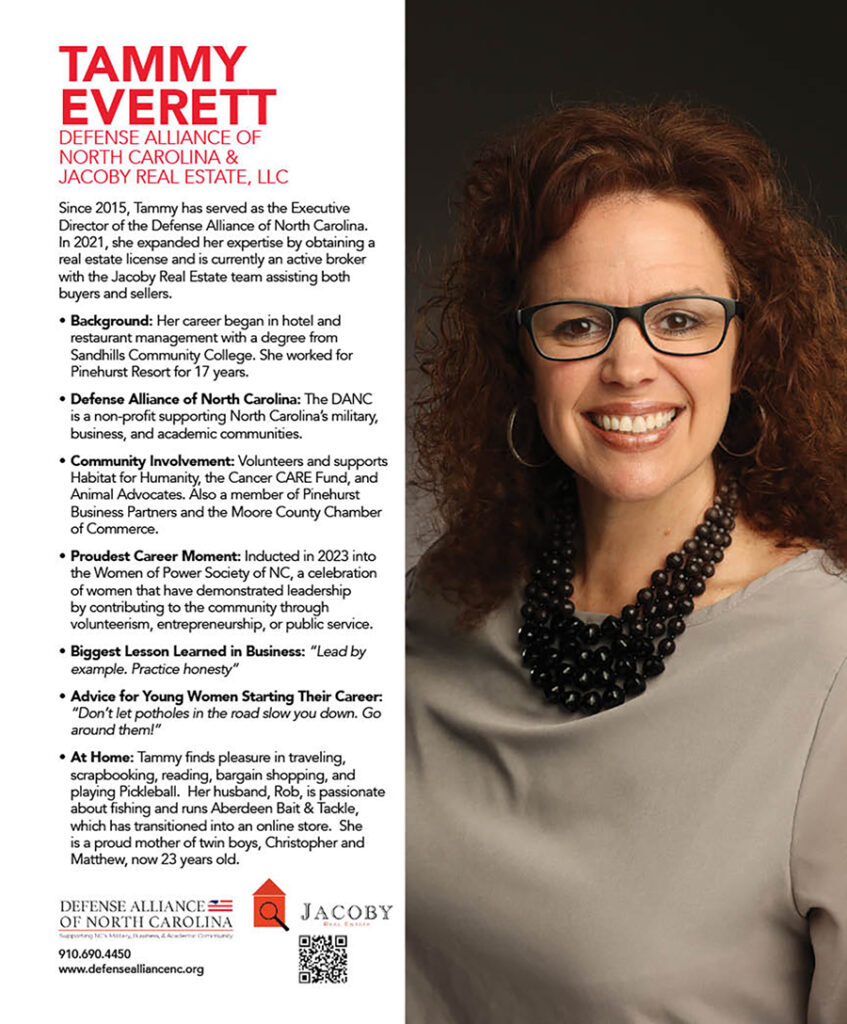

Hooked Up to History

Skydiving with Bush 41

By Amberly Glitz Weber

Photograph by John Gessner

“Sir.”

He didn’t say anything.

“Mr. President?”

No answer.

Time is very important. We’re losing time and altitude. I’m, like, is he dead? Everything’s going through my head right now.

“Sir?”

“Yeah?”

“Sir, you gotta help me get your legs up.”

It was the morning of June 12, 2014. Former President of the United States George H.W. Bush is floating toward the Earth from approximately 8,000 feet over his home of Kennebunkport, Maine, strapped to the chest of retired Sgt. 1st Class Mike Elliott, a former Golden Knight and founder of the independent skydiving team All Veteran Group. The panoramic view of St. Anne’s Episcopalian Church and the Atlantic Ocean stretch out below them. And the side pinnings that allow for a flexible landing position will not loosen.

Maine is a long way from Linden, North Carolina, a little town 45 minutes north of Fayetteville, where Mike Elliott was born and raised. “I had four uncles who were all in the military. My grandfather was a veteran of World War II. I was the only grandchild for many, many years, and my uncles were more like my big brothers. They loved the military, which led to me loving the military,” Elliott says. “My grandfather just had that military soul. He always had the high and tight haircut, the perfect mustache. He was a book of knowledge.”

Working part time at a grocery store in Spring Lake during high school, Elliott saw soldiers walking in and out, pulling on their berets. “Whether it was the green beret or the maroon beret, I knew my destiny was to join the military,” he says. He enlisted after high school and spent a year in Baumholder, Germany, in the mechanized infantry, a titanic change for a kid from North Carolina. “It was white and snowy and I think it stayed that way the entire year.”

His first encounter with the open skies was when he was sent to Fort Campbell, Kentucky, home of the 101st Airborne Division. He became an air assault instructor and stayed in that position until war broke out, deploying as a scout in Operation Desert Shield, Desert Storm. No parachutes there. Instead, he spent his time “doing reconnaissance on a dirt bike in the desert.”

At war’s end Elliott returned to Fort Campbell and secured a post as driver to Gen. John M. Keane, then commander of the 101st. “He always called me ‘good sergeant’ and after 14 months he asked me, ‘What’s next for you, good sergeant?’ I told him I wanted to jump out of airplanes.” In 1991, Keane sent Elliott to Fort Bragg (now Liberty) and the 82nd Airborne Division, where he became a squad leader. Even now he calls it the “toughest job in the military.” After four years, he was transferred to Fort Benning, Georgia, as an airborne instructor. His skydiving destiny was coming closer.

“Walking out onto Fryer Drop Zone I see these four specks with blue parachutes come out of an aircraft,” he says. He watched them land to a precision point in the field. The specks were members of the Golden Knights, the U.S. Army’s parachute team. “I said to myself, there are people in the Army who do that, jump out of airplanes and tell people about the Army? Man, I want to do that.” Determined to get there, Elliott began the process. First he was named Instructor of the Year, an honor that gained him entry to the Fort Benning parachute team, the Silver Wings, a demonstration team that feeds applicants to the Golden Knights. Then he met a challenge he couldn’t muscle through.

“At the time I was really big into weightlifting, just a musclehead. This should have been easy stuff, but I spent 30 jumps trying to relax and get stable. I would flip through the air over and over, and right at pull time I would flatten out on my belly, and deploy my parachute, and that kept me in the program . . . that and I was Instructor of the Year,” he says with a wink.

How does a guy who can’t get stable in the air become team leader of the Silver Wings? “Finally, I realized I couldn’t fight the air. I had to take muscles out of the equation.”

Eight years into his military career he was a sergeant first class and where he wanted to be. “I was living and breathing my dream, which was to become a Golden Knight,” he says. He returned to Fort Bragg and the 82nd as a platoon sergeant, a position he held for two years under a division command sergeant major who didn’t want to lose him to the “pretty boy” parachute team. What began as a stumbling block in his path to the Golden Knights became “the greatest job ever, taking care of 30 kids,” he says. He continued to jump part time with the All American Free Fall team, the 82nd Airborne’s demo team, where he also was appointed team leader.

In 2000 Elliott finally had his chance to try out for the Golden Knights. “I thought I’d done some pretty cool things in the military, but tryouts was an eye-opener. I went in at 205 pounds and came out 185. With 15 to 20 jumps a day, you’re running and you’re rolling, and the attrition was so high.” He shakes his head. “That was one of the happiest moments of my life, getting jacketed as a Golden Knight.”

During his career with the parachute team, Elliott fostered its burgeoning tandem program. “Being able to share my passion for free fall with someone else and see that excitement in their first jump was absolutely amazing. That first year we did a lot, a lot, of tandems. The program really launched and, to this day, I think it is probably the most important element of the Golden Knights,” he says. “When you can take an educator, or a first responder, or a celebrity on a tandem jump, representing the Army in that way, and they see it through our eyes, and get a chance to enjoy that sensation and that passion. It spreads the knowledge about what we do as Golden Knights, but more importantly what we do as soldiers.”

Elliott spent 11 years as a Golden Knight. In 2007, he was the most experienced tandem instructor on the team when he got a call that would alter the trajectory of his life.

“My boss calls me in, and says, ‘C’mon in, close the door. Former President Bush wants to do another jump and we want you to be his tandem instructor.’” Of course, Bush’s first parachute jump was in 1944 during World War II as a Navy pilot shot down on a bombing raid over Japanese-occupied Chichi Jima. He’d gone on to conduct skydives and tandems with both the Golden Knights and the U.S. Parachute Association, marking every fifth birthday after his retirement by strapping on a parachute and jumping from a plane.

“So I walk out of the office, close the door, and it hits me, you’re gonna get to jump with a former president and leader of the free world. One of those moments where you know you can’t screw this up, the whole world’s going to be watching.” The mission had one more twist — it was a secret.

“No one knew. Not even the Secret Service,” Elliott says. “So we have this closed office call. I’m sitting in there, drinking coffee, eating doughnuts with the 41st president. He said, ‘Here’s the deal guys, we’re gonna keep this thing a secret.’ No one knows but Jean Becker (former Chief of Staff).”

They don’t tell Barbara Bush until the day before the jump. “I’m getting ready to do a teleconference with the 41st president. Once I’m done, they say, ‘Mrs. Bush wants to come meet you and the guys who are going to be jumping her husband tomorrow.’ So I’m standing out in front of the team and I see Mrs. Bush coming down the stairs. She had such elegance about her, just gliding down the stairs. She’s tiny, probably 4 foot 2.” He grins at the recollection. “I’m thinking she’s gonna give me a hug, say thank you for taking care of my husband kind of thing. So she walks over, I got this big, cheesy smile on my face. I was looking down at her, and she’s looking up at me. She had no smile on her face whatsoever.

“They introduce us, ‘Mrs. Bush, this is Sgt. 1st Class Elliott, he’s going to be jumping your husband tomorrow.’ And again, I’m sort of pushing my face forward a little bit, still thinking she’s gonna be giving me this big hug right? And she looks up at me and says these exact words: ‘If you hurt him, I will kill you.’ And I chuckled a little bit — she did not chuckle. She turned and walked away.”

Elliott bursts out laughing. “Turned and walked away! And I’m thinking, ‘Wow!’”

The jump was flawless. “I remember he was coming out of the crowd, waving . . . a beautiful landing. I was so grateful to say that I was a member of the U.S. Army, of the Golden Knights, at that moment; to give him that jump, something he loved. He ended up writing me a letter afterward, and he said ‘You made an old man feel young again.’ So that was just the icing on the cake, to have the opportunity to be with such an iconic figure, the 41st president, head of the CIA, world’s youngest Navy pilot shot down in World War II, and I just jumped him out of an airplane in front of a thousand people. Every network in the world was there . . . and I didn’t hurt him, so I didn’t have to face Mrs. Bush.”

Years passed, when Elliott heard from the president again. “He wanted to jump for his 85th birthday, and he requested me by name,” says Elliott. Together with the Golden Knights tandem coordinator Dave Wherley, “my best friend, airborne buddy, my little brother,” Elliott traveled to Kennebunkport for a survey of the jump site. He remembers with perfect recall the time he and Wherley spent with “41.”

“We’re walking around with the president at Walker’s Point, and this guy’s just so humble, you don’t think you’re talking to a former world leader, because he’s just such a nice guy,” says Elliott. After the survey, the president invited the two to join “him and Barbara” for dinner.

“We go into the sunroom, overlooking the water, Dave and me. Soon as we walk in, the president goes, ‘You guys want a drink?’ This is all happening in slow motion. He pours two cocktails out, so we sit there, and we’re talking to Mrs. Bush and the president about jumping. He’s telling us about being shot down, and it’s just one of those moments, where I’m like, wow.”

The next day’s jump came off perfectly. “It was just an amazing feeling to give that to him in front of the world. It wasn’t just me, it was the entire team that made the mission happen. But it was my second successful jump with the president, and after each jump, he writes me a letter. ‘Thanks for carrying all the weight, you’re the best ever. Let’s get working on my 90th birthday jump.’”

Three years later, after more than a decade as a Golden Knight, Elliott was preparing to retire. “The tandem team had been successful and I noticed that a lot of guys would leave the Golden Knights with great skill sets as far as performers in the air, as skydivers, but they wouldn’t jump anymore. They would leave the Golden Knights and just stop jumping.” He shakes his head. “I get it. It’s not the same, but myself and Dave, we were like ‘Man, there’s such potential out there. Let’s start our own team.’”

Together, the two best friends began making their dream a reality. Elliott found sponsors and office space in downtown Fayetteville. A year later, Wherley retired and came on board full time. “I was waiting on Dave to retire,” Mike says. “He was going to be the coordinator, making phone calls and getting us locked in doing shows.” Then, 28 days later, on January 31, 2013, tragedy struck.

Elliott found his friend in his apartment having taken his own life. “It put a hole in my heart,” says Elliott, “but it also put the wind in my sails to stand this team up. This veteran suicide thing is out of control. So if we can do something positive, if we can save one life a month, one life a year, then what we do is a great thing.”

The loss of his friend redefined the mission and goal of the team. By raising awareness about veteran suicide Elliott hoped to build a legacy for his friend and brother. “Dave, he gave us our purpose for the All Veteran Group. When you have a passion for something, and that passion turns into a drive for other reasons, it’s a fusion that’s immeasurable. You know we do this out of passion, but we do it because there’s a possibility it’s going to motivate someone else, give them the strength and courage to say, ‘You know what, I’m gonna continue to live my life. There are veterans out here doing great things who love me. Why should I not want to be here?’”

Moving out to XP Paraclete, a Raeford drop zone, Elliott established new operating headquarters in the freshly dedicated Wherley Building. “I was riding the ebbs and flows of starting a parachute team,” when he got a call from Jean Becker. The same Jean Becker. The former president, now turning 90, had not forgotten his “airborne buddy.” Despite a plague of health concerns, 41 wanted to jump again — and he wanted to do it with Mike and the All Veteran Group.

“Ms. Becker calls me, she says, ‘Mike, you’re not going to believe this, his doctor is saying no, his wife is saying no, 43 (George W. Bush) is saying no, but he is determined.’”

And so Elliott launched six months of preparation, designing specially constructed heavily padded harnesses for the wheelchair-bound president, rigged to carry supplemental oxygen. The All Veteran Group’s plane at the time was a King Air 90, “a great plane, but a tiny door,” not suitable for this jump. Reaching out to the CEO of Bell Helicopter, a veteran and former Army Ranger, Elliott got a “brand-spanking new Bell 429,” transported from Texas to Maine, ready to land on the president’s front yard. “All the moving parts were coming together.”

Until the day before the jump, when Elliott received another call from Becker.

“Mike, we have a problem,” she says. “Mrs. Bush doesn’t want the jump to happen.”

Elliott shakes his head, remembering. “I’m thinking about everything we have done to get to this point but also, ‘I’m gonna kill you’ is in the back of my mind. If Mrs. Bush doesn’t want it to happen we might as well pack up.”

Jean Becker wasn’t finished. “No, no, no, we want you to go and talk to Mrs. Bush,” she said.

“All these people around — two former presidents, a former governor — and you want me, the person she threatened to kill, to talk to her and get her approval to jump her husband tomorrow?”

Becker replied, “Yeah, that’s what we want.”

They left the office together and headed to the main house overlooking the water where they explained the situation to 41. The president interrupted, “I thought we had that all figured out.” The nonagenarian looked at Elliott and said, “Do we both have to go up and talk to her?”

It was then that George W. Bush, “43,” walked out from one of the smaller lodges. “He’s been painting, got paint all over his hands, hair looking all crazy,” says Elliott, “and Ms. Becker says to him, ‘Sir, Mike’s going to go talk to Mrs. Bush and persuade her,’ and he says, ‘Mmmm, I don’t know about that.’ Not much confidence from 43 because Mrs. Bush, she’s the head honcho. What she says is the final answer.”

Becker went in first to prepare Barbara, leaving a disconsolate trio outside on the porch.

“So here I am,” Elliott says, “a little soldier boy from North Carolina, standing here with two former presidents, waiting to go in and get clearance from a former first lady, and I was just like, ‘Man, I can’t believe this is happening.’”

Jean Becker stepped back onto the porch. “Mrs. Bush was looking out the window at all you guys, and she says, ‘I don’t want to talk to any of you.’

“Is she pissed?” 43 asked Becker.

“No, she just doesn’t want to talk to you.” The former first lady was, reluctantly, on board. George W. Bush turned and said, “Mike, you are the man.” He gives Elliott a high-five and went back to his easel.

The weather was marginal the next morning as a team of four people helped lift the 6-foot, 2-inch former president into the helicopter. At 8,000 feet the tandem jumped. “I remember the parachute opening, and once you get the parachute open, you have to loosen things up,” says Elliott. “You’re hooked up to each other at four attachment points, and the two at the hips are really important, because if you don’t get them loose, you won’t have the mobility to lean back and get that perfect landing position.”

With time going by quickly and Bush “not acknowledging anything — I didn’t even know if he was still breathing,” Elliott had only moments to prepare.

“Never got the side connections undone, so now we’re coming in hot. We’re tight together, so I roll over my shoulder onto the ground.” Straightening into position, Elliott aligned himself to take the brunt of the landing with Bush positioned on top of him, Elliott’s body acting as a buffer with the ground.

“I was thinking, I just hurt the president. I say ‘Sir, you OK?’ and then I see, he’s giving me the thumbs up, waving at the crowd. Man, it was the best feeling you could have.” Elliott smiles. “I know that day I made a 90-year-old former world leader happy.”

Another chapter with the Bush family complete, Elliott returned to leading the All Veteran Group. “That jump gave us news on a national level,” he says. It brought badly needed publicity in a niche industry, and the team has continued to maintain a tight schedule. With each year, they add more shows, more jumps, raising awareness for veterans’ issues. For a team composed of more than 80 percent former Golden Knights, they maintain their connection via train-the-trainer exchanges and internships for soldiers in need of extra support.

The All Veteran Group conducts an annual Toys for Tots event at its home base in Raeford and travels the country supporting the home-building nonprofit U.S. Veterans Corps on ceremony days. Today, their sponsor is American Airlines, and they are the official skydiving team of the Carolina Panthers.

It’s the 11th year of the team, and the schedule is relentless. “It’s demanding but I enjoy it so much. It’s relaxing — I don’t like sitting at home,” says Elliott. “I’m comfortable in this environment because I understand why we do what we do, and this passion is real and I love it and I’ll do everything that I can and continue to do it for as long as I can.”

Last year saw the All Veteran Group jump at 137 shows. The 2024 schedule has been filled with cross-country and international flights, from Texas in March jumping a 102-year old World War II veteran, to Normandy in June for a landing on Omaha Beach. He’ll be back to Texas in mid-June for another special celebration for what would have been George H.W. Bush’s 100th birthday.

Though 41 has passed on, this party will be special for Elliott, as he conducts tandem skydives with the Bush grandchildren, honoring their late grandfather. “They’re super nice people. They treat everybody the same. That’s how I remember the 41st president,” Elliott says.

So, what is it about the 60 seconds in free fall that makes it so alluring, particularly to veterans? Is it just the airborne legacy or is there something more? Elliott eyes the mementos of a long career spent in service to others, memorabilia from 41, and his best friend David Wherley’s life-sized cutout standing guard by the front door of his Raeford office. He thinks about his final jump with a president.

“It was a picture perfect moment, in between St. Anne’s Church and Walker’s Point overlooking the water, and I think at that moment, he was just kind of doing an internal shot of his life. He was just so calm and at peace.”

The stillness in that stretch between sea and sky can offer a few seconds of reflection for us all. PS

Aberdeen resident Amberly Glitz Weber is an Army veteran and freelance writer.