Harry Houdini, Thomas Jefferson, George Lucas and Ernest Hemingway collected books. Nicole Kidman collects coins. Demi Moore favors porcelain dolls. Tom Hanks loves old typewriters. Passion comes in all shapes and sizes. It’s not about stuff. It’s about the chase

By Will Harris

Photograph by Tim Sayer

Tony Rothwell

Tony Rothwell was 14 years old when he first encountered the work of British caricaturist James Gillray in the pages of a history textbook, and was captivated by the artistic talent and political depth of the work.

“I didn’t realize how interested I was in the graphic arts, but I thought this was so wonderfully graphic and so clever, I made my own copy of it,” Rothwell says.

The print Rothwell copied was Gillray’s “The Plumb-pudding in danger,” a caricature that still appears in history books. It’s an 1805 editorial cartoon of Napoleon Bonaparte and British Prime Minister William Pitt dividing a plumb-pudding globe into metaphorical spheres of influence — a comment on the world leaders’ appetite for dominance. “Fast forward and I’m now in London, 21 or 22 years old in my first job, and it was used as an advertisement for a show of Gillray prints,” Rothwell says. “I decided that I would turn London upside down and see how many would fall out, and they started falling. In those days, they weren’t that expensive. I was lucky I got in early before anybody was seriously collecting them.”

Gillray is credited with creating and popularizing the political cartoon as a genre, and the influence of his work was felt throughout Europe. He directed his sharp wit at both political parties (depending on who was commissioning him), but Napoleon, in particular, was a focus of his derision.

Rothwell has at least 150 Gillray prints and sketches. Although he has works by the caricaturist’s contemporaries as well, Rothwell is particularly impressed with Gillray’s political wit, breadth of knowledge and raw artistic talent.

“Gillray really was the first true political caricaturist. He invented it,” Rothwell says.

Gillray lived in a turbulent and exciting time, ripe for political discourse and caricature. Britain and France were competing for influence on the world stage. King George III and Napoleon Bonaparte lent themselves to the hyperbolized visual renderings that Gillray made so popular. It was also a time when the conventional methods of consuming news left something to be desired. Gillray saw an opportunity to put his artistic skills to commercial use, and opened a shop to sell his prints.

“Newspapers were all black and white and didn’t have any pictures at all, so this is how the wealthy could entertain themselves,” Rothwell says. “It was giving them news, and it was also giving them a laugh. At the same time, it was scaring pompous people, bringing them down a notch or two.”

Gillray’s influence extended to the upper reaches of the ruling political class. “He was being read by the House of Commons, by the royal family — people who had money and influence,” Rothwell says.

There’s no true modern equivalent to Gillray’s prints. They resemble today’s political cartoons but are packed with subtle cultural symbols, allusions to Greek and Roman mythology and detailed historical context. Because Gillray’s well-heeled audience was also well educated, he was able to elevate his imagery and symbolism.

“I’m in awe of the man really, still today. I think he’s incredible. He has set the table for so many caricaturists since,” says Rothwell. Expanding his collection has gotten easier with the advent of the internet. “In the early days it was all footwork but now, eBay walks a million miles for you every day. You make time for what you love”

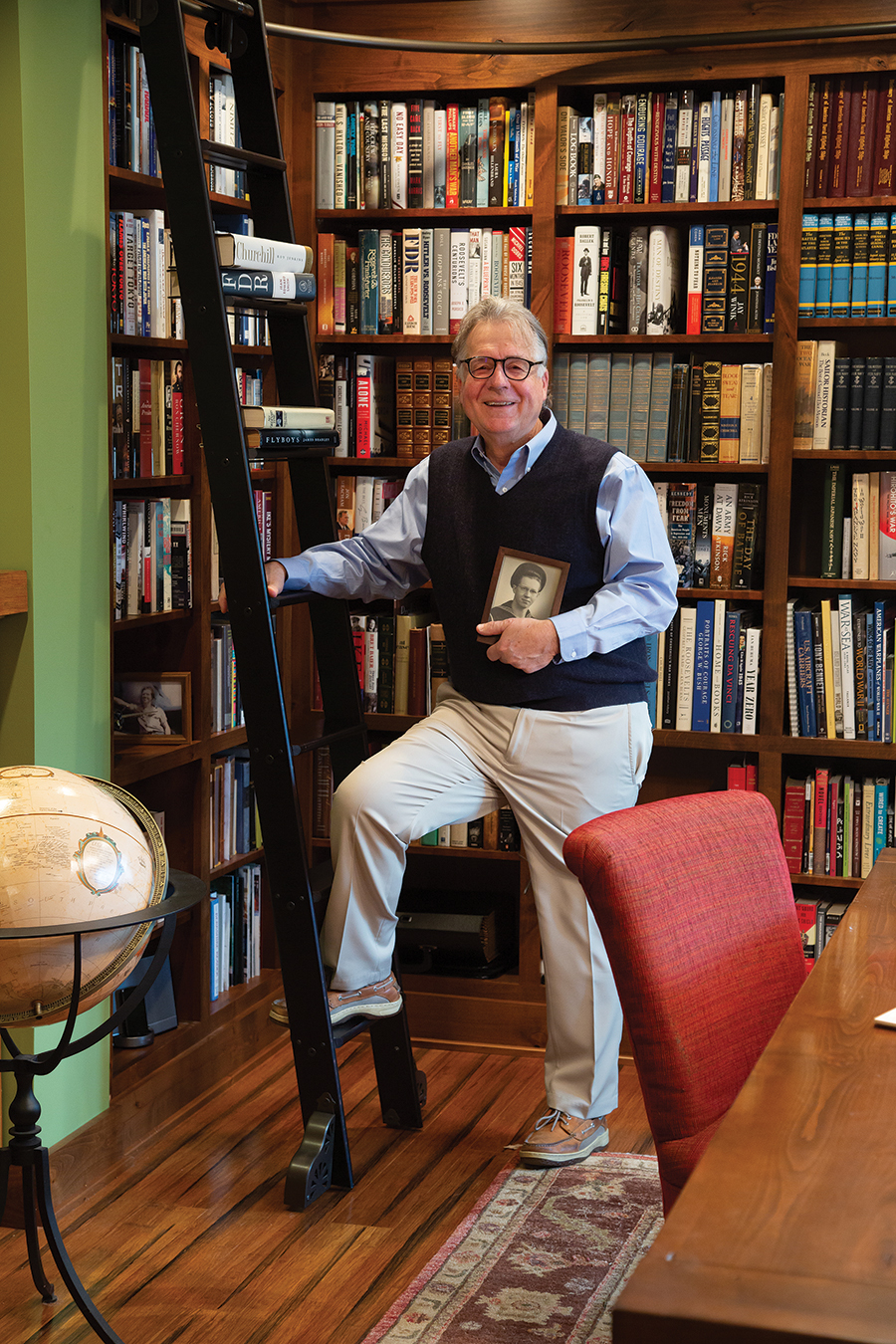

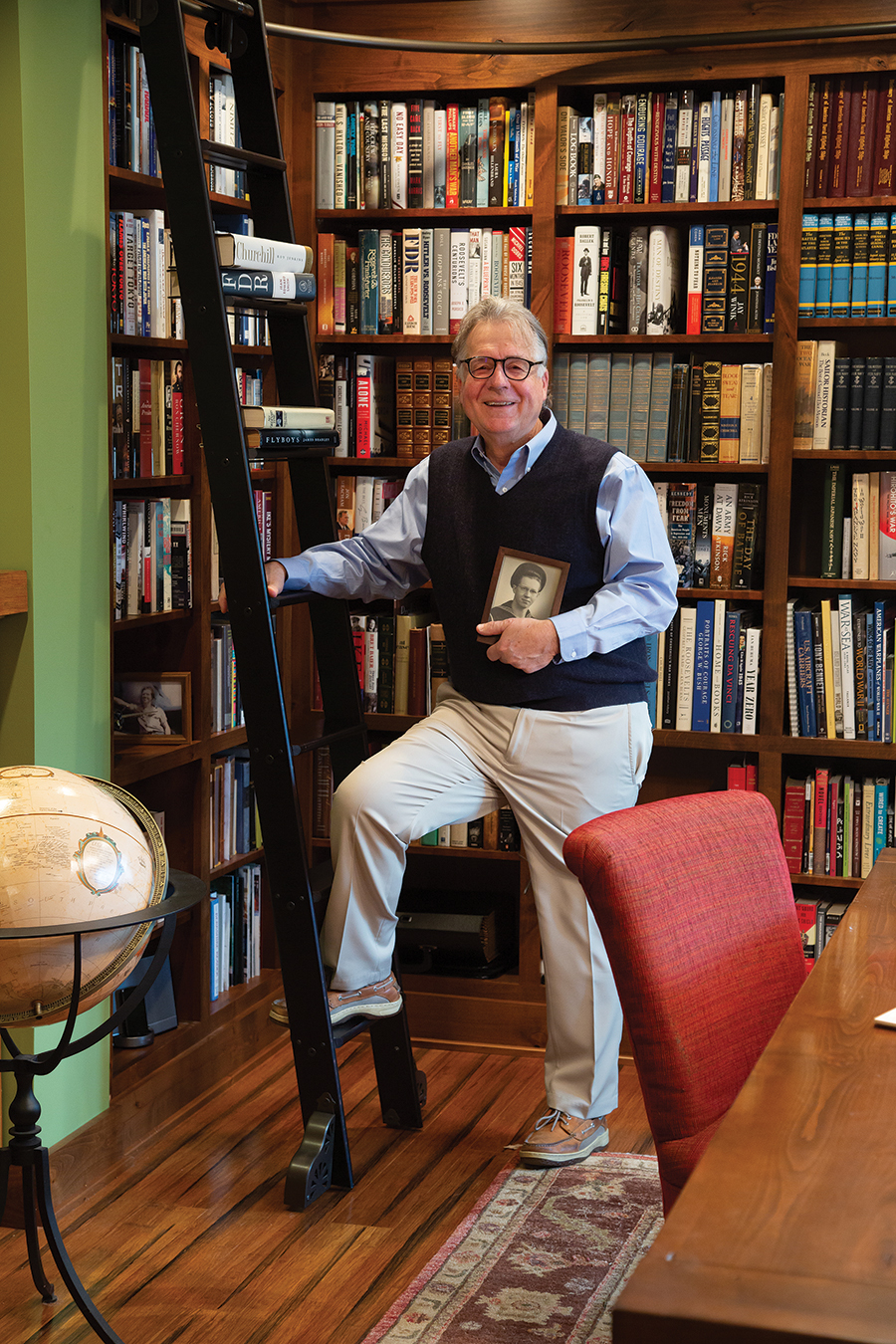

Photograph by Tim Sayer

Rick Smith

A self-described “pretty serious book collector,” Rick Smith has been afflicted with a passion for books since he was a child. “I fell in love with the tactile nature of books, how well they were bound and how colorful they were, the thickness and the weight,” Smith says.

This childhood curiosity gradually developed into a full-blown obsession. Today Smith’s library contains around 1,200 books with hundreds of signed copies. Three books in the collection are autographed by former U.S. presidents: George W. Bush, George H.W. Bush and Harry Truman.

Smith’s passion transformed his life in every respect, and his home is a testament to it. “My wife, Susie, said there’s room for two of us in this house but probably not for your books,’’ Smith says. He redesigned the garage of their lakeside cottage into a cozy personal library, complete with a rolling library ladder. A stained-glass lamp illuminates a massive worktable made from knotty alder wood.

Smith is particularly fond of his books related to his father’s (Richard H. Smith Sr.) service in the Navy during the Second World War. “One of the things I began to wonder about was how my father’s life was transformed by his, albeit brief, time in the service as a very young man,” Smith says. “I think he was inspired by that, and so I decided there are probably threads in this that need to come out.”

Smith’s father was a seaman first class on the aircraft carrier USS Bennington and the plane captain (crew chief) assigned to a one of the ship’s TBM Avengers — aircraft originally designed as torpedo bombers. His job was to ensure the bomber under his purview was combat ready.

In 2003 James Bradley published his best-seller Flyboys. It details the harrowing 1942 air raid of Chichi Jima by TBM Avengers. Among the pilots was 19-year-old George H.W. Bush.

Smith’s father felt a special connection to the former president through their shared experience with the TBM Avengers, so Smith bought a signed copy of Flyboys as a gift. Smith’s father brought the book to annual reunions for veterans who served on the USS Bennington, and began to collect signatures.

“They would sign them with their rank at the time, the raids they were on, and when they served,” Smith says. “And one day when he was 79, he said to me: ‘One of the signatures that I’d really like to have in this book is the president’s signature.’ And I thought, good luck with that.

“But I had a conversation with a friend and we got an entrée to send the book to Houston, and the president signed it,” Smith says. “And all of a sudden the whole notion of getting serious about collecting and deciding what to collect became important.”

Around the same time, Smith’s father gave him a diary he’d kept while aboard the carrier. “One of the threads I started to pull from this diary was first-person accounts,” Smith says. “First-person accounts for historians are gold.”

Smith refined his search to World War II and its leaders. “I’m sort of focused, but in a lot of ways it’s about the chase,” he says. “So, it’s a passion for the subject matter; it’s a passion for the physical book; it’s a passion for the search and the chase.” And there’s comfort to be found in the written histories of great world leaders.

“I think it’s so important to know our history; it helps a lot of stuff make sense, he says.” “That’s my homily for today: Read some history. It’ll help you be a better citizen, help you make better judgments, and help you sleep at night.”

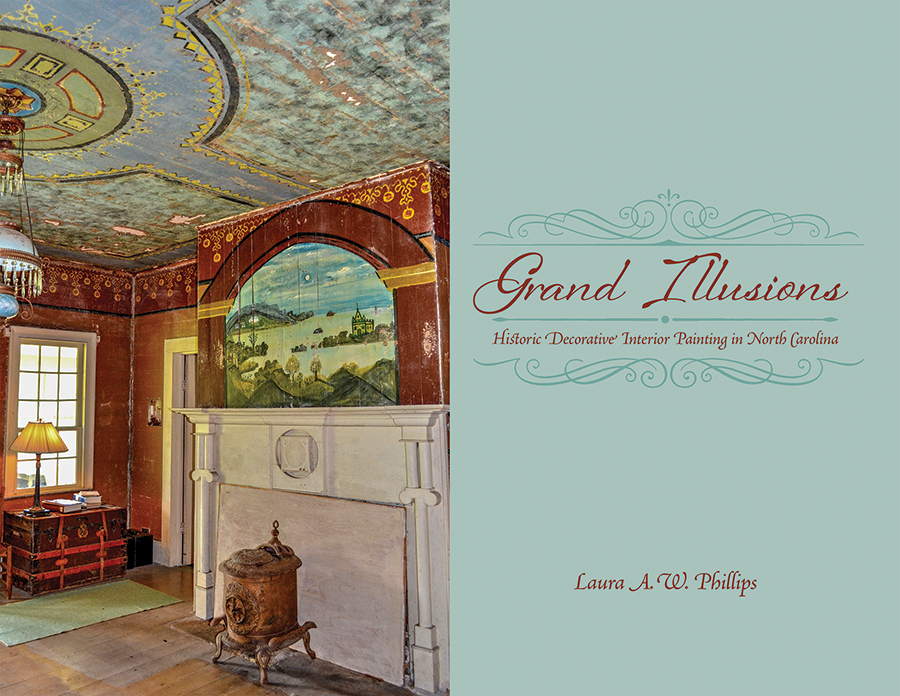

Photograph by John Koob Gessner

Mitch Capel

Mitch Capel, the alter ego of Gran’daddy Junebug, has been an impactful presence in the Sandhills for decades. Capel’s unique delivery of stories and poems — some passed down through his family, others the recited works of his favorite poet, Paul Laurence Dunbar — has enabled him to touch the lives of countless young people.

A Moore County native, Capel immersed himself in North Carolina’s artistic community throughout his storytelling career and formed close relationships with several influential artists native to the state. He and his wife, Pat, have created a collection of paintings featuring artists like Ernie Barnes, Bill Pinkney and Willie Nash.

Capel is hard-pressed to pick a favorite. “They’re like children; I don’t know. If I had to pick one it’d be my wife’s work, of course. It’d be that one with the buttons,” Capel says, referring to a portrait hanging above the fireplace in his study. In it Capel is wearing his storytelling garb, an outfit smattered by colorful buttons he has collected over the years.

Hundreds of paintings adorn the walls of the Capels’ home, including several of Pat’s alongside others by Barnes and Pinkney. “My wife and I gravitate toward Ernie Barnes,” Capel says. “He’s an amazing artist. Grew up in what was called ‘The Bottom’ in Durham.”

Barnes attended North Carolina Central University, where he played football and majored in art. He played football professionally for five years before shifting his focus entirely to art. His 1970 painting The Sugar Shack was featured in the opening sequence of the Good Times television show, and was also used by Marvin Gaye as an album cover for his 1976 album, I Want You.

“I liked Ernie Barnes’ work in the beginning because of Marvin Gaye’s album cover,” Capel says. “Album covers were our artwork at the time.”

Pinkney is another artist featured prominently in the Capels’ collection. He discovered Pinkney while performing at an alternative school in Fayetteville. After seeing his work hanging in the principal’s office, he knew he had to meet him.

“I mean, he was so talented; what he did was amazing with the paintbrush, and it came so easy for him,” Capel says.

Pinkney is best known for his painting of Julian Abele, the architect who designed Duke University’s Chapel. The work currently hangs in the University’s Gothic Reading Room.

A Bill Pinkney piece titled Marbles is especially meaningful to Capel.

“I had just unpacked this board game Mancala, and I’m on the floor and I’ve got these in my hand, and I flashed back to when I was a kid playing marbles. And the phone rings and it’s Bill: ‘Mitch, I just finished this painting, you’re gonna love it, it’s called Marbles.’ I dropped everything I was doing and went over there and I bought that piece,” Capel says.

“Yeah, it’s been a wonderful journey for me.”

Photograph by Lisa Gessner

John Koob Gessner

“In this day and age, it’s like everyone wants everything right away,” says John Koob Gessner, who thinks his collection of vinyl records represents a simpler, more intentional period of musical enjoyment. “This kind of hearkens back to a time when it’s OK to slow down and enjoy something.”

Gessner grew up in a small town in New York, influenced by his parents’ musical tastes. “Oh, yes, there was a large hi-fi, not a stereo, right outside my room. At night they would play Harry Belafonte, the big bands, Glenn Miller, all that kind of stuff. And it would kind of boom through the house,” he says.

At first, acquiring records wasn’t about building a collection, it was simply the way music was enjoyed. “If you went to someone’s house, you’d bring a couple albums with you, because everyone had a hi-fi,” says Gessner. “Records were kind of how you shared music. If someone wanted to hear a song, you had to either hear it on the radio or buy the album.”

Despite MP3 downloads and music streaming, Gessner still prefers the old-school method. “People have this affinity for vinyl. It’s analog and there’s a process to it,” Gessner says. Soon enough the preferences of his parents were supplanted by his own taste. “I was listening since I was 5 or 6. As soon as I got a paper route all my money went to film and vinyl,” Gessner says of his twin pursuits of photography and records. “I’ve been collecting ever since.”

Gessner developed a close relationship with the owner of the local record store. “I would go in and they would put stuff away for me. When I had enough money, I’d go get it.” Sometimes it was as if they could read his mind, like the time he was anxious to get his hands on John Lennon’s Christmas song, pressed on a special green vinyl. “I remember coming off a bus and stading in front of the music store and looking on a rack and they were all gone, and Mr. Nagy said, ‘Ah, Mr. Gessner, I saved one out for ya.’ And I still have it.”

His collection has grown to an estimated 4,000 records, with about half on display in repurposed bookshelves in his living room.

His musical interests created unique, career-altering opportunities. As a young photographer, Gessner shot album covers for many of the bands he listened to and saw in concert, and has kept in touch with many of them.

He continues to nourish his love for vinyl through what he calls the Vinyl Record Project. “I interview people about their experience with vinyl, and I take a portrait,” Gessner says. “They have these great wired-in memories about vinyl because you’re taking it off the rack and you’re putting it on the turntable — it’s a process.”

Photograph by John Koob Gessner

Jane and Jim Lewis

Jane and Jim Lewis are not collectors. They are self-described “accumulators.” Although they did not personally acquire the 280 unique mini liquor bottles on display in their home, they have nevertheless taken on the role as stewards of the collection.

“We’ve drug it around from place to place and displayed it, but we’ve never been collectors,” Jim says, “It’s not like we’ve been looking for them high and low for the last 50 years and we’ve worked hard and traveled the world to find them — it ain’t true.”

The mini bottles were collected by Jane’s aunt, Billie Cave, who began collecting the bottles in the late 1930s. Knowing she was passionate about collecting mini bottles, Aunt Billie’s friends acquired many of the liquor bottles as souvenirs while traveling.

“Now, back in those days her aunt didn’t travel all that much, but her friends knew about her collection and would bring her bottles,” Jim says. “People immediately assume they came off airplanes, but in fact, a lot of people got them off trains.”

While Jane and Jim shy away from the term collector, they are clearly very fond of the collection. After nearly 40 years and after each of 14 address changes, the Lewises have always unpacked the bottles for display. At their home in Pinehurst, the bottles sit on shallow shelves over a small built-in bar, a colorful centerpiece of the room, drawing the eye of visitors entering through a side door.

“The bar is here so it just made sense, and people always want to know about the bottles,” Jane says. “It’s the first thing they see.”

The bottles come in every shape and size imaginable, and the faded neon mosaic framed by the white wall is a striking mainstay of their home’s décor. A glance will not do.

Some are easily recognizable as miniature versions of full-size liquor bottles. They tend to be more dignified and expensive Scotches, whiskeys and bourbons. Others are creative and delightfully original one-offs. Exotic liqueurs and rums seem to be the most outlandish, and the Portuguese Mobana Crème de Banana in the shape of a monkey is truly a work of art.

The bottles are all unopened, although the contents of the oldest bottles have almost completely evaporated through the ancient but intact seals. Keeping the bottles in their unopened state was no easy task in a house with two young boys. As any parent whose liquor cabinet has been raided will understand, Jane and Jim told their sons a white lie to ensure the bottles remained sealed.

“When our boys were old enough to realize what it was, we told them they were poison because they were so old,” Jane says. “We told them: ‘Don’t you dare open one and drink it, because it will kill you!’ And you know they thought that up through college.”

The bottles have survived time, adolescent boys and a lifetime on the move. One day they’ll pass Aunt Billie’s bottles along to the next generation of stewards.

Photograph by Tim Sayer

Joe Vaughn

Joe Vaughn began collecting Native American arrowheads as a child and has indulged his passion ever since. Vaughn is the middle child in a family of five boys, and his upbringing in Northampton County, North Carolina, afforded him endless opportunities to search for the elusive artifacts.

“As kids we hunted and fished, and part of hunting and fishing is walking across fields,” Vaughn says. “We just developed an early interest in collecting a lot of old stuff, and one of the things we collected was arrowheads.”

Over the years he’s found hundreds of perfectly intact arrowheads, all from the northeastern part of North Carolina. The best examples are still sharp to the touch. Vaughn considers the most impressive item in his collection to be a Clovis point, a longer spear point with a groove running down the middle. It is one of the oldest styles found in North Carolina and dates back to around 12,000 B.C.

“It’s so rare to find these good ones, because there’s been so many plows and things stuck in the ground. It’s hard to find them anymore,” Vaughn says.

The first step in finding fertile ground for hunting arrowheads is thinking about what the landscape provided thousands of years ago. Native Americans were more likely to settle in a spot near water, animals and edible vegetation, so sandy and loamy soil and moving water are good indicators.

“We hunted mostly on sandy fields, close to water, close to a stream, where the game is, too,” Vaughn says. “We’ve walked in thousands of fields that didn’t have anything. But when you get to one that’s got something, you know right away.”

A fruitful field may have been recently plowed and then rained on. The plowing unearths buried artifacts and the rain washes away the final layer of dirt — a lucky combination made more difficult after modern farming techniques began planting seeds with a drill.

“Normally we hunted in fields that were under cultivation. Back in the day, farmers plowed fields more often. They don’t plow them much anymore,” Vaughn says. “So, a lot of the places that we used to find arrowheads as kids are not cultivated anymore. You’re lucky if you happen to get something. Today you might go five times and find one really nice one.”

Vaughn still hunts arrowheads with his older brother, Charlie, valuing the time spent outdoors with family more than anything he could hope to find. “It’s been fun collecting these, I’ll tell you that,” Vaughn says. “Especially in the spring when the weather gets permissive, you can go out and get some exercise, enjoy the fresh air and the camaraderie.” PS

Will Harris is serving an internship at PineStraw to complete his Business Journalism undergraduate degree from the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. He works locally as a carpenter, enjoys playing tennis, sailing and spending time with his dog Bear.