Nothing says Southern cooking more than a plate of fried green tomatoes

By Jane Lear

The tomato is a tropical berry — it originated in South America — and so it requires plenty of long, hot sunny days to reach its best: the deep, rich-tasting, almost meaty sweetness many of us live for each summer. When September rolls around, though, it’s a different story. It’s not that I’ve gotten bored with all that lush ripeness, but I develop a very definite craving for fried green tomatoes.

If you grow your own backyard beefsteaks, unripe tomatoes are available pretty much all summer long, but this is the time of year they start getting really good. In the early autumn, the days are undeniably getting shorter, and thus there are fewer hours of sun. That and cooler temperatures result in green tomatoes with a greater ratio of acid to sugars.

And my cast-iron skillet, which tends to live on top of the stove anyway, gets a workout. Fried green tomatoes, after all, are terrific any time of day. In the morning, they are wonderful sprinkled with a little brown sugar while still hot in the skillet, right before you gently lift them onto warmed breakfast plates. If you’re a brunch person, serve them that way, and you’ll bring down the house. At lunchtime, embellishing BLTs with fried green tomatoes may seem like a time-consuming complication, but those sandwiches will be transcendent, and you and yours are worth it.

When it comes to the evening meal, fried green tomatoes are typically considered a side dish, and there is nothing wrong with that. But in my experience, they always steal the show, so I tend to build supper around them. I rely on leftover cold roasted chicken or ham to fill in the cracks, for instance. Or I make them the center of a vegetable-based supper in which no one will miss the meat. They play well with corn on the cob or succotash, snap beans or butter beans, ratatouille, grilled zucchini and summer squash with pesto, or grits, rice, or potatoes. Pickled black-eyed peas (aka Texas caviar) are nice in the mix, as are sliced ripe red tomatoes, which, when served alongside crunchy golden fried green tomatoes, add a great contrast in texture and flavor.

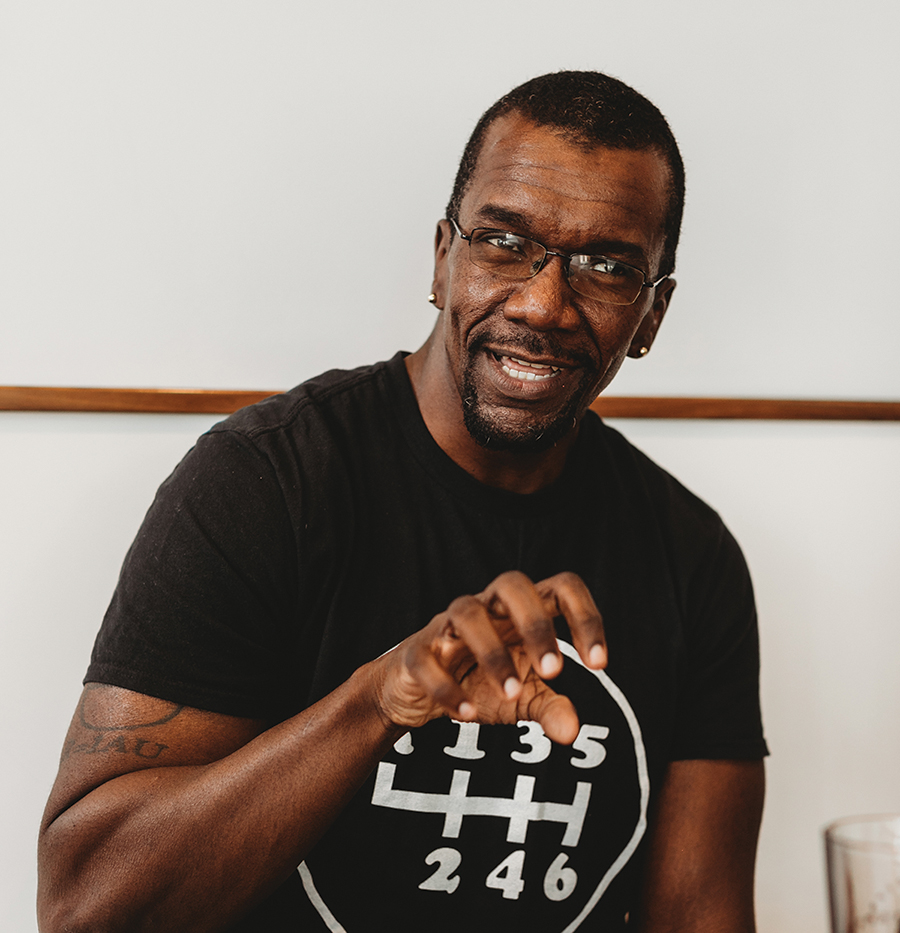

If you are fortunate enough to have a jar of watermelon rind pickles in the pantry, my Aunt Roxy would suggest that you hop up and get it. I ate many a meal in her cottage on Harbor Island, and early on I learned watermelon and tomatoes have a curious yet genuine affinity for one another. I imagine Aunt Roxy would greet today’s popular fresh tomato and watermelon salads with a satisfied nod of recognition.

We always had a difference of opinion, however, over cream gravy, a popular accompaniment for fried green tomatoes. It’s not that I am morally opposed to lily gilding, but I have never seen the point in putting something wet on something you have worked to make crisp and golden. A butter sauce on pan-fried soft-shelled crabs, chili or melted cheese on french fries, a big scoop of vanilla on a flaky double-crusted fruit pie: I don’t care what it is, the result is soggy food, and I don’t like it.

When it comes to the actual coating for fried green tomatoes, the most traditional choice is dried bread crumbs. I sometimes use the crisp, flaky Japanese bread crumbs called panko, but like Fannie Flagg, I am happiest with cornmeal. It can be white or yellow, fine-ground or coarse. It doesn’t matter as long as it is sweet-smelling — a sign of freshness. And if you happen to have some okra handy, you may as well fry that up at the same time. Trim the pods, cut them into bite-size nuggets, and coat them like the tomato slices. Although rule one when frying anything is not to crowd the pan (otherwise, the food will steam, not fry), there is always room to work a few pieces of okra into each batch of tomatoes. And whoever you are feeding will think you hung the moon and stars.

Fried Green Tomatoes (Serves 4)

When cutting tomatoes for frying, aim for slices between 1/4 and 1/2 inch thick. If too thin, you won’t get the custardy interior you want. And if the slices are too thick, then the coating will burn before the interior is softened.

About 1 cup of cornmeal

Coarse salt and freshly ground pepper

1 large egg, lightly beaten with a fork

4 extremely firm (but not rock-hard) large green tomatoes

Vegetable oil or bacon drippings (you can also use a combination of the two)

Preheat the oven to low. Season the cornmeal with salt and pepper and spread in a shallow bowl. Have ready the beaten egg in another shallow bowl. Cut the tomatoes into 1/2-inch slices (see above note).

Pour enough oil or drippings into a large heavy skillet to measure about 1/8 inch and heat over moderate heat until shimmering. Meanwhile, working in batches, dip one tomato slice at a time into the egg, turning to coat, then dredge it well in the cornmeal. As you coat each slice, put it on a sheet of waxed paper and let it rest for a minute or two. (This is something I remember watching Aunt Roxy do. It must give the cornmeal a chance to absorb some moisture and decide to adhere.) By the time you coat enough slices to fit in the skillet, the fat in the pan should be good and hot.

Carefully, so as not to dislodge the coating, slip a batch of tomato slices into the hot fat (do not crowd pan) and fry, turning as necessary, until golden on both sides. Drain the slices on paper towels and transfer them to a baking sheet; tuck them in the oven to stay warm and crisp.

Coat and fry the remaining tomato slices in batches, wiping out the skillet with a paper towel and adding more oil or drippings as needed. Be patient and give the fat time to heat up in between batches. You may find yourself eating the first slice or two while alone in the kitchen, but be sweet and share the rest. PS

Jane Lear was the senior articles editor at Gourmet and features director at Martha Stewart Living.