August Books

FICTION

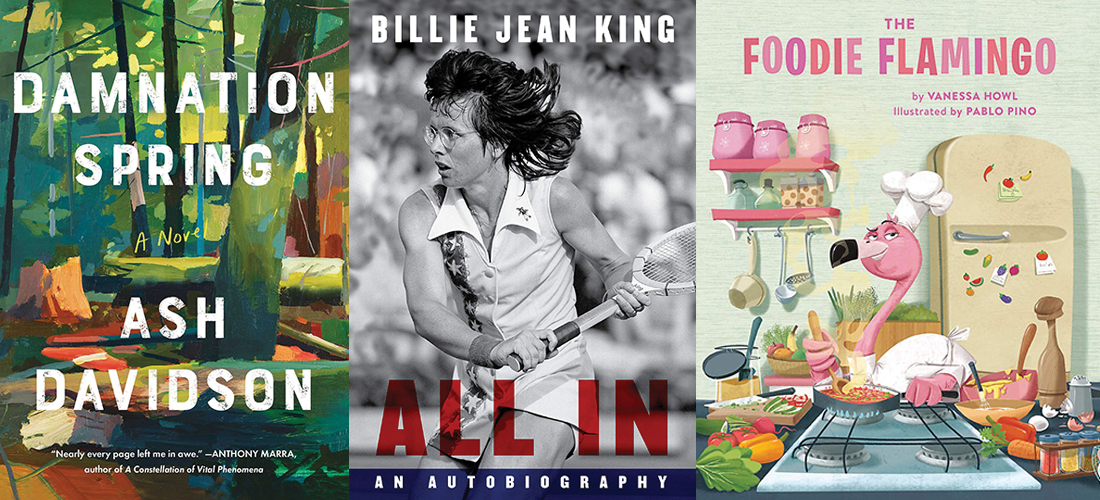

Damnation Spring, by Ash Davidson

For generations, Rich Gundersen’s family has chopped a livelihood out of the redwood forest along California’s rugged coast. Now, Rich and his wife, Colleen, are raising their own young son near Damnation Grove, a swath of ancient redwoods on which Rich’s employer, Sanderson Timber Co., plans to make a killing. For decades, the herbicides the logging company uses were considered harmless. But Colleen is no longer so sure. As mudslides take out clear-cut hillsides and salmon vanish from creeks, her search for answers threatens to divide a town that lives and dies on timber.

Once There Were Wolves, by Charlotte McConaghy

Inti Flynn arrives in Scotland with her twin sister, Aggie, to lead a team of biologists tasked with reintroducing 14 gray wolves into the remote Highlands. She hopes to heal not only the dying landscape but Aggie too, unmade by the terrible secrets that drove the sisters out of Alaska. Inti is not the woman she once was, either, changed by the harm she’s witnessed. As the wolves thrive, Inti begins to let her guard down, even opening herself up to the possibility of love. But, when a farmer is mauled to death, Inti knows where the town will lay blame. Unable to accept her wolves could be responsible, she makes a reckless decision to protect them. If the wolves didn’t make the kill, then is something more sinister at play?

Lightning Strike, by William Kent Krueger

Aurora is a small town nestled in the ancient forest alongside the shores of Minnesota’s Iron Lake. In the summer of 1963, it is the whole world to 12-year-old Cork O’Connor, its rhythms as familiar as his own heartbeat. When Cork stumbles upon the body of a man he revered hanging from a tree in an abandoned logging camp, it is the first in a series of events that cause him to question everything he took for granted about his hometown, his family and himself. Cork’s father, Liam O’Connor, is Aurora’s sheriff, and it is his job to confirm that the man’s death was the result of suicide. In the shadow of his father’s official investigation, Cork begins to look for answers on his own. Together, father and son face the ultimate test of choosing between what their heads tell them is true and what their hearts know is right.

Children of Dust, by Marlin Barton

In researching his family history in the year 2000, Seth Anderson discovers an unexpected story from the late 1800s. In 19th century rural Alabama, his relative, Melinda Anderson, struggles to give birth to her 10th child, tended by Annie Mae, a part-Choctaw midwife. When the infant dies just hours after birth, suspicion falls upon two women — Betsy, Annie Mae’s daughter and the mixed-race mistress of Melinda’s husband, Rafe; and Melinda herself, worn out by perpetual pregnancies and nurturing a dark anger toward her husband. Seeking to clear her own name, Melinda enlists the help of a conjure woman who dabbles in dark magic. Filled with haunts, new and old, Children of Dust is a novel about the relationship between two women allied against a violent man with secrets of his own.

NONFICTION

A Brief History of Motion: From the Wheel to the Car to What Comes Next, by Tom Standage

Beginning around 3500 BCE with the wheel — a device that didn’t catch on until a couple of thousand years after its invention — Standage zips through the eras of horsepower, trains and bicycles, revealing how each successive mode of transit embedded itself in the world we live in. Then, delving into the history of the automobile’s development, Standage explores the social resistance to cars and the upheaval that their widespread adoption required. Cars changed how the world was administered, laid out and policed, how it looked, sounded and smelled — and not always in the ways we might have preferred.

All In: An Autobiography, by Billie Jean King

An inspiring and intimate self-portrait of the champion of equality that encompasses her brilliant tennis career, unwavering activism, and an ongoing commitment to fairness and social justice. King recounts her groundbreaking tennis career — six years as the top-ranked woman in the world, 20 Wimbledon championships, 39 grand-slam titles, and her watershed defeat of Bobby Riggs in the famous Battle of the Sexes. She poignantly recalls the cultural backdrop of those years and the profound impact on her worldview from the women’s movement, the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy, the anti-war protests of the 1960s, the civil rights movement, and, eventually, the LGBTQ+ rights movement. She describes the myriad challenges she’s faced — entrenched sexism, an eating disorder, near financial peril after being outed — and offers insights and advice on leadership, business, activism, sports, politics, marriage equality, parenting, sexuality and love.

YOUNG ADULT

Dog Island, by Jil Johnson

Willy stared out through the crisscross wires of his cage. He had figured out a few things. One, being born a spunky beagle wasn’t always cookies and naps. Two, there was no way he was staying in this barbed wire apartment. And three, as he listened to the rows of dogs barking and howling, he wasn’t going alone. (Ages 8 and up.)

CHILDREN’S BOOKS

Becoming Vanessa, by Vanessa Brantley-Newton

That first day of school can be hard on anyone, but especially if your name is looonnng and has more than one “s” and your style is a little more colorful than your new classmates. But, no matter what, it is important to be yourself. Stunning illustrations reminiscent of the brilliant Molly Bang bring this important first-day-of-school book to life. This one is a must-have for rising kindergartners. (Ages 4-6.)

T. Rexes Can’t Tie Their Shoes, by Anna Lazowski

Baby horses can stand up. Narwhals change color. And red sea urchins can live for 200 years! But nobody can do everything. Laugh out loud with the animals of the alphabet as they show what they can and cannot do in this super-cute ABC book that is perfect for story time, bedtime or anytime. (Ages 3-7.)

The Foodie Flamingo, by Vanessa Howl

At the Pink Flamingo restaurant, it’s shrimp, shrimp, shrimp, shrimp. But when Frankie the Flamingo gets a wild feather to sample something different, she becomes Foodie Flamingo. Soon everyone is sampling new things and the Pink Flamingo will never be the same! Fun with food for all ages. (Ages 3-6.)

How To Spot a Best Friend, by Bea Birdsong

It’s easy to spot a friend, but how do you know when you’ve discovered a best friend? This sweet story is the perfect read together for the night before back-to-school or any new situation. (Ages 4-7.) PS

Compiled by Kimberly Daniels Taws and Angie Tally.

Angie’s favorite book is The Autobiography of Alice B. Tolkas by Gertrude Stein and Kimberly loves The Power of One by Bryce Courtenay.