By Kimberly Daniels Taws

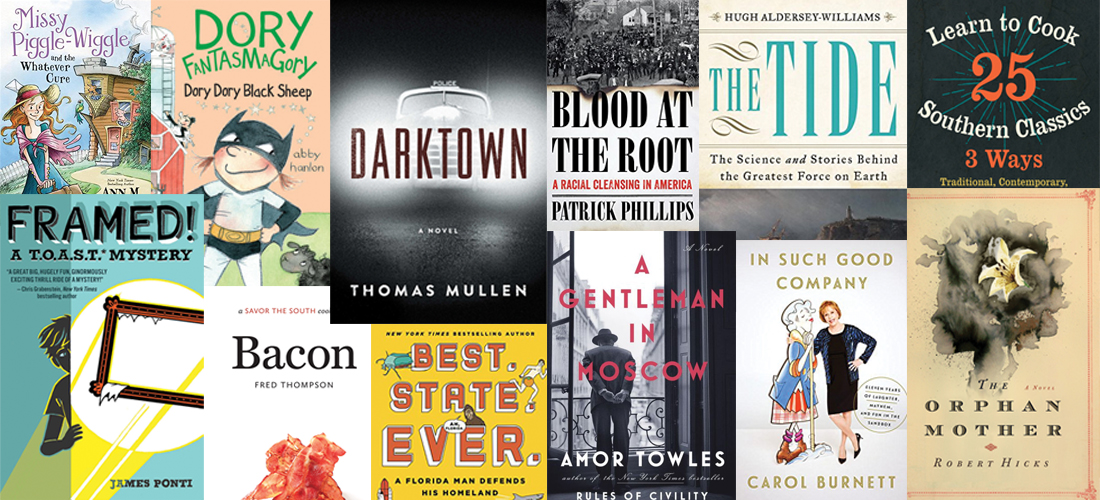

A Gentleman in Moscow, by Amor Towles.

This is an exceptional book, likely to be read over centuries, not just decades. The author of Rules of Civility returns with his sophomore novel about Count Alexander Rostov, sentenced in 1922 by a Bolshevik tribunal to spend the rest of his life in the posh Metropol Hotel, once a grand destination for dignitaries. While the circumstances of Russia change around the hotel, the count maintains his elegance through emotional trials, friendships and adventures that are a pure pleasure to read.

Darktown, by Thomas Mullen.

Follow two of Atlanta’s first black police officers as they investigate the death of a young black woman last seen in the company of a white man. Feel and experience the prejudice and hostility they face from their peers, and ride with the one officer who dared to reach across racial barriers for answers and justice.

The Orphan Mother, by Robert Hicks.

The New York Times best-selling author of The Widow of the South returns with another Southern epic story about Mariah Reddick, the former slave to Carrie McGavock who becomes a midwife in Franklin, Tennessee, following the Civil War. After her politically minded and ambitious grown son is murdered, Mariah seeks the truth and is forced to confront her own past.

A House by the Sea, by Bunny Williams.

Designer Bunny Williams provides a peek into her Caribbean retreat in this wonderful coffee table book. The stunning photographs are punctuated with thoughtful essays by friends on the art of entertaining, gardens and much more.

Bacon, by Fred Thompson.

The author of Fred Thompson’s Southern Sides joins the “Savor the South” cookbook series with a book on bacon that tracks the humble history and our region’s culinary history. The book includes 56 recipes and wonderful information about this popular treat.

Best. State. Ever. A Florida Man Defends His Homeland, by Dave Barry.

The talented Dave Berry applies his trademark humor to a celebration — and high-spirited defense — of the state he calls home, Florida. From Ponce de Leon to modern weirdness, Barry unmasks, as only he can, what makes Florida great.

Blood at the Root: A Racial Cleansing in America, by Patrick Phillips.

Bill Maher writes that Blood at the Root is able to avoid the self-flagellation usually found in similar accounts and, while ugly things in our past history are certainly unpleasant to read about, stirring the dry bones reminds the living how far they have come and how far they have to go.

Enough Said: What’s Gone Wrong with the Language of Politics? by Mark Thompson.

After serving as a CEO of a major TV corporation, director-general of the BBC and now CEO of The New York Times, Thompson continues his career in writing with a deeply thought out examination of the distortion of the public language and new trends in public engagement.

In Such Good Company: Eleven Years of Laughter, Mayhem, and Fun in the Sandbox, by Carol Burnett.

Learn about “The Carol Burnett Show” firsthand as Burnett reveals the show’s truths, from its inception to the many hilarious antics of her co-stars and guests, including Lucille Ball, Bing Crosby, Rita Hayworth and Steve Martin. A great read and a reminder that the great comedic talent still has her touch.

Ingredient: Unveiling the Essential Elements of Food, by Ali Bouzari.

This well-done book is full of pictures and graphs that impart cooking information not widely known. The core of the book is about food in its elemental form. Divided into sections like “Lipids,” “Water” and “Proteins,” this book uses graphs and pictures to explain a seemingly complicated subject in very digestible terms.

Learn to Cook 25 Southern Classics 3 Ways: Traditional, Contemporary, International, by Jennifer Brule.

Brule brings her well-honed recipe testing skills and open, friendly writing to a Southern cookbook that adds modern twists to traditional recipes.

Rancher, Farmer, Fisherman: Conservation Heroes of the American Heartland, by Mariam Horn.

This story looks at five very different professionals tied to the environmental movement. The stories from a Montana rancher, Kansas farmer, Mississippi riverman, Louisiana shrimper and Gulf fisherman all reveal the challenges and powerful myths about American environmental values.

Ten Restaurants That Changed America, by Paul Freedman.

Photographs, images and original menus are not the only parts of this book that bring 10 restaurants and three centuries in America together. The stories of these restaurants provide a social and cultural history revealing ethnicity, class, immigration and assimilation through the shared experiences of food and dining.

The Tide: The Science and Stories Behind the Greatest Force on Earth, by Hugh Aldersey-Williams.

Bringing together folklore, scientific thinking and literature, science writer Aldersey-Williams examines the tides and how we have sought to understand and manage them for centuries.

CHILDREN’S BOOKS

By Angie Tally

Dory Fantasmagory: Dory Dory Black Sheep, by Abby Hanlon.

With best buddies, imaginary friends, a loving mother, a pet sheep from outer space and an imaginary evil nemesis, Dory Dory Black Sheep, the third installment in the Dory Fantasmagory series, really has it all. This is my favorite new chapter book series to recommend to young readers and is perfect for kids who love hearing the Ramona Quimby stories and want something similar to read on their own. Author Abby Hanlon will be at The Country Bookshop at 4 p.m. on Wednesday, Sept 21. Young readers are invited to bring their invisible friends or favorite stuffed farm animals for an afternoon of fun. (Ages 6-10)

Missy Piggle-Wiggle and the Whatever Cure, by Ann M. Martin and Annie Parnell. Missy Piggle-Wiggle arrived in Little Spring Valley on a warm spring morning, moved into the upside-down house owned by her great aunt Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle, was greeted by Wag the dog, Lightfoot the cat, Penelope the talking parrot and Lester the pig, and quickly took up her family responsibility by helping the neighbors, the Free-for-alls, with their (sometimes) lovely children. Written by the delightful Ann M. Martin and Annie Parnell, the great-granddaughter of Betty MacDonald, the author of the original Mrs. Piggle-Wiggle Books, Missy Piggle-Wiggle will delight a new generation of young readers. (Ages 8-12)

Framed, by James Ponti. After most 12-year-olds finish their homework, they play Minecraft or go to soccer practice, but 12-year-old Florian Bates spends his time in a very unusual way: He goes to work for the FBI. Using TOAST, a system of his own devising that stands for Theory Of All Small Things, Florian and his neighbor Margaret help the FBI uncover a foreign government spy ring, assist in the recovery of millions of dollars of stolen paintings, and still makes it home in time for curfew. Readers who love Stuart Gibbs’ Belly Up, E.L. Konigsburg’s Mixed Up Files or Elise Broach’s Masterpiece will love this first in what promises to be a delightful fun mystery series. (Ages 9-12) PS