The Little Nine faces an uncertain future

By Bill Fields

Golf courses come and go, enduring or failing at different times for different reasons, their guaranteed survival as rare as a calm day on a links. A particular nine-holer in Southern Pines, though, has been a good walk uncertain for a long time, not used for its original intent in 15 years, but also not utilized for a formal new purpose.

Known to many as the “Little Nine” of Southern Pines Golf Club — owned by Lodge 1692 of the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks since the middle of the 20th century — it has sat dormant since 2004, when tight finances in the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks caused the Elks Lodge to shut down a design that opened in the 1920s, a track that, like the club’s surviving 18 holes, is credited to legendary golf architect Donald Ross.

The Elks have negotiated with multiple potential buyers for Southern Pines Golf Club since it closed the Little Nine, most recently a proposed $3.2 million deal that fell through early last year. The result is that for more than a decade, the forsaken Little Nine property (45 acres, plus 55 acres of adjoining land) has remained valuable green space in a town that has seen lots of growth — a place for dog walkers, high school cross country runners and, after snowfalls, sledders on the steep “Suicide Hill” at the former fifth hole.

A recently formed nonprofit community group, Little Nine Conservancy (LiNC), whose leadership includes members of Lodge 1692, is hoping it can cooperate with the fraternal order to protect the land from being developed. Its plan: Purchase a conservation easement from Elks Lodge 1692 to ensure that the land is sustained as a natural buffer instead of potentially becoming crowded with residential housing.

“I just don’t want to see this become another suburb of Fayetteville,” says Little Nine Conservancy President Gus Sams, a neighboring landowner. “I moved here not to be part of that. One of the offers the Elks received was talking about putting between 200 and 400 homes on the hundred acres. Would the infrastructure even handle something like that? That density is more than double what we’ve got around the Little Nine right now.”

Bill Savoie, exalted ruler of Lodge 1692, says a sale that would have led to such heavy real estate development in the Little Nine space was “discounted very quickly” by the Elks. But he acknowledges that the status quo of de facto green space — taken for granted by some locals who falsely believe it can’t ever be built upon — isn’t a given.

“For the many years the Elks have owned the golf course, we’ve tried to be very good stewards of it and the adjoining property,” Savoie says. “We own 300 acres of land. The golf course pays for itself, but golf isn’t a business most people are going to want to buy into these days. At some point, how much longer does the lodge hold that land? What are its choices? The highest and best use comes into play.

“What I’ve said to [Little Nine Conservancy] is if the goals of that entity and the goals of the lodge are meshed, I support what they’re trying to do,” Savoie continued. “They see an opportunity to put an organization together to preserve the land as open space. I don’t think that is at direct odds with the goal of the Elks being stewards of the land.”

Although Sams, who grew up in Atlanta, and some of his fellow board members are transplants to Moore County, others such, as John Buchholz, Marian McPhaul and Marsh Smith, are Southern Pines natives who once lived close to the Elks Club.

“It’s a holy ground for kids who have grown up there,” says Smith, a Southern Pines attorney who has been involved with obtaining conservation easements at several other locations in the area over the last couple of decades. “It was a very important part of my life. In the fifth or sixth grade, I was so chubby my pants split when coach Wynn was teaching us how to do the forward roll. I got up the next day, in the dark, and decided I was going to run on the Little Nine. I couldn’t go a hundred yards without getting a stitch in my side but I kept at it, and I was a runner for 30 years.”

Buchholz, a retired Pinecrest High School teacher and still the Patriots’ cross country coach, came upon an overgrown Little Nine, grass as tall as a second-grader, shortly after the course closed. He believed the property — where he and his pickup football-playing childhood buddies were kicked off more than once by longtime SPGC head professional Andy Page — would be perfect for a 5K cross country course. He has cut a 5-foot swath through the former fairways ever since for prep races. Suicide Hill proved an unpopular part of the course with rival runners in the Sandhills Athletic Conference and was taken out of the route, but the incline remains part of the Patriots’ training regimen.

“We host most of the conference meets because this is one of the few courses on turf that’s available,” Buchholz says. “It is the best high school course in the state. I’ll match it against anyone’s.”

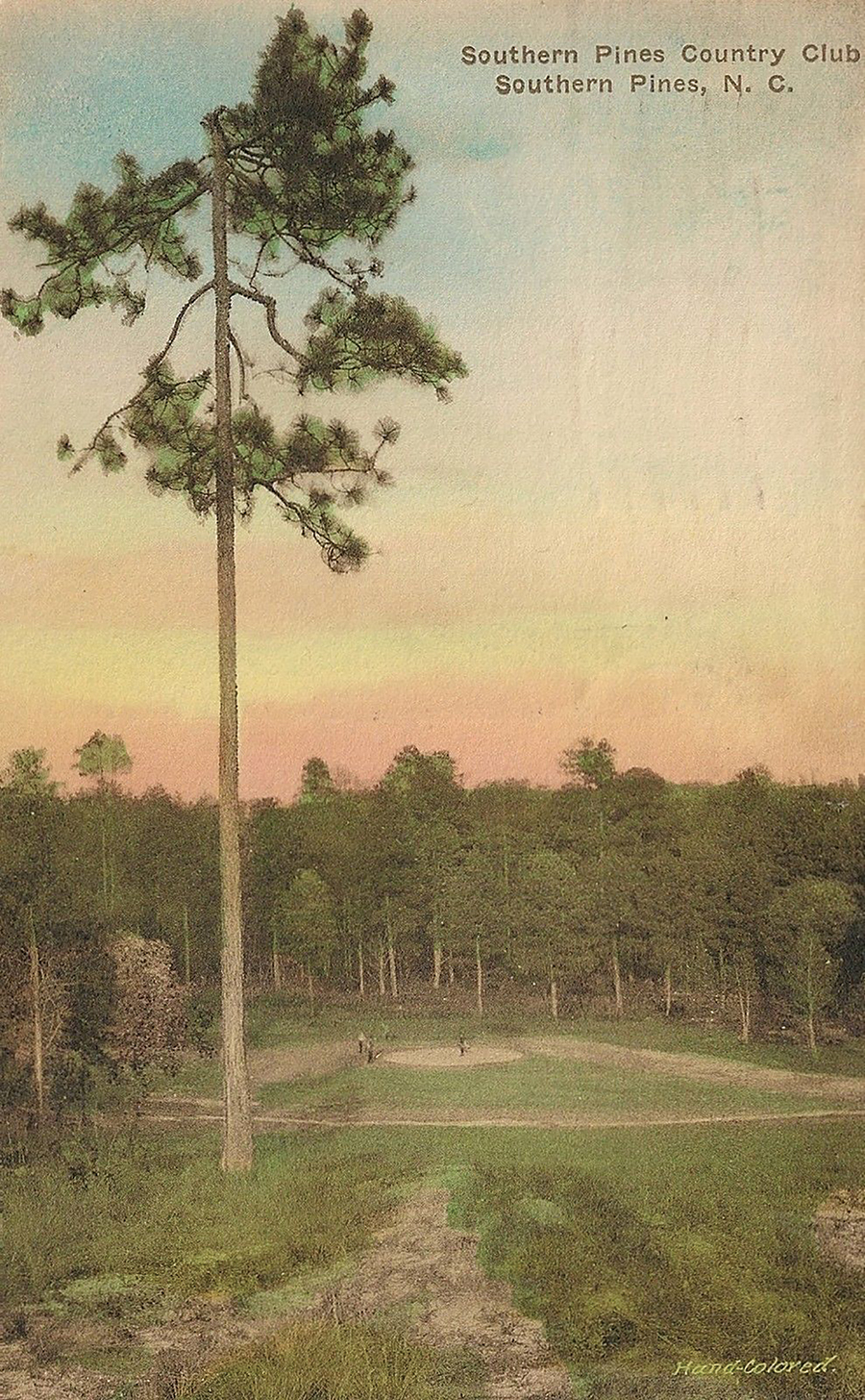

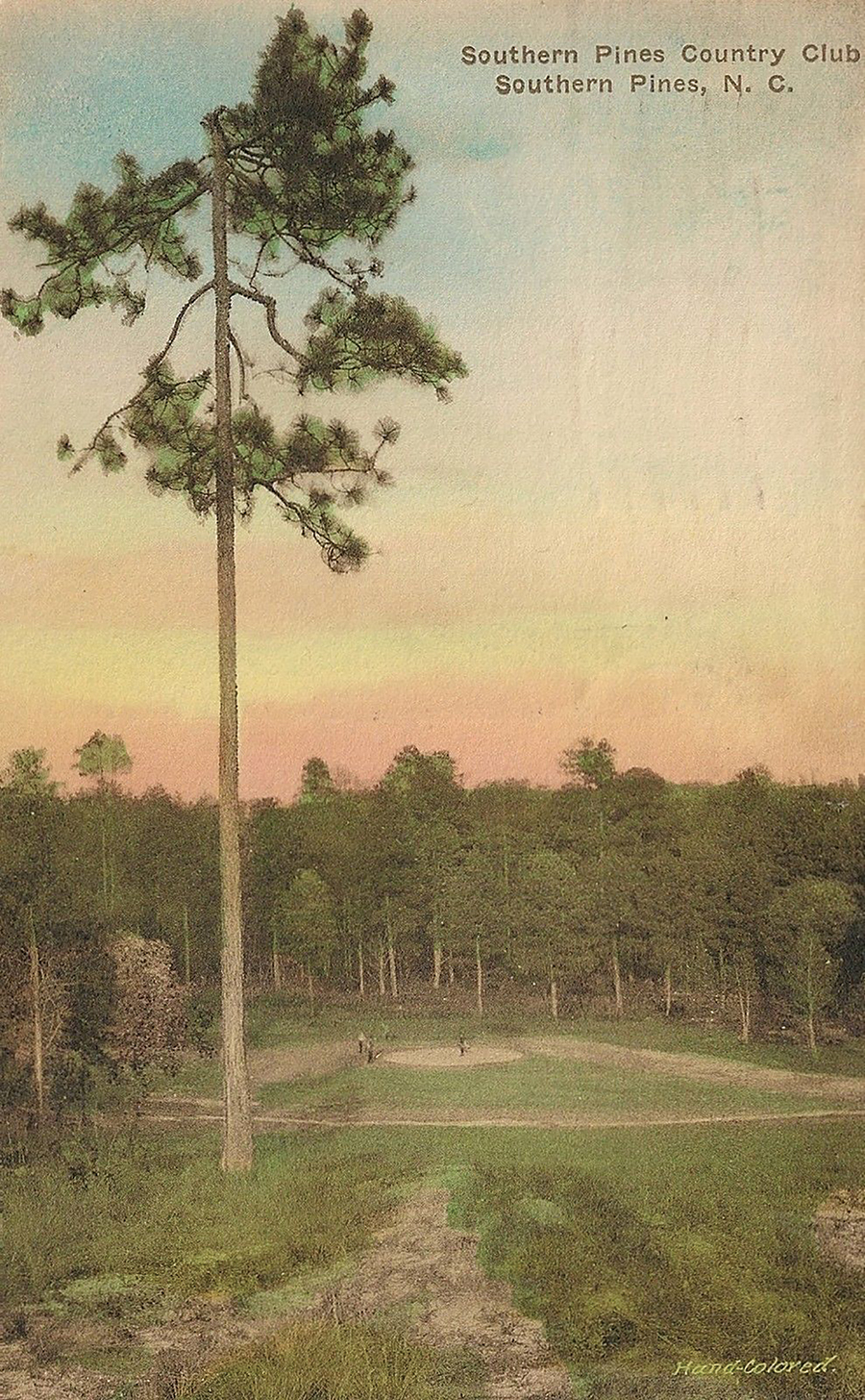

The Little Nine opened in time for the 1924 winter season, 18 years after the first holes were constructed at SPGC (then called Southern Pines Country Club) and a decade after Ross revamped the original 18 into the well-regarded layout that exists today.

“I’m long on record on Golf Club Atlas saying the main 18 at the Elks occupies the best land in Moore County [for golf], and people parrot that back to me in agreement,” says Ran Morrissett, founder of the website for golf architecture aficionados, and a Southern Pines resident and Elks Club member since 2000. “The detail work, the bones of the Ross routing, the fact that you only see homes on a couple of holes — it’s such a compelling environment.”

The third nine, to accommodate a growing tourist business, was built south and east of the clubhouse. Before the 1920s were over, it had been joined by a fourth nine. In a 1930 promotional pamphlet, Ross noted 36 holes at Southern Pines. In accounts during the 1930s, local newspapers credited Ross’ engineer and draftsman, Walter Irving Johnson, with having drawn up the plans. Johnson, hired by Ross in 1920, was an important part of his operation, executing detailed drawings from the architect’s rough sketches.

“Do I see Ross features [on the Little Nine]? Not necessarily,” says Richard Mandell, Sandhills resident, golf course architect and author of The Legendary Evolution of Pinehurst, which details the arc of golf courses in the Sandhills. “Ross is one of the top five architects of all time, but there is so much stuff that he did that wasn’t inspiring because it was on a small budget, or other people did it in his name. He probably didn’t have the ability to let loose on that third nine. And who knows what was rebuilt over all the years?”

As it expanded, though, SPGC was proud of itself. “Golf Course Extended Over The Hills and Streams, And Into The Most Rugged Section of the Sandhills,” a 1928 advertisement for the club announced in The Pilot. “The hills are rugged little mountains, giving all the charm desired for a climb or a walk in the pursuit of the game or in a ramble among the pine woods, where walks and roads, and springs, and forest foliage, suggest the primeval.”

The club’s second 18 was a par 71 of 6,120 yards, and regardless of who was most responsible for it, the layout had variety: 290-yard, par-4 No. 2; 445-yard, par-4 No. 9; 635-yard, par-6 No. 14; 126-yard, par-3 No. 15, 241-yard, par-3 No. 17. Both 18s survived the Great Depression and featured grass greens by the end of the 1930s, but the next decade wasn’t kind. World War II and ownership changes contributed to the abandonment of the fourth nine, in the Hill Road area, in the late 1940s.

Twenty-seven holes plus nine more holes “that can be easily re-conditioned” and “50 large valuable building lots” were advertised for sale in June 1948 for $110,000. Almost three years later, the Southern Pines Elks bought the property for just $58,500.

Over the years, the Elks sold some of the 500 acres included in the 1951 sale. The Little Nine became a mixture of the front and back nines of the second 18 — comprised of the opening four holes of the front and closing five holes of the back, but with the monster par-6 14th, formerly a double dogleg, shortened considerably.

The Little Nine had taken on its hybrid makeup by 1958 when Page and his wife, Margaret, started their 40-year stint running the club’s golf operations. “It had quite a bit of play over the years,” Andy says. “If we were real busy, I would send folks to play it first before playing the big course. I like to play it. Older people and kids loved to play it.”

One of those kids was Southern Pines native Chris Buie, now 55, who wrote about the Sandhills’ golf history in The Early Days of Pinehurst. “My dad became an Elk specifically because of the Little Nine,” Buie says. “It was our babysitter. It was where I learned to play golf. It was $22 for the entire summer for us kids. We would be out there all the time, a gang of us playing two or three times a day. It kept us out of too much mischief.”

If the Little Nine Conservancy (www.linc-sp.org) is able to achieve its objective, current and future generations of children might continue to be able to utilize the land. Those behind the effort would have no problem if the Little Nine was reopened as a golf course, but that seems a long shot.

“Golf is still contracting in this area. There is already an oversaturation of the market,” Savoie says. “If we had the deep pockets of a Pinehurst and wanted to turn a section of that into something like The Cradle [Pinehurst Resort’s acclaimed new short course], that would be fabulous. Unfortunately, we don’t have those resources.”

“The lodge is not desperately trying to sell,” Savoie continues. “We’re not actively speaking to people about buying. I want to see if Marsh and the Little Nine Conservancy can put something together that is good for the lodge and good for the community.”

Savoie and Smith agree a conservation easement won’t be inexpensive, given the location of the land that is the focus of LiNC’s concern.

“One hundred acres of land in close to Southern Pines’ center would be of particular attraction potentially for real estate development,” Savoie says. “I think it’s going to have to be a fairly substantial amount before the Elks say we’re going to let a potential resource like that go.”

“I think it’s fair to say the Elks’ leadership has told us their preferred outcome is for this to be protected open space, but they need a fair price for it,” Smith says. “They’ve got their club’s mission, which is to help people who are in need — school kids, veterans, handicapped folks. They’re trying to raise money.”

For now, it is the Little Nine Conservancy that is in the fundraising mode. The group is reaching out to residents who live near the Little Nine and connected woodlands, and those with ties to the area who remember it before so much growth occurred.

“I come from D.C. and know what overcrowded — really heavy development and traffic — looks like,” says Robert Simmonds, the LiNC webmaster, who recently moved to Southern Pines. “We moved here specifically because of the natural surroundings. I want to do everything I can to help it stay as natural as possible. We’re all volunteers; this is a selfless, we-think-this-is-good-for-the-community effort.”

To Morrissett, maintaining the natural setting would be good for golf, keeping the character of Ross’ surviving 18 holes. “So many courses built since Ross’ death have hinged on real estate sales,” Morrissett says. “One of the reasons the Elks course is as good as it is, is that it wasn’t built with homes in mind. If the conservancy can protect the land, the course essentially will remain alone in nature, which would be very encouraging. As an Elks member, I would be horrified at the thought that somebody could buy, say, to the right of the 13th hole and start slapping up condos. If outside intrusions start to bear down on the course, a lot of the charm would unravel. As it is now, it’s kind of cocooned in there.”

Savoie, speaking for himself and not the fraternal order, concurs. “If this were to look like a mini-Myrtle Beach, then it’s going to destroy the character of the golf course,” he says. “I certainly don’t want to be the one who puts 300 houses on a historic golf course. My personal belief is that I want to make sure we can protect the contiguous property that we have.”

The Little Nine Conservancy will do what it can. “A lot of people move to the area because of its character,” says Buchholz, who graduated from East Southern Pines High School 50 years ago. “If they want to keep it, they need to step up and be active. If we don’t do something to keep some of these natural areas, we will lose it all.” PS

Southern Pines native Bill Fields, who writes about golf and other things, moved north in 1986 but hasn’t lost his accent.