How the Carolina Theatres of Pinehurst and Southern Pines navigated the leap from silent films to talkies in 1928

By Bill Case

he man in charge of virtually everything in Pinehurst perused the June 1928 edition of Motion Picture News, bypassing the provocative feature on the recent European vacation of Hollywood’s most glamorous couple, Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford. Instead, 32-year-old Richard Tufts concentrated his attention on the trade paper’s lengthy editorial dealing with the rapid emergence of the talking movie — a technological advancement in the film industry likely to alter the business model for movie studio and theater owners alike. One of the many hats Tufts wore in his ubiquitous management of Pinehurst was that of president of Pinehurst Theatre Company, operator of the town’s 5-year-old movie house, The Carolina Theatre, at 90 Cherokee Road.

So, on June 21, 1928, Tufts posted a letter to PTC’s general manager, Charles Picquet, expressing the view that, “Pinehurst should be one of the first to have talking movies.” Ever close with a buck, Richard focused on how the costs of retrofitting the theater to exhibit “talkies” could be minimized. With Picquet’s connections as president of the Carolina Theatre Owners Association and vice-president of the National Theatre Owners Association, Tufts thought he might avoid the estimated $11,000 cost of synchronizing for sound. To him it was product placement Roaring 20s style. “With your influence and with the recognized standing of the

Pinehurst Theatre, it might be possible for us to persuade some of the companies to locate a machine here, pretty much at their expense, in order to obtain publicity for the talking movies,” Richard suggested. Presumably his clientele, the upper crust of the East, once having experienced talking pictures in Pinehurst, would induce theater owners back home to convert to the new technology.

Picquet was the man Richard Tufts tasked with the job of keeping his resort guests and the well-heeled members of the town’s “cottage colony” entertained. Along with his wife, Juanita, Picquet had once been a member of a light opera troupe touring the U.S. and Canada. Whether it was managing the Sandhill Fair, organizing local choral groups, luring performers like humorist Will Rogers for theatrical engagements, or exhibiting feature films, Charlie was in the middle of things. He was a hands-on manager, typically greeting movie patrons wearing a tuxedo with a carnation in his lapel, then scurrying to the projection booth, changing into a blue denim jumper and running the projector. When the last frame flickered out, Picquet would be back at the theater entrance in his tux as the audience filed out.

Picquet wasted no time replying to Tuft’s suggestion, advising him events were moving at a dizzying pace. He said Paramount Pictures had already announced that “75 percent of their new product will be synchronized (talking pictures) and Metro will do the same.” Theaters in Greensboro and Raleigh were showing talkies, as were two movie houses in Charlotte. Picquet believed movie houses everywhere would inevitably have to buy in or close. Manufacturers couldn’t keep up with the demand for sound synchronization equipment, making Richard’s hope of obtaining it gratis seem as fanciful as the movies themselves. Picquet warned that addressing the issue could not be sidestepped: “We cannot escape it no matter how much we would like to.”

Since PTC was its own company, Richard Tufts and Charlie Picquet could not act unilaterally. The support of a majority of the 21 shareholders was required for such an extraordinary expenditure. Those shareholders included some glittering names in the Pinehurst galaxy: Henry C. Fownes (steel magnate and founder of Pittsburgh’s Oakmont Country Club); George T. Dunlap (founding partner of Grossett & Dunlap publishers); Leonard Tufts (Richard’s father and owner of the controlling interest in Pinehurst, Inc.); and Donald Ross (Pinehurst’s unparalleled golf course architect).

In light of Picquet’s sense of urgency, Tufts authored a message on July 16, 1928, to PTC’s shareholders asking for an immediate vote on whether to obtain sound equipment. “It is apparent to the officers of your company that the moving picture industry is about to undergo one of those revolutionary changes which new inventions frequently bring to an industry,” he wrote. Richard made the case that if the requisite synchronization equipment wasn’t put in, “. . . we shall probably lose business during the coming winter as many of our patrons will be accustomed to attending the ‘talking movies’ already installed in practically all the larger cities. We cannot afford to have this happen because we depend wholly on our winter patronage to make money.”

Since smaller theaters around Pinehurst seemed unlikely to make the move for the upcoming season, Richard was confident he’d quickly recoup the investment in box office receipts and wanted PTC to immediately initiate acquisition of the equipment. He framed the proposition this way: “If the ‘talking movies’ are with us to stay, it seems almost axiomatic that the sooner we are on the bandwagon the better off we shall be.”

Like any innovation, talking movies had its detractors. There were respected voices in the motion picture business that believed they were little more than a passing fad. Some trade journals expressed concern that the exorbitant costs of producing a sound movie made them impractical. There were fears the rehearsals necessary for actors to master dialogue would compound production costs. Not all silent stars possessed the voice and thespian skill to make a seamless transition to talkies. Other industry flacks believed the public wouldn’t accept the disappearance of silent movies’ orchestral accompaniment. And, the musicians’ union promised a battle royale to protect its members whose jobs would disappear if the talkies actually caught on. There was enough negativity bandied about to give pause to theater owners concerned about laying down serious cash for an extravagant new sound system.

With Richard Tufts on board, however, shareholder approval seemed a mere formality. He controlled enough stock by himself that he needed very little support from the non-family shareholders to get approval for his plan. The formality proved to be anything but. With an eye toward his own bottom line, J. T. Newton, holder of nine shares, was out. He was “opposed to any such expenditure that would reduce dividends.” George Dunlap ambivalently stated that while it might be necessary to “hook up” with the talking movies, his personal preference “would be the other way.” But it was H.C. Fownes’ opposition that caused Richard to waver on the proposal himself. Fownes argued the concept was only in its formative stages and questioned whether PTC was “in the proper financial condition at present to make the investment.”

Fownes’ reply to Richard had somehow caused a flip in the PTC president’s viewpoint. On July 31, Tufts wrote to Picquet, “The more I think about it, the more I think Mr. Fownes is right.” The purchase of synchronization equipment was suddenly in doubt. What caused Richard to make such a quick about-face? The answer may lie in a parallel theater-related brouhaha.

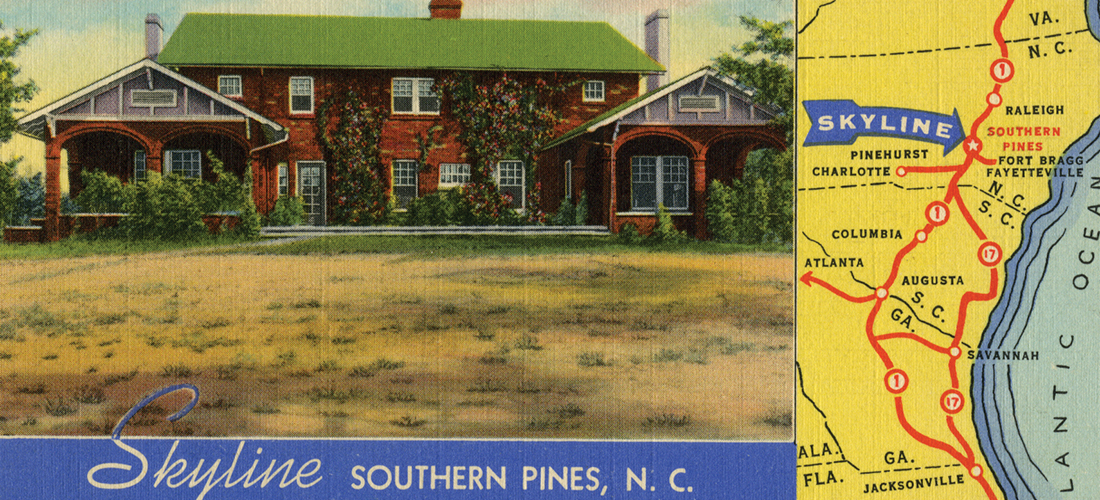

That dispute involved another movie theater operating at 143 N.E. Broad St. in Southern Pines also named the “Carolina Theatre.” PTC did not own the Carolina Theatre of Southern Pines, but Picquet and Tufts, personally, did. Though the two Carolina Theatres were not under common ownership (one owned by the PTC shareholders, the other by the Picquet/Tufts partnership), Richard considered it beneficial for them to be managed as one, giving Picquet leverage in obtaining films from distributors on terms that a single screen operator could not achieve. The two theaters could coordinate their movie showings and share the costs of a single film rental.

Earlier in 1928, Tufts and Picquet asked PTC shareholders to consider financially participating in the construction of a new theater in Southern Pines to replace the existing one, which Richard described as “a dump.” Fownes, however, rejected PTC’s participation in the construction venture outright. Richard fumed at this unanticipated roadblock and fired off an indignant missive to Fownes declaring that “it would be impossible for Mr. Picquet and me to adjust . . . if the stockholders have lost confidence in the way we have conducted the theater. It would be so much better for us to get out.”

The dust-up was resolved only after the landlord of the Southern Pines Carolina Theatre agreed to make overdue improvements. Richard usually avoided run-ins with the elite members of Pinehurst’s “cottage colony.” His atypical outburst probably caused some uneasiness in his relationship with H.C. who was arguably the most prominent cottager of all, serving on the country club’s board of governors and Pinehurst Inc.’s citizen advisory board. Fownes had personally supported a local bond issue and, after the crash of 1929, would help bail out Pinehurst, Inc. by contributing $30,000 to retire its delinquent bank note.

When the issue of PTC’s transition to talking movies arose, Tufts would naturally have been reluctant to engage in another fractious dispute with Fownes. So, when H.C. reported on Aug. 6 that a friend in the film industry had confirmed “it would be a mistake to make an investment to the degree you (Richard) estimated an outfit would cost,” Tufts did not push back. Pinehurst’s Carolina Theatre would remain a silent movie house for the duration of the resort’s 1928-29 season.

Picquet, however, was not inclined to take no for an answer. When he got wind of Fownes’ letter, he composed a diplomatic rebuttal. He informed Richard that he was “glad to see the note from Fownes also as I am anxious to hear all sides of the sound question.” However, the manager pointed out, “talkies are packing them in even during the most torrid weather while ‘silents’ are suffering and closing . . . Fox has stopped silents. Within a month Paramount and Metro will do the same . . .Within two months all newsreels will be talkies.”

Facing what he was sure would be dismal winter admissions in Pinehurst, Charlie urged reconsideration of the decision in an Aug. 10 message: “I am going on record . . . to predict that we would more than pay for the installation within the next two years in increased attendance and higher admissions . . .The theaters that will clean up . . . are the theaters who get in on it now while there are comparatively few installations.” Picquet also mentioned that, “Contrary to Mr. Fownes’ report, Pittsburgh’s sound theater is doing a turn-away business and the silent ones are doing almost nothing.”

Perturbed at his general manager’s drumbeating, Tufts suggested Picquet was not fully in tune with public taste. On Aug. 27 he wrote he was “very much impressed at the lack of interest shown (in talkies). Most . . . do not like them and prefer the organ music.” He intimated people in the trade were getting ahead of their own customers.

The correspondence between Tufts and Picquet took on a frostier tone. On Sept. 5, Charlie rubbed it in that the Greensboro sound theater was perpetually “SRO” and that in three months, the resulting profits would pay for the equipment. Three days later, Richard noted the impresario’s ongoing “propaganda on talking movies.” No still meant no.

Picquet took a September vacation to New York, where he enjoyed racing days at Belmont Park but also found time to hobnob with fellow movie people. Not above negotiating in the press, when he returned Charlie informed The Pilot that he had concluded, “after tramping Broadway from end to end . . . the ‘talkies’ are here to stay.” With Tufts still opposed, Picquet tried another tack on Oct. 23. He offered “to ‘hock’ my stock with the bank in order to provide funds for the installation.” So sure was he that Richard and H.C. would find his offer acceptable that Charlie began arranging for purchase of the equipment.

Even that gambit misfired. Fownes still objected. He feared PTC would wind up on the hook morally, if not contractually, if the investment didn’t pan out. On Dec. 17, Picquet informed them he had already personally bought the necessary equipment, but that if “Mr. Fownes is unwilling to allow me to put it in, I would suggest that it be installed in Southern Pines.” Charlie also sounded the alarm that the competing theater in Aberdeen was “rarin’ to install one and will get it, if I do not.”

The frustrated Picquet could not resist taking a potshot at H.C. “Of course, Mr. Fownes does not know it, but the silent pictures from now on are going to be ‘sorry’ affairs . . . No less than 15 silent pictures which were booked for November and December, have been withdrawn to make ‘talkies’ . . . This means that the silent pictures will be junk.”

Finally, Tufts relented, allowing Picquet to install sound synchronization equipment in Southern Pines’ Carolina Theatre. Nelson Hyde’s editorial in The Pilot hailed the coming of the talkies: “This week Charlie Picquet expects to present the first talking picture show ever brought to middle North Carolina.” Hyde cited the “courage of the Carolina Theatre’s management” in bringing about the talkies’ arrival.

On March 7, 1929, Southern Pines’ Carolina Theatre debuted its first talkie, The Iron Mask, starring Douglas Fairbanks in his inaugural speaking role. The Pilot remarked that “Mr. Picquet worked feverishly for two days to assemble his new de Forest Phonofilm projector for the Fairbanks production, and the presentation was voted a great success by those present.”

The Pinehurst Carolina Theatre continued to show silent movies as an alternative to the talking variety exhibited by the sister theater in Southern Pines. In April, a Lupe Velez movie was exhibited in silent form at Pinehurst while the sound adaptation was on view in Southern Pines. The Pilot encouraged moviegoers to check out both versions and reach their own conclusions. The verdict, in the Sandhills and everywhere else, came swiftly: the market for silent pictures had vanished altogether. The Pilot observed in November that, “the Pinehurst house has been playing to handfuls while Southern Pines has been turning people away. No longer will the public go to see silent films while they can witness musical comedies and cry with the tragedians . . . (T)his season was only four weeks along when it became evident to Mr. Picquet and others interested in the Pinehurst theater that times have changed and the old dog is dead.”

Once they observed in the fall of 1929 that silent movies in Pinehurst were playing to a nearly empty theater, Tufts and Fownes swallowed their pride and changed course rapidly. In November, they authorized Picquet to acquire a de Forest projector for Pinehurst and get it installed promptly. As astute businessmen, they may have missed the launch, but they weren’t going to miss the boat. Normal delivery would have taken months. But Picquet managed to expedite matters. The Carolina Theatre Owners Association scheduled its annual meeting in Pinehurst for Dec. 9-10, 1929. Lee de Forest, the inventor of the radio tube and the de Forest projector, was slated to speak at the convention. Charlie reasoned that if talking pictures’ grand opening at PTC could be scheduled to coincide with the gathering, he could prevail upon his fellow theater owners to attend. He pitched to the manufacturer that the conventioneers would make for a target-rich audience for de Forest to showcase their projector in action. His pitch worked; delivery was expedited and the equipment installed at the theater in record time. PTC’s first sound movie was presented on Dec. 9 to a packed house. The Love Parade, a musical comedy starring Maurice Chevalier, was well-received by a crowd seeking respite from the jolt of the stock market collapse. Lee de Forest himself came by to offer remarks to the enthralled audience about the revolutionary synchronization system.

Thereafter, neither theater looked back, enjoying good runs for the next 25 years. As consumer tastes changed mid-century, it became increasingly difficult to economically operate a seasonal movie theater. Pinehurst’s Carolina Theatre showed its last film on April 25, 1954. A local theatrical company performed plays for a time, but in 1962, the Pinehurst theater went permanently dark. Subsequent renovation led by new owners Marty and Susan McKenzie transformed the building into market space by 1981.

Despite advancing health problems and fierce competition from the Sunrise Theatre, Charlie Picquet doggedly kept the Southern Pines Carolina Theatre going. Longtime Southern Pines resident Norris Hodgkins ushered for Charlie at the Carolina Theatre in the late 1930s. Hodgkins remembers that his boss observed formalities not often practiced in other theaters. “Mr. Picquet had us ushers wearing spiffy bellboy uniforms with pillbox hats. If a customer misbehaved, Mr. Picquet tossed him out,” says Norris. “There was no concession stand at The Carolina. No popcorn, no soda. Mr. Picquet believed that food inside the theater detracted from the tone.”

Always nattily attired, Picquet faithfully followed his nightly ritual of personally greeting his theatergoers, then bidding them goodbye after the final credits rolled, a practice he continued until the day he died of a heart attack at age 81 in May 1957. The last movie Charlie showed was a classic: Alfred Hitchcock’s thriller Strangers on a Train. All of Southern Pines’ merchants closed their businesses for an hour to mourn the man who opened the town’s first theater in 1913 — originally named the Princess Theatre — and ran it for 44 years. After Charlie Picquet left its stage, the theater never reopened.

Katharine Boyd paid homage to Picquet in The Pilot, writing that he was “. . . the George M. Cohan type, the trouper through and through: the good friend, the good American.” She noted that Picquet started a competition for musically gifted high school students, the Picquet Cup, and that it “will endure and grow in significance, keeping the name of its donor always before us, up there in the lights where the star’s name goes.”

Today, the Kiwanis Club of the Sandhills continues to hold the Picquet Music Festival each April. Vocal and instrumental students from local high schools compete at the festival for college scholarships. A pioneer and innovator, Charlie’s name remains on the marquee. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.