SAM

Sam

A kid’s Christmas with an all-time great

By Bill Case

I was 17 and in my senior year at Hudson High School, in the Ohio town of the same name, when I was informed by my parents, Bea and Weldon Case, that we would be spending the 1965 holiday season in Boca Raton, Florida, where they had recently bought an oceanside condominium. I harbored mixed feelings about leaving my hometown during Christmas break — I would miss hanging out with my friends and, for me, the snow blanketing northeastern Ohio reflected the spirit of the holidays better than palm trees.

But there was an undeniable plus to a Christmas vacation in Florida. My folks were members at the Boca Raton Hotel & Club and they assured me I could play golf there. I loved golf and had developed a decent game, sporadically breaking 80; good enough to start on Hudson’s golf team the previous spring. With the ’66 season fast approaching, a few rounds in the sun would give my game a boost.

I started playing golf when I was 8, mostly with my mother, who demonstrated considerable patience with my beginner’s futility. Improvement was agonizingly slow. When I was 10, I finally broke 60 for nine holes, carding a 59. Prior to this personal breakthrough, the legendary Sam Snead had posted a 59 of his own at the age of 46 in the Sam Snead Festival at The Greenbrier where The Slammer served as head professional. As the first sub-60 round shot in a professional event, Snead’s achievement had caused a big buzz in golf circles. Though my score was for only nine holes, our respective 59s created a sort of bond between Sam and me, if only in my imagination.

As a result, Snead became one of my favorites. Mesmerized by the rhythm of his swing, I sought him out in Ohio tournaments like Akron’s American Golf Classic and the Cleveland Open. The year before our Boca vacation, I followed Sam’s group at a practice round during the Thunderbird Classic in Rye, New York. Playing with the seven-time major champion were three young pros I’d never heard of. I knew from reading Snead’s autobiography, The Education of a Golfer, that he was more than happy to take on all comers provided there was money on the line and the wagers to his liking. The chapter titled “Hawks, Vultures, and Pigeons: Gambling Golf” revealed his betting tips. The grousing I overheard at the Thunderbird from his playing partners (i.e., pigeons) confirmed that Sam, per usual, was cleaning up.

On the eve of my first round of golf on our Florida vacation Dad said to me, “There’s a good chance you’ll see Sam Snead tomorrow. You know, he’s Boca Raton’s pro during the winter.” The prospect of encountering Sam, perhaps even meeting him, jumpstarted an adrenaline rush.

I would be going to the course as a single, at least on that day. Mom was finalizing Christmas preparations and Dad was needed on a business call, immersed as he was in expanding the business of Mid-Continent Telephone Corporation, a holding company he and his three brothers founded in 1960. His duties as Mid-Continent’s president left little time for golf, but like many corporate executives, Dad did enjoy playing in pro-ams. He drew several of the game’s greatest as his partners, including Jack Nicklaus, Gary Player, Julius Boros and Tom Watson, twice. On these occasions, Dad, sporting a 14 handicap and a unique golf swing, generally worked his way around the course without embarrassing himself. He attacked the ball with a ferocious fire-and-fall-backward lunge that left observers scratching their heads. Prior to his second game with Watson, Tom greeted him this way: “I’m sorry, sir. I’ve forgotten your name. But I’ll never forget that swing!”

Dad did find time to drive me over to the club in the morning. He told me to take a caddie and handed me $10 to pay the man. I considered this rather extravagant since I generally received just $6 for a double-bag loop at Hudson’s Lake Forest Country Club, but it was Dad’s money, so fine. When I arrived on the putting green at the Boca Hotel’s course, I met my caddie, Jack, a rawboned, wizened smoker probably four times my age. “It’ll be slow out there since you’re a single,” he cautioned me. “And the group in front of us is a fivesome.” A fivesome! That seemed peculiar for a posh resort. “Won’t they let us play through?” I asked.

Following a prolonged drag on the vanishing stub of a Marlboro, Jack shook his head. “Not likely. It’s Mr. Snead’s group.”

It was then that I peered over my shoulder and saw Sam Snead in his signature coconut straw hat, rolling a few putts. “Well,” I thought, “I’m in no hurry, and I’ll get to see Sam hit plenty of shots.”

And that’s what happened for the first two holes. But while waiting at the third tee for Snead’s group to clear the fairway, I saw him, roughly 250 yards away, misfire on his second shot. He angrily launched his club high into the air toward the green. It seemed eons before the whirly-birding iron fell back to Earth — a remarkable, but troubling, sight. The great man seemed in a foul mood. Perhaps Sam was on the losing end that day.

When Jack and I mounted the tee of the sixth hole, a 185-yard par-3, I saw Sam off to the side of the green with his hands on his hips, shaking his head impatiently. His body language left no doubt he was exasperated. I gathered his displeasure stemmed from the inability of a player in his group to escape a greenside bunker.

As I took all this in, the agitated Snead turned in my direction, raised his arm, and waved at me to hit up. An electric shock coursed through my body at the prospect of playing through the immortal Slammer and his fivesome. My hands shook so much it was a struggle to tee up my ball.

Somehow, I steadied enough to strike the shot solidly with my 4-wood. The exhilaration I felt watching the ball fly onto the green and spin to a stop 20 feet from the pin was overwhelming. This tee ball, struck 60 years ago, remains the single most memorable shot of my golfing life. My spikes barely touched the ground as I galloped off the tee toward the green. And even the wheezing Jack found a renewed spring in his step.

At the green, I thanked Snead and his playing partners profusely for their courtesy. But Sam, still miffed, did not react. No “nice shot,” no “take your time,” nothing, except his glowering demeanor. Was it something I’d done? Had I appeared impatient in waiting to play? Anxious to exit Snead’s presence and without lining up, I lagged my putt to a foot of the hole and tapped in. Jack and I double-timed it to the seventh tee as I hyperventilated.

When Dad picked me up after the round, I told him about the sixth hole in vivid detail. “Isn’t it great you got to see one of the greatest golfers of all time, Samuel Jackson Snead?” he said and smiled. “And isn’t it great you rose to the occasion by hitting a good shot? The only thing better would be playing head-to-head with Sam.” I appreciated Dad’s praise, but this “head-to-head” stuff seemed odd.

Christmas morning arrived two days later. I had asked my folks for a Ben Hogan “Sure-Out” model sand wedge (golfers of my vintage will recall its huge flange). The “Sure-Out” had been the difference maker for Julius Boros in his victory at the 1963 U.S. Open. To my delight, the coveted wedge, adorned with a bow around its mammoth flange, was my final present.

Or so I thought. That was when Mom, with a mischievous glint in her eye, said, “Oh, Weldon, don’t we have another small gift for Bill?”

“Almost forgot, but it’s right here,” Dad reached into the pocket of his robe, pulled out an envelope and handed it over. I assumed that inside was a check, maybe for as much as $25. But instead I found a note in Dad’s handwriting. It read, “You have a tee-time tomorrow at 9:40 a.m. at the Boca Raton Hotel & Club. Your playing partner is Samuel Jackson Snead.”

I was thrilled, stunned, grateful, humbled and over-the-moon. A round with Sam Snead was the most incredible present a young aspiring golfer could imagine. During his epic career, Snead would win 82 PGA tour events, tied decades later by Tiger Woods for the most all-time. He had been triumphant in every important tournament except the U.S. Open where, to his frustration, bizarre occurrences had torpedoed several near victories. His name belongs among the greatest of all time with Jack Nicklaus, Woods, Bobby Jones and his contemporaries Ben Hogan and Byron Nelson, both of whom, like Sam, were born in 1912.

My initial elation was followed by a second wave of worry, intimidation and even dread. Aside from the 4-wood shot, my recent exposure to the Slammer had not been particularly agreeable. If I played like a dog, like the poor soul who couldn’t escape the bunker two days before, would Sam treat me with disdain? He’d certainly been frosty enough on the sixth green.

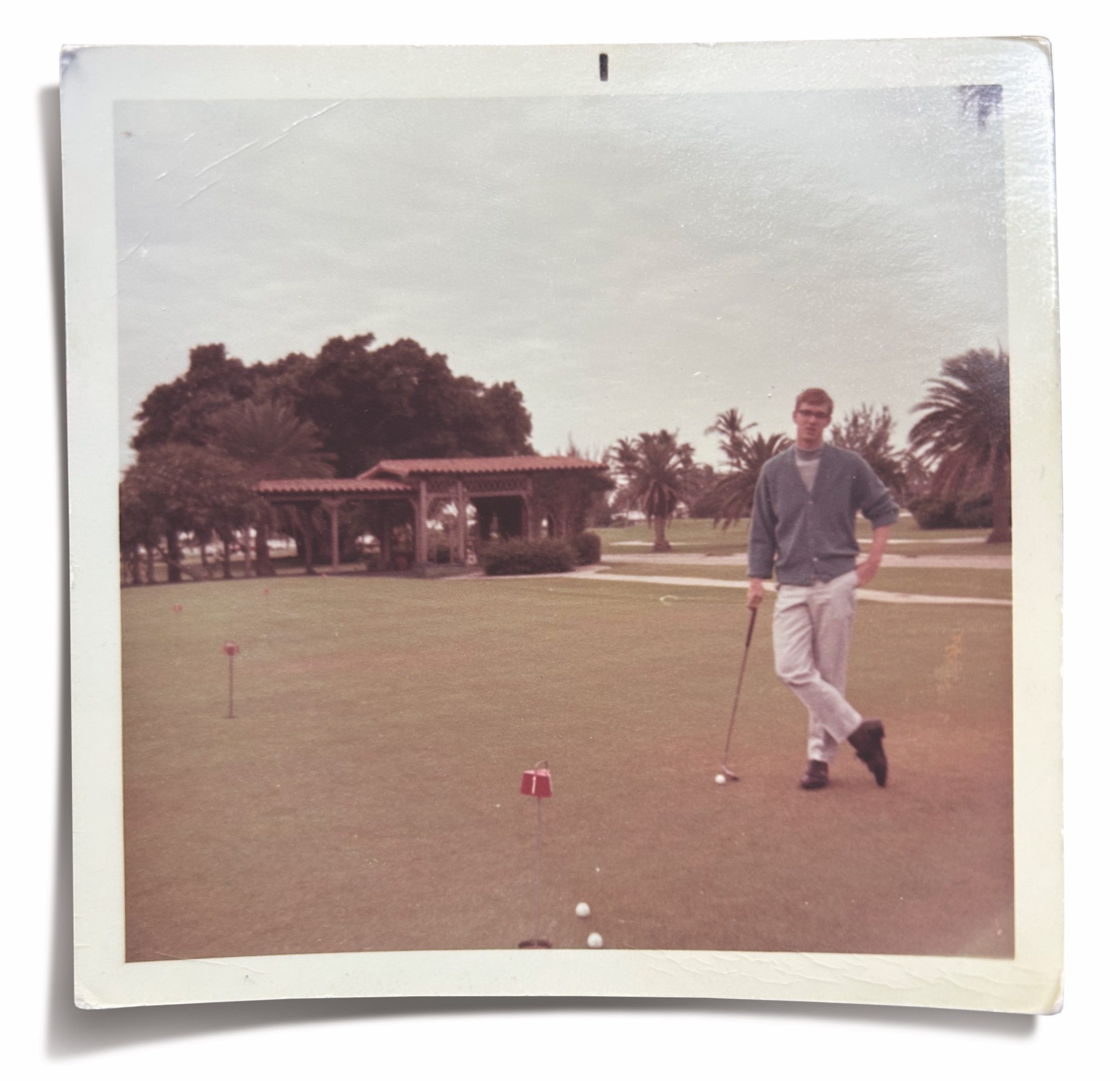

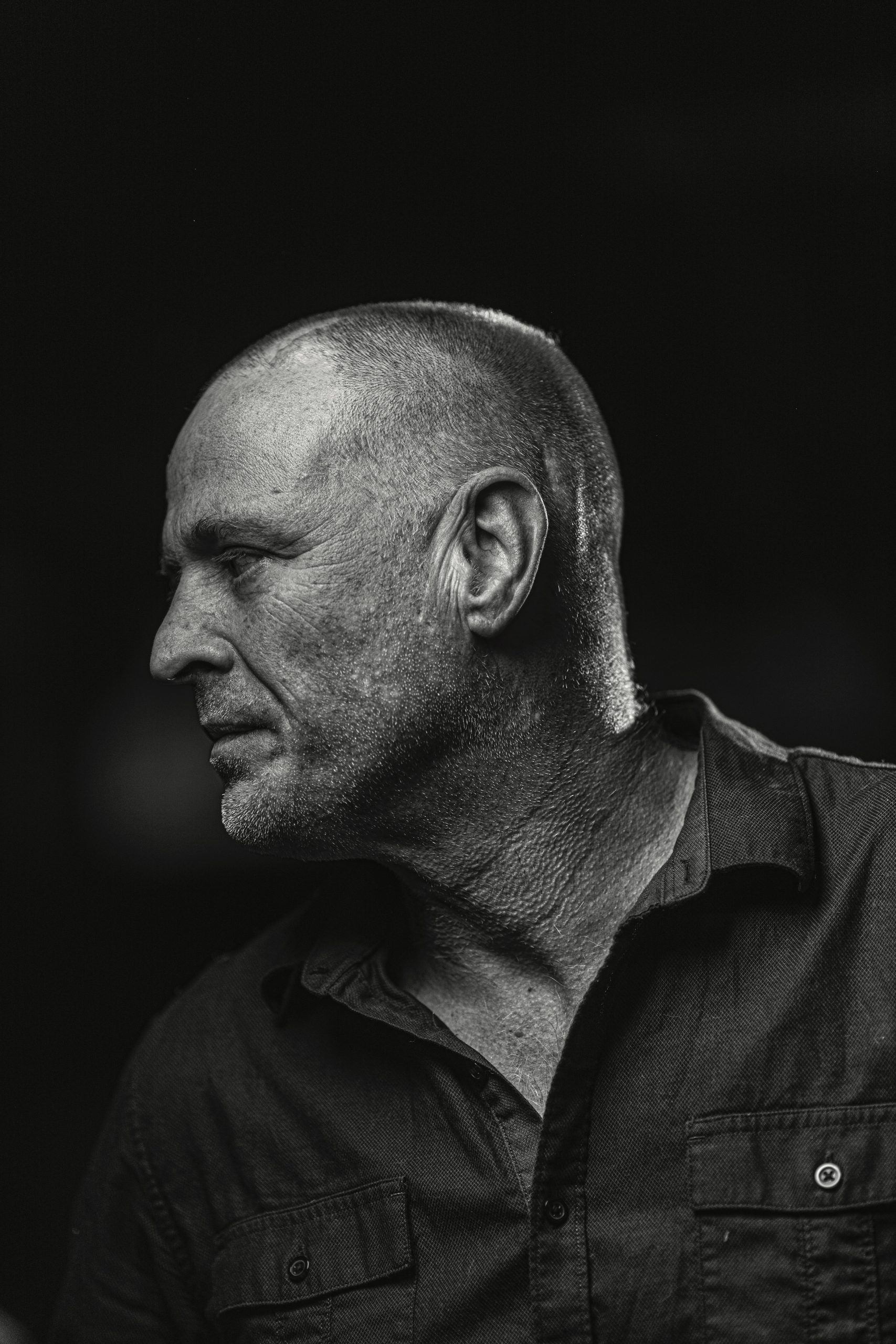

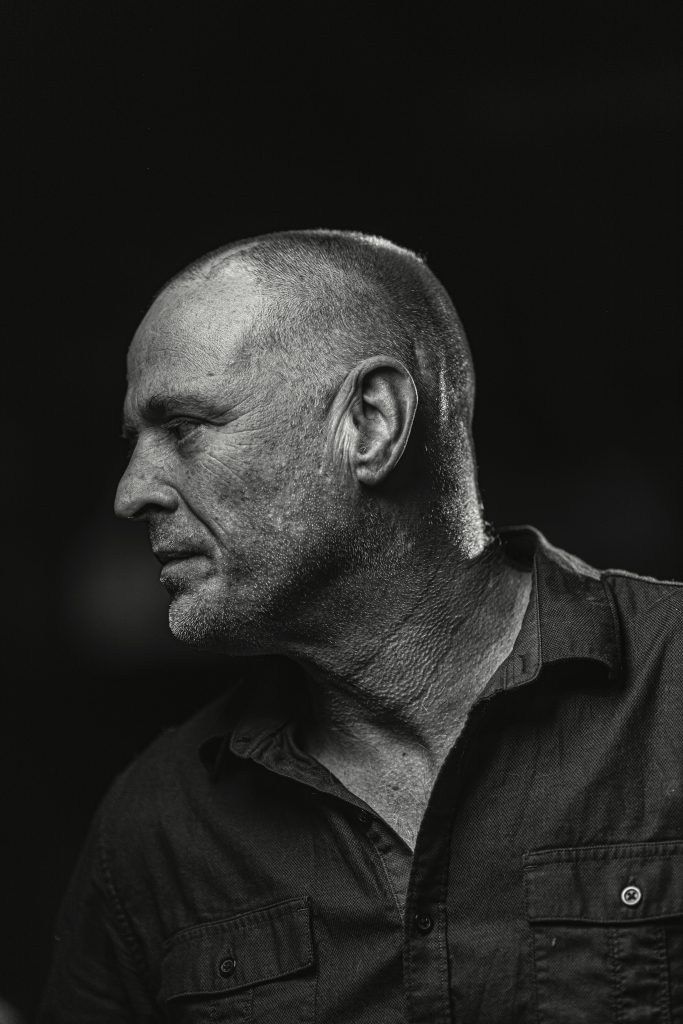

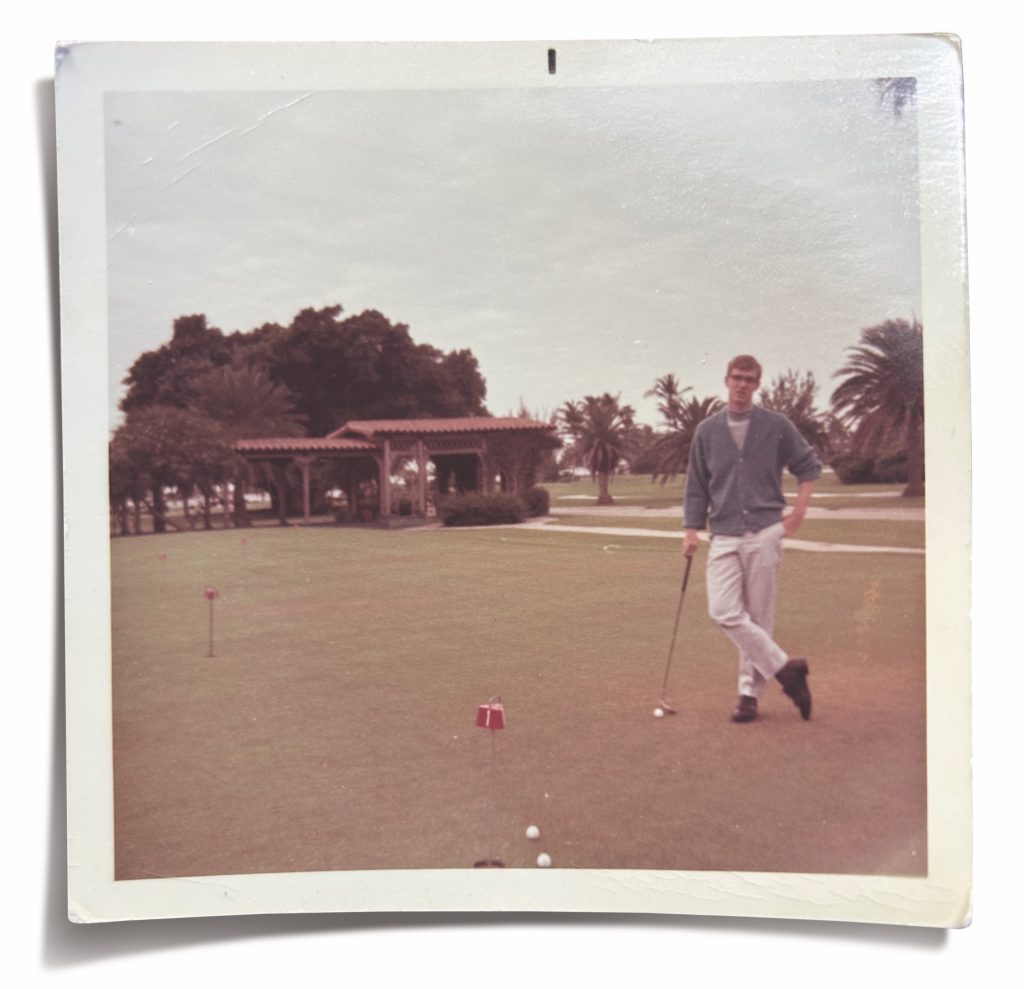

After a fitful night’s sleep. Dad drove me over to the club the next morning. Instead of dropping me off, he parked the car and escorted me to the putting green, where he snapped my picture, a lanky 160-pounder on a 6-foot-1 inch frame. At the appointed time, Dad and I entered the pro shop, where we met Sam. He couldn’t have been friendlier.

“Nice to meet you,” he greeted us in his smooth Virginia mountain drawl. “Bill, I hear you play on your high school team. That’s great. It’ll be just the two of us; we’ll have a good game. And just call me Sam.”

Out to his golf cart we went. Before we teed off, Dad took another photograph, this time of Sam and me. I confess, I’ve lost track of it but I well recall a broadly smiling Snead, nattily attired in red slacks, navy blue alpaca sweater and the ever-present straw hat sitting beside me, who was clearly starstruck.

Boca’s course was jammed, and I envisioned a protracted five-hour round. But when Sam and his familiar straw hat came into the view of players in the group ahead, they invariably waved him through. It was as if the Red Sea parted for us as we sped through foursome after foursome. Since Snead graciously allowed me to hit first off each tee, the golfers in our wake may have concluded I was winning our friendly match. Far from it.

Playing from the regular white tees, Sam nonchalantly made par or birdie on every hole. I was doing OK, mostly avoiding serious trouble. Then I made an unforced error by cutting things too close in laying up short of a stream crossing the fairway. After my ball toppled over the edge and into the water, Sam pithily observed, “If you’re going to lay up, lay up.” Over the years, I have often repeated his advice to players making the same mistake — and I let them know who gave it to me.

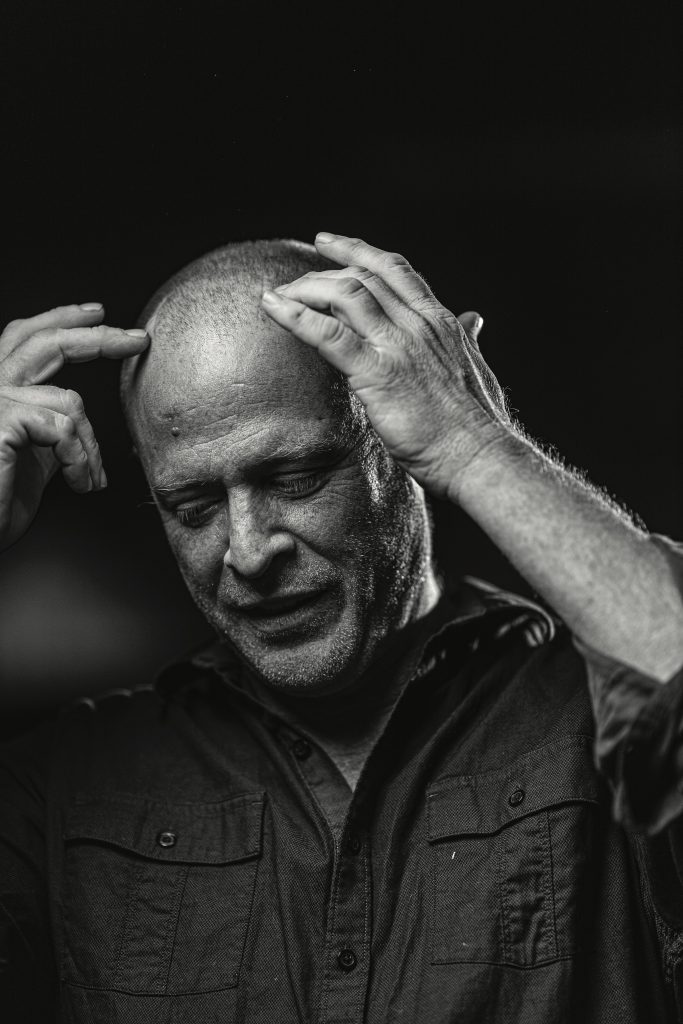

Sam was pleasant, but he tended to let me take the lead in our communications. And I felt some pressure to fill the airspace. I had one advantage making conversation — I had read The Education of a Golfer. I asked Sam questions about how he went about fashioning a club from a swamp maple tree limb during his youth. I asked about a boxing match he fought during his teens. And, of course, I fished for details about that incredible 59. The round, it turned out, could have been one shot better since Sam had missed a 2-foot putt.

Then I delved into the betting chapter of the book. Sam quickly warmed to this subject, regaling me with colorful anecdotes about how sharks he encountered tried to fix bets to their advantage. One sought additional strokes by claiming he had recently arrived in Florida from the North and hadn’t touched a golf club all winter. Actually, the hustler had been playing in the Sunshine State for weeks, even trying to conceal his tan from Snead by whitening his hands and face with corn plaster. Sam countered by carefully feeling the man’s calluses when shaking his hand. “When those calluses are thick, that tells you the man’s been playing plenty,” he said.

At one point on the front nine, Sam struck a shot he considered not up to his standard. He muttered, “I just can’t play my best unless I got a bet going.” I responded rather cheekily, “Well, I am sorry, Sam, that I won’t get to see you at your best.” Silence from the Slammer. To my surprise, I was hitting my drives within 20-25 yards of Sam’s. Since he was then 53, I figured he must be losing yardage off the tee. Wondering how much, I began posing a question with, “Now, when you were at your peak . . . ”

As the words left my mouth, I knew this was a misstep. Even assuming his peak was behind him, Snead wasn’t about to acknowledge it. Besides, Sam was still playing great golf in 1965. He finished 24th on the PGA tour money list (there was no Senior or Champions tour available in ’65) despite playing in only 15 events. Snead had won his seventh Greensboro Open earlier in the spring, making him the oldest (52) to have won a PGA Tour event. The record still stands 60 years later.

In a feeble effort to erase my faux pas, I uttered something inane along the lines of, “Not that you aren’t still at your peak.” I forget what was said next but do recall a distinct, if brief, lull in our conversation. If Sam was annoyed by my babbling, he didn’t show it, and our amiable dialogue resumed. It is telling that on the hole following my misbegotten inquiry, Sam let out the shaft and outdrove me by 75 yards.

Dad was waiting for us as we finished on the 18th, done in 2 hours and 45 minutes. After holing out and shaking hands (Snead, quite bald, never removed his hat in these situations), Dad asked Sam how things went.

“Well, your son did just fine,” he offered. “Shot 82 and kept the ball in play — just one double bogey and that was from a mental mistake (the bonehead lay-up). I believe he learned a lesson from that. He should keep on playing.” I absorbed another lesson from the round: Think before you speak.

Sam shot 66 and didn’t seem to be doing anything special. He holed one long putt and birdied the par 5s, but otherwise his round appeared relatively routine. Had I the temerity to bet him, I would have become one of Sam’s countless “pigeons.”

I don’t know for sure the amount Snead charged for the round. I think it was around $150. An old pro friend of mine believes that figure is too low, but an aged article I unearthed in the Sports Illustrated archives reported that in 1959, Snead charged $50 per round and $25 for each additional player. I can only imagine what a superstar like Sam would charge today.

Regardless of the cost, playing with Snead was priceless. There are still times when I have failed to do as Sam counseled — lay-up shots still occasionally roll into the water. But I’ve faithfully followed his advice to keep playing. After all, golf is the game of a lifetime. And my life was enhanced by that unexpected 1965 Christmas present.