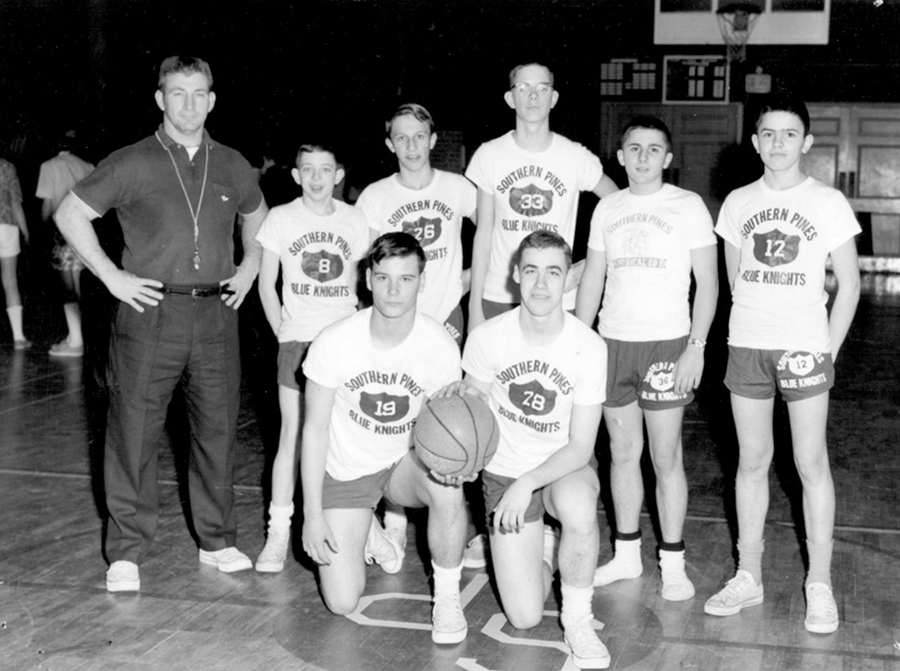

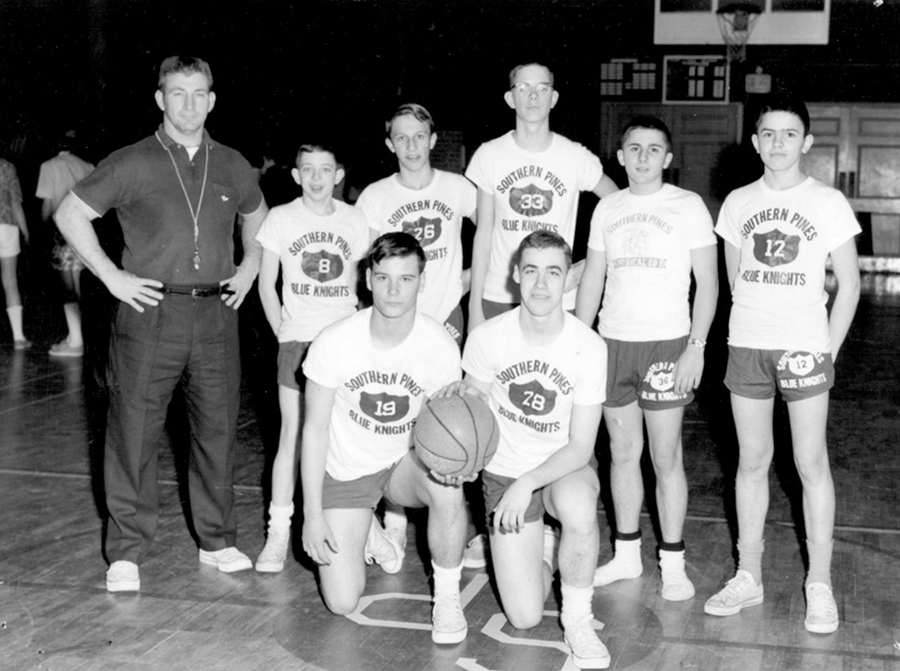

Coach

Remembering a man who made us better

By Bill Fields

John Wiley Williams, “Coach” to most, was a motion offense of a man, always on the move, as much shark as bulldog, although he certainly got the latter nickname for good reason. If he wasn’t jogging — at least 10 miles a day for a year when he was in his 40s, just to prove he could do it — he was cycling. If he wasn’t teaching someone the hook slide, he was demonstrating how to pole vault.

“It is better to wear out,” said one of the many slogans posted in Williams’ field house office at Pinecrest High School, “than to rust out.”

Coach, who seemed born with a whistle around his neck and a large ring of keys on his belt that jangled with every jumping jack, had bow legs and an odd gait. But few knew just how improbable it was that he could run and jump and make a drag bunt look like ballet.

Serving stateside in the U.S. Army during the Korean War, Williams was badly injured when a load of artillery shells fell on his legs. He spent a year in a Michigan hospital, had four knee operations and was informed by doctors upon his discharge from the service that he would never walk without crutches.

“They told Dad, ‘You’re never going to walk right again,’” says Dr. John Wiley Williams Jr., the oldest of John and Patricia Williams’ three sons. “But through rehab and work, he was able to recover.”

Star athletes who revered Williams, even as he ordered wind sprint upon wind sprint as the epilogue to a tough practice, didn’t know. Slacker boys in a Pinecrest physical education class, who would rather have been sneaking a cigarette than trailing Coach on a run through the woods to Midland Road and back, didn’t know. They didn’t know either — he didn’t know, until years after he boxed in the Golden Gloves and played high school football — he was born with one kidney.

“The only substitute for hard work is a miracle,” was another of Williams’ favorite aphorisms, and he came down squarely on the side of perspiration.

Williams was a fixture in the Sandhills for three decades — teacher, coach and athletic director — from his arrival in the summer of 1960 until his death at age 59 in a car-train accident the day before Thanksgiving in 1990.

“I don’t know how you judge things like this, but to me he was the most valuable citizen that we had in the county bar none,” says retired pediatrician Dr. David Bruton, 83, who became a close friend of Williams after opening his Southern Pines medical practice in 1966. “He was an extraordinary person, no doubt about that, devoted almost full time to others.”

Attending his 40th Pinecrest reunion two years ago, John Jr. encountered Tommy Grove, a fellow member of the Class of ’76 who had starred on the Patriot football and baseball teams. “Anyone who played for Dad, the typical response was how tough he was. They were bound by memories of how hard he worked them, that they survived Coach Williams,” John Jr. says. “Tommy came up and said, ‘I think of you as a brother, because your dad was like my father.’”

Plenty of Southern Pines residents saw Williams lining an athletic field, stripes as straight as the man pushing the chalk spreader. It was a smaller cadre of folks who knew he often lined up temporary shelter for young people who needed it.

“As a kid I had many, many roommates,” says Mike Williams, the middle son. “They might have an alcoholic parent, they might be getting beat up — they became my brother. It wasn’t an everyday occurrence, but when the need arose, my parents opened their home to anyone.”

And not just their home, as Joe Robinson, Pinecrest Class of ’71, discovered when he returned to the Sandhills to teach and coach after graduating from N.C. State.

“I was renting a little efficiency at the Pinehurst Motel down on the highway,” says Robinson. “Two beds and a kitchenette. One night about 10 o’clock, a kid knocked on the door and said, ‘Coach Williams told me I could stay with you for a little while.’ A ‘little while’ turned out to be three months. Everybody thought he was a hard man, but in a lot of ways he really wasn’t.”

He was, in Bruton’s memory, a “consummate con man” that swept up other members of the community to lend a helping hand, whether for new bleachers at the ball field or a new beginning for boy who deserved it.

“He would farm out the kids to us and other families if he got more than he could handle,” Bruton says. “He’d tell you an awful story that you had to get up the money to take care of it. He sent a lot of kids to school, to camp, whose parents couldn’t afford it. It was probably the best money I’ve ever spent. He was an unusual fellow — he didn’t seem to care much about John Williams, but he sure cared about others.”

Coach was born on Jan. 29, 1931, in Lenoir County, the middle child of Walter Spencer Williams, a successful Kinston businessman, and Marjorie Earnhardt Williams. Marjorie died shortly after giving birth to her third child. Less than a month later Walter took Williams, not yet 2 years old, and his two sisters (Lib and Billie) across the state to Cabarrus County to be raised by Marjorie’s parents, John and Willie Irene Earnhardt, Lutheran farmers (and relatives of future stock-car legend Dale Earnhardt) trying to eke out an existence in hard times.

Walter Williams remarried quickly, to a friend of Marjorie’s, and had little contact with his three children. His son — born Jackie Arnie but renamed John Wiley by his grandparents when he was baptized — grew up loved but with few material possessions. “John slept in a crib until he was 6 years old,” Patricia Williams wrote in an unpublished memoir. “He told me he remembered his feet sticking out at the end of the crib before he got a real bed.”

By the time he was sleeping in that bed, Williams was already contributing to the family effort, “Pop” Earnhardt having fashioned a diminutive plow so his grandson could work the fields. “He’d be at the field at the crack of dawn from the time he was 5 or 6,” says John Jr., “and once he was in high school he worked on a loading platform, throwing heavy things on the train. That’s how he got strong, from working.”

At Mount Pleasant High School, Williams was a talented athlete but struggled in the classroom because reading was difficult. His wife, a longtime elementary school teacher, believes it was because he was dyslexic. High school might have been a miserable experience for Williams if not for the guiding hand of Mount Pleasant teacher/coach Luther Adams. Raised in an orphanage, Adams saw potential in the gritty student who, Patricia wrote, “had the heart and desire to excel in sports” but was growing up in a household whose priority was its crops.

Adams moved to Southern Pines as school superintendent in 1959. A year later, when a larger student body gave Adams the authority to expand the faculty, he hired the young man for whom he had been an instrumental mentor a decade earlier. After graduating from Atlantic Christian College, Williams had been at Pineland College in Sampson County for two years when he was hired as physical education teacher at East Southern Pines Elementary, becoming an assistant coach for several Blue Knight teams as well. Three years later he established a track and field team, the first in Moore County, and began to become an integral part of the town using sports to build community bonds.

“John saw the difference [Adams] made in his life,” Patricia wrote, “and he set out to pattern his life’s work after his role model. He wanted to coach, to help young people, to do special things for poor people, and to be a good father and husband. He did all that and more.”

A religious man who carried a Bible and could quote it, Williams wasn’t a saint. He was well known to local law enforcement for a habit of driving too fast. It was in his blood — after all, he was a cousin of the racing Earnhardts of stock car legend.

“He couldn’t not speed,” says Gary Barbee, Pinecrest Class of ’75, a four-year pitcher on Williams’ baseball squad. “Sometimes the police would let him go, but still he got a lot of tickets. His wife gave him a spool of thread to screw into the floorboard below the gas pedal on his old Studebaker so it wouldn’t go above 55 miles an hour. That was the only way to keep him from getting any more tickets and having their insurance go up any higher.”

“Might be true,” Mike Williams says. “He did not like to go slow. If we were going to the beach with a group of folks in several cars and we stopped to have a soda, it was very rare that somebody didn’t ask him to slow down because they couldn’t keep up.”

Driving to away track meets in Southern Pines’ aging and slow activity bus, the “Blue Goose,” Williams would navigate winding back roads to shave time and beat other schools to the venue. “Getting there first was an event to him,” Mike says. “That was pretty competitive.”

Keeping up with Williams when he wasn’t behind the wheel was difficult enough. As a young football coach, he liked to have players tackle him rather than dummy runners — breaking four watches in one season. “He lived up to his ‘Bulldog’ nickname fighting for rebounds or diving for a loose ball in a pickup basketball game,” says Robinson.

Mike Williams remembers trips when he and his older brother would be in the back seat, squabbling the way siblings do. “Mom would have had enough,” Mike says, “and he would just reach around with his right arm and the next thing you know we’re elevated off the seat while he continued to drive down the road. He was very calm as he asked if we were ready to settle our differences.”

Coach would roughhouse with his baseball players and always came out on top. “We’d jump on him, two or three of us, trying to wrestle him to the ground and you just couldn’t hold him,” Barbee says. “He’d bite, kick, whatever it took. Someone was adjusting our old pitching machine once. He was in the batter’s box and a ball hit him in the back of the head. It would have knocked you or me out. He just rubbed his head a little bit and kept going. He was a tough cookie, man.”

And he sought to make his players tough. Barbee’s lungs still burn recalling “Burma Road,” a practice drill. “You’d run to first and back, then to first and second and back, then to first, second and third and back. Finally, to first, second, third and home. Then the next time, you did each sprint twice. And after every game, home or away, win or lose, we ran 10-to-15 100-yard wind sprints. Opposing teams would say, ‘Y’all, we need to cut the lights off.’ It didn’t matter. We ran. We were in shape.”

Williams’ own running — he built up his muscles with leg lifts, but his limbs still ached constantly — became part of Coach lore. As a sentence for a speeding violation, a judge in Southern Pines offered an option of paying a fine or walking to Howard Johnson’s on U.S. 1 in Aberdeen, round trip of about 4 miles. That was easy pickings for Coach, who would run there and back in less time than it took to watch an episode of The Andy Griffith Show.

The feat that caused the most stir was a hot and humid day in the mid-1970s when Williams ran home to Southern Pines from Raeford, the best part of marathon distance. Mike watered him down with a garden hose in the backyard while his wife phoned David Bruton to ask him what she should do for her exhausted husband. “Quick,” Bruton said, laughing, “go grab him before he runs to Raleigh.”

One of the best runners to graduate from Pinecrest, Jef Moody, a middle-distance star who was poised to make the 1980 U.S. Olympic team before the Moscow boycott, spent more than a year of Saturday mornings as an eighth-grader logging miles with Coach. The experience normalized what had been a jarring move from Philadelphia to a still-segregated South as an African-American fifth-grader in the spring of 1968.

“He asked me if I wanted to come run with him on Saturdays at Mid Pines,” says Moody, 61, who now coaches the men’s and women’s track and cross country teams at Sandhills Community College. “We’d run the 18 holes, just the two of us, then I’d run home. It really meant a lot to me. I never had him for a P.E. teacher or a track coach, but he was my buddy.”

When Robinson was back in his hometown as fledgling teacher and coach, Williams gave him some advice about his new students. “You’ve got to love every one of them,” Coach told him.

Williams’ support for his athletes, present and past, was resolute.

Coach finagled funds from Bruton and other townspeople so he could buy an early whirlpool bath — which looked like a metal washtub with a small boat propeller — so young pitchers could soak their throwing arms. “He could con me and others out of whatever he needed for his sports activities,” Bruton says. “That tub cost more than it was worth, of course. But he was very proud.”

Once I pulled a back muscle at a Little League practice that Coach was overseeing.

“We’ll go get you in the tub,” he said, “and get some Cream of Jesus on it.”

At least that’s what it sounded like he said. Sometimes Coach’s sentences, voiced in his husky Tar Heel accent, were like a hiking trail that didn’t quite make it to the summit. When we got to the high school field house, I noticed an industrial-size container of orange goo.

He had been talking about Cramergesic, a therapeutic muscle balm that made Vick’s vapor rub seem as mild as a peppermint. But it helped my back.

That was the side of Coach who would gently catch a wasp between thumb and index finger and deposit the insect out a car window instead of swatting it dead, perhaps the day after he’d set his watch back twice so a jayvee football practice would finish at “six bells” an hour after weary players had heard a half-dozen chimes waft to Memorial Field from the Episcopal church.

“I was always challenged getting rides,” says Tim Maples, a senior star pitcher on Williams’ 1979 state championship Pinecrest baseball squad. “It seemed that I was always spending time with him. ‘Where you going to be, Maples? I’ll pick you up.’ I’d be at home, or at the Elks Club pool, and he’d pick me up in the bus, and he’d take me home in the bus after practice.”

Coach — the generous spirit and the drill sergeant both — stuck with people long after they’d left his class or his gridiron. His boys carried the connection and attitudes to college campuses, pro ball and war.

“He walked the walk,” says Maples. “He’d talk a lot of times about intestinal fortitude, heart, 110 percent. It was like he had invented those terms.”

Those who became educators themselves brought Coach’s ethos to their lives. “The one big thing he did was mentor others to become leaders and grow community involvement,” says youngest son Mark Williams. “For me, it is this handing down of a sense of responsibility, ethics, knowledge, sportsmanship and values that continues and is so powerful.”

One of Williams’ disciples, Bill Strickland, took his lessons to the Vietnam War, where he was terribly injured. “He told me he could remember waking up, after several days, having gone through surgeries,” says Mike Williams. “He was in a bed, flipped upside down so he couldn’t move. He said, ‘Mike, I woke up and my doctor was laying underneath.’ He said, ‘Soldier, you should be dead. You should not be here. What force has kept you alive?’ And Billy said, ‘Coach Williams.’”

By the fall semester of 1990, Williams had passed on his coaching duties to others and was teaching and serving as athletic director at Pinecrest. On Nov. 21, the day before Thanksgiving, he had an early morning dental cleaning appointment, then ran an errand to McDonald Brothers Inc., a building and lumber supply company north of Southern Pines.

John and Patricia, who had moved to Whispering Pines, were looking forward to a family gathering — sons, daughters-in-law and grandchildren. He went to the store to buy chains to complete a swing set he was building for the youngest members of the family. As he drove across a railroad crossing, his sedan was hit on the passenger side by an Amtrak passenger train, the Silver Star, which had just left Southern Pines on its journey from Miami to New York.

“I don’t think anybody knows exactly what happened,” says John Jr. “My theory is that they had a new puppy and he had that new puppy with him. I bet either the puppy distracted him or it got down into the footwell where the pedals are, and he couldn’t make things work.”

The long holiday weekend was transformed into a period of grieving across the Sandhills. “It was such a shock,” says Nat Carter, 78, Williams’ longtime teaching and coaching colleague in Moore County. “It was hard to figure what happened with the train. We lost a great one when we lost him. You could learn a lot just watching Coach John and being in his presence.”

Pinecrest sports teams compete at the John W. Williams Athletic Complex, facilities that honor his longtime contributions. Those who knew Coach are in middle age or beyond, their memories aging but vivid.

“We always said the Lord’s Prayer before a game,” Maples says, remembering his Pinecrest baseball days. “We put in our hands, in the dugout. Coach’s hand was always down first, and I always tried to get my hand on top of his.”

When the Patriots were at bat, Williams jogged to the third base box. Everybody took the first pitch, sometimes two. Tug of the cap, touch of the face, swipe of the chest, rub of the arm. You didn’t want to be the player who blew a sign.

“I missed a suicide squeeze at Laurinburg and about killed a guy,” Barbee says. “He was running on the pitch and I took a cut. Coach would get right in your face and just chew you out. He wouldn’t put up with anything. But we all trusted him and believed in him.”

The feeling was mutual. PS