PROFILES JANUARY 2026

January 2026

Enjoy a trio of January book talks beginning at noon on Thursday, Jan. 8 when Jack Kelly discusses his book Tom Paine’s War: The Words That Rallied a Nation and the Founder for Our Time virtually with Kimberly Daniels Taws at The Country Bookshop, 140 N.W. Broad Street, Southern Pines. Then, at 6 p.m. on Wednesday, Jan. 14, Ford S. Worthy will talk about his book In Search of a Boy Named Chester, also at The Country Bookshop. Last, but certainly not least, Donna Everhart will engage in a discussion about her book Women of a Promiscuous Nature, in the Boyd House at the Weymouth Center for the Arts & Humanities, 555 E. Connecticut Ave., Southern Pines. For information and tickets for all three events go to www.ticketmesandhills.com.

Erikson Herz knew from the age of 12 that magic was his calling, but the journey is about more than just tricks and illusions — it’s about connecting with people through wonder and imagination. You can catch his act at BPAC’s Owens Auditorium, 3395 Airport Road, Pinehurst, at 7 p.m. on Friday, Jan. 30. For information and tickets go to www.ticketmesandhills.com.

OK, maybe it’s still winter, but the Sandhills Woman’s Exchange will warm things up when it reopens for the spring season beginning on Wednesday, Jan. 28. The gift shop hours are from 10 a.m. to 3 p.m., and the cabin café will be serve up lunch from 11 a.m. to 2 p.m. For information go to www.sandhillswe.org.

The North Carolina Symphony will perform A Little Night Music on Thursday, Jan 29, at 7:30 p.m., in BPAC’s Owens Auditorium, 3395 Airport Road, Pinehurst. The Stephen Sondheim musical, originally performed on Broadway in 1973, includes the popular song “Send in the Clowns,” written for Glynis Johns. For more information go to www.ticketmesandhills.com.

“Yesterday and Today: The Interactive Beatles Experience” returns to BPAC’s Owens Auditorium, 3395 Airport Road, Pinehurst, beginning at 7 p.m. on Friday, Jan. 16. The band, anchored by brothers Billy, Matthew and Ryan McGuigan, performs as themselves and leave the song choices completely up to the audience. The set list is created as the show happens, and the songs make up the narrative for the evening. Every show is different, every show proves that The Beatles’ music truly is the soundtrack to our lives. For tickets and information go to www.ticketmesandhills.com.

The always thought-provoking Ruth Paul Lecture Series continues with Dr. Deigo Bohórquez, an associate professor of medicine and neurobiology at Duke University, delivering a presentation on “The Gut-Brain Connection and Neuropods” on Tuesday, Jan. 20 at 7 p.m. in BPAC’s Owens Auditorium, 3395 Airport Road, Pinehurst. A pioneer and leader in the field of gut-brain biology, Bohórquez focuses on how the brain perceives what the gut feels, how food in the intestine is sensed by the body, and how a sensory signal from a nutrient is transformed into an electrical signal that alters behavior. In 2025, he was awarded the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers from President Joe Biden, the highest honor bestowed by the United States government on outstanding early-career scientists and engineers. For tickets and information go to www.ticketmesandhills.com.

Experience a world where film and music become one when The Carolina Philharmonic, under the direction of Maestro David Michael Wolff, performs the iconic Wizard of Oz soundtrack live-to-picture in two performances — at 3 p.m. and 7:30 p.m. — on Saturday, Jan. 24, in BPAC’s Owens Auditorium, 3395 Airport Road, Pinehurst. For further information go to www.carolinaphil.org. or call (910) 6897-0287.

Get swept up in a night of smooth rock at 7 p.m. on Friday, Jan. 23, when Dirty Logic, the Steely Dan tribute band known for its impeccable musicianship and faithful recreations of the Donald Fagen and Walter Becker jazzy grooves, lush harmonies and razor-sharp lyrics, takes the stage at the Sunrise Theater, 250 N.W. Broad St., Southern Pines. Tickets are as affordable as $39 to get through the door, up to $139 for the VIP, dinner, drinks and premier seating treatment. For more information and tickets go to www.sunrisetheater.com.

The Met has assembled a world-beating quartet of stars for the demanding principal roles in Vincenzo Bellini’s 1835 opera I Puritani on Saturday, Jan. 10, at 1 p.m. at the Sunrise Theater, 250 N.W. Broad St. Southern Pines. Soprano Lisette Oropesa and tenor Lawrence Brownlee are Elvira and Arturo, brought together by love and torn apart by the political rifts of the English Civil War. Baritone Artur Ruciński plays Riccardo, betrothed to Elvira against her will, and bass-baritone Christian Van Horn portrays Elvira’s sympathetic uncle, Giorgio. For info and tickets go to www.sunrisetheater.com.

By Jenna Biter

Photographs by John Gessner & Todd Pusser

“I’ve always been interested in birds,” Dr. Joseph H. Carter III says, as matter-of-fact as his graying hair and beard.

The ecologist looks out from a pair of rimless glasses. He’s reclined in a dark leather chair with a knee propped up on a dark wooden desk opposite a fireplace framed by white tiles painted with mallards and other birds. A stuffed-animal opossum stares down from a shelf. Volumes including Saving Species on Private Lands and Manual of the Vascular Flora of the Carolinas line the wall behind him. “I started my life list of birds when I was 13.”

A birder’s “life list” is precisely what you’d think. It’s a running total of all the species they’ve spotted and identified. Carter has tallied 300 and some. “It’s really not that many,” he says. Most of the birds on his list are local to North Carolina, the place where his interest took flight.

Amassing an eyepopping number — say, a thousand or more — hasn’t been Carter’s life mission. That was reserved for one species in particular, the red-cockaded woodpecker.

After earning a degree in biology from the University of North Carolina at Wilmington and graduate degrees from North Carolina State, Carter launched his environmental consulting firm, Dr. J.H. Carter III & Associates, in 1976, when he was 26 years old. His first contract was with the North Carolina Department of Transportation consulting on the four-laning of U.S. 421 north of Wilmington.

It was in the Sandhills, where he grew up, that Carter’s devotion to the once-endangered (now-threatened) red-cockaded woodpecker transformed into one of the largest, longest-running research studies of any one species. The Sandhills Ecological Institute, a nonprofit organization Carter founded in 1998, helps run the study and is located next to his consulting firm on Midland Road.

Carter spent his boyhood in Southern Pines distracted by the flash of feathers. “I’d be watching out the windows at school,” he says. “Every day I wrote down every bird I saw, even if it was a starling or whatever.”

After school let out, Carter continued his birdwatching exploits at home. He’d walk into the family house on the “Little Nine” — the Southern Pines Golf Club’s now fallow nine holes — and right back out with binoculars dangling from his neck, disappearing into the woods bubbling with creeks and swamps in the swaths of nature the golf course didn’t occupy.

“My first pair of binoculars were my dad’s. He was in the Navy in World War II and brought his nautical binoculars back. They were about this . . . ” Carter says, measuring a great distance between his hands, “and weighed about seven or eight pounds. I probably did permanent damage to my neck wearing those things.”

Carter began banding birds when he was out of school with mononucleosis. “I got a banding permit from the federal government and just dove in,” says Carter. In the ’60s, it wasn’t difficult to acquire a permit for yard banding. Today, a citizen scientist needs to be involved with a research project to tag birds.

Carter set up a system of feeders and super-fine “mist nets.” Attracted by the food, the birds would fly into the nets, safely and temporarily captive. Carter took measurements, weighed the birds, distinguished the sex if he could, banded them and turned them loose. “I banded everything that came to the feeders,” he says. “Every day it was sunup to sundown — band, band, band, band.”

That winter Carter tagged more than 300 evening grosbeaks, 400 pine siskins and 900 purple finches traveling from Canada in a winter finch invasion. After he recovered from his illness, his hobby remained. He zigzagged across the Sandhills banding with his birder-mentor, a woman named Mary Wintyen. After getting his driver’s license, his territory expanded: Drowning Creek, Little River, the local lakes.

“I was going to the lakes looking at the waterfowl,” Carter says. “Other kids were doing teenage stuff. I was out there crawling around in the woods, trying to find neat things. I kept up with snakes and salamanders and all that stuff.”

But neither snakes nor salamanders — not even waterfowl, northern finches or other birds — would weave through Carter’s life like the red-cockaded woodpecker, a species he saw for the first time in September 1963 near the 12th green of the golf club.

Red-cockadeds are smallish woodpeckers, slightly longer than a new No. 2 pencil from eraser to the blunt end. The birds are almost entirely black and white, but the males wear a cockade, a tuft of red feathers on each side of its head, that gives them their name. Native to forests across the southeastern United States, their homes of choice are old longleaf pines, where they’ll peck themselves cozy cavities in which to roost and nest.

“After they make a cavity, they dress up the tree, and the tree gets a reddish appearance. Then they peck what we call resin wells in the tree,” Carter explains. “Because the tree’s alive, it bleeds resin, and it eventually turns the tree white. We call them candlesticks in the forest.”

If the sap has dulled to a dirty, yellowish gray, the red-cockaded woodpeckers have vacated long ago. Carter remembers seeing abandoned cavities while crisscrossing Moore County with Wintyen. “You’d see them on the golf courses. You’d see them on the side of the road,” he says. Birds were still active but their numbers seemed to be declining, and Carter was curious.

“I’ve been interested in the red-cockaded woodpecker since I was 15. That was when the first paper I co-authored was published in our Carolina Bird Club journal, the Chat,” says Carter. He and Wintyen wrote the paper for the bulletin in 1965. They described the cavities they’d seen. Where they were. What they were like. Only one nest, possibly two, was active, and Carter didn’t know the cause of the species’ decline. At the time, it wasn’t clear.

“One thing just built on another and the woodpecker got listed as an endangered species,” he says.

Congress protected the bird under the Endangered Species Act of 1973. It was around then that Carter graduated from UNCW and applied to NC State for his master’s degree. Initially rejected, he decided to plead his case in person and pitch his plan for a sweeping study of a the red-cockaded woodpecker. “Survey everything, tag all the trees, catch all the birds, band all the birds, and then just track what was going on to answer some of these questions: Why are the birds decreasing? How many are there? All the basic demographic questions you need to answer,” Carter says, outlining the elephant-size task.

The secretary for the head of the Zoology Department was out, but Carter could see that the head of the department himself — Dr. David E. Davis — was in his office, seated just around the corner. “He spoke, like, six languages. He could lecture in Russian. He’s way, way up there,” Carter says. “I asked if I could talk to him and he said yes. I sat down. I didn’t know I was supposed to be scared of this guy. He listened, thanked me and sent me on my way.”

Later Carter got a phone call from an ornithologist he knew at NC State. So long as he could finish his master’s in a year, he was in. He began surveying Southern Pines, Pinehurst, McCain, the northern part of the Sandhills Game Lands and the western part of Fort Bragg. “It was getting a population estimate as well as being able to characterize the habitats they were in. You know, how old were the pines? How dense were the pines? How much of a midstory, scrub oaks and whatever?” Carter says. “So I did all that and then I graduated with my master’s degree.”

Banding the birds would have to wait until a sprawling study was funded. “We started banding in ’79,” Carter says. The grant secured money for red-cockaded woodpecker research across 400 square miles of the Sandhills. Originally the study lived at NC State. Eventually it moved to the Sandhills Ecological Institute, which was founded and runs — with the help of Carter — to study and preserve the longleaf pine ecosystem.

Through decades of bands-on-birds, boots-in-field research, scientists could finally answer the whys behind the red-cockadeds decline, a mystery that long ago grabbed the attention of a self-admitted obsessive teen. Loss of habitat was one factor: Across the centuries, tens of millions of acres of longleaf pine had been logged. Moreover, the policy of total fire suppression, adopted in the 20th century, was harming the biodiversity of the still-standing longleaf forests.

In retrospect, Carter knew something was off since the time he was just a curious kid exploring the woods with his dad’s old binoculars. There were no birds to see where turkey oaks and vines and shrubs crowded a pine forest’s midstory. But the aha moment didn’t come until years later when Carter surveyed Fort Bragg’s blast sites, where fire was the way of things. “All of a sudden, you can see to the horizon. There is no midstory,” Carter says, a touch of awe warming his gravelly voice.

There were woodpeckers all over the place. There were songbirds all over the place. To Carter, it was like discovering Atlantis. “You can’t have a longleaf pine forest without frequent, low-intensity fire, and its cycle and its nutrients.”

By the end of the ’80s, the red-cockaded woodpecker population had leveled, and there was potential for an uptick. Sometime around then, Dr. Jeffrey Walters, who had been involved with cockaded research since early days, secured funding to determine whether drilling artificial cavities into trees could boost the woodpecker’s numbers. As it turned out, it could, and Carter’s firm still drills artificial cavities today. You can even spot one of his company’s nests on Pinehurst’s No. 2 golf course.

Thanks to conservation efforts, the red-cockaded woodpecker was downgraded from federally endangered to threatened in October 2024. There are now an estimated 7,800 active clusters across 11 states in the Southeast — up from an all-time low of roughly 1,500 in the early ’70s when the Endangered Species Act became law.

As a threatened species, red-cockaded woodpeckers are still protected by the act. According to Carter, they are a “conservation-reliant species,” and their numbers will drop if management ceases.

Carter pushes back from his office desk. His cast of characters watch attentively from their fireplace tiles and shelf as he prepares to leave. “It’s a labor of — I hate to say labor of love, that sounds tacky as hell,” Carter says, “but it takes people who are willing to basically dedicate their lives to projects like this. Whether they’re studying elephants or bacteria or whatever, it takes folks like that. We’ve all benefited from each other and the sacrifices that we were willing to make to keep these things going.”

By Jim Dodson

I’m often asked by readers where I find my ideas to write about each month.

“It’s simple,” I reply. “Life.” Hence the title of this column.

It helps, however, that I also have what I call my “Green Books.” Not the historic Green Book that served as a guide to safe places for accommodations and food for traveling African Americans in the mid-1900s South.

Mine are something very personal: four leather journals, several with cracked bindings from age, that I began half a century ago. In their pages, I’ve recorded memorable quotes, funny observations and the wisdom of others who graciously provided food for the journey ahead.

Today, four such books anchor my writing desk and library shelves, crammed full of helpful words — some famous, others anonymous, comical, spiritual or plain common sense — a resource I turn to when life seems out of whack, or I simply need a shot of humor or optimism to face the moment.

A new year strikes me as the perfect time to share some of my all-time favorites.

“I fear the day that technology will surpass our human interaction. The world, as a result, will have a generation of idiots.” – Albert Einstein

OK. Had to put this one out first because I’m a confirmed Luddite who writes his books with an ink pen and can only function on a computer with proper adult supervision, meaning my wife, Wendy, a techno-whiz. Recently heard a “Super” AI “expert” warn that “living authors” will eventually be a thing of the past. That’s a world I don’t wish to live in.

“I knew when I met you an adventure was going to happen.” – from Winnie-the-Pooh by A.A. Milne

This gem hung with an illustration of Pooh, Piglet and Eeyore on my childhood bedroom wall. Stop and think for a moment about the amazing people you didn’t know until they unexpectedly, perhaps miraculously, stepped into your life — and a new adventure began.

“Tell me, what is it you plan to do with your wild and precious life?” – From “The Summer Day” by Mary Oliver

This timeless poetic question hung on a banner over my daughter Maggie’s beautiful autumn wedding three years ago at her childhood summer camp in Maine. It’s one we all must invariably answer, even late in life. Especially late in life.

“I went to the woods because I wished to live deliberately, to front only the essential facts of life, and see if I could not learn what it had to teach, and not, when I came to die, discover that I had not lived.” – from Walden: or Life in the Woods by Henry David Thoreau, poet, naturalist, Transcendental rock star.

I discovered — and memorized — this stanza in Miss Emily Dickenson’s English Lit class in 1970 (by the way, her real name). So moved by it, I vowed to someday retreat to the northern woods. Looking back, I think it partially explains why I built my house on a forested hilltop in Maine. That gold-and-green woodland enchanted my children and their papa, a would-be transcendentalist who has learned more from the solitude of the forest than in any city on Earth.

“There will be a time when you think everything is finished. That will be the beginning.” – Louis L’Amour, Western novelist

Useful advice for those of us anxious about the fate of American democracy.

“Solvitur ambulando.” Translation: It is solved by walking. –

St. Augustine

Amazing what a good walk around the block or hike through the woods can do to calm the mind, work out a solution or simply remind one how life’s ever-changing landscape can clear away the cobwebs.

“Stop looking at yourself and begin looking into yourself. Life is an inside job.”

Someone once said this to me, but I can’t remember who. I sometimes remind myself of this when I’m shaving in the morning and see myself in the mirror, often followed by a second observation: I thought getting older would take more time.

“If something is lost, quit searching for it. It will find its way back to you.”

Sage advice passed along from a longtime golf pal’s mama. I’ve found it works splendidly with misplaced car keys, eyeglasses, wallets, (most) golf balls and missing Christmas candy. Not so much with politics or old romances.

“The meal is the essential act of life. It is the habitual ceremony, the long record of marriage, the school for behavior, the prelude to love. Among all peoples and in all times, every significant event in life — be it wedding, triumph, or birth — is marked by a meal or the sharing of food and drink. The meal is the emblem of civilization.” – James and Kay Salter, from Life Is Meals: A Food Lover’s Book of Days

A well-loved book in our household, one every food lover should own, a gloriously entertaining volume chock full of quirky, fun and extraordinary gems about the origins and traditions of food, drink and fellowship at the table.

“In an age of speed, I began to think, nothing could be more invigorating than going slow. In an age of distraction, nothing could feel more luxurious than paying attention. And, in an age of constant motion, nothing is more urgent than sitting still.” – from The Art of Stillness: Adventures in Going Nowhere by Pico Iyer

This note from this wise little book pretty much summarizes my personal ambition for 2026 — to go slower, to pay closer attention, to sit still as often as possible.

“Modern American society is marked by a high degree of mobility, a decline in voluntary civic activities, and an emphasis on rights (i.e. what others owe me). The result is rootlessness and detachment from family and friends. Higher crime rates, chiefly among youth, show a strong statistical correlation with lack of self-control. And moral disputes are often marked by dogmatism, the inability or unwillingness to see the moral force behind another point of view. In response, the possibilities for improvement include (1) reinvigorating our civic associations, (2) developing and inculcating self-control, and (3) demanding higher levels of mutual respect and tolerance in the way we speak to and treat one another.” – from Civility & Community by Brian Schrag

May you all have a safe and much more civil New Year. I leave you with one of my favorite wisdoms from my books:

“Do not be afraid, for I am with you. From wherever you come, I will lead you home.” – Isaiah 43:5

By LuEllen Huntley

I am the new girl, a late enrollment. My parents and I are ushered into an expansive office with heavy drapes for an interview. They sit in the back on a plush couch, me up front in a straight-back chair across a hefty desk from the assistant headmistress, a smallish woman with thick oval glasses. She begins, “What have you read, Miss Huntley?”

I stare at her owlish face and freeze, incapable of telling her about our smalltown library a half block from my house. Ever since fourth grade I’d been allowed to walk there on my own and stay as long as I liked. The two librarians, Ms. Shep and her sister, allowed me access to all the rooms, even the attic that housed the Civil War archive, where they let me wander among the armed and uniformed manikins. Other days I pore over articles and discover Seventeen in the magazine alcove. Somehow I pass the interview. I tell my parents goodbye.

Most of the dorm rooms are doubles but, because I’m late, I’m assigned the single the other girls call “the pink ballerina room.” It’s a small room down a cornered hallway with an exterior window ledge almost large enough to crawl onto. I’m happy to have ballerinas dancing on the walls in pink tutus and toe shoes, reminding me of the program in third grade when I wore a ballet costume borrowed from a girlfriend. In the short tulle skirt, a sequined top and matching tiara, I played a wood fairy and learned a poem by heart. My mother pin-curled my hair the night before the performance, and I got to wear lipstick.

I play my music in the ballerina room, a collection of 45’s that includes Motown, The Doors, Johnny Rivers, The Beatles, James Taylor, Bread, The Guess Who and Carole King. Some of the other girls ask to borrow them. Weeks after moving in, one classmate in particular keeps dropping by. She’s the first person I know who wears round John Lennon glasses, setting off naturally curly hair, a sly grin and quirky laugh. I find out she’s a cartoon artist.

She starts chatting about her roommate, making it sound like I’m missing out. She says if I want a roommate, she has the best; and I can trade places with her, move to a double on a main hall. This way, she promises me, I’d have a roommate. I won’t be alone anymore. I fall for it and we swap, privacy for friendship. But the thought of the pink ballerina room never fully goes away. Like time alone in the town library, I enjoy solitude, the space to think. The girl with the John Lennon glasses finagled this gift for herself.

But I do like having a fun-loving roommate. After dinner we hold “dance-outs” in our room to my 45’s. It becomes the place to be, the place where 16-year-old ballerinas truly come to life, in the bargain of a lifetime. And I say this now because the new girl then did not know when she landed the private room tucked down the small hallway, off to itself, it was just the sort of place that fit the person she would become. The way of the universe was to give her a smalltown library and a few weeks in the pink ballerina room as a taste of independence. Each left its imprint.

The Infamous Gilberts, by Angela Tomaski

Thornwalk, a once-stately English manor, is on the brink of transformation. Its keys are being handed over to a luxury hotelier who will undertake a complete renovation but, in doing so, what will they erase? Through the keen eyes of an enigmatic neighbor, the reader is taken on a guided tour into rooms filled with secrets and memories, each revealing the story of the five Gilbert siblings. Spanning the eve of World War II to the early 2000s, this contemporary gothic novel weaves a rich tapestry of English country life. As the story unfolds, the reader is drawn into a world where the echoes of an Edwardian idyll clash with the harsh realities of war, neglect and changing times. The Gilberts’ tale is one of great loves, lofty ambitions and profound loss.

Meet the Newmans, by Jennifer Niven

For two decades, Del and Dinah Newman and their sons, Guy and Shep, have ruled television as America’s “Favorite Family.” Millions of viewers tune in every week to watch them play flawless, black-and-white versions of themselves. But now it’s 1964, and the Newmans’ idealized apple-pie perfection suddenly feels woefully out of touch. Ratings are in free fall, as are the Newmans themselves. Del is keeping an explosive secret from his wife, and Dinah is slowly going numb, literally. Steady, stable Guy is hiding the truth about his love life, and the charmed luck of rock ’n’ roll idol Shep may have finally run out. When Del is in a mysterious car accident, Dinah decides to take matters into her own hands. She hires Juliet Dunne, an outspoken, impassioned young reporter, to help her write the final episode. But Dinah and Juliet have wildly different perspectives about what it means to be a woman, and a family, in 1964. Can the Newmans hold it together to change television history or will they be canceled before they ever have the chance?

The Typewriter and the Guillotine: An American Journalist, a German Serial Killer, and Paris on the Eve of WWII,

by Mark Braude

In 1925, Indianapolis-born Janet Flanner took an assignment to write a regular “Letter from Paris” for a lighthearted humor magazine called The New Yorker. She’d come to Paris with dreams of writing about “Beauty with a Capital B.” Her employer, self-consciously apolitical, sought only breezy reports on French art and culture. But as she woke to the frightening signs of rising extremism, economic turmoil and widespread discontent in Europe, Flanner ignored her editor’s directives and reinvented herself, her assignment and The New Yorker in the process. While working tirelessly to alert American readers to the dangers of the Third Reich, Flanner became gripped by the disturbing crimes of a man who embodied all of the darkness she was being forced to confront: Eugen Weidmann, a German conman and murderer, and the last man to be publicly executed in France mere weeks before the outbreak of WWII. Flanner covered his crimes, capture and highly politicized trial, seeing the case as a metaphor for understanding the dangers to come.

Opera Wars: Inside the World of Opera and the Battles for Its Future, by Caitlin Vincent

Drawing on interviews with dozens of opera insiders — as well as her own experience as an award-winning librettist, trained vocalist, opera company director, and arts commentator — Vincent exposes opera’s internal debates, never shrinking from depicting the industry’s top-to-bottom messiness and its stubborn resistance to change. Yet, like a lover who can’t quite break away, she always comes back to her veneration for the art form and stirringly evokes those moments on stage that can be counted on to make ardent fans of the most skeptical.

The Amazing Generation: Your Guide to Fun and Freedom in a Screen-Filled World, by Jonathan Haidt and Catherine Price

This engaging guide is packed with surprising facts, a graphic novel, interactive challenges, secrets that tech leaders don’t want kids to know, and real-life anecdotes from young adults who regret getting smartphones at a young age and want to help the next generation avoid making the same mistakes. It’s a bold, optimistic, and practical guide to growing into your most authentic, confident, and adventurous self. (Ages 9 – 12.)

The Wildest Thing, by Emily Winfield Martin

What would you do if you let the wild in? With gorgeous illustrations, this book is the ideal addition to any bedtime reading routine or read aloud. The Wildest Thing beautifully expresses a timeless message about little ones unleashing their inner “wild” and encouraging their budding imagination and unique individuality. (Ages 3 – 7.)

Rock and Roll, by Ruby Amy Thompson

A laugh-out-loud story of friendship that reminds readers that first impressions can be deceptive. Rock is strong, and Roll is soft. Rock hates attention. Roll loves it. But they are both team players; they are able to handle pressure; and they LOVE to get dressed up. Maybe they’re not so different after all! This sweet story reminds readers that first impressions can be deceptive. (Ages 3 – 7.)

By Warren L. Bingham

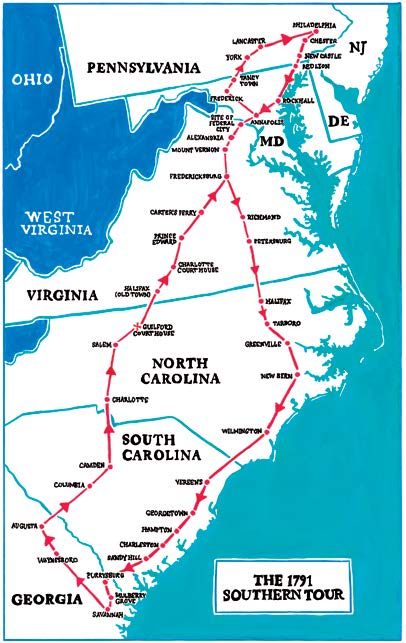

As the hero of the American Revolution and a man of action, George Washington knew his presence mattered. Shortly after becoming president, he planned to visit all 13 states, “to see and be seen” while promoting the new Constitution and the federal government.

By 1791 Washington had made trips to the Middle and Northern states. That spring he would conduct the Southern Tour, traveling to Virginia, the Carolinas and Georgia. Except for brief visits in the 1760s as a landowner in North Carolina’s Great Dismal Swamp, Washington had never been south of Yorktown.

The Southern Tour was the most challenging of Washington’s journeys. The president would leave from the nation’s temporary capital, Philadelphia, and be away over three months to reach the farthest points in South Carolina and Georgia. Roads were bad. Crossing water was often an adventure. Inns were few and far between, and the standard unreliable. Horses required proper provisions. Bad weather, clouds of dust and even highway robbery loomed as threats — though one supposes the prospect of holding up Washington and his traveling party would have required an extraordinarily witless band of criminals.

Nonetheless, the 59-year-old Washington and eight traveling companions embarked on the Southern Tour on the first day of spring of 1791. Cabinet members Thomas Jefferson and Henry Knox escorted the entourage from Philadelphia to Delaware. Washington left a detailed itinerary with Vice President Adams and his cabinet members if they sought to get mail or messages to him.

Washington was paid a whopper of a salary as the first president, $25,000, but he covered his own expenses for his residence, office and presidential duties, including travel. He paid his household staff and secretaries from his earnings.

The presidential entourage included seven servants from his Philadelphia home, two of them enslaved men on loan from Mount Vernon. William Jackson, a longtime secretary of Washington’s, served as top aide on the trip. Jackson, an officer during the Revolution and a Charlestonian, was young and single, making him ideal to take along on the journey. The trip was considered too arduous for a lady, so first lady Martha Washington remained at home, even though she was a veteran of some wartime camps.

Transportation included the president’s own cream-colored coach and four, a baggage wagon pulled by two horses, and a few extra saddle horses. Washington’s personal mount, Prescott, a tall white parade horse, made the trip. Quite aware of looking presidential, Washington, who stood 6 feet, 2 inches tall, made a dashing impression riding high in Prescott’s saddle. Folklore suggests that a greyhound named Cornwallis accompanied the travelers, but alas, the presence of the hound is likely a myth.

Washington was a planner, and he immersed himself in the journey’s details. He consulted with his secretaries and gentlemen travelers to understand the roads and inns of the South. The president decided to go south along the fall line and the Coastal Plain and to make the return north through the Piedmont, the higher land between the Lowcountry and the mountains. He charted a route that gave him a good feel for the region, though he specifically wanted to visit Charleston, South Carolina, then the fourth-largest city in the country and a place of influence and affluence. Georgia’s two notable places were Savannah and Augusta, so he was going no farther south than those towns. Atlanta didn’t yet exist.

The trip from Philadelphia to North Carolina was a memorable one. The travelers endured near-calamities while crossing both the Chesapeake Bay near Annapolis and the Occoquan River in Virginia. Stops in Fredericksburg, Richmond and Petersburg went well, however, and represented Washington’s typical reception. The president was feted by dinners, dances and cannon salutes. Upon his arrival, parades ensued, church bells rang and choirs sang. Eighteenth century drinking was impressive and many toasts were offered — usually 13 (one for each state, of course) with a few more thrown in for good measure.

Hosts dressed up in their finest clothes, and women wore sashes adorned with words of tribute such as “Long Live Washington!” Some towns were lit up with torches, candles and bonfires, a prospect that would have alarmed any self-respecting fire marshal, had such public safety civil servants existed then.

Elected officials, Masons, ministers and veterans of the Revolution were received by the president. He sometimes attended church services and occasionally had the luxury of riding Prescott around town simply to see who he might see.

Traveling between the larger towns wasn’t easy. Local militias often escorted the president, stirring up a choking dust. The inns along the road were often “indifferent,” a term Washington used to politely describe barely acceptable accommodations for man and beast.

On Saturday, April 16, 1791, nearly four weeks after leaving Philadelphia, wind, rain and lightning filled the air as the president and his party made their way into North Carolina. Washington wrote:

The uncomfortableness of it, for Men and Horses, would have induced me to put up; but the only inn short of Hallifax having no stables in wch. the horses could be comfortable & no rooms or beds which appeared tolerable, & every thing else having a dirty appearance, I was compelled to keep on to Hallifax.

At the end of this stormy day, Washington crossed the Roanoke River, arriving in Halifax around six in the evening for his first true taste of North Carolina. Any visit Washington had previously made to the Great Dismal Swamp hardly counts — it’s like saying you’ve been to Dallas after changing planes at DFW.

It’s not certain where Washington lodged during his two-night visit to Halifax, but it was probably Eagle Tavern. As much as practicable, he refused private lodging during his presidential journeys, either paying his way or agreeing to stay in community-provided accommodation. At times during the Southern Tour, however, there simply wasn’t a suitable public place available. Of course, the horses had to be properly cared for and fed — and some public houses weren’t even reliable enough for that.

Halifax was home to several notable North Carolinians, among them, Congressman John Baptist Ashe, future Gov. William R. Davie, and Willie Jones, who had led North Carolina’s opposition to the Constitution and was no fan of the federal government. Indeed, Jones suggested he would receive Washington as a great man — but not as president of the United States.

Though Washington was greeted politely and treated respectably in Halifax, there’s no doubt that the presence of Jones tempered the enthusiasm. After all, Washington was in town for only two days, but the locals had to live with Jones long after the president was gone.

Samuel Johnston, an Edenton lawyer and the squire of Hayes Plantation, wrote in a late-May letter to James Iredell that “the reception of the president in Halifax was not such that we could wish tho in every other part of the country he was treated with proper attention.” In 2011 — with the specter of Jones long dead and buried — Halifax commemorated the Southern Tour on Historic Halifax Day.

When he reached Tarboro, Washington was impressed by the bridge — a rarity in 1791 — over the Tar River. Apparently, the number of cannon in Tarboro was in agreement with the number of bridges. Washington wrote, “We were received at this place by as good a salute as could be given with one piece of artillery.” Reading Blount, a veteran of the Revolution and a member of the state’s prominent Blount family, led the president’s entertainment.

Washington made his way from Tarboro to Greenville along roads that no longer exist, but his route probably tracked near today’s Route 33. In Greenville, the president, ever a farmer, was pleased to learn about local crops, including tobacco, and was intrigued by tar-making and its commercial value. Nonetheless, Washington wrote that Greenville was a trifling place. Greenvillians shouldn’t fret; the president would say the same thing about Charlotte.

After a night near present-day Ayden, during which Washington worried about the horses going uncovered without stables, the travelers passed near Fort Barnwell en route to New Bern. Likely edging out Wilmington as the largest town in North Carolina in 1791, New Bern turned out smartly for Washington. Mounted militia and town leaders met the president’s party several miles outside town to act as escort. The city provided a new but never occupied home for the president’s stay, the John Wright Stanly home, which still stands and is part of today’s Tryon Palace complex.

On his second night in town, Washington was entertained at a gala at Tryon Palace, and his dance card was full. In recent years, a yellow gown worn that evening by Mrs. Ferebe Guion was shown and evaluated on PBS’ “Antiques Roadshow.” The dress, value unknown, remains in the hands of Guion descendants.

In an age of slow and unreliable mail, Isaac Guion, Ferebe’s husband, took advantage of the presidential traveling party and their Southern passage to send a letter to a friend in Georgia via the president. Imagine the conversation. “Uh, Mr. President, as long as you’re going . . .” I suspect William Jackson, the secretary, handled it, but indeed the letter was carried to Georgia and ultimately delivered.

In the 1940s, A.B. Andrews Jr., a Raleigh lawyer and history buff, came across the letter, acquired it, and presented it to the town of New Bern. It’s kept in the archives in the Kellenberger Room, a wonderful collection of local, regional and state history and genealogy at the New Bern-Craven County Public Library. With all these ties to the Southern Tour, New Bern held major commemorations of Washington’s visit in 1891 and again in 2015.

A cannon salute roared as Washington left New Bern, and the presidential party traveled through Jones County, a namesake of Halifax’s Willie Jones. Longtime Pollocksville mayor and avocational historian Jay Bender wonders why Washington stayed so far inland as he went south from New Bern. The old King’s Highway, the post road that went from Boston to Charleston, came through New Bern and tracked more directly to Wilmington. The reason might have been lodging and services for man and horse, since Shine’s Tavern in Jones County, where Washington put up for the night, enjoyed a good reputation.

The travelers arrived at the coast, a few miles from Topsail Beach, on Saturday, April 23. By late afternoon they linked up with present-day Holly Ridge and the King’s Highway, today’s U.S. 17. Washington lodged at Sage’s Inn, one of the establishments he labeled as “indifferent,” though another traveler of the era described the proprietor, Robert Sage, as a “fine jolly Englishman.”

On Easter Sunday, the presidential party followed the King’s Highway toward Wilmington, resting in Hampstead. Some claim that Hampstead takes its name from Washington requesting ham instead of oysters for his breakfast that morning. There is a large live oak hard by U.S. 17 in Hampstead that supposedly is where the travelers rested. A local DAR chapter has kept the tree marked as the Washington Oak for a century or more.

At some point on Easter, Washington wrote a long diary entry in which he observed that the land between New Bern and Wilmington was the most barren country he ever beheld. The travelers had gone through a vast longleaf pine savanna, and Washington had never seen anything like it.

While Washington attended church services several times during the Southern Tour, he made no mention of Easter or attending a service in Wilmington. The Port City’s streets were lined with people to catch sight of America’s hero as Washington was led to his lodgings, a home on Front Street provided by the widow Quince, who gave up her home for the president while she stayed with family elsewhere in town.

Historian Chris Fonvielle, an emeritus professor at UNC Wilmington, says that Wilmington entertained Washington lavishly, and that it was evident that the president “enjoyed the attention from the ladies and drinking with the gentlemen.” Indeed, Washington’s diary indicates there were 62 ladies at the ball. Fonvielle confirms that Washington spent time at two taverns, Dorsey’s and Jocelyn’s. Tavern keeper Lawrence Dorsey famously told the president, “Don’t drink the water!”

Washington’s party continued south on Tuesday the 26th with several stops in Brunswick County. The president met with Benjamin Smith of Belvidere Plantation. Smith was prominent in many ways, a future governor and large landholder, and an officer under Washington’s watch at some point during the Revolution. Southport was originally named Smithville in Benjamin Smith’s honor as he donated the land for the town. Bald Head Island is still known to some as Smith Island, as its original owner was Benjamin Smith’s grandfather, Thomas Smith.

After a night at Russ’ Tavern, about 25 miles south of Wilmington, the travelers stopped at William Gause’s Tavern on the mainland side of what’s now Ocean Isle Beach. Local lore says that the group took breakfast there and went for a swim in the swash, waters that are now the Intracoastal Waterway. The story goes that the president hung his clothes to dry in a large live oak by Gause’s that still stands. Washington crossed into South Carolina early on the afternoon of April 27.

The president continued his travels through South Carolina and Georgia and returned north to North Carolina in late May with stops in Charlotte, present-day Concord, Salisbury, Old Salem and Guilford Courthouse. Washington moved fast on the northbound return. His departures were often at four and five a.m. after one-night stays. In Charlotte, the president was hosted by Thomas Polk, a former officer during the Revolution and the great-uncle of future president James K. Polk. Washington lodged at Cook’s Inn on the corner of Trade and Church Streets where reportedly he left behind his powder box — not gunpowder but powder for body and hair.

Washington enjoyed two nights in Old Salem. Though he planned to spend only one evening, the president agreed to spend another day upon learning that North Carolina governor Alexander Martin was on the way to meet him but wouldn’t arrive until the next day. The president was impressed by the Moravians’ “small but neat village” and their ingenuity, having devised a clever water distribution system.

Before the creation of Greensboro, the county seat of Guilford was Guilford Courthouse, the site of a significant battle of the Revolution just 10 years earlier. Throughout the Southern Tour, Washington enjoyed seeing the battlegrounds that he had long read about. This was no different. “I examined the ground on which the action between Generals Greene and Lord Cornwallis commenced,” wrote Washington.

His last stop in North Carolina was an overnight stay with Dudley Gatewood in Caswell County, just south of the Virginia line. Gatewood’s home was disassembled and moved to Hillsborough during the 1970s, where it was reassembled and served many years as a Mexican restaurant. Sadly, the home gradually fell into disrepair and was torn down in 2024.

The travelers continued north through Virginia, spending time at Mount Vernon and in Georgetown, Maryland, where the president met with area residents to make plans and arrangements to create the new federal capital on the Potomac. Washington celebrated July 4 in Lancaster, Pennsylvania, and the travelers arrived back in Philadelphia on July 6. Church bells pealed to honor his return. The odometer had turned nearly 1,900 miles and Washington noted that he had gained flesh while the horses had lost it.

America’s first president never again went south of Virginia, but his visit to North Carolina and the South in 1791 was a great success. The Stanly House in New Bern and Salem Tavern in Old Salem are the only extant places where the first president slept, but the legacy is alive and well. The journey was a remarkable physical feat, and politically, Washington’s presence among the citizens and leaders of the nascent United States created considerable good will and acceptance of the new federal government, helping to cement the legacy of 1776.

By Jim Moriarty

I confess to being a New Year’s Scrooge. To those of us whose passing will be marked by the screwing of a brass plate into a particular spot at the end of a bar, the shenanigans and tomfoolery of the evening was commonly dismissed as “amateur night.” There is, however, one New Year’s Eve that I’ll not soon forget, and I’ve forgotten a lot of them.

I was married in an honest-to-God church during the fertile days between Christmas and New Year’s. Contrary to rumors, widespread at the time, this was not entirely done because the Methodist church was already decorated to the rafters, thus sparing the happy couple, i.e., me, any expense sprucing the joint up. Not entirely, that is.

Once all the stammering (me again) and vowing was over and done with, the War Department and I lit off on our honeymoon adventure like the giddy misfits we were. We actually had not intended on having a honeymoon. The ceremony fell smack in the middle of the Arab oil embargo. Lines at the gas pump resembled particularly slow-moving queues for particularly boring Disney rides, and the national posted speed limit might just as well have featured a drawing of a slug as the number 55.

My mother, however, had seen an advertisement for a steeply discounted weekend at a posh Indiana resort hotel. She tore it out of the newspaper and booked it for us as a wedding present. We were off to French Lick — the honeymoon destination that launched a thousand jokes. It should be pointed out that French Lick’s most famous citizen, Larry Bird, was a teenager at the time.

We were driving in the first automobile I ever owned outright, a severely oxidized white Volkswagen Beetle that may well have rolled off the production line the same year Khrushchev threw up the Berlin wall. As was typical of the model in those days, nothing functioned quite the way it was supposed to. The heater worked, for example, but only in the summer. It was definitely not summer.

When we pulled up to the grand hotel in our coach (rust bucket), we were met by a sharply dressed valet attendant. To my everlasting regret, it was years too soon to be able to quote Eddie Murphy from Beverly Hills Cop. If ever there was an opportunity to utter the line “Can you put this in a good spot ’cause all of this shit happened the last time I parked here,” this was it.

Our glorious weekend began with bowling in the hotel’s basement and finished in a New Year’s Eve celebration that, much to the War Department’s indifference, revolved almost entirely around the Sugar Bowl, which was the national championship game between undefeated and No. 1-ranked Alabama and unbeaten and No. 3-ranked Notre Dame, the university that was a mile or two north on Eddy Street from our apartment. We had found ourselves in South Bend that fall because she was a highly employable teacher and I was a decidedly unemployable English major and a kept man — which, come to think of it, hasn’t changed all that much in the last 52 years.

Be that as it may, that particular New Year’s Eve was not so much memorable because on a third and 10 from their own 1-yard line, Notre Dame quarterback Tom Clements hit back-up tight end Robin Weber for a 35-yard gain that allowed the Irish to run out the clock and win an 11th national championship. No, no. It was memorable because the War Department had developed an abscessed tooth, and while I had one eye on Ara Parseghian and Bear Bryant, the other eye could only sit there and watch as her face and jaw swelled like a Jiffy Pop aluminum balloon. Oh, my God, I thought, her father is going to kill me when he sees her.

The next morning, New Year’s Day, we drove home in a snowstorm as the War Department, cradling her throbbing jaw in a gloved hand, stuffed dirty socks into the heating vents to stem the polar vortex blasting through them, whilst riding with her feet propped against the dash because of the two inches of watery slush that had been strained through the Swiss cheese wheel well behind the right front tire.

So, yes, I’m no fan of the ghost of New Year’s past.

Story and Photograph by Rose Shewey

If January feels dull and bleak, you’re not tackling it right. I’ll grant you this — the lack of snow around here, which could turn a gray landscape into a twinkling fairy tale, isn’t helping. Nonetheless, there is much beauty to be found and discovered around us, inside and out.

A drop in temperature offers us a unique chance to embrace the season’s quiet rhythm. It’s a good time of year to take stock, look inward, and find stillness. Even in the dead of winter — snow or no snow — January shines bright because the kitchen takes center stage for many of us and cooking with local winter crops is a celebration in itself.

Root vegetables have historically been a staple of a cold weather diet. Parsnips in particular have great timing: They are peaking around the holidays and last into the winter months. As an added bonus, parsnips get better with the cold. When a frosty night hits the root, the plant converts starch into simple sugars, like a natural antifreeze. The side effect is a noticeable boost in sweetness.

Also known as “white carrots,” parsnips lend a deep, earthy-sweet foundation to any soup. Achieving harmony is everything, though: the bright acidity of the wine, the sharp tang of Stilton, and the saltiness of pancetta all fuse to create a balanced flavor profile in this wintry soup.

Wintry Parsnip and Pear Soup with

Pancetta and Stilton

(Serves 4)

Ingredients

1 pound parsnips (about 2 large), peeled and cut into big chunks

2 pears, such as Bartlett or Bosc, cored and sliced into wedges

1 onion, sliced

1 tablespoon fresh thyme leaves

3 tablespoons olive oil

8 ounces pancetta, chopped

1 celery stalk, sliced

1/2 leek spear, halved lengthways and thinly sliced

2-3 garlic cloves, crushed

3/4 cup white wine

4-5 cups chicken or vegetable broth

2 bay leaves

1/2 cup heavy cream (optional)

Salt and pepper, to taste

Crumbled Stilton cheese, for serving

Directions

Preheat oven to 350 F. In a large bowl, toss parsnips, pears, onion and thyme with the olive oil and spread out in a roasting pan. Sprinkle with salt and pepper, cover with a lid or foil and bake for about 30 minutes. Remove lid or foil, add veggies and pears, then continue roasting for an additional 30 minutes. Heat a large pot over medium heat and cook pancetta for about 5 minutes. Drain off excess fat, if needed. Add celery and leek and cook for 2-3 minutes, then add garlic and cook for another 2-3 minutes, stirring frequently. Pour in wine and cook until the liquid is reduced by about half. Add 4 cups broth and roasted veggies together with the bay leaves. Allow the soup to simmer for 20-25 minutes — add more broth if liquid cooks down too much. Remove bay leaves and blend or pulse in batches. Add the soup back to the pot and stir in cream, if desired. Taste soup and adjust seasoning. Serve with crumbled Stilton or any other soup toppings you enjoy.

By Stephen E. Smith

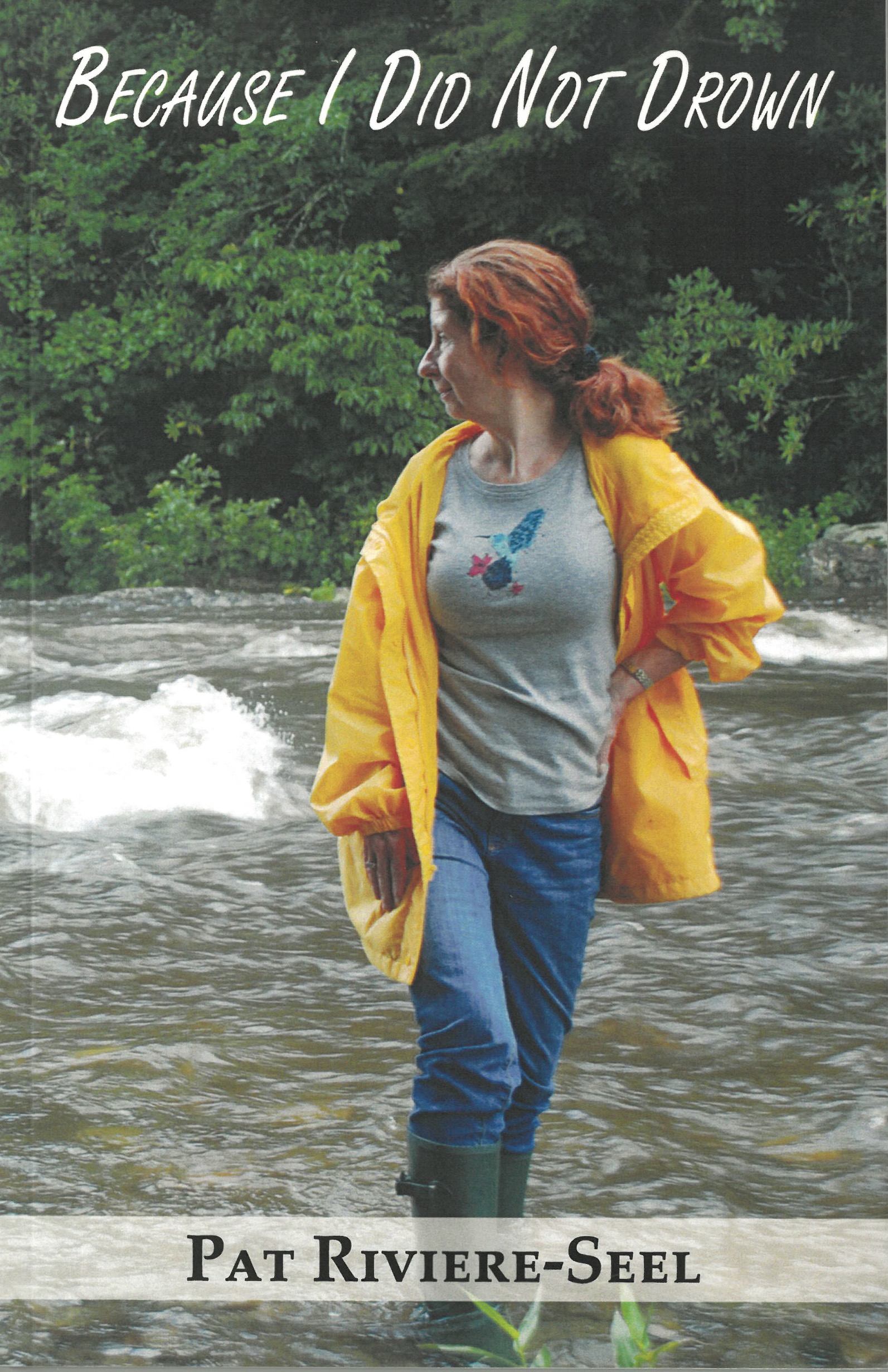

It happens to every writer. The moment comes, sometimes sooner than later, when it’s clear that he or she won’t live long enough to write every story that needs telling. The unwritten stories can be offered as spoken anecdotes, which, of course, vaporize the moment they’re uttered, so getting the stories down in print becomes a source of energy and inspiration. Pat Riviere-Seel’s collection, Because I Did Not Drown, derives its urgency from her desire to have the stories remembered — and to be remembered herself. “How long will the work of art last? Who will remember the artist . . . ?” she writes in her essay, “Unknown Artist.”

Reviere-Seel is the author of four poetry books, most notably the well-received The Serial Killer’s Daughter, which was published in 2009 by Charlotte-based Main Street Rag Press. Because I Did Not Drown explores both the exceptional and mundane — “kitchen talk,” the need for perseverance, the joy of pets (in this case cats), a stray fig plant growing by the back stoop, gun control, the loss of old friends, food lovingly prepared, an enthusiasm for jogging, “disenfranchised grief,” extraterrestrials, etc. Each prose chapter is written in straightforward journalistic prose and intended to convey helpful insights into contemporary life.

She begins her collection by recounting her personal experience with the COVID shutdown. She ends the book by detailing the ill effects of the pandemic’s aftermath, topics few writers have tackled (Sean Dempsey’s A Sad Collection of Short Stories, Cheap Parables, Amusing Anecdotes, & Covid-Inspired Bad Poetry is an amusing exception). This reluctance to write about the COVID experience can be attributed to what readers and writers might perceive as proximity aversion: the shock of COVID is still too much with us, and we’ve yet to sort out its spiritual and political implications. Reviere-Seel takes up the subject head-on: “But as the pandemic stretched into a second year, I became more frustrated, angry, and cranky. I missed my poetry group. I missed my friends. . . . We stayed home. We wore masks. We stayed six feet apart. We were grateful to be alive. . . . What had begun as a public health issue became a political issue. The usual anti-vaccine talk mingled with the talk of ‘the government can’t tell me what to do.’” Her concluding essay, “After the Pandemic,” suggests that kindness is the only possible remedy for a virus that continues to mutate: “Be kind. Most of us did not want to infect our family, our friends, our neighbors, or the checkout clerk at the grocery store who showed up for work every day. Genuine kindness is a balm, a gift, a grace.”

In her chapter “Talking About It,” she is straightforward about her struggles with breast cancer. “I didn’t talk about my experience with breast cancer,” she writes, but the death of an aunt who ignored a lump in her breast inspired her to share her experience. “Early detection and medical advances in treatment have meant that breast cancer is no longer the death sentence so many feared fifty years ago.” Her interaction with the medical community will be of particular interest. When she was denied an immediate needle biopsy, she reacted appropriately. “Nice was not working so I threw a fit, a nice-woman-goes-feral southern ‘hissy fit.’ A redhead-gone-rogue tantrum . . . I was paying for a service, medical care, and I wanted — no, demanded — a say in when and how that service was delivered.” Her story is a paradigm for all women and men who find themselves caught up in our often lethargic and convoluted medical system.

The course of her disease followed a predictable path, but she made the necessary decisions to preserve her life. The description of her battle with breast cancer is timely, honest, reassuring and possibly lifesaving.

Following each of the prose passages, a poem explicates or explores the theme of the preceding chapter. The poems are well written and could stand on their own as a chapbook. “After the Diagnosis,” for example, follows the chapter on breast cancer:

There are nights — more

than you ever thought you could endure —

when sleep will not come

your thoughts — no, not thoughts —

the deep well of unknowing appears

endless. You try summoning

visions of sunrise, a shoreline, bare feet

running across packed sand. But morning

fog covers this foreign landscape.

Everything you knew for sure yesterday

washed away with the tide, predictable

too the magical thinking, maybe. Abandon

the dock, row your way into the nightmare, further

out is the only way back.

The use of verse to add emotional impact to the short personal essays may strike some readers as unnecessary. At the very least, the transition from journalistic prose to poetry is complex, requiring a complete shift in sensibility and focus. Nevertheless, she forces readers to grapple with many of our most vexing problems.

We use cookies to improve your experience on our site. By using our site, you consent to cookies.

Manage your cookie preferences below:

Essential cookies enable basic functions and are necessary for the proper function of the website.

Statistics cookies collect information anonymously. This information helps us understand how visitors use our website.

Google Analytics is a powerful tool that tracks and analyzes website traffic for informed marketing decisions.

Service URL: policies.google.com (opens in a new window)

SourceBuster is used by WooCommerce for order attribution based on user source.