March Bookshelf

March Books

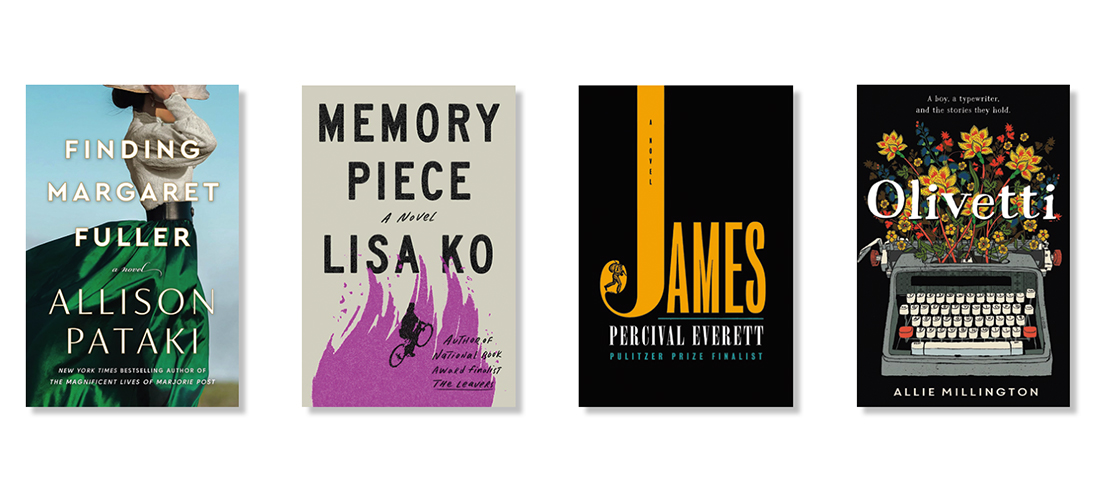

FICTION

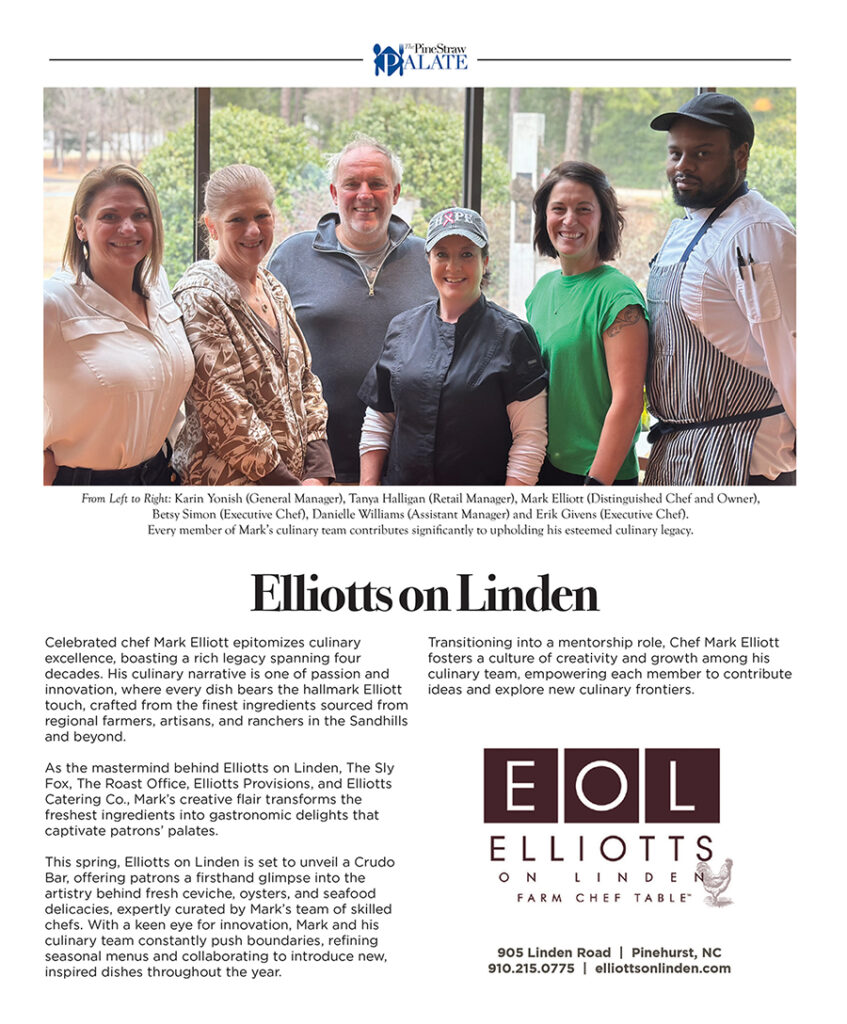

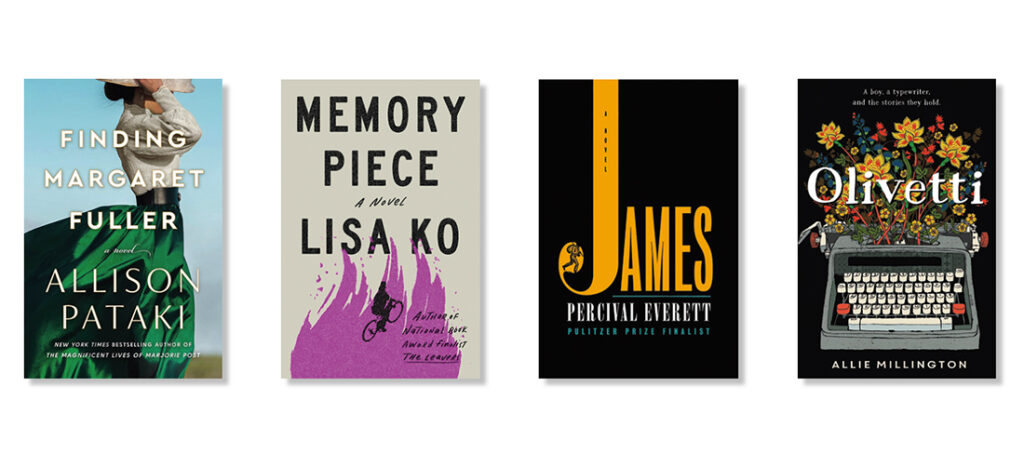

Finding Margaret Fuller, by Allison Pataki

Young, brazen, beautiful and unapologetically brilliant, Margaret Fuller accepts an invitation from Ralph Waldo Emerson, the celebrated Sage of Concord, to meet his coterie of enlightened friends. There she becomes “the radiant genius and fiery heart” of the Transcendentalists, a role model to a young Louisa May Alcott, an inspiration for Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Hester Prynne and the scandalous Scarlet Letter, a friend to Henry David Thoreau as he ventures out to Walden Pond . . . and a muse to Emerson. From Boston to the gritty streets of New York she defies conventions time and again. When the legendary editor Horace Greeley offers her an assignment in Europe, Margaret makes history as the first female foreign news correspondent, mingling with luminaries like Frédéric Chopin, William Wordsworth, George Sand and others. In Rome she finds a world of passion, romance and revolution, taking a Roman count as a lover — and sparking an international scandal. With a star-studded cast of characters and sweeping, epic historical events, this is a story of an inspiring trailblazer, a woman who loved big and lived even bigger.

Memory Piece, by Lisa Ko

In the early 1980s, Giselle Chin, Jackie Ong and Ellen Ng are three teenagers drawn together by their shared sense of alienation and desire for something different. “Allied in the weirdest parts of themselves,” they envision each other as artistic collaborators and embark on a future defined by freedom and creativity. By the time they are adults, their dreams are murkier. As a performance artist, Giselle must navigate an elite social world she never conceived of. As a coder thrilled by the internet’s early egalitarian promise, Jackie must contend with its more sinister shift toward monetization and surveillance. And as a community activist, Ellen confronts the increasing gentrification and policing overwhelming her New York City neighborhood. Over time their friendship matures and changes, their definitions of success become complicated, and their sense of what matters evolves. Memory Piece is an innovative and audacious story of three lifelong friends as they strive to build satisfying lives in a world that turns out to be radically different from the one they were promised.

James, by Percival Everett

When the enslaved Jim overhears that he is about to be sold to a man in New Orleans, separated from his wife and daughter forever, he decides to hide on nearby Jackson Island until he can formulate a plan. Meanwhile, Huck Finn has faked his own death to escape his violent father, recently returned to town. As all readers of American literature know, thus begins the dangerous and transcendent journey by raft down the Mississippi River toward the elusive and too-often-unreliable promise of the Free States and beyond. While many narrative set pieces of Adventures of Huckleberry Finn remain in place, Jim’s agency, intelligence and compassion are shown in a radically new light. Brimming with electrifying humor and lacerating observations James is destined to be a cornerstone of 21st century American literature.

Olivetti, by Allie Millington

Being a typewriter is not as easy as it looks. Surrounded by books (notorious attention hogs) and recently replaced by a computer, Olivetti has been forgotten by the Brindle family — the family he’s lived with for years. The Brindles are busy humans, apart from 12-year-old Ernest, who would rather be left alone with his collection of Oxford English Dictionaries. The least they could do was remember Olivetti once in a while, since he remembers every word they’ve typed on him. It’s a thankless job, keeping memories alive. Olivetti gets a rare glimpse of action from Ernest’s mom, Beatrice, only for her to drop him off at Heartland Pawn Shop and leave him helplessly behind. When Olivetti learns Beatrice has mysteriously gone missing afterward, he believes he can help find her. He breaks the only rule of the “typewriterly code” and types back to Ernest, divulging Beatrice’s memories stored inside him. As Olivetti spills out the past, Ernest is forced to face what he and his family have been running from, The Everything That Happened.

CHILDREN’S BOOKS

Luigi, The Spider Who Wanted to Be a Kitten, by Michelle Knudsen

Oh, Luigi. The temptation of tasty breakfasts and getting tucked into bed have Luigi thinking kittens must live magical lives. So, a kitten he will be! But how long can he keep up this façade, and what might be at stake pretending to be something you’re not? This is a super sweet pet story from the author/illustrator team that created Library Lion. (Ages 3-6.)

Treehouse Town, by Gideon Sterer

Just below the canopy built on sticks and stilts, that’s where you’ll find treehouse town. With sunset lookout towers, nooks for books, and soft willow tree beds, treehouse town has something for everyone. Snuggle up! This sweet story with illustrations that have stories of their own is the perfect read-together. (Ages 3-7.)

Escargot and the Search for Spring, by Dashka Slater

Bonjour! It is the end of winter and time for Escargot to venture back into the world but . . . do his tentacles look a little droopy? His trail not quite so shimmery? Je suis désolé! It’s time to embrace sunshine. And flowers! And bunnies! Follow everyone’s favorite snail and enjoy the delights of spring. (Ages 2-6.) PS

Compiled by Kimberly Daniels Taws and Angie Tally.

The concept

The concept