Simple Life

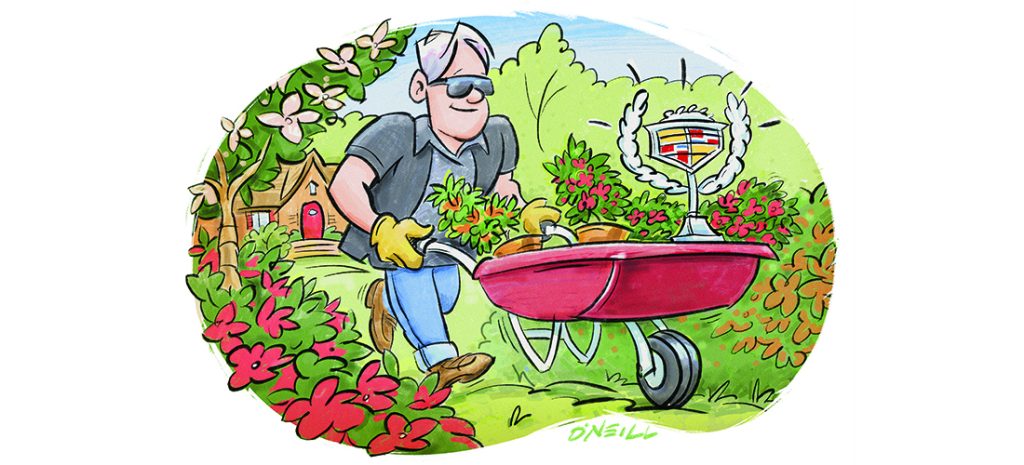

Cadillac Joe

While some of his dogwoods are long gone, the legend lives on

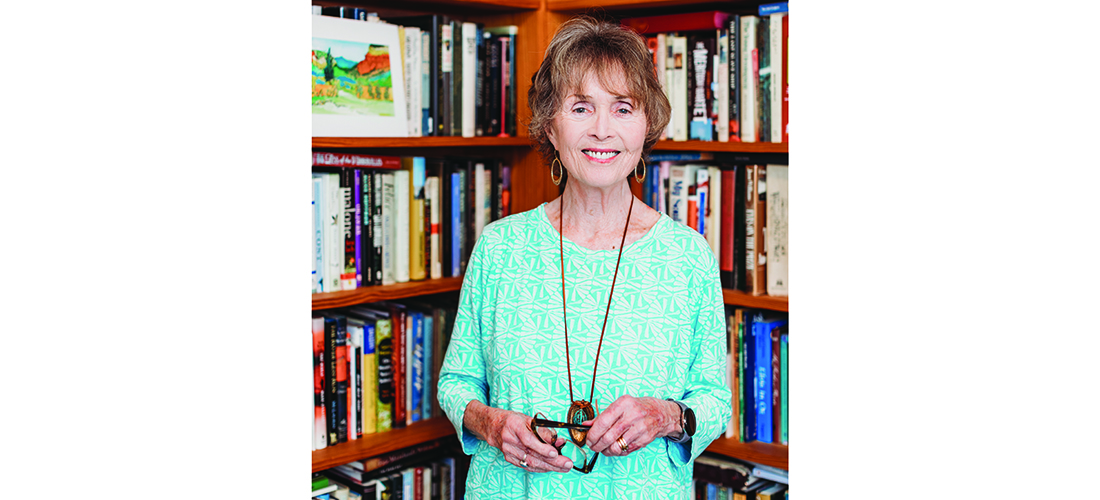

By Jim Dodson

As spring broke this year, I had a startling realization.

I may be turning into Cadillac Joe.

His real name was Joe Franks. Mr. Franks and his delightful wife, Ginny, and their two boys, Joe Jr. and Chuck, lived across the street in the old neighborhood where I grew up. I was good friends with the Franks boys. My mom was one of Ginny Franks’ closest chums.

Big Joe was a highly respected lawyer in town, though that’s not what made him something of a local legend.

Every spring, the Franks family lawn burst spectacularly into bloom with luscious beds of mature azalea bushes Joe had planted and groomed. During the peak blooming stage, usually around Easter, a constant stream of cars cruised slowly past his house just to take in the impressive floral show — rather like people do at Christmastime to look at over-the-top lighting displays. And thanks to several hundred pink and white dogwood trees that bloomed along the street just as the Franks’ yard exploded in color, Dogwood Drive lived up to its name, including a magnificent Cherokee Brave (pink) and Cherokee Princess (white) that proudly stood for more than half a century.

Over the years, our street — and the Franks house in particular — found their way into numerous newspaper feature sections and a host of top gardening magazines, including a couple big spreads in Southern Living magazine.

What made the show bigger than life was that most Sunday mornings throughout spring and summer, Big Joe Franks lovingly washed or waxed his Cadillac in the Franks family driveway while playing the music of Frank Sinatra. His neighbors must have been fans of Ol’ Blue Eyes because nobody I know of ever complained. My mom even took to calling him Cadillac Joe. Looking back, I’m half convinced Cadillac Joe’s music is the reason I have a thing for Sinatra today.

“Dad sure loved that Cadillac and his azaleas,” Joe Jr. confirmed with a booming laugh when I tracked him down by phone. “And, of course, Sinatra. That was the music of his life. Waxing that Cadillac and growing those azaleas were his passions.”

Joe, the son, is something of a legend, too. He grew up to become a beloved athletic trainer and successful men’s football and women’s golf coach at Grimsley High School. The playing field at Jamieson Stadium is named for “Little Joe Franks,” as my mom called him. Today, Little Joe is semi-retired and lives in Danville, Virginia, where his wife, Dr. Tiffany McKillip Franks, is in her 14th year as president of Averett University.

“So how are your azalea bushes doing?” I asked him.

“The college has plenty of them. I don’t have my dad’s thing for growing them, but I do have a Cadillac Escalade just like Dad. And I recently picked up a second one, an ATS two-door coup. Really nice.”

I wondered if Joe had any idea how many azalea bushes his dad, who passed away in 2001, planted and groomed to perfection.

“At least 250,” Joe said, explaining how Big Joe’s favorites were red, white and pink azaleas. “If you recall,” he added, “there was a huge peach-colored one by the front porch. It was probably seven or eight feet tall.”

I remembered this bush and almost hated to inform him that the bright young college professor who owns the Franks house today is growing artichokes where Cadillac Joe worked his magic each spring.

“Yeah, by the time my mom was ready to give up the house,” Coach Joe told me, “the plants were showing their age and had probably seen their better days. I guess they just dug them up.”

“Don’t worry,” I said, pleased to inform him. “I think I might be channeling Cadillac Joe these days.”

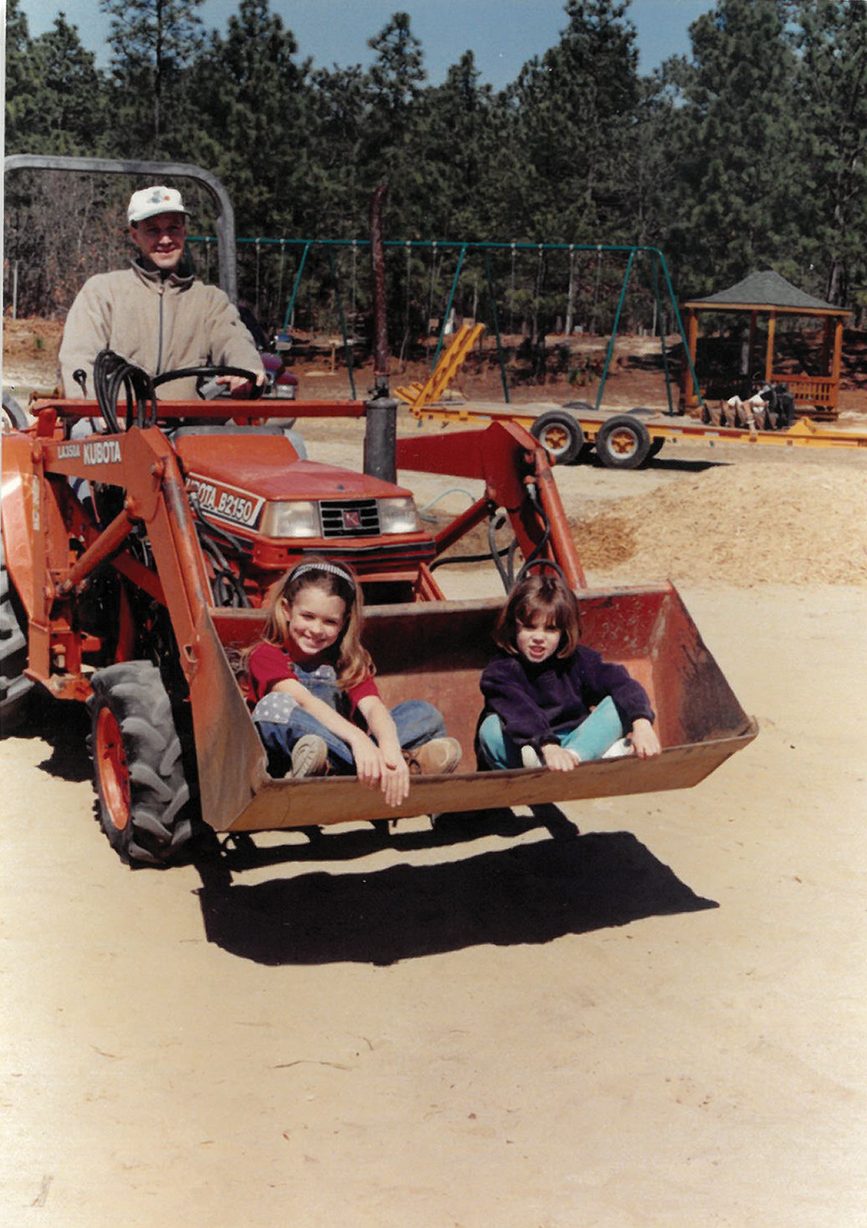

Six years ago, my wife, Wendy, and I moved back to Dogwood Drive, purchasing an old house that sits two doors from the one where I grew up. As she got to work restoring the house’s interior, I got to work outside. To date, I’ve planted more than 30 trees in my yard, including five dogwoods, a trio of southern redbuds and several cherry trees that outrageously bloom every spring. I’ve also planted 24 azaleas and 17 hydrangeas.

A garden-loving psychologist wouldn’t be wrong in suggesting that I’m rebuilding the blooming street of my boyhood. I hail from an old Carolina clan of farmers, gardeners, preachers and storytellers, after all, and grew up hearing legends of the dogwood tree’s origin, one of which holds that long ago the dogwood was a mighty tree — like the oak — that was used to make the cross on which Jesus was crucified. Because of its role in the death of Christ, the legend goes, God both cursed and blessed the little tree. It would never again grow large enough to be used as a cross for a crucifixion. Yet it would also produce beautiful flowers in the spring, just in time for Easter, with petals shaped like a cross, clustered berries resembling a crown of thorns and specks of red that symbolized drops of blood.

Over the half a century since I’d lived on our street, most of the dogwoods disappeared from yards. In fairness, dogwoods generally only live anywhere from 40–70 years, and the beauties I remember were probably at least already middle-aged. Even so, we count no more than 15 dogwood trees on the entire street.

For that matter, azaleas are also dramatically thin on the ground these days. Maybe they are just too finicky for casual gardeners and the new generation of busy young families that inhabit the neighborhood to keep up with, requiring annual trimming, fertilizing and mulching in order to flourish.

In truth, I was never terribly keen on planting dogwood trees and azaleas bushes until we moved back to Dogwood Drive, at which point a mysterious desire overtook me. Perhaps I am becoming Cadillac Joe 2.0?

Little Joe Franks was pleased when I mentioned this botanical phenomenon.

“That’s great,” he said. “Now all you need is an old Cadillac and the music of Sinatra!”

He may be right. For the moment at least, an aging Subaru and Mary Chapin Carpenter will have to suffice.

Maybe someday I will be remembered as the legend of Outback Jimmy. PS

Jim Dodson can be reached at jwdauthor@gmail.com.

M

M

National Wildflower Week, celebrated during the first full week of May, is spring at its finest. The air is sweet. Roadsides and meadows are bursting with life and color. The pollinators are here for the party.

National Wildflower Week, celebrated during the first full week of May, is spring at its finest. The air is sweet. Roadsides and meadows are bursting with life and color. The pollinators are here for the party.