Revitalizing West Southern Pines

By Ann Petersen

Feature Photo caption: West Southern Pines Rosenwald School, 1925

Blanchie Carter Discovery Park today

Photograph by John gessner

The land tells its own story. Hope, creativity and adaptability are its chapters. History is alive at 1250 West New York Avenue.

In 1923, the town of West Southern Pines was chartered as one of the first African American townships on the East Coast. Jim Town was the slang expression for it in those days, either in reference to James Bethea, who owned the general store and other property in the new township; or because of the Jim Crow laws of the day, explains Kim Wade, an expert on West Southern Pines’ history.

The citizens of the new township, often earning as little as 50 cents a day, dreamed of building a Rosenwald School to ensure their children’s education. Julius Rosenwald, the co-owner of Sears, Roebuck and Company, and his wife, Augusta, Jewish immigrants from Germany, established the Rosenwald Fund in 1917 “for the betterment of mankind.” Among its contributions, the Rosenwald Fund (in common cause with Booker T. Washington) helped build schools in an effort to strengthen rural Black communities in the United States.

With little more than hope to drive their funding, the community raised $6,000, above and beyond municipal taxes, to match the grant from the Rosenwald Fund. Four acres were donated by William and Emma Junge as a site for the school. The land was cleared by the community, and the school was completed in 1925. In the 1940s the Rosenwald School gave way to a more modern structure, and the property became West Southern Pines High School. While the name implied the school was for students in higher grades of secondary education, it was actually the school all children of color attended, regardless of age or grade level. Though the town charter was rescinded in 1931, the community, and school, strove to maintain their viability. A gym and lunchroom along with multiple wings of classrooms were added.

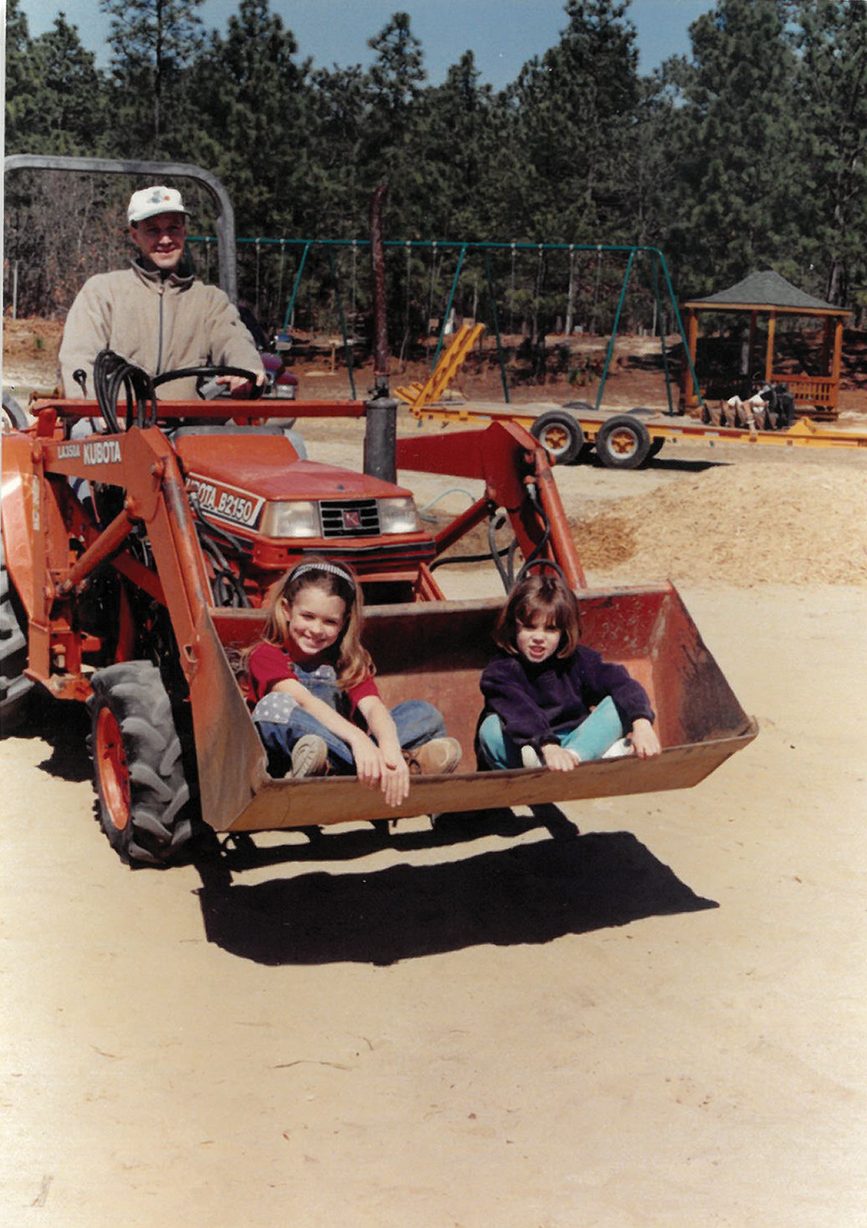

Work and play at the Blanchie Carter Discovery Park, 1998

Photographs Courtesy Ann Petersen

Many West Southern Pines alumni are still in Moore County. Some, after living successful lives elsewhere, have circled back home. Dorothy Brower, a member of the high school’s last graduating class, is just one example. She returned after a career that included being the director of the Orange County Campus of Durham Technical Community College and the affirmative action officer. Other alumni include Shirley Bowman, Dorothy Douglas Jackson, Walter Powell, Martha Dickerson, Jennifer McCall, Carolyn Penland, Bill Ross and Tessie Taylor.

Retired Lt. Col. Vincent Gordon came back after his stint in the service, followed by his work as an administrative officer with the census bureau in Washington, D.C. When Gordon, one of four sons of a school principal and a Moore County Schools teacher, returned, he was armed with the kind of experience that would prove invaluable when 1250 New York Avenue eventually transitioned to the Southern Pines Housing and Land Trust.

In the 1960s, it was the hope of then-Superintendent Bob Lee to desegregate Moore County Schools and create a heterogenous school system with equal access to education, regardless of race. While Lee and his family endured hateful threats, he worked tirelessly to achieve that goal. With the support of a fearless school board, the dream became a reality and, with desegregation, West Southern Pines High School would become Southern Pines Elementary School.

In 1995, my eldest daughter, Katie, was 5 years old, and my husband, Bruce, and I hoped for what all parents desire: a creative, inspiring, sound education for our children; an education where they would be loved and nurtured. Our decision ultimately fell to Katie and her soon-to-be principal, Blanchie Carter.

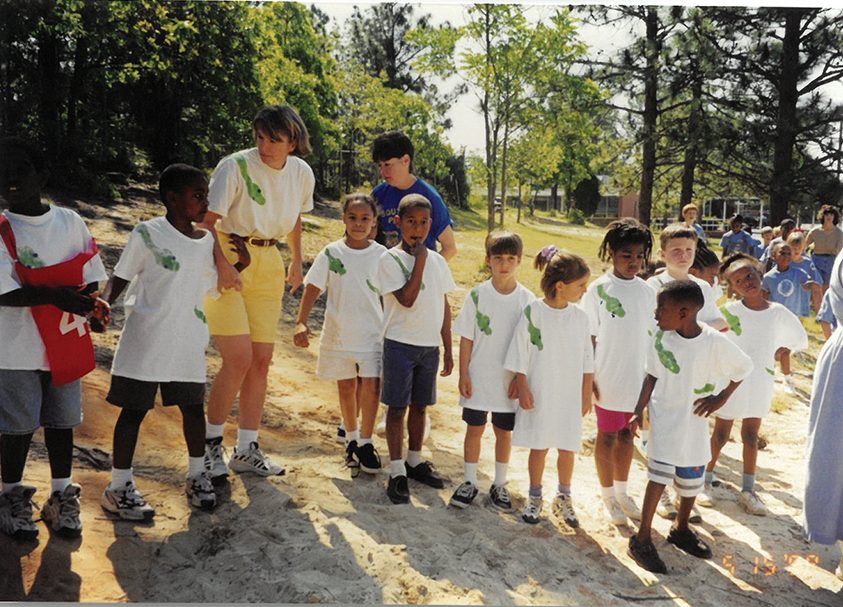

Work and play at the Blanchie Carter Discovery Park, 1998

Photographs Courtesy Ann Petersen

I remember walking through the halls of Southern Pines Elementary, trailing behind Blanchie and Katie. As Bruce and I checked out the surroundings, our loquacious child peppered Blanchie with comments and questions. When we reached the media center Katie turned to us and announced: “This will be my school.” And it was.

There was one drawback to the school at that time. The playground was a treeless desert, a home to unrelenting heat in the late summer and blistering winds in the winter. Periodic dust tornadoes would flit across the barren land. It was a place that bred anger and frustration for the students and the teachers. Riddled with sand spurs, the playground made recess, meant to be a healthy break in the day, anything but. It was, instead, a time to endure.

I signed up to co-chair the playground committee for the PTA. Our goal was to raise $25,000. Bruce, as he was prone to do, signed on to help. We ended up raising 10 times that amount. Fueled by both hope and good luck, we started searching for someone with expertise to help us with the playground. We discovered one of the world’s premier designers of parks for children, an Englishman, was on the teaching staff at the N.C. State School of Design.

Enter Robin Moore. His first lesson was to teach us we were not building a playground, but rather a discovery park. He was right. Blanchie Carter Discovery Park was born.

Moore led us to Dr. Nilda Cosco, a native Argentinian who is an expert on learning through play, also on the faculty of the N.C. State School of Design. She earned her reputation as a leader in the field by working with economically, physically and mentally challenged children in Buenos Aires. I like to think there is a magical matchmaking component to the Blanchie Carter Discovery Park. Shortly after Moore and Cosco began to collaborate on the park in West Southern Pines, Bruce and I received notice of their marriage.

Work and play at the Blanchie Carter Discovery Park, 1998

Photographs Courtesy Ann Petersen

By 2006 the Blanchie Carter Discovery Park was built. The New York Times ran a feature on the park. Southern Living magazine came calling. Students read about the park in their national Scholastic magazines. James “Pygie” Pugh showed up with his D-6 bulldozer to cut the peripheral trail. Interns came from England to work with the students. Hope and curiosity had carried the day.

Mary Scott Harrison, the principal of the school following Blanchie’s retirement, recognized the extraordinary benefit the park served. Discipline problems dissipated. Both students and teachers were happier. Teachers designed lessons that could be taught outdoors. The school nurse created a walking club that met each morning and walked the peripheral trail.

The staff at Southern Pines Elementary School was as good as any in the country. With the likes of Elaine Simon, Barbara Kelly (Smith), Mamie Allen, Damita Nocton, Edith Moore, Annie Osterman, Liz Lyndsey, Elizabeth Strickland, Toni Hyman and Jane Kschinka, led first by Blanchie Carter and then by Mary Scott Harrison, children thrived. Four years after Katie enrolled at the school, Jennie, her younger sister, entered the magic that was SPES. Jeff Moody, a retired track star turned elementary gym teacher, knew each child’s name. He could spot the gift Jennie possessed as she raced around the track. “She’s fast. Be patient and let her lead the way. She’s a runner,” he told us. Jennie’s running career, which eventually led her to Dartmouth College, began on the SPES track.

I have not cried when my children advanced from one educational level to another with one exception: I cried the day they both left 1250 West New York Avenue.

In 2020, Southern Pines Primary School (having supplanted Southern Pines Elementary School) was rendered outdated, and the property was vacated. Students of both Southern Pines Primary School and Southern Pines Elementary School enrolled in their brand new school on Carlisle Street. With that change, the land readied for another new chapter.

Bruce Cunningham working on the Blanchie Carter Discovery Park, 1998

The school board offered the land up for sale. There were struggles as the community sought to, again, purchase the land. As stories have a way of doing, this one came full circle when the land, primed for a new beginning, became the property of the Southern Pines Housing and Land Trust, an effort led by Vincent Gordon.

The purchase was driven largely by descendants of those who had attended the original Rosenwald School who hoped to not only embrace the history of the land, but to preserve Blanchie Carter Discovery Park as a learning venue for all children of Southern Pines to visit and enjoy. The final payment for the land was made by the Town of Southern Pines. Council member Mike Saulnier, who understood the importance of preserving the park, gave birth to a solution that resulted in a contract between the town and the Land Trust.

The former school now proudly houses the West Southern Pines Center for African American History, Cultural Arts and Business. But hopes and dreams need funding to be realized. With a strong board of directors; Executive Director Sandra Dales; Director of Operations Nora Bowman; the relentless efforts of Tom, Lori and Rachel Van Camp; and an army of volunteers led by Susan Ward, who has managed the maintenance of the park, the weekend of May 19-20 will be filled with events to further the goals of refurbishing both the auditorium and Blanchie Carter Discovery Park.

On May 19, the auditorium where I once watched colorful Christmas pageants will play host to a jazz concert featuring Nnenna Freelon, a seven-time Grammy nominee. Tickets are on sale now at ticketmesandhills.com. With luck, similar fundraisers will become annual events. There will be an invitation-only dinner and auction on May 20 recognizing the contributions of the community, including businesses like the Pinehurst Resort, First Citizens Bank, First Bank and The Friends of the Pinehurst Surgical Clinic. Attendance will likely exceed 350.

Hope has never left 1250 West New York Avenue. Some hope for a museum that embraces the history of West Southern Pines. Others hope for a commercial revitalization of businesses there. A youth basketball team meets in the gym to practice, and the players hope for victory while their coaches — who refinished the gym floor themselves — hope the young players will learn the lessons of collaboration and teamwork. Moore and Cosco have returned to work on the rebirth of the Discovery Park, hoping the land will not only enhance the lives of local children, but serve as a training center for teachers studying early childhood development. It remains a place where dreams can come true. PS

Bruce Cunningham and Ann Petersen were awarded the Governor’s Volunteer Award for their work on the Blanchie Carter Discovery Park.