The collected letters of an American hero

By Bill Case

Right Photo: Lt. Alexandre Stillman, bottom row middle

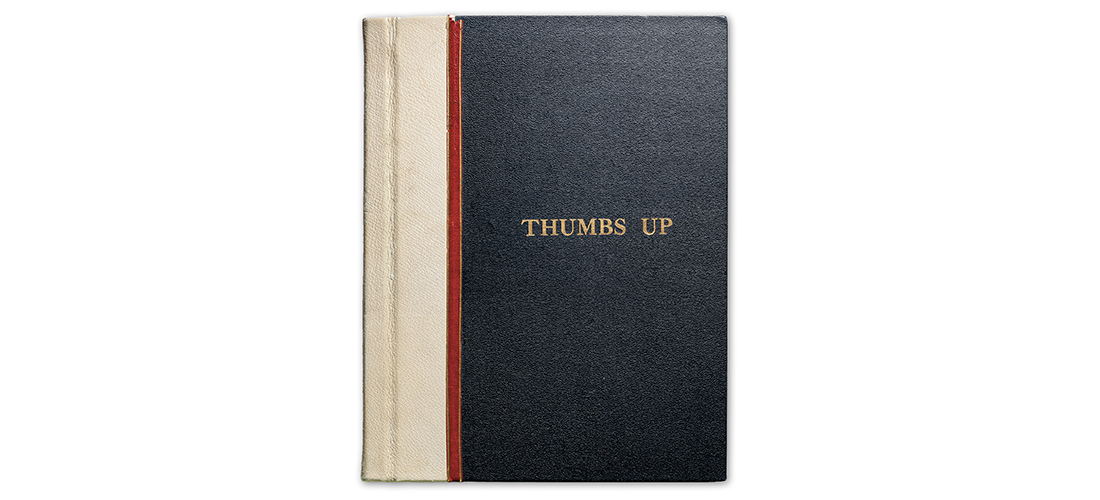

Last July an unidentified patron entered Pinehurst’s Given Tufts Bookshop, went to the rear of the building and placed a bound volume at the shop’s drop-off table for donated books. Tightly bound with a black, white and red-trimmed cover, the volume’s outward appearance didn’t raise any eyebrows. Curiously, though, its title, Thumbs Up, was not accompanied by any identification of the author.

Before donated materials can reach the shelves for resale, shop manager Jessica Flynn inspects them. When she looked at Thumbs Up, she was both intrigued and puzzled. Far from a traditional book, the volume comprised typed letters in chronological order on 167 pages of onionskin paper, dated from 1940 to 1945. The letters had been written by a World War II Navy pilot detailing the entire sweep of his wartime service, culminating in piloting a B-24 Liberator bomber in the Aleutian Islands and then in unidentified locations in the Pacific theater as he flew missions off the coast of Japan.

Who this pilot was, however, was not altogether clear. None of the letters in Thumbs Up are signed, suggesting the onionskins are carbon copies of originals. One letter, roughly halfway through the book, left a space for a signature and underneath it the words “Lt. A. Stillman — officer in charge, Air Operations.” In another letter sent to the author’s mother, he expresses satisfaction that a newborn relative had been named after him: “Jean Joseph Alexandre.” Could the “A” in “A. Stillman” stand for Alexander?

The volume also contained several pasted-in pen and ink drawings and photographs, including one of the pilot and his crew. It was clear that Thumbs Up was a one-of-a-kind historical document worthy of preservation. Perhaps a family member — if one could be found — would treasure this collection from the front lines of the air battle in the Pacific. But first a positive ID had to be nailed down.

Initial inquiries on U.S. Navy websites turned up nothing pertaining to an A. Stillman, pilot of a B-24 Liberator in the Aleutians and the Pacific. Though dubious that a mere Google search of “Alexander Stillman” would produce any useful information, I went through the motions anyway. On the “Find a Grave” website, I discovered a studio portrait of someone named Alexander Stillman in fully decorated military uniform. The confident-looking, mustachioed officer in the picture bore an uncanny resemblance to a young Ernest Hemingway. The website said this Alexander Stillman was born in 1911 and died in 1984. He would have been 29 to 34 years of age during the period when the Thumbs Up letters were written, a good fit. But was the man in the online photograph and the author of the letters one and the same?

In the pilot’s squadron photo on the first page of Thumbs Up, the man kneeling in the middle of the first row was a smiling mustachioed officer. It was undoubtedly the same man.

Alexander Stillman, it seemed, was the author-pilot, and furthermore, I now had two pictures of him. But, aside from birth and death dates, I knew little else about the man. It was time to chase Alexander Stillman to the end of the internet. Googling on, I located the website of the Stillman Nature Center in South Barrington, Illinois, outside Chicago. The SNC is described as “a private, nonprofit center for environmental education, located on 80 acres of woods, lake, and prairie.” Many birds of prey, including grey owls, populate the preserve. Alexander Stillman, who lived on Penny Road in South Barrington, had donated the land.

The fact that Stillman had the kind of money that would allow him to donate a large tract of valuable acreage to charity suggests a man of independent and rather significant means. And he was. His father, James A. Stillman, it turns out, was the chairman of National City Bank of New York, and the holder of a vast family fortune. In 1901, James married Anne “Fifi” Urquhart Potter. The couple had four children: Anne, Bud, Alexander and Guy (who, like Alexander, was a wartime lieutenant in the Navy). In 1921, James and Fifi became embroiled in a divorce fit for the salacious Page Six of the New York Post — if such a thing existed then — involving charges and countercharges of infidelity. News of the contentious court filings was reported nationwide.

The couple reconciled for a time but the marriage finally ended in 1931. After her divorce was finalized, Fifi again became the subject of national gossip when she married Fowler McCormick, a man 20 years her junior, who was heir to the International Harvester fortune. Fowler had previously been Fifi’s son Bud’s roommate at Princeton University.

A short biography of Stillman on the nature center’s website, researched and written by a one-time student intern named Helen Reinold, praised Stillman’s advocacy for environmental causes, in honor of which he received a Certificate of Life Membership from the National Audubon Society. Though Reinold didn’t, it would seem, have any knowledge of Stillman’s World War II correspondence, she does mention a letter he wrote to his sister-in-law, Guy’s wife, about his grandmother, a famous stage actress named Cora Brown Potter. In the letter Stillman writes of his grandmother that “she had abandoned her only child in order to flee her very dull marriage to Grandfather, going to London to pursue her career as an actress . . . the Toast of London, being so it was inevitable that she should meet the Prince of Wales. The Prince of Wales, later Edward VII, had very little to do except change his clothes four times a day, overeat and drink, of which he died of, and court the most beautiful women of his day. Inevitably Grandmother became his mistress of a long line, but she was one of the last three and to whom he was longest faithful.”

Reinold goes on to detail Stillman’s penchant for international travel. The countries stamped into his passports included France, Colombia, Honduras, Nicaragua, Guatemala, Peru, Brazil, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Venezuela, Panama, Ecuador, Egypt, France, Hong Kong, Thailand, Cambodia, India, Denmark and the Bahamas. And, of course, she highlights his heroic military service. “Over the course of three attacks in May and June of 1945,” she writes, “Stillman is credited with the sinking of four enemy Merchant Vessels, two large fishing boats, and a Whale Killer. In addition, he tracked an enemy cruiser and warded off attacks by an enemy plane.” She notes that he received a number of medals and commendations, at least one of which Stillman, himself, describes in Thumbs Up.

VPB 102

1 August 1945

Ma, Bow, Meme and Lou

The night before I broke out a clean khaki shirt, a pair of pants, a cap cover. My shoes were mildewed, twisted and sorry. I put a crease in the pants, wiped the dust off my hat and went to town on the shoes.

Coming down at 9.30 a bit rocky (the boys had broken several bottles over my head the night before and they were still rumbling inside) to the Squadron, I find all the PCCs out of their sack, and the pilots, and the men. My men look beautiful in clean work clothes and bran [sic] white hats. God knows where they got them.

The Skipper says “well, come on” and we stream out and straggle up the blazing sunshine between the tens of planes lined up on the white white coral.

We line up. Under the prop of a plane, and the rest wheel, and face us. A Commander comes out and tells us we can smoke a cigarette. Three of us start and then throw them away. It’s very hot.

The Admiral drives up and walks in front of us.

I stand at attention in front of him; I listen to the citation, look at his stars and my gaze wanders over his head and down between the rows of silent planes resting on the coral “and while attacked by a twin-engine fighter’s” tired planes with holes, controls shot out “sinking a third ship”, engines to be changed but we have no engines, fix and fly “and for extraordinary heroism.”

Dismiss.

If Alexander Stillman enjoyed a certain level of comfort after the war, during it he endured the same deprivations as every other soldier, sailor or Marine. In Thumbs Up, which begins with a letter to his mother written on August 1, 1940, and finishes with a letter dated 13 July 1945 from “somewhere in the Pacific” written on an aircraft carrier headed home, Stillman doesn’t exactly complain about the grueling hours, horrible conditions and continual dangers, but he doesn’t sugarcoat them either. In his July 19, 1945 letter to stepfather Fowler McCormick, he writes:

“One day I fly 13, 14, 15 hours. Next day I work on the planes. And the next we fly. . . . Have you ever done anything where you sang all the time? This is death, destruction, and hell. We have poor food, no heat, no fresh water. We live 30 people to 40 ft; we have air raids, and we average 5 hours sleep a night. Yet, I do.”

In August of 1944, when Stillman was in Kansas training on his Liberator, he writes to a woman who has professed her affection for him, fatalistically cautioning her:

“You have falled [sic] in love with a flyer and it is perhaps not a good thing. We don’t live in the past and now in our third year of war soon to go out again, we are on borrowed time. Do you realize?”

In addition to the photographs and numerous pen and ink drawings, the book includes the occasional bit of verse. To make his point that the flying conditions in the Aleutians are invariably poor and risky, in June of 1943 he cites “an Alaskan nursery jingle”:

There are bold Alaskan pilots

And there are old Alaskan pilots

But there are no old bold Alaskan pilots.

After 69 missions over Japan, flown from Tinian and Iwo Jima, and numerous others in the Aleutians, the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki brought an end to the war with Japan. On an aircraft carrier bound for home Stillman wrote:

All today over the roaring radio we have listened to crowds in New York, Atlanta, Hollywood, Cleveland going wild. It seems to make us more quiet in the wardroom. Perhaps we remember but don’t want to, the rows of white crosses, the burials we had, the useless searches in acres of ocean, the lousy chow, the brass, the impossible flights, coming in on 40 gals. of gas and will. One lieutenant for the second time on good record, all fair, said “Don’t you feel let down?” I agreed.

And he finishes:

Tonight a carrier takes us home, Eve 91, over the blue and bloody waters, eastward, to the dawn of tomorrow.

I spoke to two of Alexander’s nieces, Alexandra (“Alex”) Stillman, of Alcata, California, and Sharee Brookhart, of Phoenix, Arizona. They remembered their uncle, whom they called Aleck, as a tall, lanky, handsome man who never married or fathered children. They recalled that their father, Aleck’s brother Guy, once confided that Alexander had flown so many missions during the war that many in his squadron feared going up in the air with him, worried Stillman’s “number” had to be coming up soon.

The two sisters thought that perhaps their uncle’s wartime service in the Pacific may well have been the high point of his interesting life. He chose a military funeral in Honolulu at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific. His interment was accompanied by a 21-gun salute.

Whether it’s serendipity or destiny, two of Alexandra’s granddaughters attended Chapman University in Orange, California. Chapman is the home of the Center for American War Letters Archive, something that grew out of the “Legacy Project” begun by Andrew Carroll.

“Just about every aspect of World War II has been written about,” says Andrew Harman, the collection’s archivist. “What we’re trying to dive into now is the mundane, the individual aspects, the experiences that people were writing about in the first person at the time. Our mission is to preserve but, being a part of Chapman University and an academic library, we’re very big on access and research. It’s a room full of white pages if no one is looking at them.”

The Given Tufts bookstore has donated Stillman’s collection to the Center for American War Letters.

The mystery of the identity of the author of Thumbs Up has been solved, and Stillman’s letters now reside in an appropriate home. But who had delivered this fascinating volume to a used bookstore in Pinehurst and why? That, we may never know, but we’re glad they did. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.