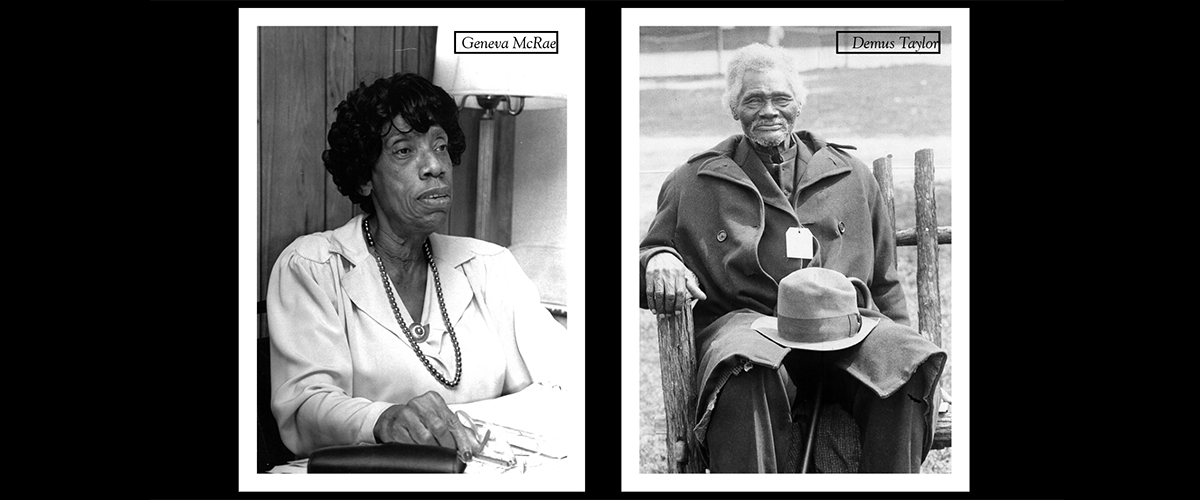

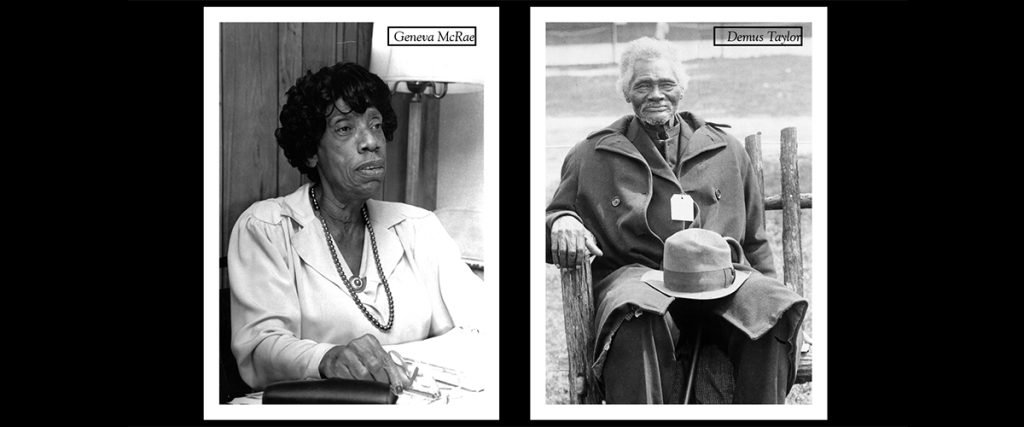

Geneva McRae, Demus Taylor and Taylortown

By Bill Case

Having been gone so long she couldn’t remember when she left, Geneva McRae decided it was time to come home to Taylortown — the African American community of 650 souls where she had spent her formative years. Decades before, the untimely death of Geneva’s father, Charlie, caused her mother, Lowverta McRae, to relocate from Taylortown to New York City along with her six children. Lowverta sensed her kids stood a better chance of advancing their fortunes up north rather than in the Sandhills, where employment opportunities for Blacks were mostly limited to low-paying service jobs with the Pinehurst resort.

For the energetic and adventurous Geneva, New York proved a godsend. She would thrive there during a remarkable career in public service. First, she served a three-year hitch in the U.S. Army that featured culturally broadening deployments in England, France, and Germany. Following her discharge, McRae attended night school at City College of New York where she received a degree in education. While taking graduate studies in public administration at NYU, she taught at a city elementary school.

After passing a civil service examination she was hired by the New York State Employment Service where she steadily rose through the ranks holding management positions of ever-increasing responsibility, including the supervision of the agency’s first Job Corps unit. Her success caused a sister public entity to come calling. She took a two-year leave of absence to run South Bronx’s “Hunt’s Point” program for job training and health needs.

Shortly thereafter, McRae was recruited to serve as deputy director of New York City’s Model Cities Program. In that role, she helped underprivileged women receive the training necessary to become nurses. She also administered programs providing medical internships for minority candidates. “That’s where I got my education — my baptismal if you will — in community work,” McRae told The Pilot staff writer Huntley Womick in a 1990s interview.

Given her well-developed social network, McRae’s friends assumed she would remain in New York after retiring in 1978 at age 63. But the Sandhills called her home. She owned a tract of land in Taylortown — left to her by Lowverta — who instructed her daughter to never sell it. McRae built a house on the property and, when it was completed in 1982, she moved in. Her roots in Taylortown, however, stretched well beyond her ownership of land.

“Our forefathers, mine included, founded this community in the early 1900s, and built homes and churches,” she told The Pilot. The founders left “a pioneering spirit that continues to live in the hearts of the people.”

Demus Taylor

Taylortown’s strong religious ethos also attracted McRae. She expressed pride that the town’s people are “taught to love God and love the community.” Throughout its history, Taylortown has been home to an array of vibrant, well-attended churches including House of Prayer, Galilee Baptist, Spruill Temple Church of God, and Spaulding Chapel AME Zion. Geneva became a devout member of the latter, serving on its board of trustees.

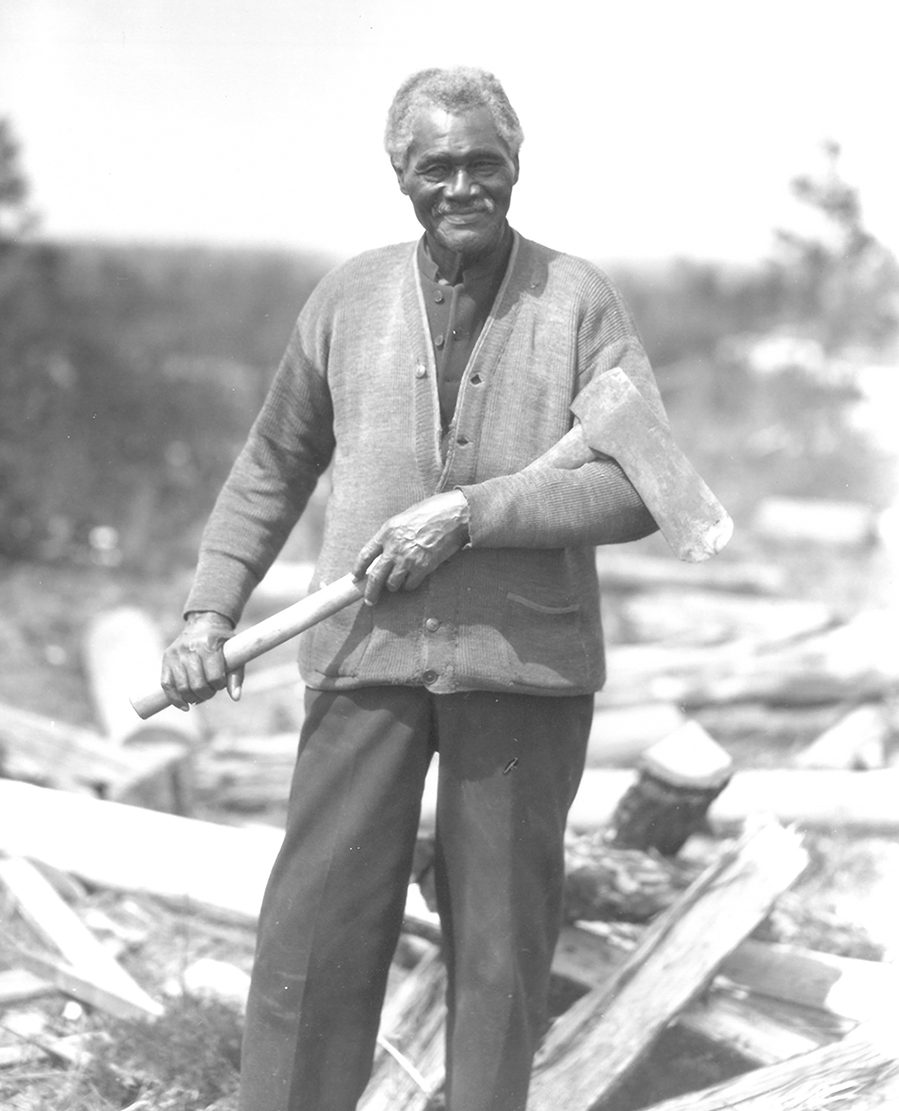

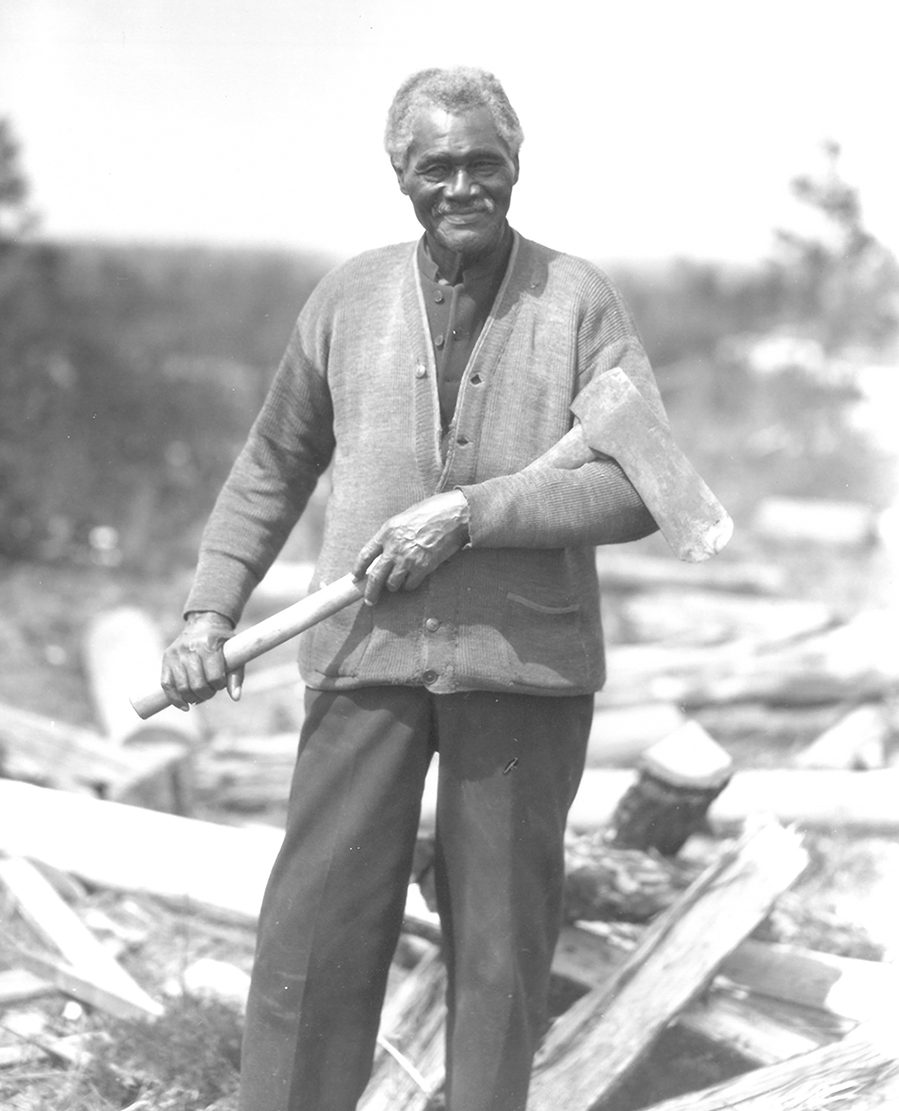

Spaulding Chapel AME Zion had also been the chosen church of the town’s founder Demus Taylor — at 6 feet 5 inches, a larger than life figure. He was born into slavery, perhaps as early as 1821, though the exact date is unknown. His ancestors were from the West African Ebu tribe. Among Demus’ “owners” was James Taylor, brother of the 12th U.S. President, Zachary Taylor. According to one account, Demus’ ownership changed hands five times before his emancipation. After gaining his freedom — and the ability to trade his labor for wages — he worked in the turpentine trade, notching trees at a nickel apiece. Like Paul Bunyan, the lean, powerful Taylor could do the work of three men, notching hundreds of trees daily with his trademark axe. Apparently Demus was too productive for his own good. His employer determined the per tree stipend was too generous and trimmed Taylor’s compensation to a flat rate of $2 per day plus all the rations the man with the axe could eat.

When James Tufts came to Moore County in 1895 and founded Pinehurst, the aging Demus saw an opportunity for a new gig. With golf emerging as the resort’s primary attraction, Taylor (by then presumably in his mid-70s) decided to try caddying. He became a good one, often looping for Donald Ross. According to Golfdom magazine, Taylor ingratiated himself with the legendary golf professional and budding architect, becoming Ross’ “top Sergeant” at the resort’s caddie shack.

At first, Taylor and numerous Black workers resided at the “Old Settlement” — an area adjacent to what is now the 15th hole of the No. 3 golf course. Around 1905, Taylor bought property from Tufts located across current Route 211. Like a latter-day Moses, he led a migration of Black workers to this land, initially referred to as the “New Settlement.” Eventually, the transplanted residents began calling the area Taylortown, a fitting tribute to Demus.

Taylor died in 1934 and the stories reporting his demise gave a range of his age from 106 to 113. Numerous Taylortown men would follow Demus’ example by caddying at the resort including Hall of Fame loopers Robert “Hardrock” Robinson, Willie McRae (unrelated to Geneva), and Sam Snead’s man, Jimmy Steed. Over the years, the community would become home to scores of other resort employees: maids, laundry workers, masons, and laborers. Robert Taylor, Demus’ son, founded a school for Taylortown children. And, before moving to New York City, Geneva McRae graduated from that institution — the Academy Heights High School.

When McRae returned to Taylortown in 1982, she discovered her New York-honed community service skills were in high demand. In 1984, she joined the five-member board of the Taylortown Sanitary District, an entity founded in 1963 for the purpose of providing the first water service and streetlights for the town. She was elected chairperson of the board in 1985.

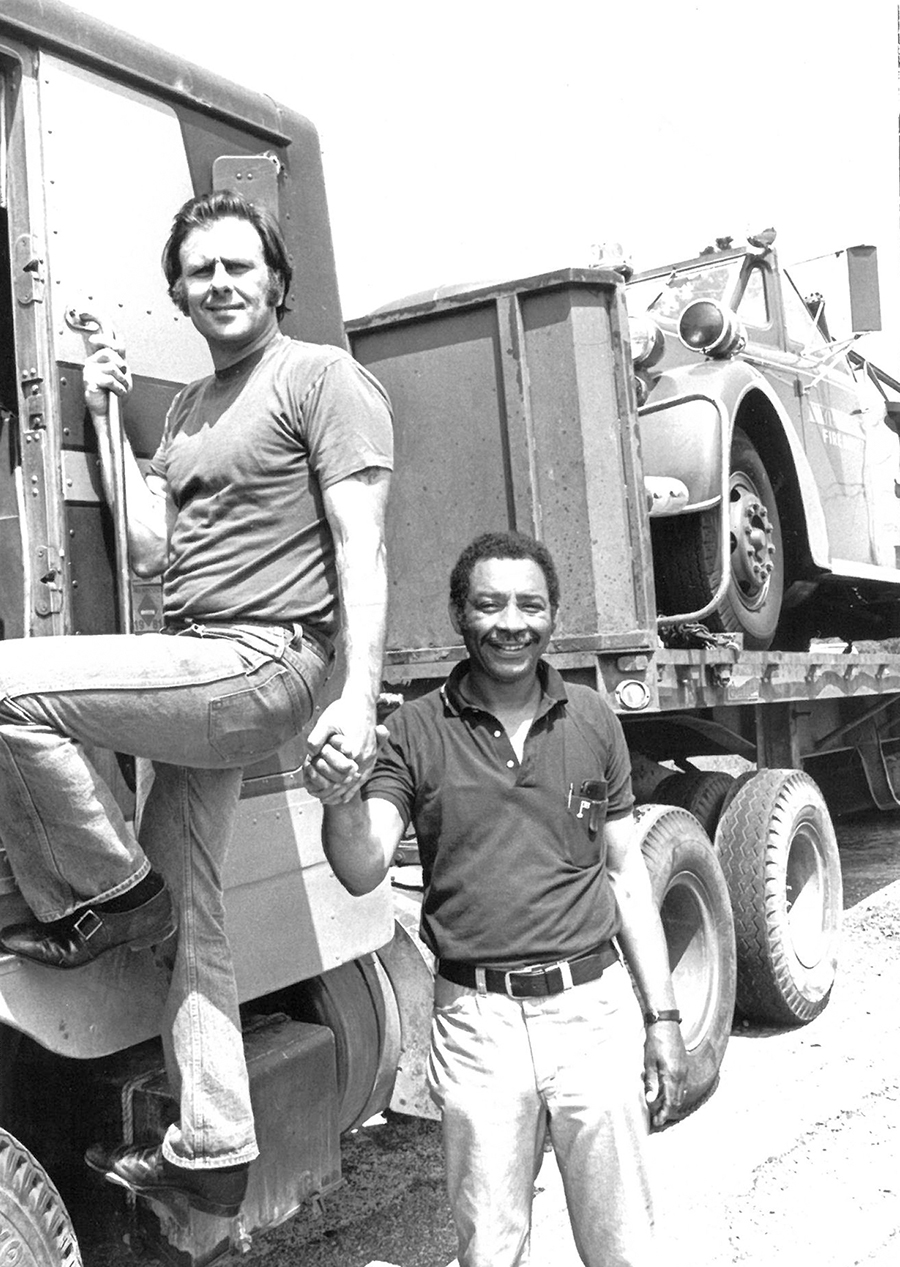

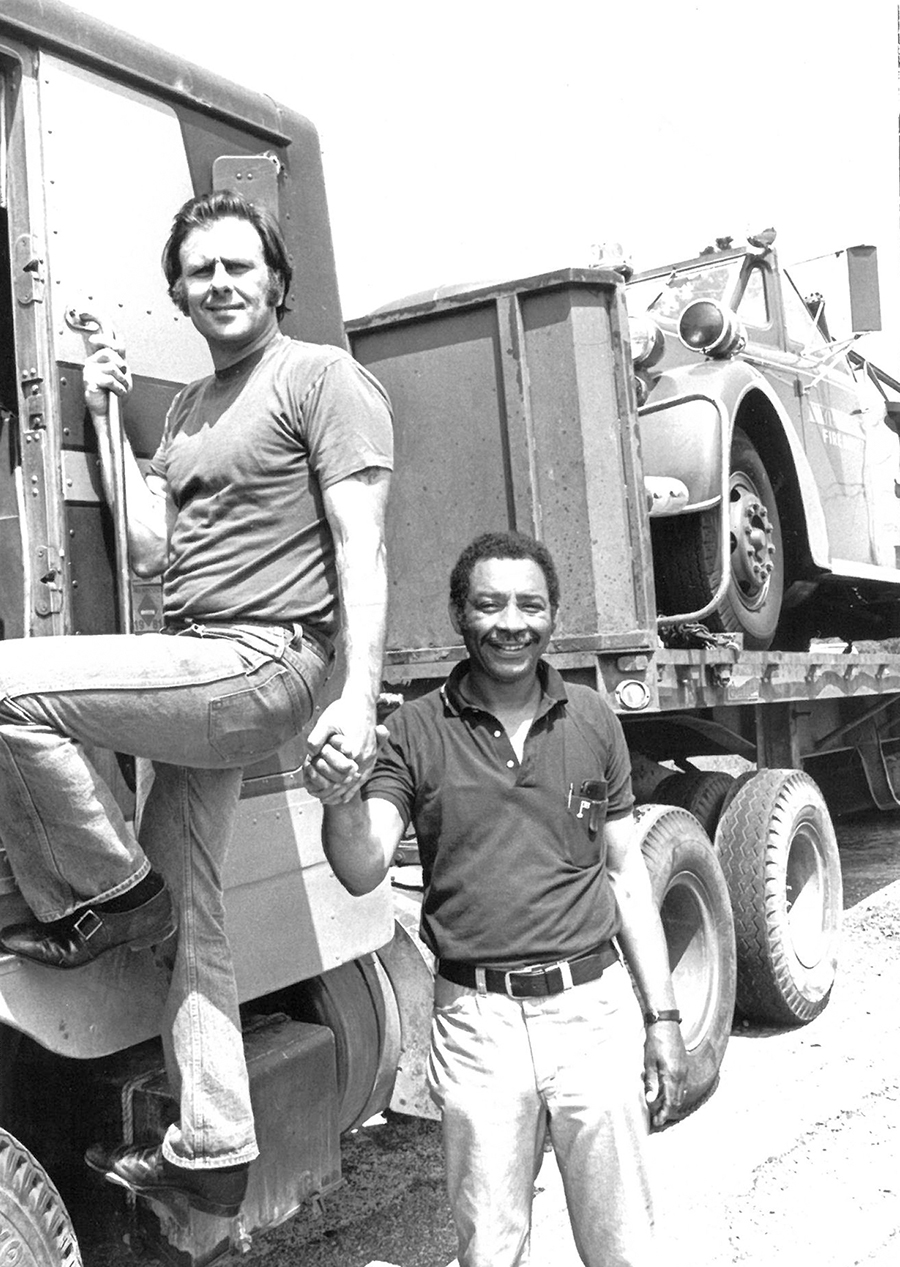

In 1981 J.O. Quin and Perry Barrett haul a ladder truck to Taylortown.

In 1981 J.O. Quin and Perry Barrett haul a ladder truck to Taylortown.

The advent of the Sanitary District marked an early step toward self-government for Taylortown’s inhabitants. Its establishment provided the necessary governmental entity to borrow money to construct the water lines and repay the loan. The Pinehurst Community Foundation pitched in to assist its Taylortown neighbors by paying for a legally required engineering study. Prior to the time the district came into being, “only six or eight houses had indoor plumbing,” according to early district board member Floyd Ray. Many residents had been forced to carry water from a pump or neighboring well to their homes for cooking, drinking, and bathing.

The Sanitary District represented real progress but residents of Taylortown hoped the time would come when the community could independently provide other governmental services. The county sheriff was primarily responsible for policing, but deputies patrolled the community sporadically at best. Far flung Moore County Emergency Services provided fire protection with additional assistance from Pinehurst. Periodic attempts to provide such services locally had failed to get off the ground.

In the 1960s, for example, community leaders urged Moore County officials to appoint a part-time deputy sheriff to patrol Taylortown. The sheriff and county commissioners were amenable to the concept but indicated the officers’ compensation would need to be borne by Taylortown residents. Had the community then possessed the status of a municipality with taxing authority, funding for the officer probably could have been arranged. But it was not, and the initiative went no further.

In 1980, former Taylortown resident Perry Barrett launched a heroic, though ultimately futile, effort to establish a local fire department in his hometown. Barrett, then a head carpenter for the Nassau County (New York) maintenance department, got wind of the fact that New York-based fire departments were jettisoning and junking a couple of their fire trucks. Perry saw an opportunity to create a fire department in Taylortown and persuaded the authorities to give him the trucks. After making repairs, he got behind the wheel of one of the pumpers and began the long journey south. The truck’s engine blew en route and an exasperated Perry was marooned alongside the highway. He eventually managed to get the trucks to North Carolina, an achievement that garnered national publicity. North Carolina governor Jim Hunt awarded Barrett the Order of the Longleaf Pine, but his exploits would go for naught. Absent municipal status, Taylortown was in no position to operate, house, or staff safety forces of any type.

Such disappointments led civic leaders to consider the possibility of incorporating Taylortown as a municipality and momentum in that direction increased after Pinehurst proposed a new planning and zoning ordinance in 1981. As a municipality, Pinehurst under state law could zone unincorporated areas located less than one mile from its boundaries, thus including much of Taylortown.

This situation annoyed town resident Ruth Jackson who expressed the frustration shared by many in her community. “Who is representing Taylortown?” she inquired at the public hearing on the zoning ordinance. “We’ve requested water, sewer, and police services from Pinehurst several times. And every time, we’re told to go to Carthage. Now you come looking for us when it’s something we don’t even want.” Jackson further noted that hearings were being scheduled on weekday afternoons when Taylortown laborers couldn’t leave work to attend.

Given her successful role as Sanitary District chair, Geneva McRae realized she would be expected to take the point in any incorporation campaign at the North Carolina legislature. So she, together with Sanitary District commissioner Micajah Wyatt, took charge. Geneva’s background in community organizing came in handy. “I’ve never worked as hard on any job and put in so many hours,” she told an interviewer. “But it [was] a labor of love.”

She and Wyatt formed the Taylortown Executive Committee which sponsored fundraising activities to pay for a survey of Taylortown’s boundaries. Next, Geneva turned her attention to the churches — familiar ground for her. She asked for and received assistance from the Ministerial Alliance, a group established in the ’70s consisting of Black ministers from Taylortown and other Moore County churches. The alliance members would prove vital to the effort. McRae also met with Raeford mayor J.K. McNeil to prepare a feasibility study to support incorporation.

In June 1986, a petition to incorporate Taylortown was submitted to the North Carolina General Assembly. State Representative James Craven of Pinebluff adopted Taylortown’s incorporation as his personal cause by introducing proposed legislation to make it a reality.

In one meeting on the bill, Pinehurst mayor Charles Grant sought to derail it, claiming that state law did not permit incorporation by a small community located within one mile of a larger one. Craven countered that the cited law only applied when the larger community had a population of at least 5,000, which Pinehurst (at the time) did not. Mayor Grant argued that incorporation would cause problems with overlapping police jurisdictions. The resourceful McRae was prepared to respond. “If police will be a problem, why does Pinehurst tell us this is not in their jurisdiction for police services?” she asked.

Rev. H.C. Johnson, a Ministerial Alliance member, also spoke in support of Taylortown’s bid for municipal status, and did so emphatically. “I don’t want Pinehurst telling us what to do. We poor folks made Pinehurst what it is. We worked for nothing, $40 a week. We made it what it is and want to leave it there.”

First village council members: Jesse Fuller, Frances Johnson, Floyd Ray, Geneva McRae and Daniel Morrison

First village council members: Jesse Fuller, Frances Johnson, Floyd Ray, Geneva McRae and Daniel Morrison

However, the opposition of Pinehurst, coupled with the fact that the General Assembly was in short session resulted in the bill going nowhere. While frustrated, McRae and other incorporation proponents were not discouraged. “We were so determined to make Taylortown a municipality that we did everything required of us and more,” she told a writer for the Citizen News-Record.

Craven’s bill was finally taken up for consideration by the General Assembly the following year. A series of legislative committee meetings on it necessitated attendance by McRae and members of the Ministerial Alliance. Bishop Larry Brown, minister at Taylortown’s House of Prayer, was among the faithful attendees. Brown estimates he made at least 25 trips to Raleigh. In a recent interview with Pilot reporter Laura Douglass, the bishop indicated that more than one opponent of Craven’s bill questioned whether a town of Black people would be able to govern themselves. But the presence and advocacy of Brown and his fellow men of the cloth gave a spiritual dignity to Taylortown’s presentation, impressing the legislators.

Eventually, Pinehurst dropped its objection to the concept of Taylortown’s incorporation, but the village remained opposed to Craven’s bill when it was amended to include within the proposed municipality three vacant parcels comprising 31 acres located on the north side of Route 211. Pinehurst was itself attempting to annex the parcels, now the Pinecroft Shopping Center that includes the Harris Teeter grocery store.

The question of which town should wind up with the 31 acres constituted the last roadblock for McRae and the other proponents of incorporation. A key Moore County state senator, Wanda Hunt, also the chairwoman of the Senate’s local government committee, was feeling pressure from both sides. She wanted to vote for Taylortown’s incorporation, but because a property owner in the disputed area (who happened to be a Hunt supporter) preferred that his property remain in Pinehurst, her vote was up in the air. Moreover, the North Carolina League of Municipalities was siding with Pinehurst. After what Craven would describe as “a lot of lobbying,” he convinced both the League and Hunt to support his bill. With them on board, the state senate unanimously approved Craven’s bill 40-0. The inclusion of the three valuable parcels within Taylortown’s corporate limits would furnish a welcome boon to the new municipality’s tax base.

On July 13, 1987, Taylortown became a municipality. As was her style, McRae gave credit to everyone but herself for the achievement but, absent her organizational skills and tenacity, incorporation likely would have remained a pipedream.

As a result of incorporation, the Sanitary District was disbanded. To run the municipality’s affairs, a five member village council was established, initially consisting of McRae, Floyd Ray, Jesse Fuller, Frances Johnson, and Daniel Morrison. The new council selected McRae to be the town’s first mayor. Described by one writer as “a willowish wisp of a woman who, nevertheless, packs a wallop,” McRae would serve two terms in the post.

Her tenure was an active one. Under her leadership, Taylortown entered into a formal fire protection agreement with Pinehurst. That arrangement continues to this day. A police department was established after the council figured it could pay an officer of its own less than it would pay in a contract for law enforcement with the county. McRae would persuade county officials to establish a voting precinct inside Taylortown. Olmsted Village was annexed into the village. The council authorized new recreational facilities and, with financial assistance from the Sandhills Garden Club (arranged by McRae), beautification of the community became a priority.

Over the years following McRae’s departure from municipal government, many other improvements have taken place within the community. A new village hall was completed in 2000. Pinecroft and Harris Teeter occupied the once heavily contested 31 acres. Government funding was obtained to update the water system and additional streetlights were installed. Today, Taylortown Museum honors Demus Taylor and other community founders like the remarkable McRae who passed away in 2008 at the age of 93. And another gain to the community occurred when Perry Barrett, once the young man who brought fire engines to Taylortown and is now in his 90s, moved — like Geneva — from New York back home, an echo of McRae’s own words: “I love Taylortown and I love its people. I wouldn’t live anywhere else. This is home.” PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.

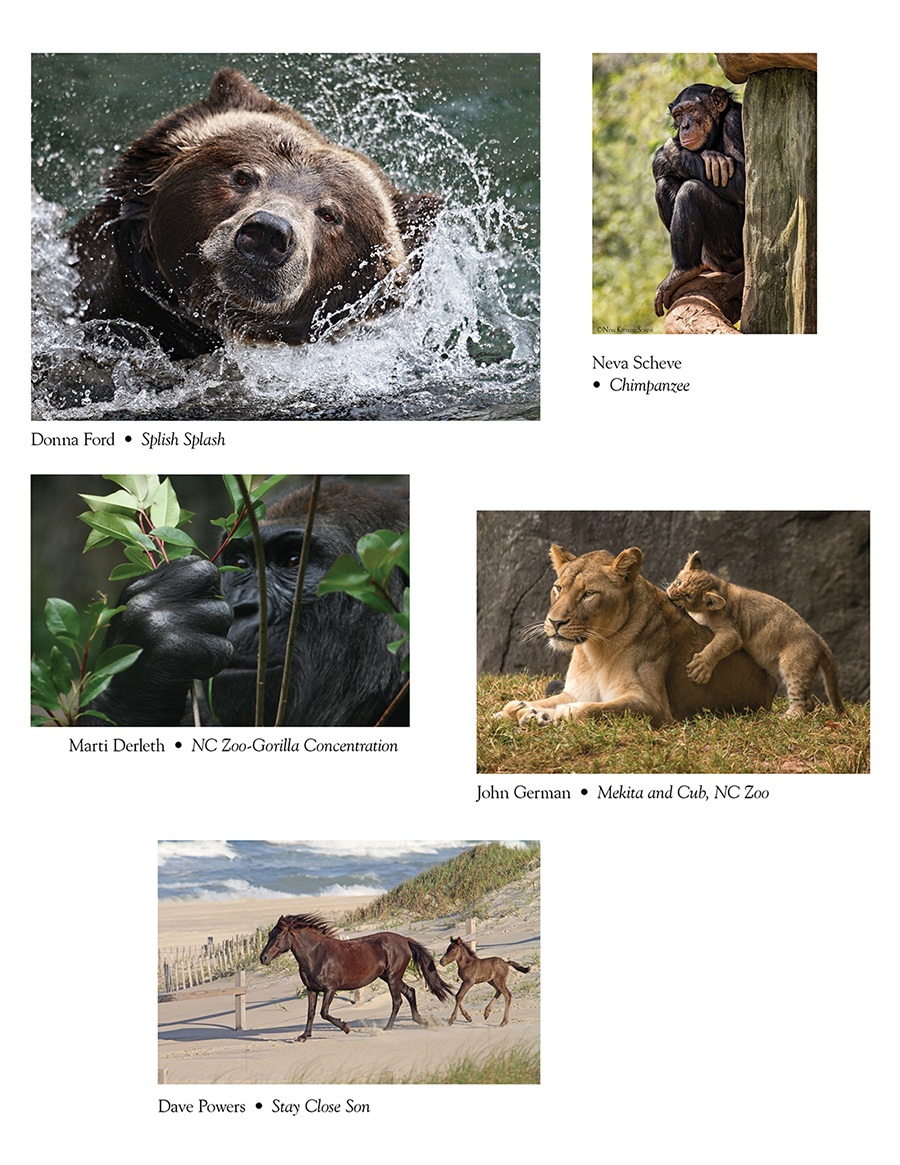

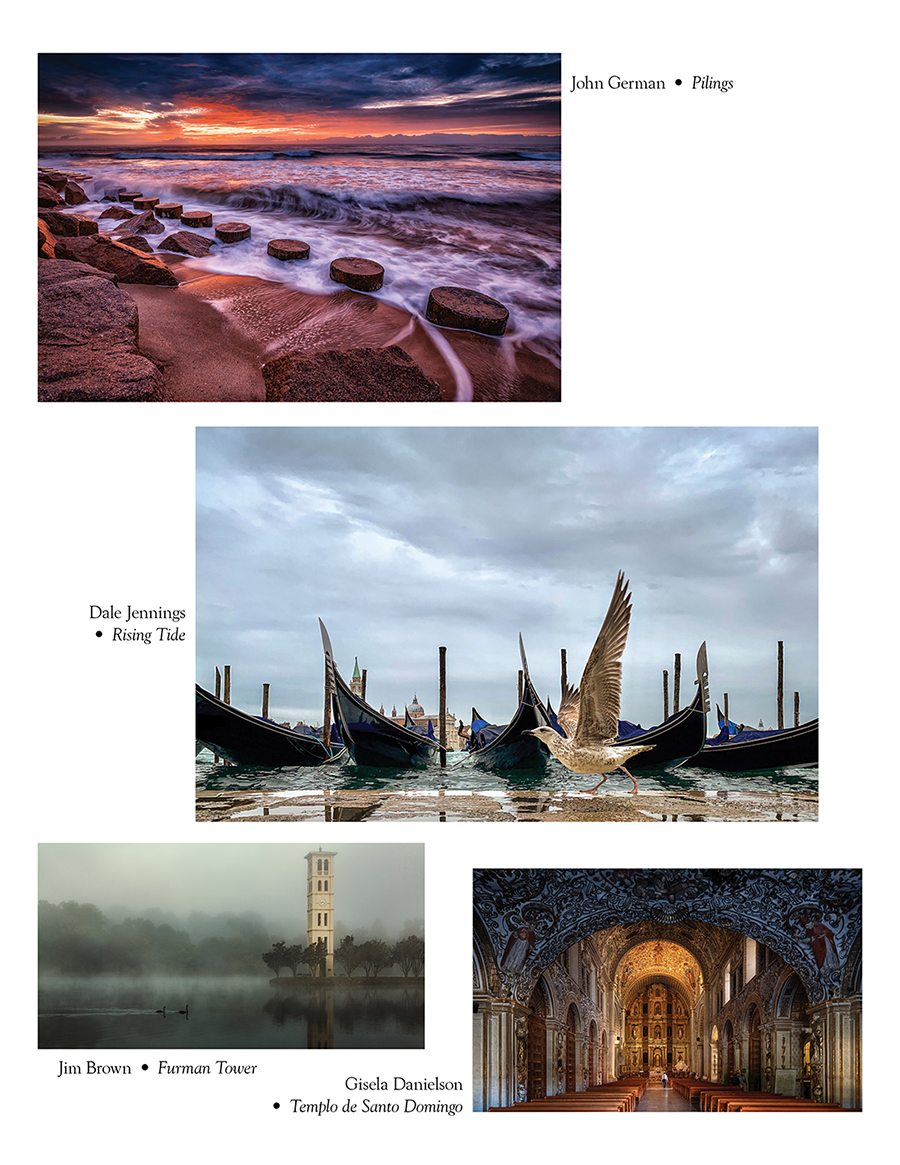

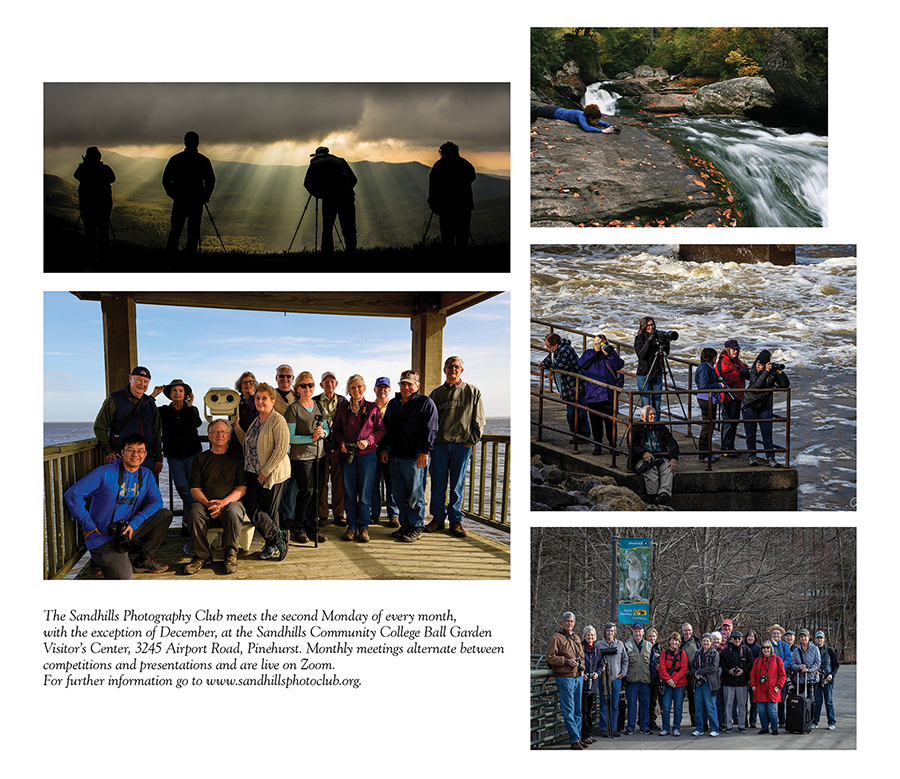

The club is also known for its two- or three-day field trips, headed up by Gary Magee, another long-standing member and a former two-term club president. This past spring the members went to Murrells Inlet, South Carolina. Other trips have taken members to the North Carolina mountains, its beaches, or even to the marshes and dunes of Amelia Island, Florida. “The idea of traveling in a group is very special,” says Magee. “We can dine together, stay at the same hotel and enjoy the beautiful gifts of living in the South.”

The club is also known for its two- or three-day field trips, headed up by Gary Magee, another long-standing member and a former two-term club president. This past spring the members went to Murrells Inlet, South Carolina. Other trips have taken members to the North Carolina mountains, its beaches, or even to the marshes and dunes of Amelia Island, Florida. “The idea of traveling in a group is very special,” says Magee. “We can dine together, stay at the same hotel and enjoy the beautiful gifts of living in the South.”

In 1981 J.O. Quin and Perry Barrett haul a ladder truck to Taylortown.

In 1981 J.O. Quin and Perry Barrett haul a ladder truck to Taylortown.

First village council members: Jesse Fuller, Frances Johnson, Floyd Ray, Geneva McRae and Daniel Morrison

First village council members: Jesse Fuller, Frances Johnson, Floyd Ray, Geneva McRae and Daniel Morrison