservation company in association with Information Conservation, Inc. It would morph into the Etherington Conservation Center. The company performed the conservation and display preparation for the Constitution of Puerto Rico. They prepared and conserved the Virginia Bill of Rights. And Etherington was asked to work on the Charters of Freedom exhibit — the Declaration of Independence, the Constitution and the Bill of Rights — for the National Archives as the parchment consultant on the Declaration of Independence, helping to design how the badly faded document was to be displayed. Like a sure-handed heart surgeon, one concentrates on the process, not the patient.

“A lot of people who are not in this business, they think it’s a little bit scary,” he says. “I try not to think too much about the importance of it to history or to our country or whatever, because once you start doing that, instead of treating it with surety, you’re treating it with tentative hands, and that’s the worst thing that could ever happen to you.”

Etherington’s archive resides at the Walter Clinton Jackson Library at UNCG. “He’s internationally known,” says Jennifer Motszko, the library’s manuscript archivist. “He basically was there at the founding of his field where they started to come up with systemizing ways to preserve and conserve materials. But then he’s become a well-known entity in fine arts binding. You mention him in that circle, he and Monique define that area.”

In celebration of artists and their craft, the UNC Wilmington Museum of World Cultures has designated Etherington and Lallier North Carolina Living Treasures. Etherington has worked on everything from family Bibles to a 14th century Haggadah, from first century Chinese papyrus rolls to a rare copy of James Joyce’s Ulysses, from personal treasures to national ones. Still, every day at 5 p.m., studio work ceases. It’s time for the Etherington Cocktail. One part gin. Two jiggers of sweet Vermouth and a splash of tonic water.

“I’ve been very lucky doing things,” says Etherington.

Now he gets to toast a second go-round. PS

Positive Outlook

Preston McNeil met Don Etherington when the family’s Chi-Poo, Mali, a Chihuahua/poodle mix, gnawed the edges of the study Bible belonging to his wife, Brenda. McNeil, who moved to North Carolina from New Jersey in 1988, has owned businesses ranging from carpet cleaning to cookie stores, and dabbled in jewelry design. He decided he could add bookbinder to the list by taking the chomped-on Bible apart and putting it back together again.

“So, I did,” he says. “It was a book that worked.” All the new binding lacked was lettering. McNeil found a place where he could have it imprinted. When the man behind the counter made out the invoice he noticed McNeil’s address. It was the same street Etherington lived on. “He said, ‘Take this book and show Don what you’ve done,’” says McNeil. “So, I took it to Don and he goes, ‘Uh, I see some mistakes but you did pretty good.’ He invited me in. And I’ve been going to him from that point on.”

After a couple of years studying with Etherington, McNeil felt confident enough to redo a friend’s Bible. “Then I began to buy my own equipment. Now, I have a full studio downstairs,” he says. And another business, Gate City Binding. “I wish I had learned to do this when I was 36,” says McNeil, who’s actually three decades older than that. “I love it so much.”

His seven-year apprenticeship with Etherington and his new skill set led to a delicate and difficult commission, rebinding the volumes of the Pinehurst Outlook, the newspaper that published continuously from 1897 to 1961, that reside in the Tufts Archives at the Given Memorial Library. The project is being paid for entirely with donations designated for that purpose.

“The majority of the Outlooks I’ve worked with are fully separating from the original binding,” he says. “The spine is deteriorating. Everything is dry-rotting on the interior. The books are all newspapers. If they need to be restitched, they’ll be restitched. If they need to be reglued, I reglue them. Then rebuild the whole spine. It goes from individual papers to a book again. It’s building a book from scratch, essentially.”

Just like his new career is built from scratch. “I take from his mind, put it into my mind,” says McNeil of his mentor, Etherington. “I take from his hands, and I hope it’s coming out of my hands.”