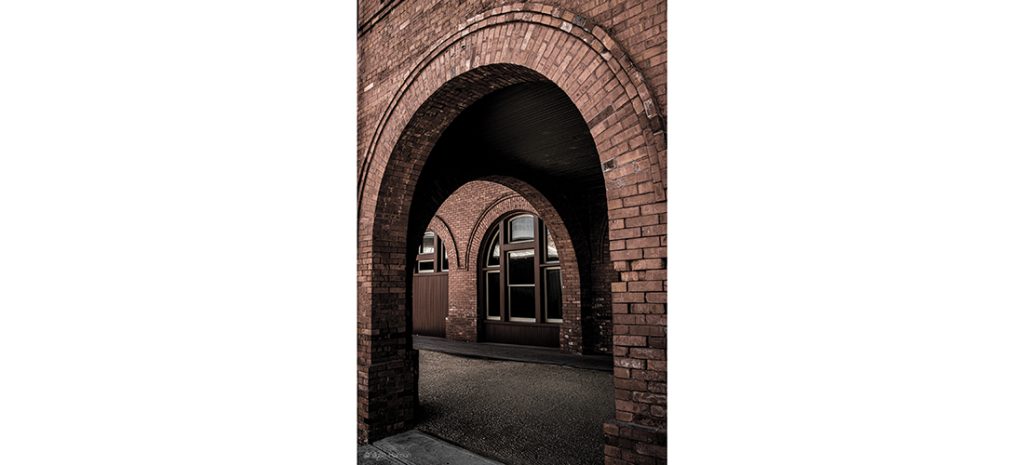

Horton Smith and his abbreviated Pinehurst employment

By Bill Case • Photographs from the Tufts Archives

An above-the-fold headline in The Pinehurst Outlook on May 30, 1941, screamed, “HORTON SMITH SIGNS PINEHURST CONTRACT.” Smith, regarded as one of the brightest stars in professional golf’s galaxy, would soon be making his way to the Sandhills to work in a promotional capacity for the Pinehurst Country Club. He was coming in hot, having won one official and two unofficial events, all in the South, earlier that year. By accepting the position, he immediately became the highest profile employee in the club’s history with the exception of his new supervisor, Donald Ross, the club’s manager.

“There will be plenty for Horton to do here,” said the venerable Ross. “He will have what might be termed a roving assignment to aid us in making our golfing friends enjoy their visits in Pinehurst.” This meant the 33-year-old native of Joplin, Missouri, would primarily be golfing and hobnobbing with resort guests and playing occasional exhibition matches.

Smith would not be giving lessons. “That assignment,” Ross explained, “will be handled by Harold Callaway and Bert Nichols, who have been here for many years.”

Horton and his wife of three years, Barbara Bourne Smith, had committed to making Pinehurst their “permanent” home from November until May — the months the resort was then open for business. For the 1941-42 winter season the couple resided at the Carolina Hotel. In the immediate wake of their newfound affiliation, Smith would continue to play on the PGA circuit, where the man nicknamed the “Joplin Ghost” would be introduced as representing Pinehurst Country Club.

Although the article made no mention of his involvement, it is certain that Bob Harlow, the owner and editor of The Outlook, played a key role in orchestrating the relationship. A born salesman and promotor, Harlow had previously managed the PGA’s rather loosely organized “tour” and served as business agent for several top pro golfers, most notably Walter Hagen. Though busy running The Outlook, Harlow kept his hand firmly in the promotional game as the director of publicity for the Pinehurst club and resort.

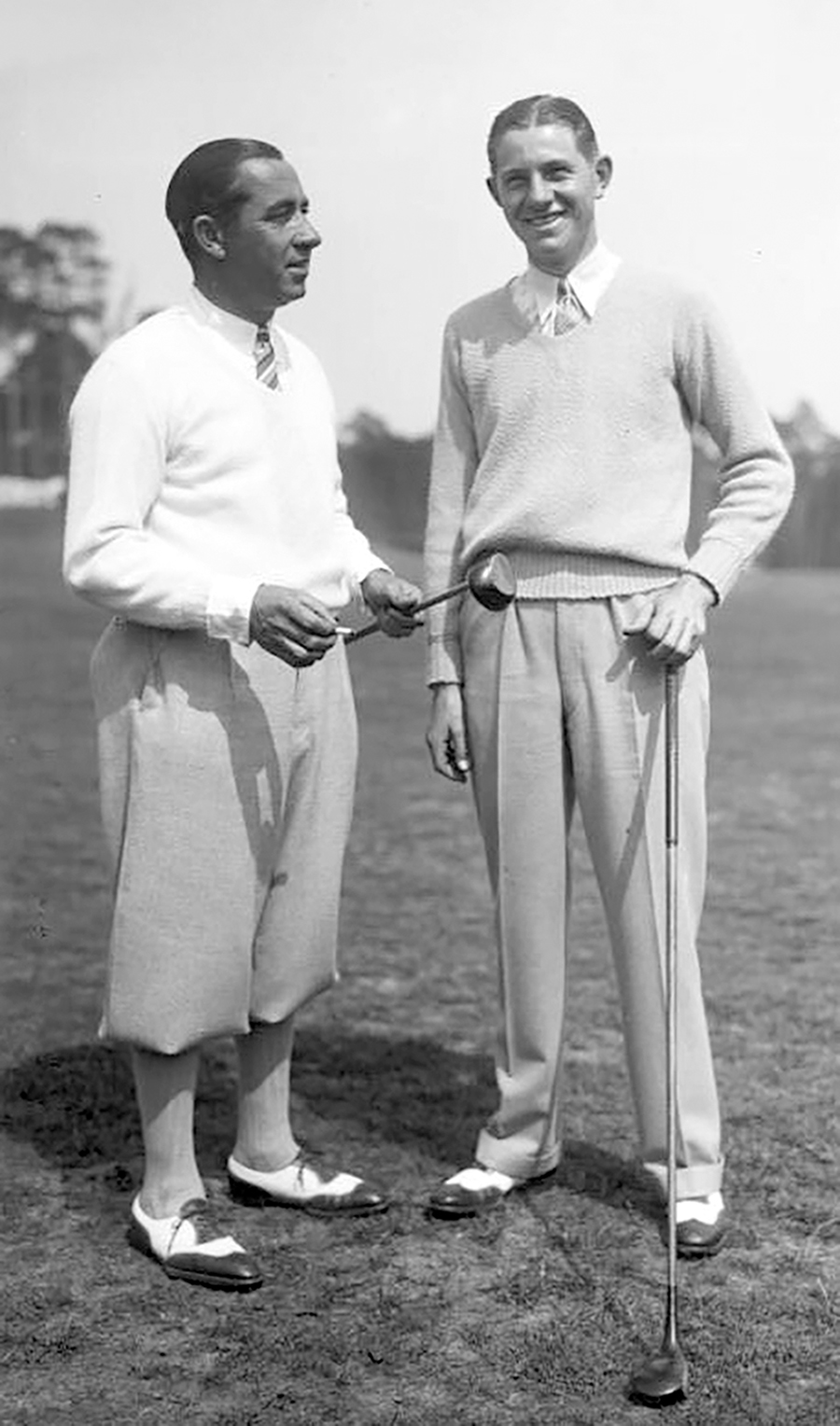

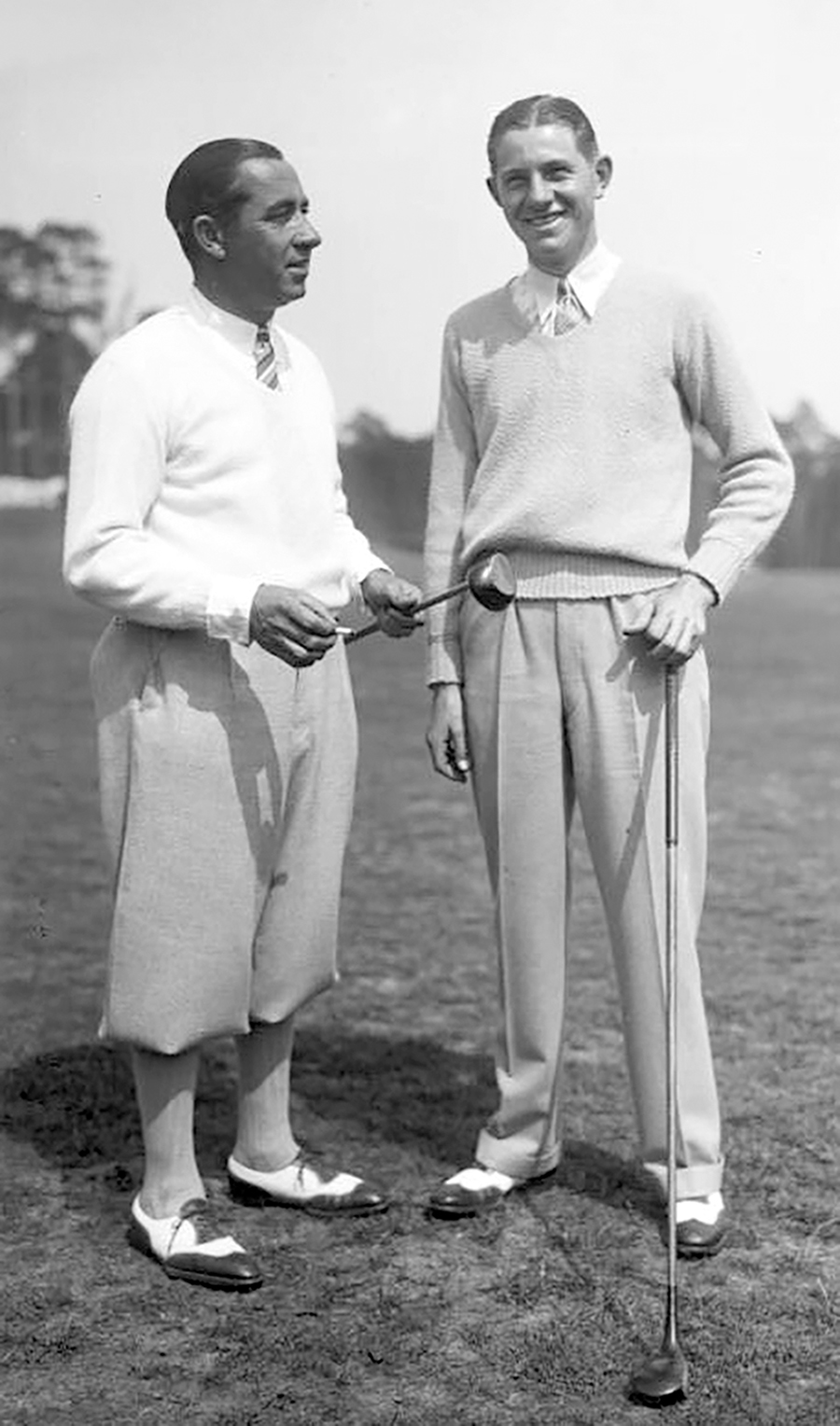

Harlow and Smith first encountered one another in 1929, when Horton, only 21, won an eye-popping nine tournaments — eight PGA tour titles and the French Open — just three years after turning professional. His collection of victories that year included Pinehurst’s prestigious North and South Open, then contested on sand greens. Hagen, pro golf’s ultimate showman, took note of the young phenom’s early successes and decided he would make an ideal exhibition opponent. The Haig’s agent, Harlow, signed Smith to play 100 matches against Hagen at courses ranging from New York to Missouri and across the border in Canada.

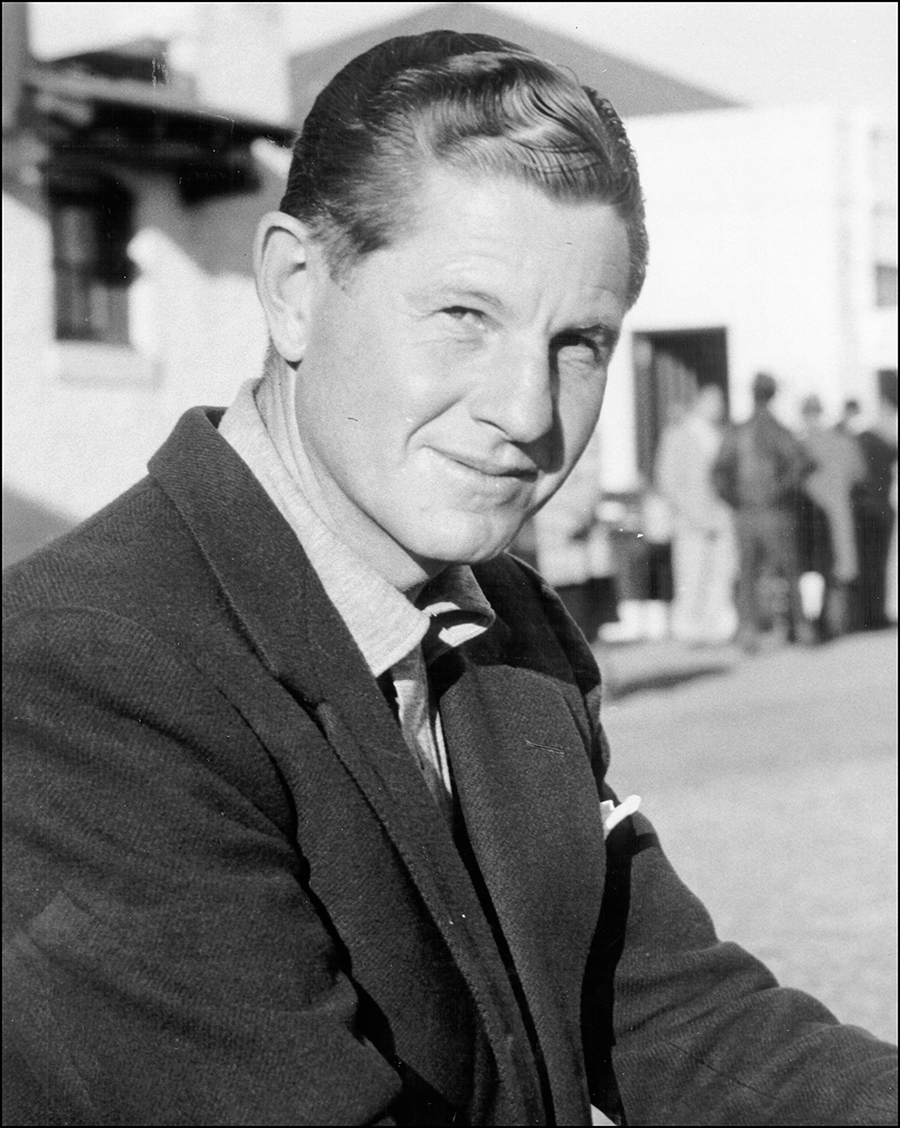

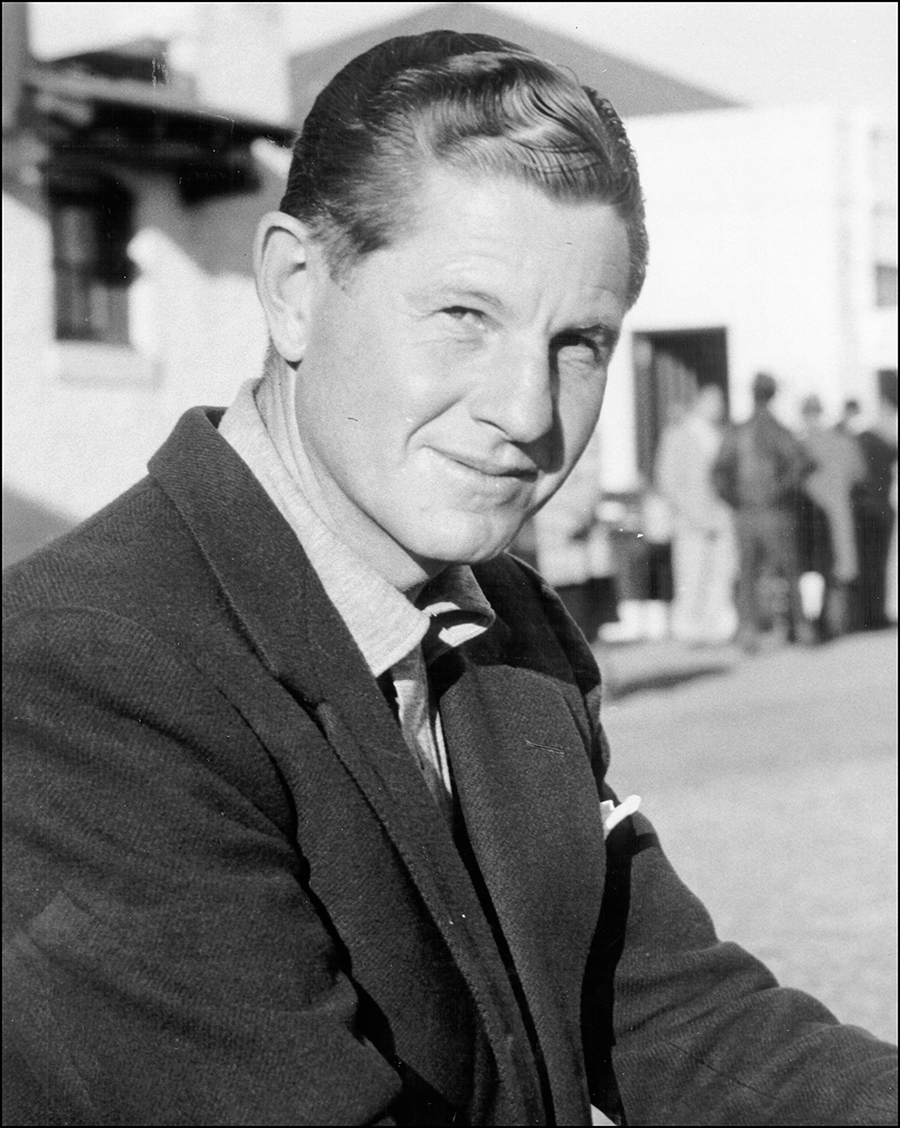

As Marian Benton, Smith’s biographer, puts it in her book The Velvet Touch, it would be difficult to “imagine two more diverse personalities than those of the ‘golden boy’ of golf (Smith) and the ‘crown prince’ of the links (Hagen).” At 6 feet, 2 inches tall and handsome as a Hollywood leading man, the mannerly and teetotaling Smith was typecast as the quintessential All-American Boy. In contrast, Hagen played the roguish and carefree carouser, though it is believed he poured more drinks into potted plants than he consumed — at least during his playing days. Despite vast differences in style and personality, the two stars became lifelong friends, hopscotching, along with Harlow, from course to course.

After the far-flung exhibition tour, Smith continued his winning ways, gaining a reputation as the tour’s finest putter. During the 1930s, he won 20 times (two were unofficial), capturing a second North and South title in 1937 — this time on No. 2’s new grass greens. But his greatest triumphs came in Augusta, Georgia. In 1934, he won the first Masters Tournament, then known as the Augusta National Invitation Tournament. Atop the leaderboard all four rounds, Smith’s total of 284 was one stroke better than Craig Wood, who would be victimized the following year by Gene Sarazen’s “Shot Heard ‘Round the World” on the 15th hole. Smith’s lengthy birdie putt on the 17th hole of the final round proved to be the clincher.

Two years later, he won the tournament again, edging “Lighthorse Harry” Cooper — the nickname invented by Damon Runyon — when poor weather forced 36 holes on Monday. In the afternoon Smith chipped in for birdie on the 14th, then birdied the 15th and finished with two pars to win the first prize money of $1,500.

Like Harlow, Smith segued into business activities related to golf. President of his local PGA section in 1935, Smith served as an active member on an array of PGA committees. The Missouri native also arranged exhibitions for the Spalding Company’s stable of professionals that included himself, Lawson Little, Jimmy Thomson and Cooper. He rarely passed up an opportunity to promote golf. Typical was Smith’s appearance at the Sandhills Kiwanis Club six months prior to his hiring by Pinehurst Country Club. In his remarks, the two-time Masters champion urged the Pinehurst, Southern Pines, Pine Needles and Mid-Pines golfing communities to “pull together to make this the golfing center of the world.”

When Horton and wife Barbara arrived in Pinehurst early in November ’41, they made an immediate splash. Harlow saw the Smiths in the Carolina Hotel dining room and gushed that they were “the most striking couple on whom my eyes ever have feasted.” Barbara was more than just vivacious — she was heiress to Singer sewing machine money. Grandfather Fredrick Gilbert Bourne’s savvy investments and long tenure as president of the Singer Manufacturing Company had built generational wealth for the family.

Alfred Severin Bourne, Fredrick’s son and Barbara’s father, was an excellent amateur golfer. As upper-crust society often does, the Bournes moved with the seasons: summers at their 40-room estate in Washington, Connecticut; and winters in Augusta, Georgia, where Alfred became a charter member of Augusta National Golf Club and a friend of Bobby Jones.

When Augusta National was in danger of failing during the Great Depression, it was Bourne who furnished lifeline funds to keep the strapped club afloat. Barbara also became an avid golfer, good enough to have once bested the legendary Babe Didrickson. Introduced to one another during the 1936 Masters Tournament — the year of Smith’s second victory — the couple dated intermittently during the ensuing two years before marrying in 1938.

The Smiths were happy during their winter stay in Pinehurst, immersing themselves in Pinehurst golf. Barbara joined the Silver Foils — the oldest existing women’s golf society in America — and quickly made her presence felt, winning a better-ball competition when she and her partner carded a score of 72. Meanwhile, the Joplin Ghost joined the Tin Whistles, the Pinehurst Country Club’s pre-eminent men’s golfing society. His father-in-law, Alfred, had become a member of the society the previous year. As a regular dues-paying Tin Whistle, Smith was eligible to play in the society’s frequent tournaments, though he had to spot a daunting number of handicap strokes to his fellow members. In his initial competition with the society, he partnered with S.A. Strickland (grandfather of Pinehurst mayor John Strickland) to win a four-ball event. He would later set his sights on capturing one of the Tin Whistles’ major tournaments, the James Barber Memorial. Playing Course No. 2, Smith carded a brilliant 67. However, his plus-4 handicap required adjusting his net upward to 71, tying the net score of Charles Murnan, a 21-handicapper from Leesburg, Virginia.

Several days later, Smith and Murnan settled the deadlock with an 18-hole playoff over Course No. 3. On the front nine, Smith shot a sensational 32 to Murnan’s 45, making up 13 of the 25-stroke handicap differential. Smith charged home on the back with another 32 (his best-ever score on No. 3) but it wasn’t enough. Matching shots with a two-time major champion, Murnan posted a 42 on the back nine. His resulting net score of 66 beat Smith by two strokes.

In January 1942, with America now on a war footing, Smith traveled to California, where he played in the Los Angeles Open and the Bing Crosby National Pro-Am. He led the field early at L.A. before fading from contention. During his trip, Smith wired reports to Pinehurst regarding happenings on tour, and Harlow published the musings in The Outlook. “They charged $2.50 per 18 holes and $1.00 for practice for caddies at the L.A. Open,” complained Smith, a notorious penny pincher. “If my caddie starts putting better, I will trade places with him.”

In another dispatch, Smith noted that “there is surprisingly little evidence of war here,” though he acknowledged that the government’s decree prohibiting manufacture of golf balls was already being felt. “Players have been scrambling a bit for golf balls, being more careful and not using new ones for practice rounds.”

The Smiths returned to Pinehurst for the remainder of the season. Barbara completed her stay in style, capturing the first flight title (one rung below championship flight) at the Women’s North and South Amateur. Donald Ross presented the trophy to a delighted Mrs. Smith.

Despite the war, the PGA tour continued operating throughout the spring and early summer of ’42. Smith, along with other big stars like Ben Hogan, Sam Snead and Byron Nelson, competed in April’s Masters Tournament. Smith finished fifth, seven shots behind Nelson.

On Thursday, April 30, the Smiths hosted three other couples at a farewell dinner party at the Carolina Hotel. The following day they left Pinehurst and headed south to Augusta to visit her parents. The Outlook reported that while Smith planned on playing a few tournaments during the summer, he anticipated being in the Army by fall. Though it was suggested that Mrs. Smith might make Pinehurst her winter residence if Mr. Smith was in the service, there were no foreseeable circumstances likely to result in Smith’s returning to his job at Pinehurst. With all of America’s resources, including golf courses, subordinated to war needs, Pinehurst had as much use for a goodwill ambassador as it did a lamplighter.

In December 1942, Smith enlisted in the Army Air Corps, receiving his basic training at Jefferson Barracks in Missouri, then attending Officers Candidate School in Miami Beach. A fellow graduate of the school, Pinehurst friend and 1940 U.S. Amateur champion Dick Chapman, arranged for Smith’s assignment to Knollwood Field near Pinehurst, where the two-time Masters champion served as a general’s aide. He and the general didn’t get along, however, and Smith requested and received a transfer to Seymour Johnson Field in Goldsboro, North Carolina. In the role of special services officer he managed that base’s entertainment facilities, booking U.S.O. shows and managing the archery range, bowling alleys and golf range.

Barbara became pregnant in the fall of ’42 and wanted to be in Goldsboro with her husband, but Horton claimed the spartan conditions at the base weren’t suitable. She acquiesced and stayed with her parents. Though the Smiths rejoiced over the birth of their son, Alfred Bourne Smith, on June 30, 1943, Barbara resented Horton for insisting on what she considered an unnecessary separation.

After the Allies recaptured France and began the final advance to Berlin, Lt. Smith was redeployed to Paris, where he managed professional and amateur golf tournaments involving fellow professional athletes like boxer Billy Conn and golf standouts Lloyd Mangrum, Chick Harbert and his old cohort Hagen. The Outlook published a message from Smith reporting his “very interesting experience seeing much of southern Germany, France, England and Scotland and assisting in two big Army tournaments in Paris and St. Cloud.”

Smith sailed home in November 1945. Prior to his return, the unhappy Barbara had obtained a divorce in Reno, Nevada. The Smiths were far from alone in experiencing marital discord in the aftermath of the war. Breakups of G.I. marriages occurred with startling frequency. In 1946, the New York Times disclosed that one-fourth of the returning soldiers were “entangled in divorce proceedings.”

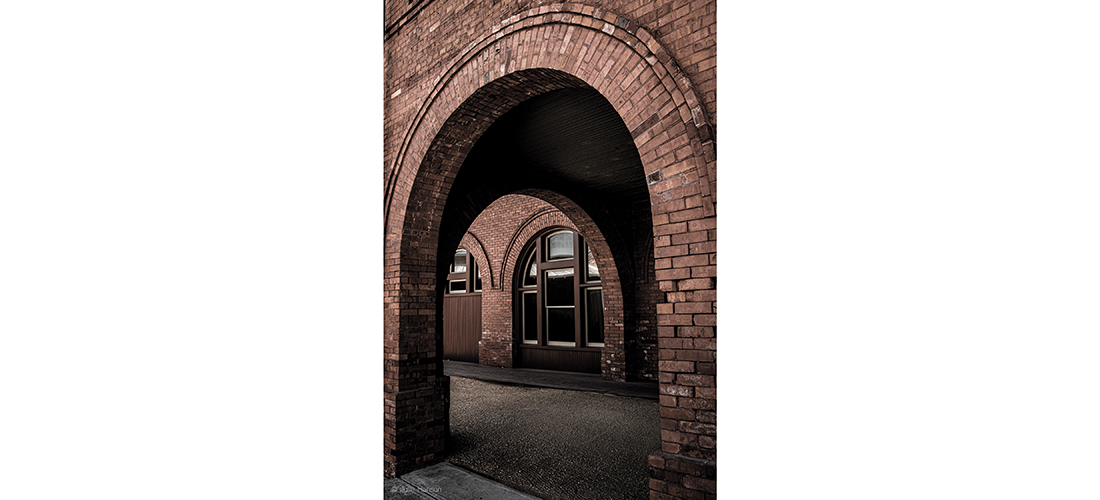

Walter Hagen and Horton Smith

In March 1946, Smith became the golf professional at the Detroit Golf Club, succeeding Alex Ross, Donald’s brother. Immersing himself in the affairs of the club and the Michigan PGA, Smith greatly reduced his tournament schedule. By the time he turned 40 in 1948, having faded from the ranks of top touring pros, he was content with his club job and relatively unperturbed with the decline of his play.

Meanwhile, Barbara, who had relished golfing in the Sandhills, moved into a stately home in Pinehurst’s Old Town area, residing there during the cooler months with 2-year-old Alfred. Living nearly 700 miles from Pinehurst, Smith seldom visited his son. When Barbara married local Sandhills businessman John von Schlegell in 1948, it became increasingly difficult for Smith to sustain a lasting relationship with Alfred, who was ultimately adopted by von Schlegell.

Smith never remarried, confiding to his biographer Benton, “I don’t know whether I’m too lazy, too old, too tired, or afraid (to get married again), but perhaps that is why I take on so many other things.” Those other things included a three-year stint as national secretary of the PGA of America, and beginning in 1952, another three years serving as the organization’s president. In the latter capacity, Smith received credit for his diplomatic balancing of the conflicting interests of the club pros and the touring professionals.

But Smith’s presidential tenure proved far more controversial than the competing interests of the membership. Shortly after assuming the presidency of the PGA, Smith became embroiled in a dispute at the San Diego Open that would have long-lasting implications. A tournament sponsor, the San Diego County Chevrolet Dealers, invited former heavyweight boxing champion (and avid amateur golfer) Joe Louis to play in the event. The sponsor figured the presence of the popular “Brown Bomber” would hype attendance.

Louis was no slouch as a player. The beneficiary of excellent instruction from Black professionals Teddy Rhodes and Bill Spiller, the champ often scored in the mid-70s. The 39-year-old Spiller also expected to be in the tournament having survived a 36-hole qualifier.

But Smith and the PGA blocked Louis’ and Spiller’s entries, invoking the “Caucasian-only” clause in the organization’s bylaws. An irritated Louis, generally reticent in decrying racial discrimination during his long reign as champion, took a firm stand. “I want the people to know what the PGA is,” he complained. “We’ve got another Hitler to get by,” he said, referencing Smith.

In a national broadcast, radio commentator Walter Winchell added fuel to the growing conflagration, excoriating the PGA and Smith for their treatment of both Louis and Spiller. Winchell pointed out that the champ had honorably served his country during the war, but was now being branded as unqualified to wield a golf club in San Diego.

Now the target of a media firestorm largely of their own making, Smith and the PGA backpedaled, construing the “Caucasians-only” provision to apply only to professional golfers. This revised interpretation would allow Louis, an amateur, to compete. But the ruling was no help to Black pros like Spiller, still victimized by the PGA’s Catch 22 reasoning: To be eligible to play in a PGA-sanctioned event, a professional golfer had to join the PGA, but Black pros were not allowed in. Spiller remained barred from the San Diego field.

When tee times were announced for the first round at San Diego, it caught everyone’s attention that Smith and Louis would be playing together — a pairing surely suggested by Smith himself. The recent antagonists chatted amiably throughout the round. Louis surprised many onlookers by carding a respectable 76. Smith shot 73. The champ’s 82 in the second round resulted in his missing the cut by eight strokes.

But the brouhaha was far from over. The grievances of Spiller and his fellow Black pros were still unresolved. Smith hastily proposed a new rule that would allow a local tournament sponsor and host club to submit a supplemental list of players to invite to their tournament. If a sponsor and club chose to include Black pros on its list, they could compete. The PGA board adopted the policy prior to the following week’s Phoenix Open, and several African Americans, including Spiller, teed it up in the tournament. This incremental step still left Black pros in the unenviable position of needing to lobby tournament sponsors and host clubs just to have a chance to play. Moreover, many private clubs hosting tournaments had no interest in inviting Black players.

Smith publicly indicated he would seek to eliminate the “Caucasian-only” provision. But when his presidency came to an end in 1954, the discriminatory rule still remained. Smith was not alone among PGA higher-ups in slow walking its elimination. It took legal action by the California state attorney general before the PGA leadership relented and dropped the blatantly discriminatory clause in 1961. Only then did pros like Charlie Sifford experience a degree of freedom in planning their schedules, but the change came too late for aging Black golfers like Spiller and Teddy Rhodes, whose best playing years were behind them.

Unfortunately for Smith, he was no Branch Rickey — the Brooklyn Dodgers’ magnate who in 1947 defied his fellow baseball owners by elevating a Black player, Jackie Robinson, to the major leagues. Smith, even if he had wanted to, likely would have had difficulty persuading a majority of the PGA Board of Directors to drop the Caucasian-only clause. But irrespective of his mindset, Smith’s failures to act as a strong advocate for the interests of Black pros and to lay the groundwork for their eventual admission to the PGA’s ranks would significantly damage his legacy.

Pete McDaniel, who wrote for Golf World and Golf Digest for nearly 20 years and is the author of Uneven Lies: The Heroic Story of African-Americans in Golf, had this simple thought to offer: “Smith missed his chance to be a civil rights hero.”

In 1957, Smith started suffering from Hodgkin’s disease. The onset of his illness did not prevent him from working as the professional at Detroit Golf Club, where he was beloved by the membership. And, as a former Masters champion, he continued to play the tournament. In his final Masters appearance in 1962, he labored through two rounds in significant pain. A concerned Bob Jones offered him the use of a golf cart, which he declined.

Smith passed away in 1963 at the age of 55. His ex-wife and his son would likewise die young — Barbara at age 63, and Albert (who became an engineering graduate of Georgia Tech and an airline pilot) in a private plane crash at age 38.

In 1961, Smith received the Ben Hogan Award, presented to a golfer who overcomes a physical handicap while continuing to contribute to the game. In 1962, he was named recipient of the United States Golf Association’s Bob Jones Award, its highest honor. Following his death, the PGA of America established the Horton Smith Award, designed to honor members rendering outstanding contributions to professional education. The Joplin Ghost was inducted into the World Golf Hall of Fame in 1990.

Thirty years later, in 2020, the Horton Smith Award was renamed the PGA Professional Development Award. PGA President Suzy Whaley explained why: “In renaming the Horton Smith Award, the PGA of America is taking ownership of a failed chapter in our history that resulted in excluding many from achieving their dreams of earning the coveted PGA member badge and advancing the game of golf.”

Sixty years after Smith’s death, the simple act of changing the name of an award would be the last ripple in the pond of those things done, and left undone, in the lifetime of a champion. PS

Pinehurst resident Bill Case is PineStraw’s history man. He can be reached at Bill.Case@thompsonhine.com.