SIDE BY SIDE

Story of a House

Side by Side

When home is next door, too

By Deborah Salomon

Photographs by John Gessner

A Pinehurst palace outfitted with the accoutrements of fine living was not what Cathy Vrdolyak and spouse Marilyn Barrett, both successful Chicago professionals, sought in 2013. They wanted a retreat, a vacation home, something as low-key as their three-level, 3500-square-foot loft in a historic Chicago industrial building was top-echelon.

Golf and climate factored in, given the Windy City’s often brutal winters. Barrett knew the area; her father, a lawyer and musician, had performed and later retired to the Sandhills. What they found — a neglected cottage bordering a public works facility, probably built to house a tradesman’s family — became the rock from which they chiseled a mini homestead, unique in having wooden pegs instead of closets and a few refrigerated drawers instead of a hulking Sub-Zero.

Really? No closets? Classic utensils but no refrigerator? Not necessary, they decided, for a cuisine based on farmers’ wares, homegrown produce and a simple but interesting menu. Once completed, Barrett said the interior was “like walking into a hug.”

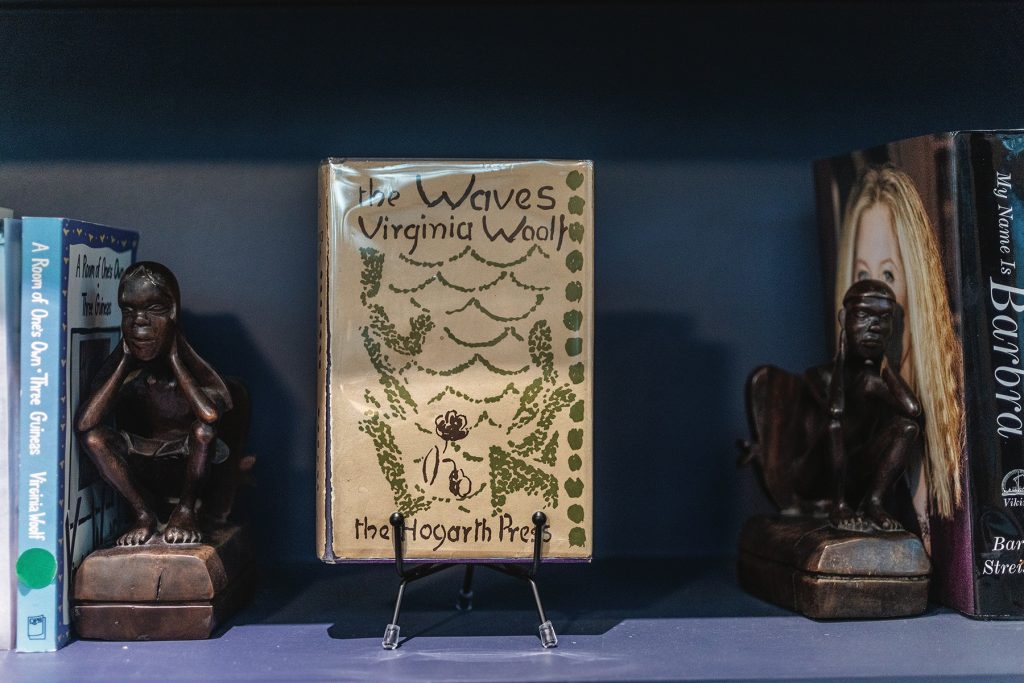

The women named their getaway, renovated by Pinehurst architect Christine Dandeneau, “Bloomsbury Cottage” after the literary coterie formed in the early 20th century that included British feminist author Virginia Woolf. The cottage layout and contents became the palette for the designer.

“She got it,” Barrett says of Dandeneau’s plans.

In addition to the cottage, Vrdolyak and Barrett have compact freestanding studios overlooking the gardens, lap pool, deck and a tall brick Croatian barbecue-oven.

Nearly a decade of weekends and vacations passed happily at Bloomsbury. Retirement loomed. The cottage has two tiny bedrooms and a loft accessed by a steep ladder, a tough ask for the nimblest houseguest. Besides, their elegant furnishings and collections from the Chicago loft needed a proper home.

As usual, the possibilities ran perpendicular to the norm. Maybe build a unit beside, but not connected to, the cottage, on the sliver of land tucked between Bloomsbury and the public works fence? Call it The Salon, in keeping with the European theme. Give it a 16-foot high wall of windows, a statuesque gas fireplace with exposed stovepipe and whitewashed wood floors laid in a chevron pattern. Opposite the window wall, construct shelves displaying dozens of cookbooks plus New York Times besties, writings of Virginia Woolf, crystal objets and, in the center, a bed that unfolds out, not down. Include a full bathroom, an ice machine, hot plate and, most importantly, a well-stocked wine refrigerator.

Here, detail-oriented CPA/attorney Vrdolyak calls attention to a barely discernable chevron pattern lining the sink and its handsome brass hardware that coordinates with the chevron floor. Their cottage may lack closets but The Salon, in addition to creativity and quality, offers ample storage.

The idea of a separate dwelling unit intrigued Dandeneau, who recognized it as part of a trend, limited in square footage but not in usage. “They are lovely clients who build with character,” Dandeneau says, “and they’re not afraid.” She was able to overcome a glitch locating the wall-hung fireplace but fulfilled her clients’ desire for a multi-purpose space suitable for social occasions as well as sipping mid-morning tea. The location screens The Salon from street view, not that there’s much traffic anyway.

Its predominant color is a dusty navy blue — drawn from the blue, crimson and yellow in the area rugs — that offers a striking background for oversized French wine posters, some liberated on their travels, and adored by Barrett.

“They were advertisements and I was in advertising,” she says. “So vibrant, they make me happy.” Two red velveteen, 1940s-ish easy chairs from Barretts’ parents’ home, further the retro mood. What better setting for a dinner party, game night, business meeting, or book club?

“It’s as though you’re going into a different era,” Vrdolyak says of The Salon décor. “Even the dogs come running, as though they’re going to another place.” Barrett, who practices yoga there, is still able to glance from her mat into the cottage through aligned windows. “It’s like getting a break from the everyday,” she says.

This side-by-side life “is definitely not for everybody,” says Barrett. But who cares? The concept, its execution and livability, is definitely for them.