BIRDWATCH

Swamp Song

A liquid stream of notes

By Susan Campbell

To most folks, especially non-birders, a sparrow is just a sparrow — a small brown bird with varying amounts of streaking and a stubby little bill. Not very impressive. However, in Central and Eastern North Carolina, and especially in winter, nothing could be further from the truth.

Although few sparrow species can readily be found during the breeding season in our area, we have 10 different kinds that regularly spend the cooler months here. These range in size from the husky fox sparrow down to the diminutive chipping sparrow. Without a doubt, my favorite in this group is the swamp sparrow, whose handsome appearance and unique adaptations make it a definite standout.

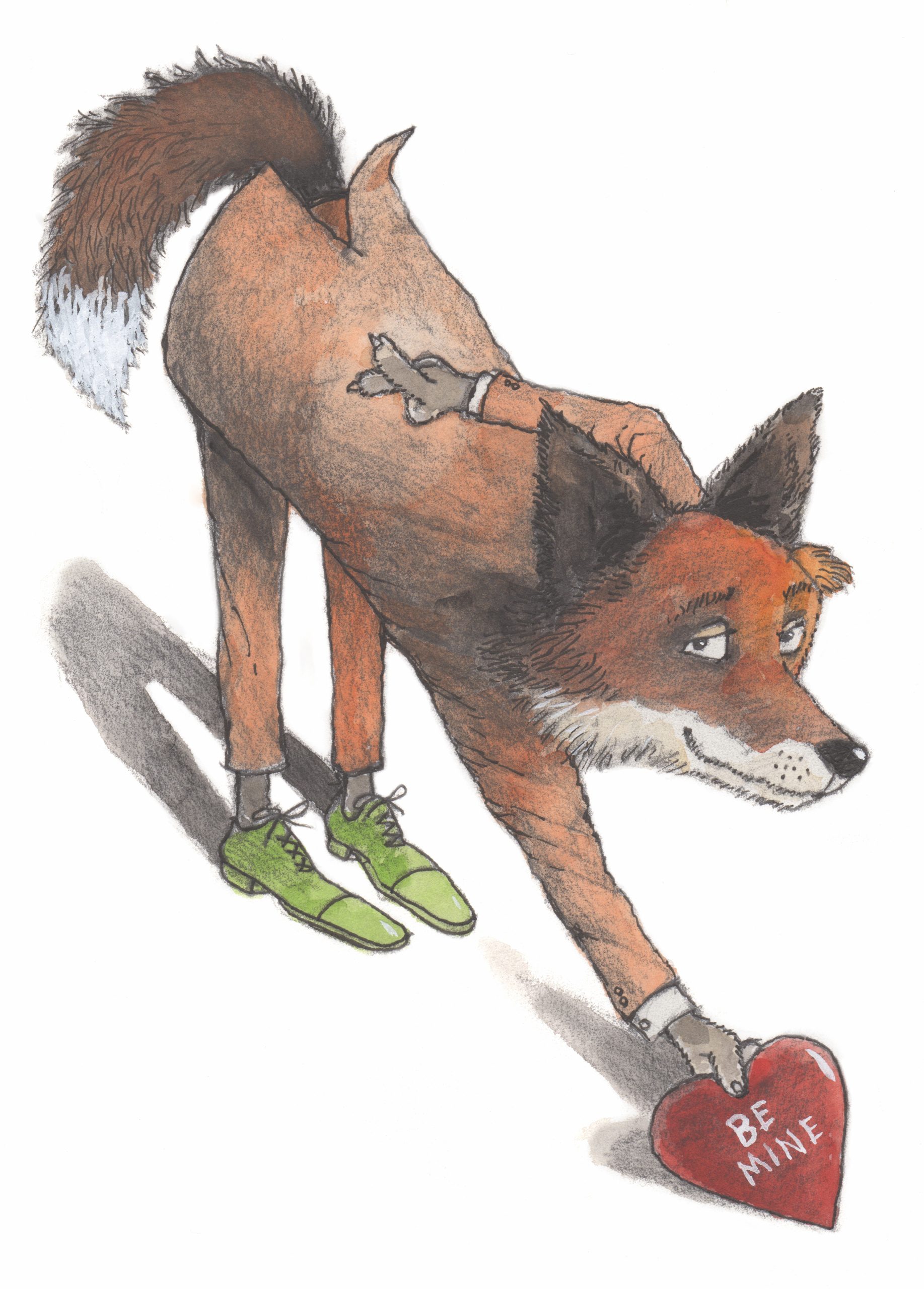

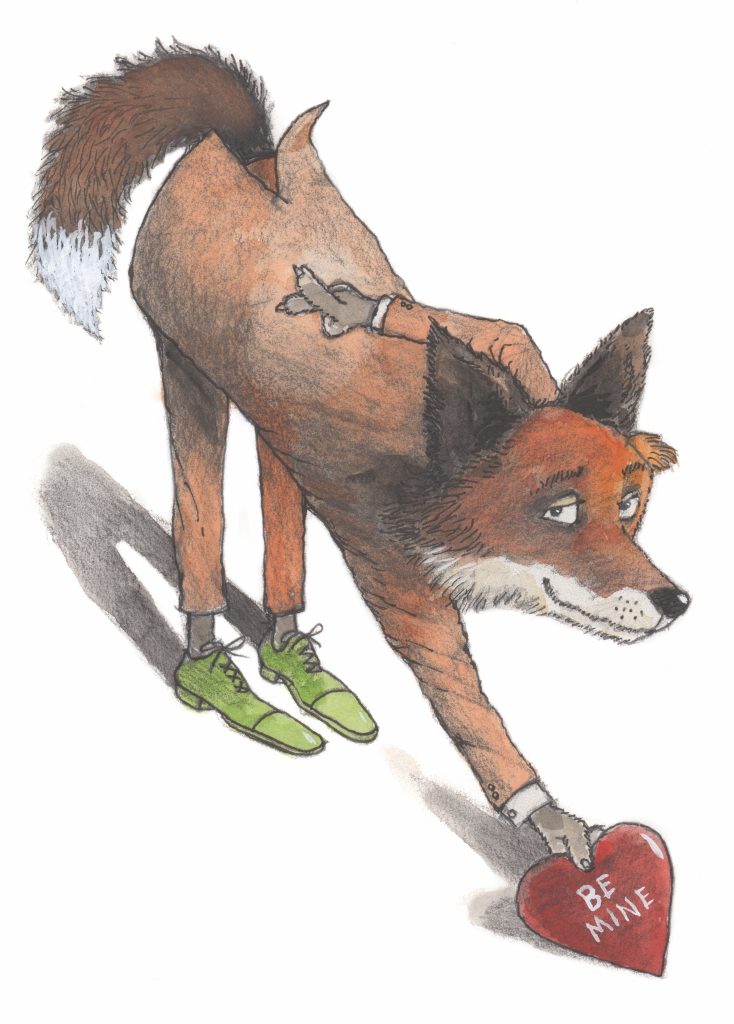

At this time of the year, these medium-sized sparrows are a warm brown above with black streaking — like so many others — but swamps have a significant amount of chestnut apparent in the wings. The gray face, dark eye line and crown streak contrast sharply with the white throat and breast. The tail is relatively long and rounded, a very good rudder for moving around in the tight quarters where these birds live.

As the bird’s name implies, it is usually found in wetter habitat year-round. With longer legs than their conspecifics, swamp sparrows readily forage in the shallows, searching not only for fallen seeds and berries, but also for aquatic invertebrates. Individuals are even known to flip submerged vegetation with their bills in search of a meal.

The song is a liquid stream of notes that we rarely hear during the cooler months. The call note, however, is very loud and distinctive and uttered frequently. I hear far more of these birds calling from thick, wet habitat than I see along our coast. Swamps give themselves away with a metallic “chink.” If they are disturbed, they are hesitant to fly — probably due to their excellent camouflage. Instead, these birds usually choose to run from potential danger. They can maneuver deftly through sticks, stems and branches when pursued.

If a swamp sparrow does fly, it will not be over a great distance. A leery individual will sail to the nearest perch and survey the source of the disturbance, and then it will quickly vanish into thick vegetation.

Birds of wet areas such as these can be attracted to your yard even if you do not live in a coastal or riparian area. They may show up during the spring or fall migration if you can create cover for them. Adding low, thick shrubs such as blueberries or gallberry will help. A simple brush pile adjacent to your feeding station may be enough to get their attention, but in order to really up the odds of attracting a few swamp sparrows, consider creating a small wetland garden. A small depression will attract more than just this species: It will provide for a multitude of native critters and can be used to naturally treat (i.e., filter) household wastewater. Water features of all sizes have become a very popular way to increase wildlife, even on small properties.

Swamp sparrows have been studied for almost a century. It was one of the first species to be banded by ornithologists using modern methodology in the early 1900s. In fact, a banded bird from Massachusetts in October 1937 was relocated in central Florida in January of 1938 having covered a whopping 1,125 miles. This information was some of the earliest data produced on the migration of songbirds in the United States.

The next time you are out walking along the edge of a marshy area or paddling in the shallows, watch and listen for this neat little winter resident. One may pop into view and treat you with a short look.