The Other White House

Retirement leaps out of the rocking chair, into the barn

By Deborah Salomon • Photographs by John Gessner

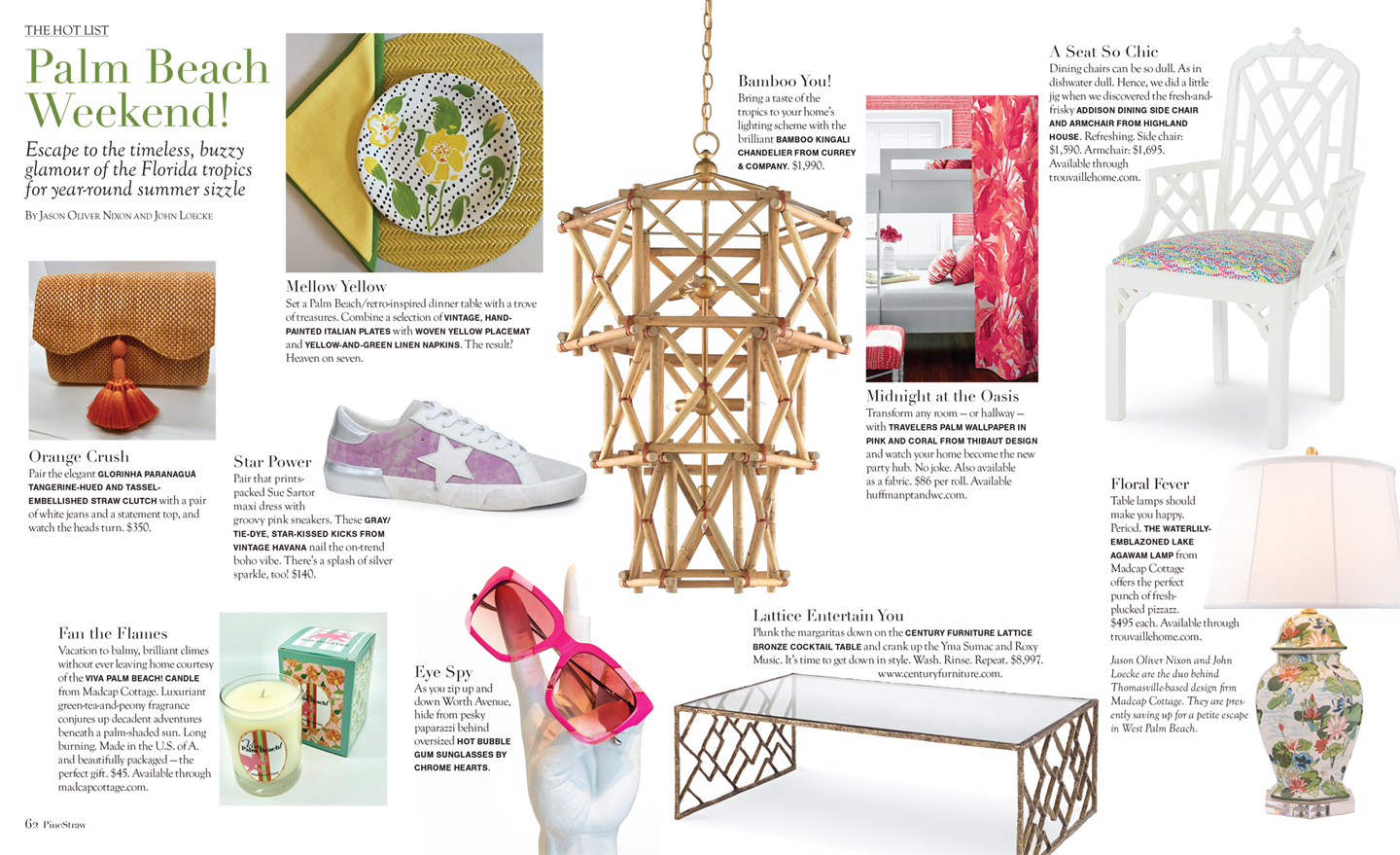

Their go-to color is a non-color, white. For Elizabeth “Boo” DeVane and her husband, Ron Gibson, this preference starts at home, where a white wooden porch swing hangs from an ancient pin oak centering the circular driveway, flanked by white gateposts.

Their white brick house on a sculpted five acres near the Pinehurst-Aberdeen line explores other possibilities: white, barely touched with green for most interior walls; hardwood floors painted glossy white; white area rugs and white upholstery. Gradually, in rooms off a “spine” hallway that runs the width of the house, pure (but never stark) white melts into vanilla, cloud, sand, latte, putty, ash and, finally, cocoa.

Even the English bulldog, Bella, continues the palette.

Beyond the white-out, in the sunroom bay stands a gleaming black baby grand, which Ron plays. Off the living room, a darkened alcove holds two 180-gallon tanks, one run by a computer, both protected from power outages by a designated generator, containing an aquarium-worthy array of tropical fish and live coral. Their plumage and movements — calming, mesmerizing.

They are Ron’s babies.

Boo’s babies decorate the landscape visible through arched, elaborately framed oversized windows — two quarter horses (one white, one tan) and young donkey twin sisters (grayish-beige and very friendly) who live in a white barn adjoining the pasture. Bella has her own grassy enclosure surrounded by a white picket fence.

However, Boo — born on Halloween, nicknamed by her brother — and Ron have not forsaken all color. They collect art . . . bold, exciting canvases in primary hues selected by Boo’s educated eye. A room at the Fayetteville Museum of Art was dedicated to her parents, collectors Jim and Betty DeVane.

Ron and Boo, handsome retirees oozing energy, lived previously in Fayetteville and Topsail Beach. He was a school psychologist and military consultant specializing in autism. Boo left North Carolina at 18, attended New York University and worked in Manhattan managing arts-related nonprofits before returning to the family business. Along the way she accumulated interior design experience implemented by friend, designer and fellow horsewoman Cathy Maready.

In retirement, Ron’s tan comes from gardening, not golf. Boo works with rescued horses. How they met and accidentally eloped to Costa Rica after a 12-week courtship resembles a 1990s date flick starring Meg Ryan and Tom Hanks.

The equestrian community drew them to Moore County, first on an isolated farm, then a too-small house in Pinehurst.

Let’s reverse the retirement trend and upsize, they decided.

“While Ron was away, I checked around to see what was out there,” Boo recalls. Tinker Bell couldn’t have found anything more perfect.

Twin Oaks Farm, as they named it, was built in 1997 by Robert Clarke, a California “architect to the stars,” for his own family. This usually bodes well for materials and originality. Clarke’s home, however, presented a mixed bag, with those top-dollar windows sited for maximum natural light but Pergo laminate floors and a small unimaginative kitchen. Fixable, Boo decided. The five overgrown acres beckoned gardener Ron. Boo envisioned two pastures and a barn, which they built after moving in. Both were fascinated with the ceilings: vaulted, angled, slanted, mansard, one with a clerestory which draws light into the white living room, another supported by a trapezoidal beam — anything but flat.

They grabbed the house in 2019 and went to work.

Up came the Pergo, down went hardwood covered with layers of glossy white paint. The story-and-a-half floorplan remained intact except for the kitchen, which Boo gutted and replaced with something from a magazine. The result, definitely not white, stands apart from Pinehurst glamour kitchens. It’s a moderately-sized galley with a worktable, no island, earth tones, clean lines and natural materials that impart an Asian aura. Countertops are marble but not tombstone white. Instead, they have a brown-grey toned leather finish, the same coloration appearing on wood cabinetry, dishwasher and refrigerator fronts. Cupboards are textured metal and frosted glass. A small coffee bar faces a smaller wine rack. No faux-farm sink, no visible breakfast bar until Ron, with a wicked smile, draws a folded flat surface from beneath the countertop, opens it out and pulls up two chairs. Just as original is a small gas fireplace sealed waist-high into a brick column — instant comfort on a chilly morning.

There’s no formal dining room, either, just a large sunroom adjacent to the kitchen, with a round hammered copper table seating eight.

Woven area rugs, upholstery and linens in the main floor master suite and guest bedroom combine pale earth tones with tiny geometrics. Several family antiques — including a secretary and drop-leaf table Boo grew up with and a guitar from Ron’s father — blend nicely with metal headboards and a reupholstered slipper chair from Ron’s mother. Fearlessly, in the hallway and master bedroom Boo added massive tables and benches fashioned from tree-trunks. Their heavily glossed knots and grains contrast to more delicate patterns and colors used throughout, including shimmering drapes in the guest bedroom, the only window with a fabric covering.

Stairs to the second floor rise from near the end of that spine hallway. Here, Boo has an office-sitting room furnished with less white and more brown, although her desk is assembled from a distressed white antique door, its frame serving as legs. She repeats the wall-enclosed gas fireplace for thermal and decorative purposes.

The upstairs bedroom, prettier than a coastal B&B, accommodates Boo’s adult children when they visit.

Boo really lets loose in the bathrooms, perhaps to compensate for original white tiles outlined in black, which she disliked. However, instead of ripping them out, she let the geometrics set a tone. One wallpaper is made from shredded newspaper while another is black curls splashed against a white background. Whimsy rules the upstairs bathroom, where black stick figures in colorful garb imitate the drawings of Paul Klee or, perhaps, Wassily Kandinsky.

As for art, all bets are off. Pale earth tones don’t apply. Brightly-hued animal subjects include a folk art pig in one bathroom, a fanciful horse head by local artist Meridith Martens in the hallway, and upstairs, a bright, cartoonish guinea hen with a story. They saw it, liked it, but it was gone when they returned to purchase it, expense be damned. Years later, guess what showed up in another gallery?

Their favorite painting is an abstract in warm Southwestern colors by Dan Namingha, a Hopi artist from New Mexico featured at the Smithsonian Institution and British Royal Collection in London.

The grounds satisfy Ron’s near-metaphysical connection to nature, developed as a backpacker in Colorado. Not only did he remove overgrown crape myrtles and Japanese pears, he grew weed-free grass from seed, which he crops closely on his riding mower. “I’m like a kid, riding along with my headphones on,” he says. Flowers are absent, except for a few perennials, always in what Ron calls “calm colors, no yellows except for daffodils.” Boxwoods are trimmed into curves, not flat-tops or angles or topiary. A small Tuscan-style garden with fountain and pergola located just outside the dining room brings greenery up close.

Ron and Boo are busy retirees who miraculously report agreement on all decisions concerning the house. Ron admits he’s happiest with a project. Next up: an aquarium store in Wilmington. Boo mucks her own barn. She wants to rehab needy racehorses. For now, she feeds the menagerie, spends time in the heated, air-conditioned gazebo-turned-tack room adjoining the barn, a veritable girl-cave filled with equestrian equipment and memorabilia that sometimes doubles as a meeting place for their Bible study group.

What’s missing? Enormous TVs plastered on multiple walls and laptops galore. “The world was a better place” before electronics took over, Ron believes. He and Boo have other toys: two horses, two donkeys, one dog, one barn cat, two aquariums, five acres, plenty to do and the strength to do it.

“This is a place of peace,” Ron says. Boo adds, “We’re going to try to keep everything standing and moving forward, including ourselves. We are blessed.” PS