Meaningful Happiness

When you think about it, the ordinary becomes extraordinary

By Jim Dodson

I bumped into a friend in the produce section at the market. We had not seen each other since the start of the pandemic — well over a year ago, if not longer — long enough for me to briefly forget her name, though maybe I was just having the proverbial senior moment.

In any case, when I asked how she’d been, she simply smiled. “Like everyone, it’s been pretty challenging. But, also kind of revealing. It may sound funny, but I discovered that picking beautiful vegetables to cook for my family makes me really happy. Previously, shopping seemed more like a necessary chore than a privilege. I guess I’ve learned that the ordinary things provide the most meaningful happiness.”

We wished each other safe and happy holidays and said goodbye. She went off to the organic onions and I went in search of the special spiced apple cider that only comes round during the autumn holidays — an ordinary thing, it suddenly struck me, that provides “meaningful” happiness to my taste buds. For what it’s worth, though too late to count, I also suddenly remembered my friend’s name: Donna.

Quite honestly, in all the years I’ve steeped my tin-cup soul into the works of great spiritual teachers, classical philosophers, transcendental thinkers, Lake District poets and street-corner cranks, I’d never come across the phrase meaningful happiness.

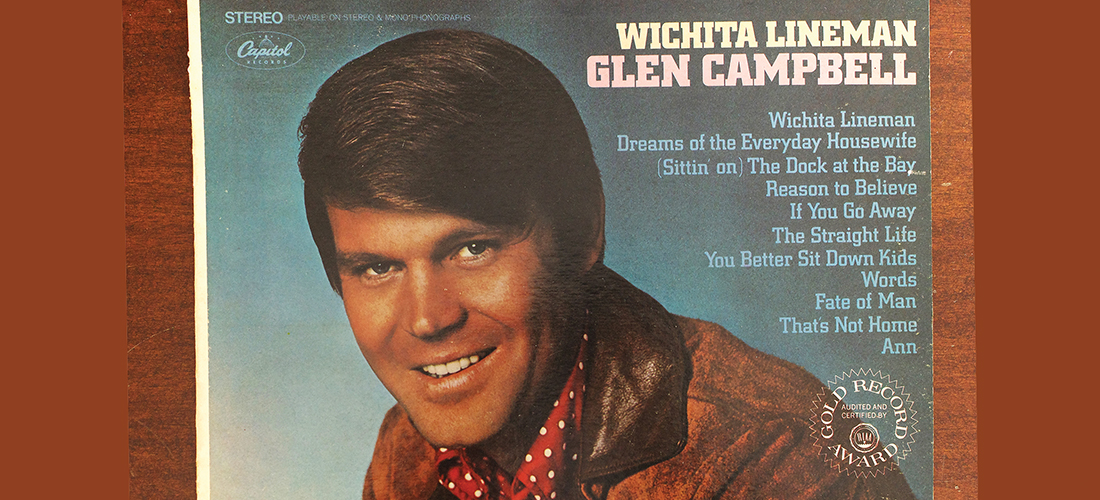

But suddenly — like an ear-burrowing TV jingle or a favorite song from the 1970s — I couldn’t get the idea of it out of my head.

Mankind’s search for happiness and meaning, of course, probably constitutes the oldest quest on Earth, beginning with a fabled naked couple in a heavenly garden, though as any ancient sage worthy of his or her plinth will tell you, true happiness is not something you can acquire from the outside world. Even a fashionable fig leaf can only cover so much.

Objects and possessions can certainly provide a shot of pleasure, but they invariably lose their power to possess us somewhere down the line as rust and dust prevail. At the end of the day, as our wise old grandmothers patiently advised, true happiness can only come from the way you think about who you are and what you choose to do. As a famous old Presbyterian preacher once remarked to me as we sat together on his porch on a golden Vermont afternoon: “What we choose to worship, dear boy, is what we eventually become.”

This curious idea of meaningful happiness, in any case, struck me as a highly useful tool — a way of defining or, better, refining — what kinds of people, things and moments in life are worthy of our close attention in a world that always seems to be beyond our control and on the verge of coming apart at the seams. For most of us, like my friend Donna’s awakening among the vegetables, the art of discovering meaningful happiness simply lies in recognizing the ordinary people, things and moments that fill up and grace an average day.

My gardening hero, Thomas Jefferson — “I’m an old man but a new gardener,” as he once wrote to a friend — was an inveterate list-maker. And so am I.

So, naturally, I began taking mental inventory of the blessedly small and ordinary people, things and moments that provide meaningful happiness in a time like no other I can recall.

I’m sure — or simply hope — you have you own list. Here’s a brief sampling of mine:

Rainy Sundays give me meaningful happiness. The heavens replenishing my private patch of Eden. No fig leaf needed.

Speaking of which, I’ve spent most of the pandemic building an ambitious Asian-inspired shade garden in my backyard, though probably more Bubba than Buddha if you want to know the Gospel. Even so, it’s granted me great peace and purpose, untold hours of pondering and planning, no small amount of dreaming while digging in the soil, delving in the soul, bringing an artist who works in red clay a little bit closer to God’s heart.

Unexpected phone calls from his far-flung children provide this papa serious meaningful happiness. They grew up in a beautiful beech forest in Maine, assured by their old man that kindness and imagination could take them anywhere in the world. Today, one lives in Los Angeles and works in film, the other is a working journalist in the Middle East. They are telling the stories of our time. This gives the old man simple joy from two directions, East and West.

Courteous strangers also make me uncommonly happy these days — people who smile, open doors for others, wear the world with an unhurried grace. Ditto people who use turn signals and don’t speed to make the light, saving lives instead of time; those who realize the journey is really the point. For this reason, I always take the back road home.

Mowing the lawn for the first time in spring makes me surprisingly happy, as does mowing it for the final time in autumn, bedding down the yard.

In summer, I love nothing better than an afternoon nap with the windows wide open; or watching the birds feed at sunset with an excellent bourbon in hand, evidence of a growing appreciation for what our Italian friends call Dolce far niente — “The sweetness of doing nothing.” Ditto golf with new friends and lunch with old ones, early church, old Baptist hymns and well-worn jeans. My late Baptist granny would be appalled.

Let me be clear, eating anything in Italy makes me wondrously happy — for a few blessed hours, at least.

Watching the winter stars before dawn makes me blessedly happy, too, along with wool blankets, the first snow, homemade eggnog, the deep quiet of Christmas Eve, the mystery of certain presents, long walks with the dogs, writing notes by hand and my wife’s incredible cinnamon crumb apple pie.

This list could go on for a while, dear friends. It’s as unfinished as its owner.

But time is precious, and you have better things to do this month — like shop, eat and be merry with the friends and family you may not have been with in years.

Let me just say that I hope December brings you true meaningful happiness.

Whatever that means to you. PS

Jim Dodson can be reached at jwdauthor@gmail.com.