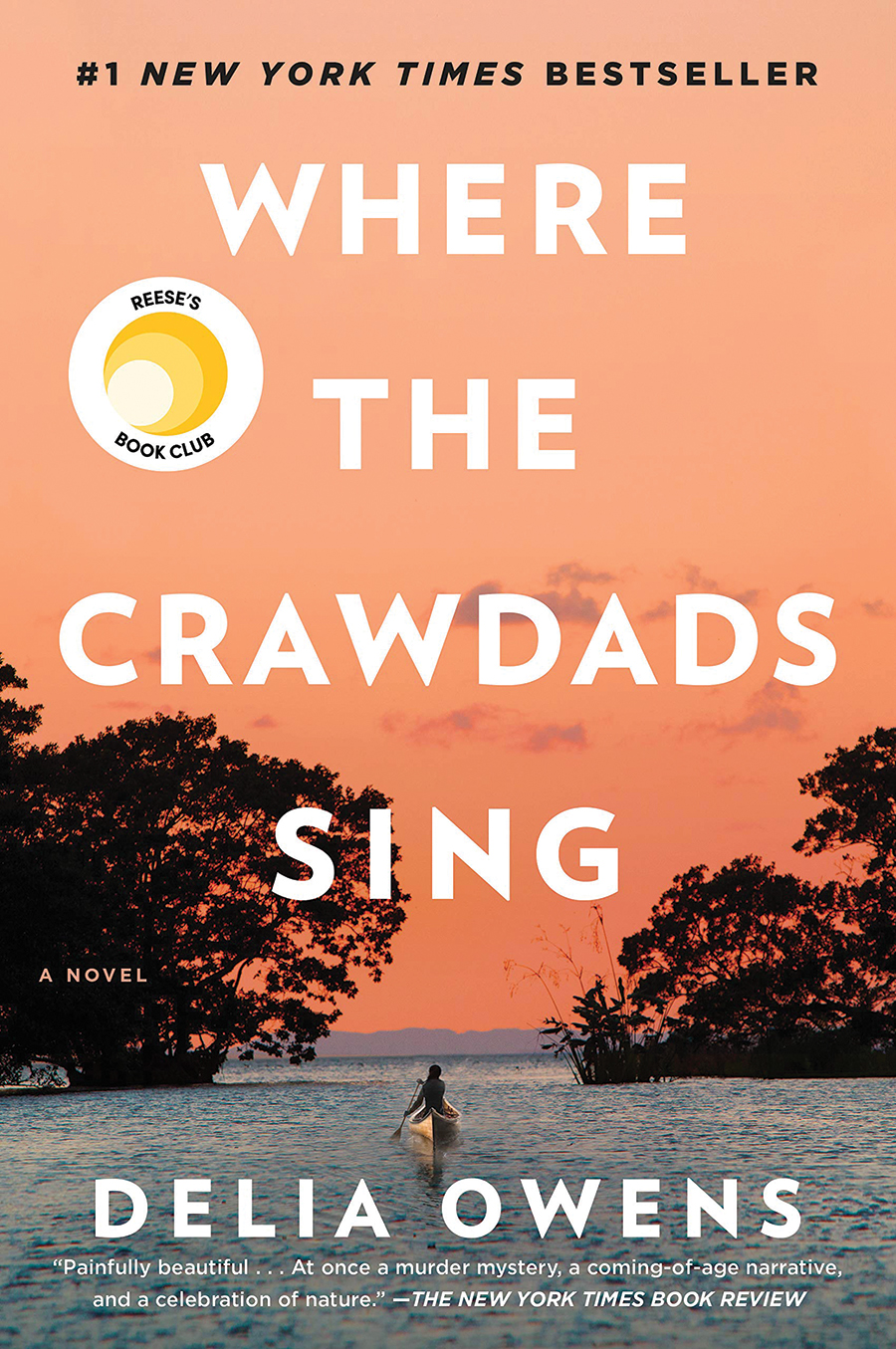

Making of a Marsh Girl

Praise for a North Carolina tale

By D.G. Martin

For almost a year now, Delia Owens’ Where the Crawdads Sing has been at the top of The New York Times best-seller list, usually at No. 1.

North Carolina likes to be first at everything. Freedom. Flight. Basketball. Books. So, some of us have been bragging because Crawdads is set in North Carolina. Most of the action takes place in the fictional coastal town of Barkley Cove and the surrounding marshes, coves and ocean waters. There are side trips to real places such as Greenville and Asheville.

Others complain that the book’s geography is confusing, that the main character is unbelievable, that the framing of the African-American characters and their dialect is faulty, and that the storyline is broken and contrived.

However, the book’s many fans argue that Crawdads is genuine literary fiction in light of its strong and lovely descriptions of nature’s plants and creatures. They continue with praise about the book’s compelling murder mystery that has an unexpected ending and gives readers a superior entertainment experience. They applaud the coming-of-age story of the book’s central character, Catherine Clark, or “Kya.”

Kya was abandoned by her family as a child and lived alone in a shack in the marshes miles away from town. People in Barkley Cove think she is weird, keep their distance, and call her “the Marsh Girl.” She spent only one day in school and cannot read or write. However, because she is smart and diligent, she learns about the nature of the marshes.

When Kya meets Tate Walker, a young man from Barkley Cove, he senses her strengths and shares her love of plants and animals. He teaches her to read and write. They fall in love.

When Tate leaves Kya behind to study science at UNC Chapel Hill, she is devastated. Later, she rebounds to the seductive charms of Chase Andrews, a town football hero and big shot. Their secret affair is interrupted by Chase’s marriage to another woman, and Kya is again distraught.

Overcoming these disappointments, Kya leverages her reading, writing and self-taught artistic talents to record the natural world that surrounds her. When Tate, now a scientist, returns to her life, he persuades her to submit her work for publication. The book is a great success, and she writes and illustrates several more.

All this is background for the story that begins when Kya is grown and her former lover, Chase Andrews, is found dead at the bottom of an old fire tower. Kya is a suspect and is ultimately charged, arrested, put in prison and tried for Chase’s murder.

The evidence against her seems flimsy at first. But incriminating facts pile up, including her angry response to the married Chase’s attempts to seduce her. But she has a strong alibi. The author’s deftness in setting up this situation, and resolving it smoothly, has helped make it a best-seller.

A remaining mystery is how and why Owens, the author of two successful non-fiction books about the African natural world, came to write Crawdads.

After studying and writing about animal behavior, as she explained on UNC-TV’s North Carolina Bookwatch in September, “I wanted to write a novel about how much we know about how animal behavior is like ours. It can help us learn about ourselves. So I came up with this idea of writing this novel about a young girl who is forced to live outside of a social group. She’s abandoned. She’s never totally alone, but she has to spend a lot of time alone, and how does that affect her behavior? That is the question of my novel. Because Kya doesn’t have any girlfriends, she is missing something. She’s lonely, she’s isolated, and when people are forced to live in that sort of situation they behave differently.

“Kya was raised in the wild coastal marsh of North Carolina. She was born in the 1940s and lived through the 1950s and on, and so I chose the marsh because she is mostly abandoned by her family. She has to live most of the time by herself. I wanted the story to be believable, and the marsh is a temperate climate so she could live, she didn’t have to worry about snow or freezing, and she had a shack. She could survive because you can truly walk around and pick up mussels and oysters. I know it’s not easy, but you can learn to do it. It was possible for her to survive in that environment. That’s the reason I chose it.”

Owens, who spent much of her life in the wilds of Africa, far from any other human, explained, “There’s a lot of me in Kya: girl, love of nature, live in the wilderness for years, feeling like I don’t belong anywhere. There’s a lot of me in Kya, but there’s a lot of Kya in all of us.”

She says that being totally alone changes a person. “When I was isolated in Africa all those years, I wanted to have social groups. I wanted to have more contact with people. But when I came back, I found out it’s not so easy just to do it. And that’s what happens to someone who’s isolated like Kya. She longed to be with people, but every time she had an opportunity she was shy and didn’t feel socially confident.

“One of the points of the book is that you do not have to live in a marsh to be lonely. A lot of people in cities are lonely. A lot of people in small towns, even though they have friends, are lonely because we don’t have the strong, long-lived groups that we used to have. And when we get away from that, not only do we feel less confident and lonely, but we also behave differently toward others.”

How does Owens make a story out of an isolated young woman who lives in a shack in the marsh?

“I came with the theme first. I wanted to write a story of a young girl growing up alone and how isolation would affect her, but I knew I couldn’t just write that story. It had to have a love story, and it’s a very intense love story. It’s a very compelling, I hope, murder mystery. Of course when Kya reached adolescence, she reached the time that she wanted to be with other people, she wanted to be loved. So she started in her way reaching out, at least watching, and there is sort of a love triangle that follows that is very intense.”

Will there be a movie? Crawdads gained the attention of actress Reese Witherspoon. Fox 2000 has acquired film rights and plans for Witherspoon to be the producer.

We can hope that the movie will be shot in North Carolina. But here the book’s problem jumps up. The geography described in the book, with palmettos and deep marshes adjoining ocean coves, seems to fit South Carolina or Georgia coastal landscapes better than North Carolina’s coastlands.

Nevertheless, whatever the moviemakers decide, North Carolinians can bask in the reflected glory of a No. 1 best-seller that claims our state for its setting. PS

D.G. Martin hosts North Carolina Bookwatch Sunday at 11 a.m. and Tuesday at 5 p.m. on UNC-TV. The program also airs on the North Carolina Channel Tuesday at 8 p.m. To View prior programs go to http://video.unctv.org/show/nc-bookwatch/episodes/