Putting art in the palm of your hand

By Jim Moriarty • Photographs by Tim Sayer

With a plastic headband circling a shock of combustible red hair and a flip-down 5x magnifier in front of her eyes, Rita Ragan sits at a desk covered with what seems like a table runner of Sticky Notes and stitches art in the miniature. While it’s not exactly getting small in the way Steve Martin joked about it back in the ’70s, the road to these pieces — not much larger than your hand — stretches back at least that far. Ragan, now in her 70s herself, hasn’t exactly marched to a different drummer, she was the drummer in the band.

She was christened Nancy Marguerite Ragan but flip-flopped all of that by becoming a Buddhist after meeting the Dalai Lama in Dharamsala, India, and becoming Rita after Ronald Reagan was elected president and the inevitable first lady name game grew tiresome. A decade or so ago she decided to go small while she was living in the biggest, broadest city America has to offer, New York. “I saw an ad for a miniature show and thought I’d go. I just fell in love with all the things that can be so tiny and wonderful, how you could take a whole world and, oh, look, it’s in the palm of your hand,” she says, extending one. “At first I was just collecting things. I always thought art was something you had to have this extraordinary special ability to do — to paint or sculpt or all those things. It just never occurred to me that I could do it — but here I am.”

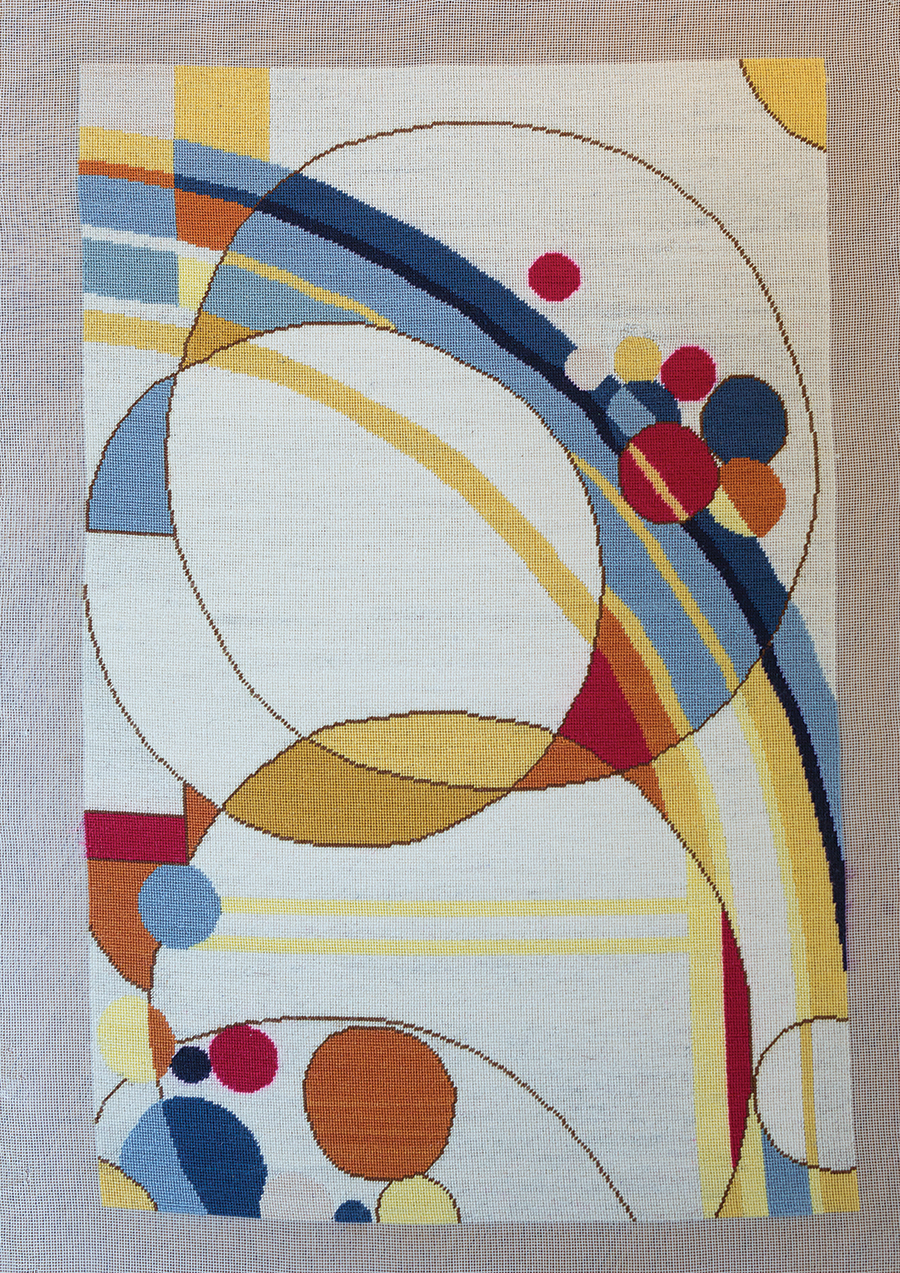

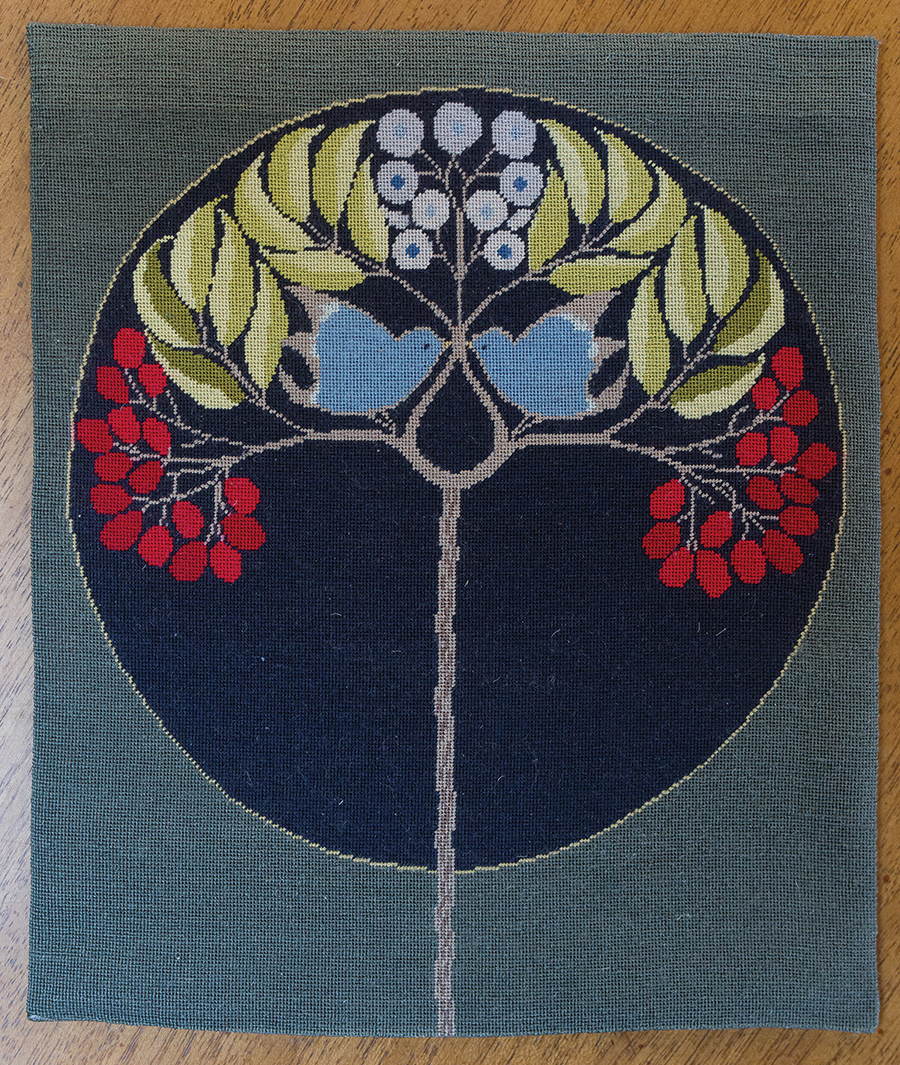

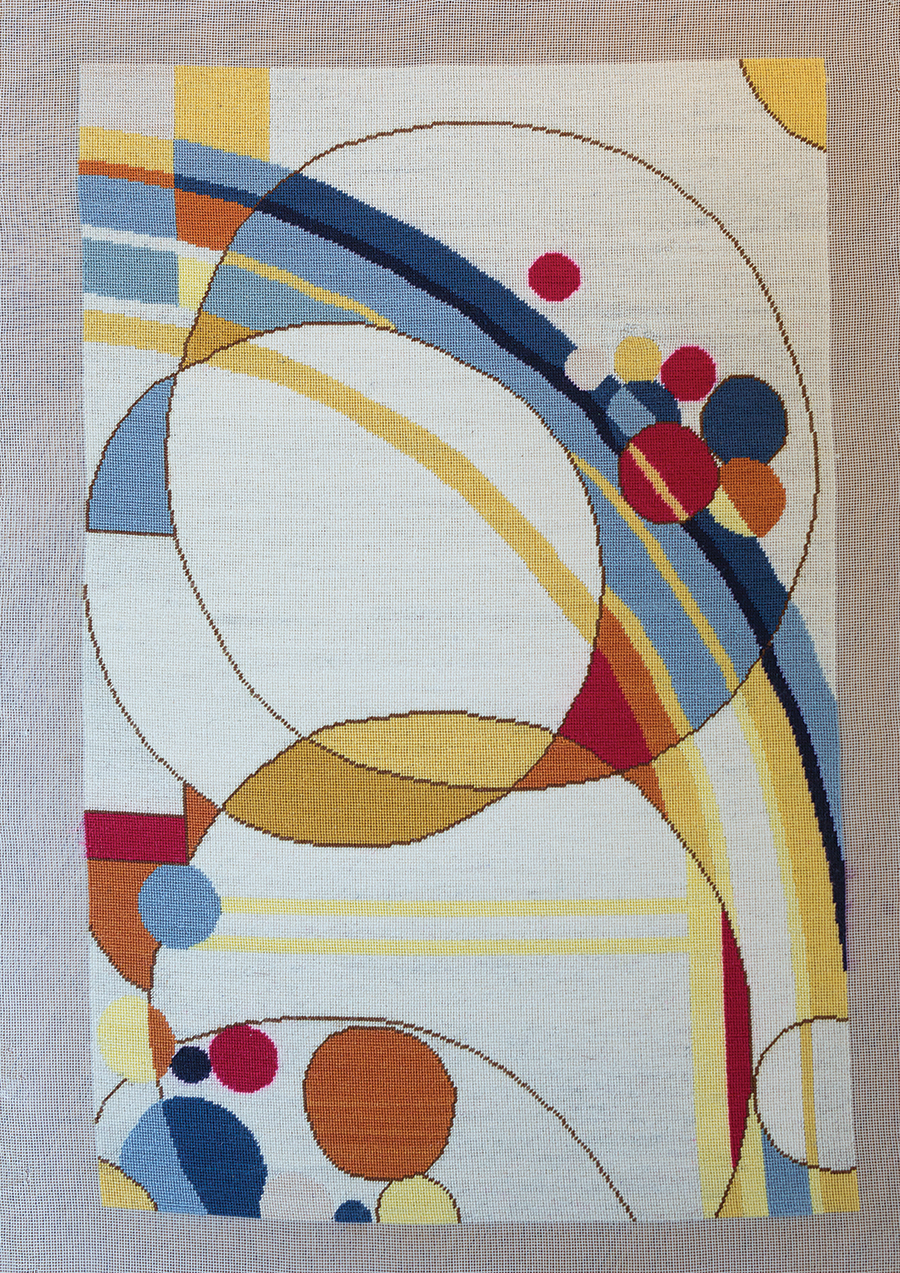

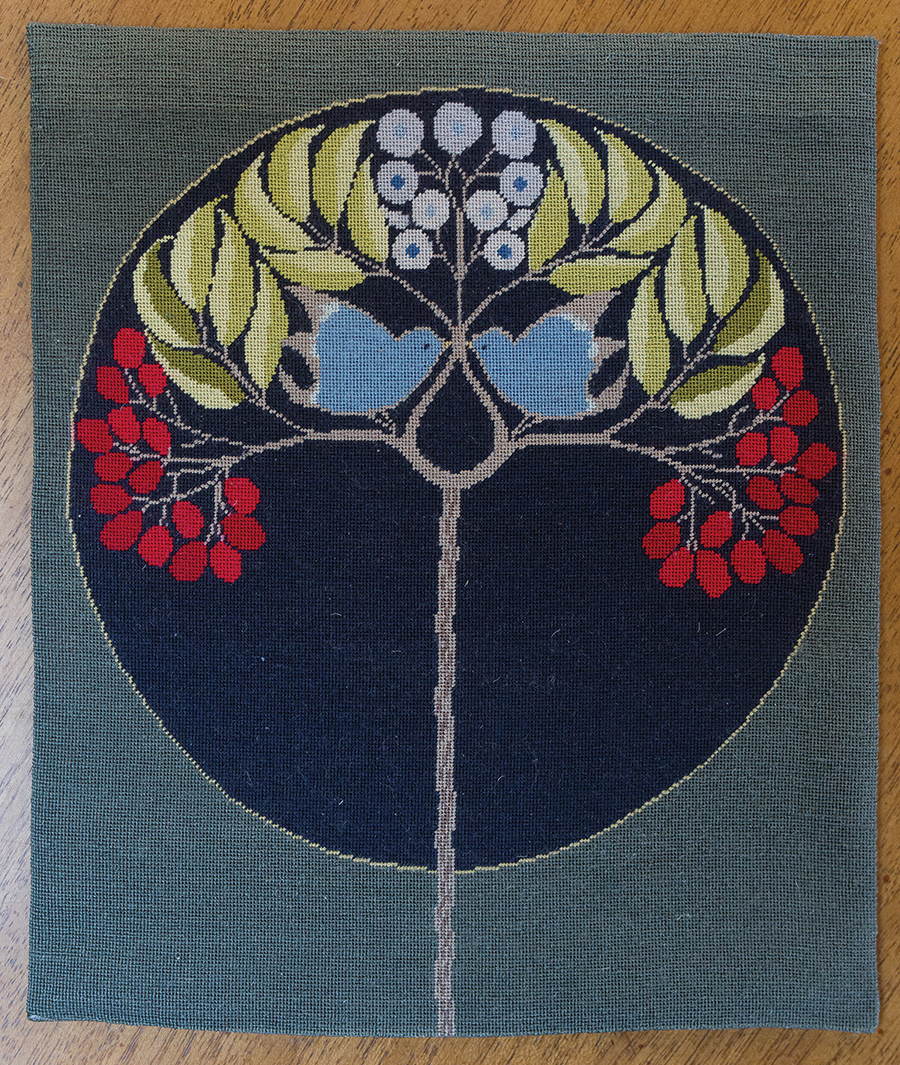

Though patterns are available, Ragan makes her own, reaching back to the ’20s and ’30s for inspiration. “It was such an exciting time. The whole world of art just went topsy-turvy,” she says. She has reproduced designs created by Frank Lloyd Wright, a painting by Henri Matisse and other images discovered as she roamed around the internet. After locating her subject, Ragan transfers it to a paper grid of her own creation with a 12 to 1 ratio to guide the otherwise freehand needlepoint. The thread she uses is 100 percent Chinese monofilament that comes in 700 different shades. There are 48 stitches to the inch, 2,304 in a square inch. “I can probably do one in six or eight weeks without going bananas. If I spend all day on it, I just get my mind fried,” she says. “But I recommend it as a hobby to anyone who likes to immerse themselves in something, let the worries of the world go away and make something beautiful.”

Ragan is the older daughter of Sam Ragan, who owned The Pilot from 1969 until his death in 1996, a man who casts as long a shadow over journalism and literature in North Carolina as the tallest pine at the Weymouth Center for the Arts and Humanities where his granddaughter, Robin Smith, is executive director and his younger daughter, Talmadge, serves on the board as chair of the N.C. Literary Hall of Fame.

“He was a lovely man,” Rita says of her father. “He always was wanting to go somewhere to see something and do something, meet interesting people.”

In this respect, at least, the pine cone didn’t fall far from the tree. “Sam thought of Mom as an adventurer, a lover of life who saw the world with the tenacious curiosity of a child,” says Robin. “He thought her brave to go after what she wanted and found her optimistic spirit contagious. I believe they were kindred spirits.”

And spirited ones. Rita, née Nancy, entered the University of Georgia at age 15, at the time the youngest student ever admitted. It only lasted a year or so until she decided to run off to New York — her first time to live there — to become an actress. It may not have been the shortest run ever on Broadway but it was in contention. The trail led back to Chapel Hill and marriage and children, Robin and Eric, and, eventually, single life again spent mostly in Vancouver, as ethnically diverse and cosmopolitan a city as any in North America.

“That’s probably the place I’ve lived the longest,” says Ragan, who, in addition to doing design work for local publications including the Vancouver Courier, became a drummer in a pair of punk rock bands, Nash Metropolitan and A Merry Cow. “We weren’t all that good, but I got to know all the other musicians in the punk scene.”

Ragan became a manager, sound technician and pre-Uber driver for the hard-edged music that crisscrossed the border from Seattle to Vancouver and back. One of the bands was The Dishrags. Though these things become a bit hazy in the long pull of time, The Dishrags were, if not the very first all-female punk rock band, in contention for the title. The group is sufficiently famous that the three band members have supplied memorabilia for a 2018 punk rock exhibit at the Canadian Museum of History in Hull, Quebec. “For some reason The Dishrags just will not die,” says their drummer, Scout (Carmen Upex), who remains close to Ragan. “We made many trips with her to Seattle,” says Scout. “We were 16 when we moved to Vancouver. She was the one who was the DD. She was responsible. She didn’t drink and she had the car.”

Let’s see, there was the vanilla colored Citroën and the blue station wagon with the push-button transmission. How many punk rockers can you get in a Rambler? “They’re usually pretty skinny, so five or six,” says Ragan. Plus gear. She also managed another influential Vancouver punk rock/new wave band called The Pointed Sticks.

In the mid-’80s and still living in Canada, Ragan was dating a guy who knew a guy (Glenn Mullin), who had lived in Dharamsala from 1972-1984 and written extensively about the Dalai Lama. In a 2015 New York Times Magazine story by Pankaj Mishra, Dharamsala is described as a rhapsodic stew of, “crimson-robed monks, longhaired travelers on motorcycles, Tibetan women in brightly striped chubas, Sikh day-trippers, Kashmiri carpet sellers and English, German and Israeli backpackers.” According to Ragan, it hadn’t changed much. Mullin introduced her to the Dalai Lama and she helped his main assistant enter speeches and other communication into an early computer, stayed about a year and emerged a practicing Buddhist. “What a charming man. At the time he was fairly young. He has a translator and he asks questions: Where are you from? How did you get here? What do you do? He’s just fascinated,” she says.

“Mom was always very independent,” says son Eric. “She’d decide she wanted to do something, she’d just pick up stakes and do it.” In the early ’90s, that included a return trip to North Carolina, where she lived in a houseboat on the Cape Fear River listening to the fish jump and the alligators chomp until it was destroyed in a hurricane. The storm blew her back to Vancouver.

Then, in her early 60s, Ragan pulled up stakes again and headed back to New York. “I’d always wanted to live there. Who doesn’t? Art. Music. People. It’s possibly the greatest city in the world,” she says. She studied graphic design at NYU and lived in an apartment on the Upper West Side at 84th and Columbus. It was an easy walk to Central Park and the Natural History Museum. “My very favorite place to eat was the buffet brunch in the spectacular Peacock Alley at the Waldorf-Astoria hotel,” she says. “It was fairly expensive, but the food was excellent, and there was always a scattering of semi-celebrities having brunch along with us regular folk.” Then the rent controls came off and, as Ragan says, “Here I am.”

In his 1986 volume of poetry, A Walk into April, Sam Ragan has a poem entitled “Nancy.” It goes:

You talked about bluebirds

When you were three—

And the bright bluebird

Winging into the sunlight

Always seems a part of you.

There was that song,

“Nancy With the Laughing Face,”

Which brightened dark days of long ago,

And other sights and sounds

Flood the memories

Of someone very special.

It has been a wonderful journey,

And it’s the journey that counts,

Not the getting there.

Here at home the dogwood is in bloom,

And across the miles I am proud

That others share my pride in you—

The very special you.

It seems the gift of producing art in the miniature may be genetic. PS

Jim Moriarty is senior editor of PineStraw and can be reached at jjmpinestraw@gmail.com.