THE ART OF N.C. WYETH

The Art of N.C. Wyeth

How did his illustrations for Drums get here?

By Bill Case

It was 1927 and, for Southern Pines author James Boyd, life was coming at him fast — albeit in a good way. His first novel, Drums, published two years earlier, had flown off bookstore shelves. To meet the unanticipated demand, publisher Charles Scribner’s Sons had reprinted the novel three times in the first month following its release. Forty thousand copies of the surprise bestseller were sold in five months.

Boyd’s tale, set mostly in North Carolina, was also earning critical acclaim. A New York Post reviewer declared Drums “the best novel written about the American Revolution.” Fellow author (and Boyd confidante) Struthers Burt heaped more extravagant praise, calling his friend’s work, “by far the best . . . American historical novel ever written.”

Buoyed by his surprise hit, Boyd authored a second historical novel for Scribner’s — this one with a Civil War backdrop. The book, titled Marching On, released in the first quarter of 1927, was going gangbusters too. Early sales were bettering those of Drums. On the heels of this latest tour de force, Scribner’s inked a deal for a third novel.

While Boyd’s association with his publisher was financially profitable, it was proving more time-consuming than he preferred, expressing frustration when production demands precluded his engagement in his favored rural pastimes, like foxhunting. The author grumbled to an interviewer, “My brother looks after my money for me; my wife looks after my kids and the house; now if I could get you (the interviewer) to do my writing for me, I could look after my dogs myself and fox hunt during the winter. Seems to me that would be an ideal arrangement for everybody concerned.”

In the fall of 1927, Boyd’s renowned editor, Max Perkins, pitched a new project designed to create a fresh wave of sales — and the author would barely need to lift a finger! Scribner’s wanted to produce a new, lushly illustrated edition of Drums. Boyd would need to make some minor text changes, but the bulk of the creative work would involve the artistic depiction of passages from the novel.

This was not a new concept for Scribner’s. The publisher first featured color illustrations in children’s books in 1904. Well-received, Scribner’s began color illustrating full-length novels, aiming primarily at the juvenile trade. An early one was Treasure Island, published in 1911. A landmark hit, Robert Louis Stevenson’s swashbuckling yarn became the first in a series labeled “Scribner’s Illustrated Classics.”

Subsequent books in the series like Kidnapped, Rip Van Winkle and The Last of the Mohicans told stories of high adventure. The authors of those classics, Stevenson, Washington Irving and James Fenimore Cooper, respectively, rank among the greatest American writers. The fact that Boyd was joining these legends underscored his arrival on the literary scene.

The choice of Drums for the series represented a departure for Scribner’s. While the book contains battle episodes and other dramatic moments, its subject matter was aimed at mature readers. In Drums, intractable political conflicts and social class barriers bedevil the young protagonist, Johnny Fraser. Editor Max Perkins minimized any perceived switch in Scribner’s targeted audience, writing, “Most of the best books in the world are read both by children and adults. This is a characteristic of a great book, that it is both juvenile and adult, and that is what assures it a long life.”

The primary conflict in Drums occurs in the lead-up to the war, when Johnny Fraser is coming of age in the backwoods of North Carolina, and Americans are bitterly divided on the issue of independence. Johnny’s father, Squire Fraser, sees both sides; while acknowledging that taxation without representation is anti-democratic, he is convinced no good will come from revolution. He remains a Loyalist, and Johnny follows his father’s lead.

Squire Fraser seeks to keep his son out of the growing tumult by sending him to Edenton to receive a gentleman’s education, but after war breaks out in Massachusetts, the revolt impacts Edenton, too. The British collector of the port there, Captain Tennant, is forced by a jeering mob to leave the colony. Johnny, a wavering Loyalist, receives his own share of harassment and also departs Edenton. Squire Fraser, still protecting his son, arranges for Johnny’s passage to England, where the young man obtains a clerical position at an import firm in London.

It’s then that Johnny crosses paths with American naval hero John Paul Jones, the “Father of the American Navy.” Jones persuades Johnny to join his ship’s crew. Whether his decision is premised on a newfound fervor for independence or the urging of the charismatic Jones is for the reader to discern.

Johnny is wounded in battle aboard Jones’ ship, the Bonhomme Richard. He returns to North Carolina and rejoins his parents in the backwoods of Little River. Fully invested now in the cause of independence, Johnny joins the militia and is wounded again. The book concludes with the battered Johnny Fraser sitting on his front porch, watching Nathanael Greene’s victorious army march by. As the soldiers are nearly out of sight, he staggers down to the fence and raises his stiff arm in salute to the last man of Greene’s rear guard, far off in the distance.

Scribner’s assigned the artwork for the new edition of Drums to the man unquestionably regarded as the finest illustrator in America, Newell Convers Wyeth, age 45. N.C. Wyeth painted the bulk of the artwork contained in the Scribner’s classics series, beginning with Treasure Island. During his unparalleled career Wyeth also illustrated hundreds of scenes for magazine stories, especially those published by Scribner’s Magazine and the Saturday Evening Post.

Wyeth was raised in Needham, Massachusetts, where his father made a decent living dealing in hay, grain and straw. His mother, an immigrant from Switzerland, was chronically homesick for her place of birth, and her depressed state was an ongoing drain on the family. Nonetheless, N.C. maintained a close relationship with his mother, and after he left Needham, the two corresponded with one another almost daily.

Wyeth displayed immense artistic ability during his teenage years, attending the Howard Pyle School of Art in Wilmington, Delaware. Pyle was then the country’s leading illustrator and quickly recognized Wyeth’s talent, advising his prodigy to submit illustrations to magazines. One of his first compositions was for The Saturday Evening Post — a cowboy astride a bucking bronco that appeared on the Post’s cover the week of Feb. 21, 1903. It was a promising start, and with magazines catering to public thirst for Western-themed stories, Wyeth received multiple commissions.

Pyle believed Wyeth’s cowboy illustrations would gain authenticity if he experienced Western life for himself, so in October 1904, N.C. journeyed west and found employment at a ranch. On Oct. 6, he wrote his mother: “I did my first work of the cowpuncher . . . Elroy and I went out and rounded up about 300 head of cattle, including calves. We started at 7:30 a.m. and were in the saddle continually until 5:15 that afternoon.”

Wyeth remained out west until December. The sojourn led to an explosion in commissions, and Wyeth’s subsequent Western illustrations demonstrated an increased grit and realism gained from his personal experience. With his career off and running, he received offers from magazines at the rate of two or three a week, and demand for his illustrations never slowed. Yet, he often disparaged this genre of painting as unserious, purely commercial and barely art. Though painting illustrations brought him fame and prosperity, Wyeth groused that it prevented him from being “able to paint a picture, and that is as far from the realms of illustration as black is from white.”

Churning out illustrations, however, earned enough to support a burgeoning family. He married Carol Bockius in 1906, and they had five children. Several of his offspring would become talented artists in their own right, most notably, celebrated mid-century painter Andrew Wyeth. In 1908, N.C. moved the family to bucolic Chadds Ford, Pennsylvania, in the Brandywine Valley, 10 miles from Wilmington, Delaware. He had become smitten with the community’s horse-drawn surroundings during Pyle’s summer school sessions.

Wyeth relished life in Chadds Ford. Its warm meadows and rolling hills provided an idyllic environment for his work. Author David Michaelis described the painter’s peripatetic labors in his biography, N.C. Wyeth: “He had no time to waste. He divided his days, pushing himself to do more than one person could. In the mornings he made studies in the open fields around Chadds Ford. After lunch he cranked out pictures for Scribner’s and The Saturday Evening Post, then returned to the open air in the late afternoon. As the evenings lengthened in May, he remained in the fields and on the riverbanks, sketching, often through supper.”

The hard work paid off. Wyeth’s Scribner’s Illustrated Classics paintings received increasing acclaim. His depictions stood out because they appealed to all the senses. Michaelis wrote, “Wyeth’s illustrations make the viewer not only see and feel but also hear. We hear the clatter of dishes and goblets breaking during a fight, coins falling on heaps, sand squeaking under the feet of the stretcher bearers.”

Illustrator John Lechner added, “Unlike previous illustrators, who designed their compositions neatly on the page, Wyeth’s paintings leapt right out of the book, with a vibrancy and power that made you feel the passion and pain of their subjects.”

An assignment from Scribner’s to illustrate a classic novel required production of 17 individual paintings. Fourteen of them, each depicting a scene from the book, would be sprinkled throughout the text. The cover, title page and end page would also feature illustrations. Scribner’s art director, Joseph Chapin, allowed Wyeth carte blanche freedom in choosing scenes.

Lechner observed the subtlety within N.C.’s selections: “Wyeth was very sensitive to the author’s words, and his philosophy was to avoid depicting scenes that the author describes in detail (what was the point?) and instead illuminate smaller moments that are only briefly mentioned, in order to enhance the story. The resulting illustrations are neither trivial nor superfluous but help develop the characters and advance the story.”

Wyeth used canvases for the classics series that were 47 inches tall and 38 inches wide. For final publication, Scribner’s engravers would reduce the size to 6 1/2 inches by 5 1/4 inches. Wyeth was billing Scribner’s approximately $5,000 for a set of paintings around the time the publisher retained him to illustrate Drums.

Wyeth always read the novel he was illustrating. We know he liked Drums because of a letter he wrote to his father, who apparently did not share his enthusiasm. Recognizing his father was accustomed to stories involving the confrontation of a perfect hero with a perfect villain, N.C. asserted that real life was not like that, claiming modern literature, and Drums in particular, provided more realistic, and thus more interesting, portrayals of human nature. The imperfect Johnny Fraser, according to Wyeth, was “like most of us,” a “fundamentally worthy sensitive person,” yet “vacillating and a victim of influence and circumstances.”

His western trip taught Wyeth that the essence of a scene is best captured by exploring the area where the action occurs, so plans were made for him to visit Edenton. Who initiated the trip is unclear, but Boyd — who had previously visited Wyeth in Chadds Ford — did send Wyeth a telegram inviting him to visit Weymouth on his way to Edenton.

Wyeth responded on Dec. 3, 1927. “I have carefully completed the next to last study of Drums and am now prepared to absorb the material I need from you, Little River Country, and Edenton.” Wyeth planned to arrive at Weymouth on Wednesday, presumably Dec. 7.

The next recorded contact between the author and artist took place later in December when Wyeth wrote Boyd from Edenton extending his “warmest thanks to you and Mrs. Boyd for your kindnesses.” He expressed further gratitude to Boyd “for the use of your motor,” and the “careful but not dull driving of Calvin.” Wyeth’s word pictures were nearly as lush as his illustrations. “For the last two hours, lying by the open window, I have listened to the night sounds of this little town and have contrasted those Johnny Fraser heard so often, and by doing so have enjoyed revealments which, for moments of time, become very poignant and moving,” he wrote. “Dimly bulking against the glow of the moon on the water I can see the angular shapes of three warehouses. There they stand as Johnny Fraser saw them! This afternoon was spent wandering in and about these relics of 1770. My heart went out to them, because you, Boyd, have made them live for me.”

Wowed by N.C.’s eloquence, Boyd responds, “It is an injustice of nature that a man who can paint like you should also be able to write like that . . . I might be obliged to ask myself why I am in the business at all.” Boyd is also struck by the fact that Wyeth’s sentiments present a perfect echo of his own. “Two people are seldom so as one on anything in life,” Boyd writes. “And when that thing happens as with us to be a common enterprise, the coincidence is so far-fetched as to excite a wonder in my mystical Scots nature, only exceeded by my hard-headed Scotch-Irish nature that there must be a catch somewhere.”

There is no hint in their correspondence that James Boyd accompanied Wyeth on his coastal wanderings, but a humorous anecdote in the Jan. 10, 1931 Pinehurst Outlook suggests otherwise, claiming that Wyeth was seeking models for two boys in the story, and that he and Boyd toured the Cape Fear area together in search of suitable subjects. “Stopping at a country school near Wilmington, they looked through the windows and saw in a corner two boys who served Mr. Wyeth’s purpose very well. He and the author, to get a closer view, stooped down and looked through the keyhole. ‘Just the type,’ said the artist, and the author agreed. The schoolteacher, unfortunately, overheard the conversation and opened the door to investigate, and both Mr. Boyd and Mr. Wyeth fell in.”

After the new year, Wyeth began work on his Drums illustrations. In addition to the set of 17 paintings, he agreed to render a number of pen drawings for the new edition. On Jan. 5, 1928, he reported to Boyd on his progress or lack of same. “I am not taking easily to this medium for it is years since I have handled it,” he wrote. “Have done about twenty which I destroyed this morning and feel better for it.”

Wyeth’s message expressed agonized frustration concerning his work, startling when coming from the greatest illustrator alive. “How I do yearn for the technical ability to put down in color and pattern the things that are almost tearing my insides out,” he wrote.

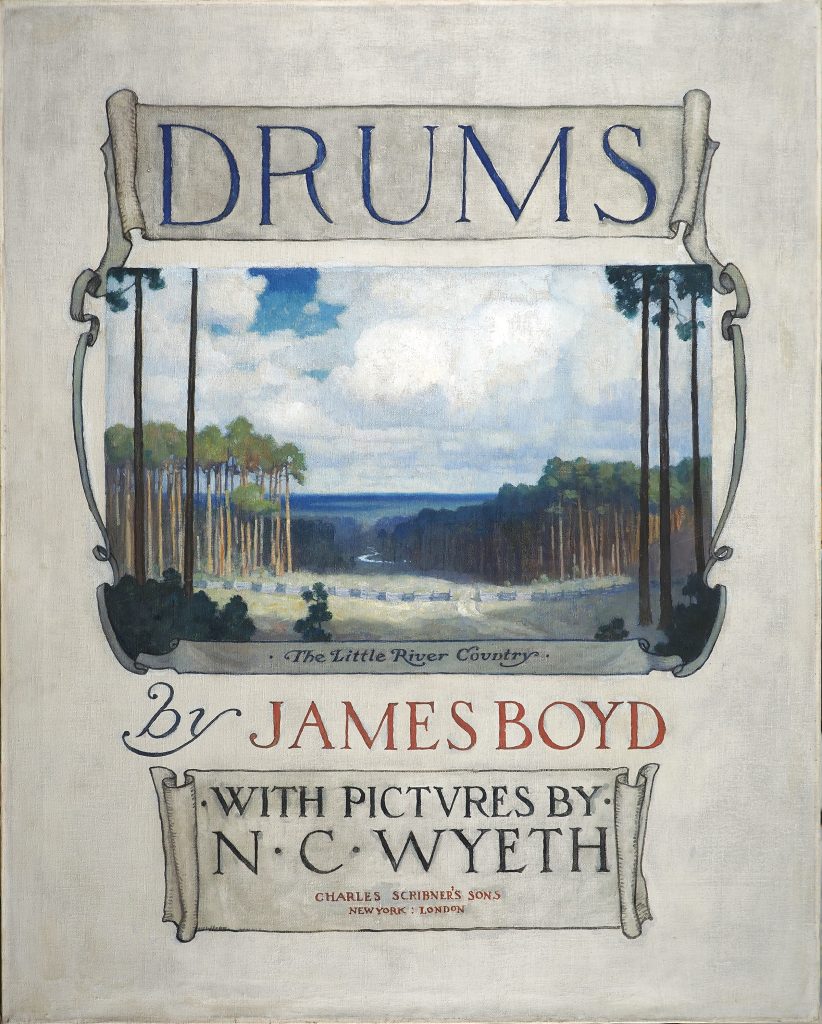

The 17 illustrations for Drums included several of high drama like “The Fight at the Foretop” aboard the Bonhomme Richard; “The Horse Race” (which Johnny won); “Johnny’s Defeat at the Dock,” when he was treated roughly in Edenton; and “Captain Tennant,” where the British official cooly confronts the crowd demanding his departure. Others like “The Fraser Family,” depicting young Johnny and his parents riding their old chaise to church; and “The Mother of John Paul Jones” lack drama, but help the reader visualize the characters. The Drums title page illustration includes a pastoral landscape, supposedly portraying the Little River Country, though it actually came from a Chadds Ford area view.

Though their effusive correspondence suggests an exceedingly collegial friendship, there is no record of further dealings between Boyd and Wyeth following the 1928 publication of the Illustrated Classics edition of Drums, which sold exceedingly well. It’s hard to imagine, however, that they didn’t see one another during the Yuletide stay of Wyeth and his wife, Carol, at Southern Pines’ Highland Pines Inn in 1931 (reported by The Outlook on Dec. 19 of that year). There is no mention there or elsewhere, that the Boyds and Wyeths saw one another. By contrast, Boyd’s hobnobs in Southern Pines with other revered men of the arts like F. Scott Fitzgerald, Thomas Wolfe and John Galsworthy were copiously reported. It’s puzzling.

Even if they did not meet during that visit, the two men presumably had further contact because Boyd wound up acquiring three of the 17 canvases Wyeth painted for Drums: the “Title Page” illustration; “The Fraser Family” painting; and “Captain Tennant.” Those canvases are currently on display at the Weymouth Center for the Arts & Humanities as part of its Celebration of Drums. This year marks the centennial of the novel’s initial publication. The Wyeth paintings are on loan from the town of Southern Pines, which now owns them.

But what were the circumstances of Boyd’s acquisition of the illustrations? When did he take possession of them? Was it possible he got them from Scribner’s instead of Wyeth? Did Boyd purchase the paintings, or were they a gift?

The earliest mention referencing Boyd’s ownership of the illustrations came from a Dec. 7, 1939 Outlook blurb. It read: “Above the fireplace in the Southern Pines Library are two of the original N.C. Wyeth illustrations used in depicting scenes in Mr. James Boyd’s book, Drums. These interesting illustrations, on display through the courtesy of Mr. Boyd, add much color and charm to the reading room of the library.” (The library was then located on Connecticut Avenue and operated independently by the Southern Pines Library Association.)

Michaelis’ biography makes it clear that Boyd obtained the paintings from Wyeth. During N.C.’s early work for Scribner’s, he was squeamish about speaking up for himself, and the publisher kept most of his paintings. Over time, however, he became more forceful in negotiations with the publisher. By 1920, Scribner’s was returning all of Wyeth’s canvases to the artist. A check of Scribner’s archival records confirmed the company sent the Drums illustrations back to Wyeth.

Whether the artist sold or gifted the illustrations to Boyd is a more complicated issue. The fact that Wyeth had previously sent a picture of one illustration to Boyd “thinking it might interest you,” seemed the sort of thing a seller might say to kick off negotiations. But a scouring of Boyd’s personal papers at the University of North Carolina’s Wilson Library revealed no support for this theory. Carrie Hays, administrative coordinator for the town of Southern Pines, compiled background information concerning the paintings, but nothing relates to how Boyd obtained them from Wyeth.

N.C.’s great-granddaughter, Victoria Wyeth, speaks regularly concerning her legendary family’s legacy. (She was featured in Ray Owen’s October 2018 PineStraw article “America’s First Family of Art.”) While Victoria had no information concerning her great-grandfather’s disposition of the paintings, she graciously put me in touch with folks who did at the Brandywine Museum of Art in Chadds Ford.

The museum includes Wyeth’s studio and holds a treasure trove of his paintings along with records of their provenance. Amanda Burdan, the senior curator of the museum, provided valuable, though not conclusive, insight on the issue. “It is most likely that he (Wyeth) sold those three paintings to (Boyd) directly,” she said. “He did occasionally gift paintings, but it tended to be for special occasions like weddings of friends.” Burdan said that “several of the Drums illustrations stayed with the Wyeth family until well after N.C. died in 1945.”

Burdan and her assistant, Lillian Kinney, took a look at Wyeth’s tax records in hopes they might reveal income from sales of illustrations to third parties. There was some, but the records were inconclusive — another rabbit hole.

Sandy Gernhart is the archivist for the Weymouth Center, which houses many Boyd documents. She found a 2005 Weymouth inventory binder that indicates Wyeth gifted the illustrations to Boyd. According to Gernhart — and prior Weymouth Center historian Dotty Starling — it has through the years been “known” at Weymouth that the illustrations came to Boyd by way of a gift from Wyeth. Both women concede there is no documentation, aside from the non-contemporaneous inventory binder, that backs up this lore.

Nonetheless, the apparent closeness of the two kindred spirits during their time together and the generous hospitality exhibited by the Boyds to Wyeth provide strong circumstantial evidence supporting the likelihood of Wyeth’s tendering such a generous gift.

How did the town of Southern Pines eventually obtain ownership of the illustrations? After World War II, the town constructed a new edifice on Broad Street that would house the library — now the home of the town’s utilities office. Soon thereafter, the library came under the town’s umbrella. A wing was added to the structure in 1948 that was dedicated to the memory of James Boyd, who had passed away in 1944. Katharine Boyd contributed a number of historic artifacts to be displayed in the James Boyd Room, including a desk purportedly used by Lincoln while he was in Congress, an autograph collection, several pieces of early American furniture, and the Wyeth illustrations.

Katharine Boyd’s 1969 will (she died in 1974) mentions nothing about the paintings, so presumably she considered them already donated to the town, perhaps when the James Boyd Room was opened in ’48. But if so, the gift, like other dealings in this account, appears to have been accomplished without written record.

The town is permitting the Weymouth Center to display the illustrations throughout most of 2026. As of now, it’s unclear where Wyeth’s illustrations will be housed once they are returned to the town.

Wherever they wind up, security will be paramount. There is no hiding the fact the canvases are valuable. N.C. Wyeth illustrations frequently sell at six figures. The highest amount paid to date is $5.99 million for his Portrait of a Farmer at a Sotheby’s auction in 2018. Wyeth, who belittled the merits and value of his own illustrations, would undoubtedly be gobsmacked at such stupefying prices.

Wyeth died in 1945, one year after Boyd, at the age of 62. His demise was both tragic and mystifying. While driving near Chadds Ford, Wyeth’s car stopped on the track at a railroad crossing. An onrushing train crashed into his auto, killing him and his 3-year-old grandchild. Why Wyeth was stopped on the track remains an unknown.

While a bit of mystery lingers regarding the Wyeth-Boyd relationship and the three illustrations, there is none concerning Wyeth’s artistic greatness. Though in the grand sweep of time the regard given to the works of Boyd and Wyeth may have traveled in different directions, their association, while brief, made for a memorable collaboration.