SIMPLE LIFE

Bravo, Ben Franklin

And may there be more questions and answers on the road ahead

By Jim Dodson

My wife, Wendy, and I are a true marriage of opposites. She’s your classic girl of summer, born on a balmy mid-July day, a gal who loves nothing more than a day at the beach, a cool glass of wine and long summer twilights.

I’m a son of winter, born on Groundhog Day in a snowy Nor’easter, who digs cold nights, a roaring fire and a knuckle of good bourbon.

With age, however, I’ve come to appreciate our statistically hottest month in ways that remind me of my happy childhood.

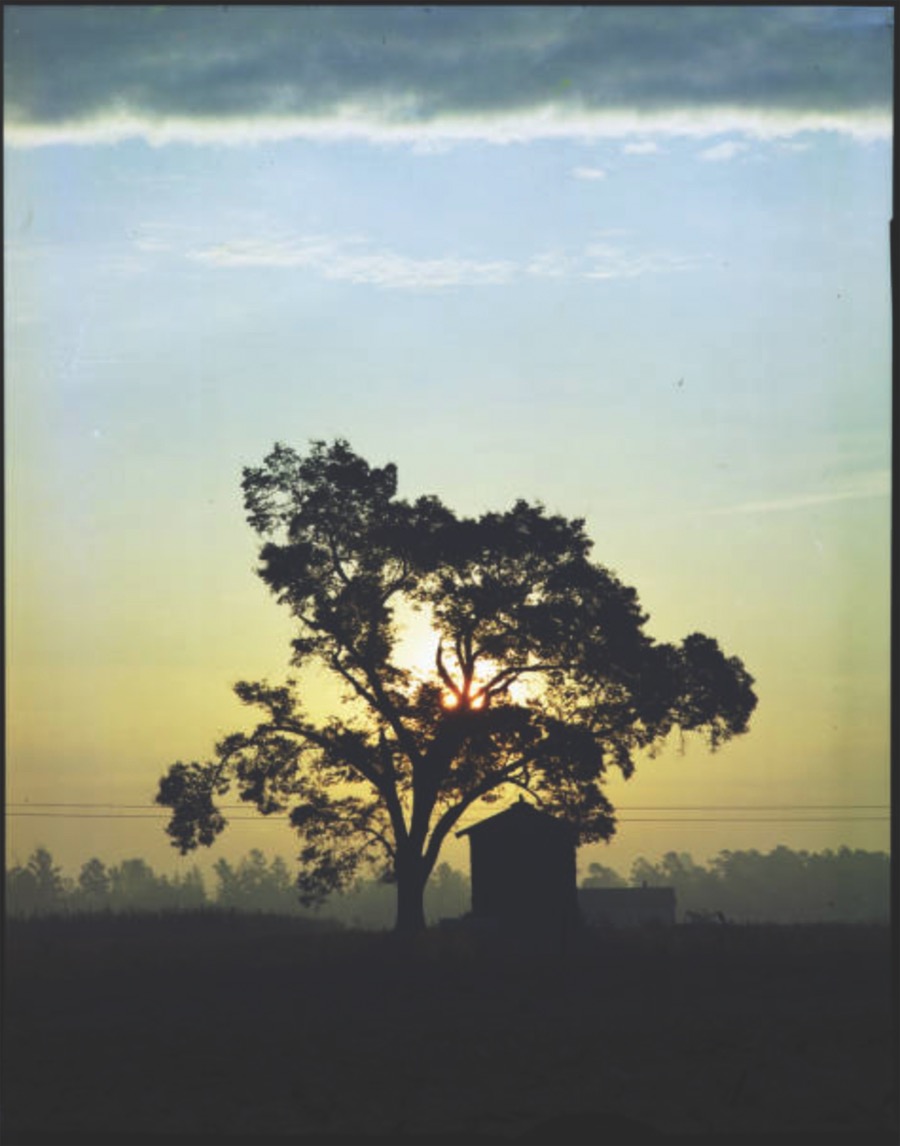

Growing up in the deep South during an era before widespread air conditioning, I have fine memories of enjoying the slow and steamy days of midsummer.

Like most American homes in the late ’50s and early ’60s, the houses where we lived during my dad’s newspaper odyssey across the deep South were cooled only by window fans and evening breezes. The first time I encountered air conditioning was in a small town on the edge of South Carolina’s Lowcountry, where only my father’s newspaper office and the Piggly Wiggly supermarket were air-conditioned.

Trips to the grocery store or his office were nice, but I had my own ways to beat the heat. I’d pedal my first bike around the neighborhood or crawl beneath our large wooden porch, where I’d conduct the Punic wars with my toy Roman soldiers in the cool, dark dirt.

On hot summer afternoons, I’d sit in a wobbly wicker chair on the screened porch, reading my first chapter books beneath a slow-turning ceiling fan, keeping a hopeful eye out for a passing thunderstorm, probably the reason I dig ferocious afternoon thunderstorms to this day.

July also brings the Fourth of July, our national Independence Day, which I unexpectedly gained a new appreciation for during my long journey down the Great Wagon Road over the past six years. The Colonial backcountry highway brought my Scottish, German and English ancestors (and probably yours) to the Southern frontier in the mid-18th century.

My fondest memory of celebrating the Fourth was sitting on a grassy fairway at the Florence Country Club, watching my first fireworks display. My mother brought along cupcakes decorated with red, white and blue icing.

That same week, Mr. Simmons, a cranky old fellow on our street, told my best friend, Debbie, and me that “only Yankees celebrate the Fourth of July because they won the War Between the States.”

My dad, a serious history buff, told me this was complete hogwash and began taking my older brother and me to hike the Revolutionary War battlefields of South Carolina at Camden, Kings Mountain and Cowpens, drawing us into the story of America’s fight for independence from Great Britain. When we moved to Greensboro in 1960, one of our first stops was the Guilford Courthouse National Military Park, where the pivotal battle of the Revolutionary War was fought.

My favorite Fourth of July celebration took place at Greensboro’s Bur-Mil Club in the mid-1960s. It was a lovely affair that featured races in the swimming pool and a par-3, 9-hole golf tournament for kids, followed by a huge company picnic in the dusk before a fireworks display.

That summer, I joined the club’s swim team and even briefly set a city record for 10-and-under in the backstroke, developing a daily routine that made beating midsummer heat a breeze. Every morning after swim practice, I played at least 27 holes under the blazing sun (bleaching my fair hair snow-white by summer’s end), grabbed a hot dog and Coke in the club snack bar for lunch, then headed back to the pool to cool off before my dad picked me up on his way home from work. Looking back, it was hard to beat that summertime routine.

Fast forward several decades, I was thinking about these pleasant faraway summers on the first day of my journey down the Great Wagon Road, beginning in Philadelphia. The city was still draped in the tricolors of Independence Day amid a record-breaking heat wave. After a morning hike around the historic district, I walked into the shady courtyard of the historic Christ Church, hoping to find some relief, but found, instead, Benjamin Franklin sitting on a bench.

I couldn’t believe my good luck. Rick Bravo was a dead ringer for Philly’s most famous citizen and said to be the most beloved of Philly’s Ben Franklin actor-interpreters.

He invited me to share the bench with him while he waited for his wife, Eleanor, to pick him up for a doctor’s appointment.

Over the next hour, Ben Franklin Bravo (as I nicknamed him) regaled me with several intimate insights about my favorite Founding Father, including how “America’s Original Man” shaped its democratic character and even had a hand in designing the nation’s first flag, sewn by Betsy Ross.

I thanked him for his stories and wondered if I might ask one final question.

He gave me a wry smile and a wink.

“God willing, not your last question nor my last answer,” he replied with perfect Franklin timing, casually mentioning that he was scheduled to undergo heart surgery within days.

I asked him what it was like channeling Benjamin Franklin.

Rick Bravo glanced off into the shadowed courtyard, where a mom and three small kids were cooling off with ice cream cones, chattering like magpies. My eyes followed his.

He grew visibly emotional.

“Let me tell you, it’s simply . . . wonderful. Next to my wife and children, being Ben Franklin is the most meaningful thing in my life.”

He told me how he met Eleanor many decades ago in the first of their many musical performances together, a major production of Oliver!

“Like America itself, we’ve weathered the ups-and-downs of life with lots of grace from the Almighty and a good sense of humor. As Ben Franklin himself observed, both are essential qualities for guiding a marriage or shaping a new country.”

Looking back, my hour with the man who was Ben Franklin proved the most memorable conversation of more than 100 interviews I conducted along the Great Wagon Road.

He even suggested that I drop by Betsy Ross’s shop over on Arch Street to buy a replica of the young nation’s first flag as a symbol of the birth of America.

Over the next five years, I carried this beautiful Ross flag, with its red-and-white stripes and circle of 13 stars, the only purchase I made during my entire 800-mile journey, down the road of my ancestors.

To celebrate publication of my Wagon Road adventure this month, my Betsy Ross flag will proudly hang in front of my house for the first time, a gesture of gratitude to the dozens of inspiring fellow Americans I met on my long journey of awakening.

It will also hang in memory of my dear friend, Ben Franklin Bravo, my first interview on the Great Wagon Road, who died in January 2022.

I understand that Eleanor sang “Where is Love?” to him from their first musical together as he passed away.