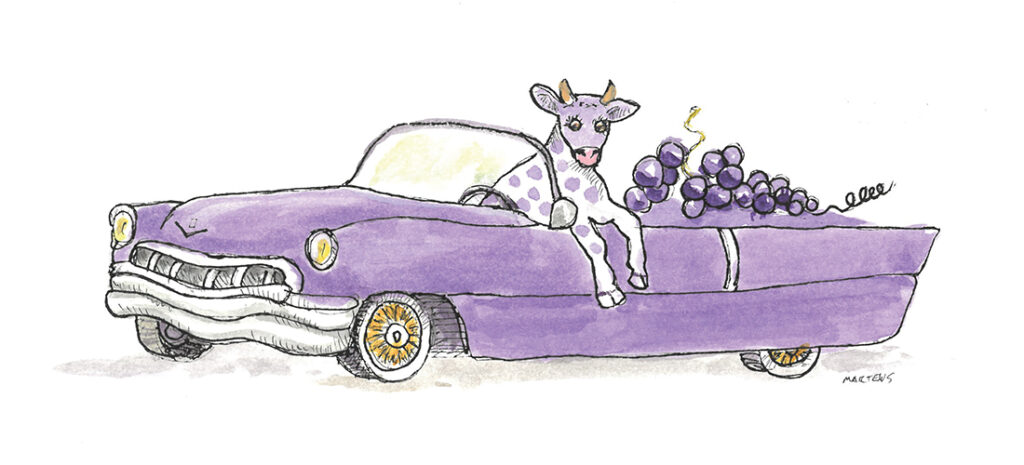

Focus on Food

Sláinte to Stew

The king of Irish cuisine

Story and Photograph by Rose Shewey

At the height of the Celtic Tiger, a time when Ireland’s economic growth was the envy of every Western nation, I was offered a job on the Emerald Isle. It was a no-brainer. I packed my bags, said my goodbyes and off I went to live and work in Ireland. To be more exact, I set up shop in picturesque Dún Laoghaire just south of Dublin, a town with a pretty port and a laid-back vibe and, as it turned out, right around the corner from Bono’s seaside residence — true story.

After my two-year stint there I can confidently share that a bunch of stereotypes floating about Ireland and the Irish have at least a couple of grains of truth to them. For one, Guinness does taste different on the island. Take this from a wine enthusiast. If I can tell the difference, you can, too. And, yes, drinking is a Celtic national sport. It is socially acceptable to drink at pretty much any point in time, with the exception of the time spent at your place of work — a minor constraint, but fear not, there is always lunch hour. So, that’s that.

More importantly — and this is a delicate one as far as stereotypes go — let’s talk about the legendary Irish cuisine. You’ve never heard of it? My point exactly. If the choices were soda bread and colcannon, I’d say Irish cooking was completely lost on me. But, fortunately, there is one dish the Irish know how to pull off. Their one saving grace — subjectively speaking, of course — is a hearty stew.

A purist at heart and always in search of the most authentic and original version of a dish, I made a couple of discoveries. To begin with, Ireland has as many “classic” and “traditional” Irish stew recipes as it has pubs. That’s a lot. Andrew Coleman, author of The Country Cooking of Ireland, probably nailed it with his attempt to capture the true nature of this recipe. His version simply calls for four ingredients: mutton, potatoes, parsley and onion. Irish stew, in days long gone, would have consisted of what people had on hand — mainly potatoes. If they were fortunate enough to have meat to add to the stew, they’d call it a feast.

That said, the most memorable Irish stew I have tasted was at the Guinness brewery in Dublin. A little bit richer and bolder than its rural counterparts, the Guinness beef stew may not be the most historically accurate rendition of this celebrated dish, but it is by far the most satisfying.

Irish Beef Stew with Guinness

(Adapted from The Official Guinness Cookbook, serves 4-6)

2 tablespoons olive oil

2 pounds chuck steak, cubed

2 onions, sliced

2 celery stalks, finely chopped

5 carrots, cut into large chunks

2 tablespoon all-purpose flour

1 bottle Guinness Draught Stout (440 milliliters)

1 cup beef stock

2 tablespoons apple jelly

2 tablespoons tomato paste

2 teaspoons prepared mustard

2 sprigs fresh thyme

2 bay leaves

8 ounces baby potatoes

Salt and pepper, to taste

In large skillet, heat oil and brown meat in batches, about 10 minutes per batch. Set meat aside, then add onion, celery and carrots to the skillet and cook until slightly softened, about 5 minutes. Sprinkle vegetables with flour, stir and cook for about 2 minutes, add Guinness and beef stock along with the remaining ingredients, except for the potatoes. Add meat back to the skillet, cover with a lid and simmer for 2 hours. Lastly, add potatoes and continue to simmer for an additional hour. Serve with chopped parsley and bread. PS

German native Rose Shewey is a food stylist and food photographer. To see more of her work visit her website, suessholz.com.

The concept

The concept