Rose Cottage

James Tufts’ first foray into vacation homebuilding, once again a showplace

By Deborah Salomon • Photographs by John Gessner

A rose is a rose is a rose . . .

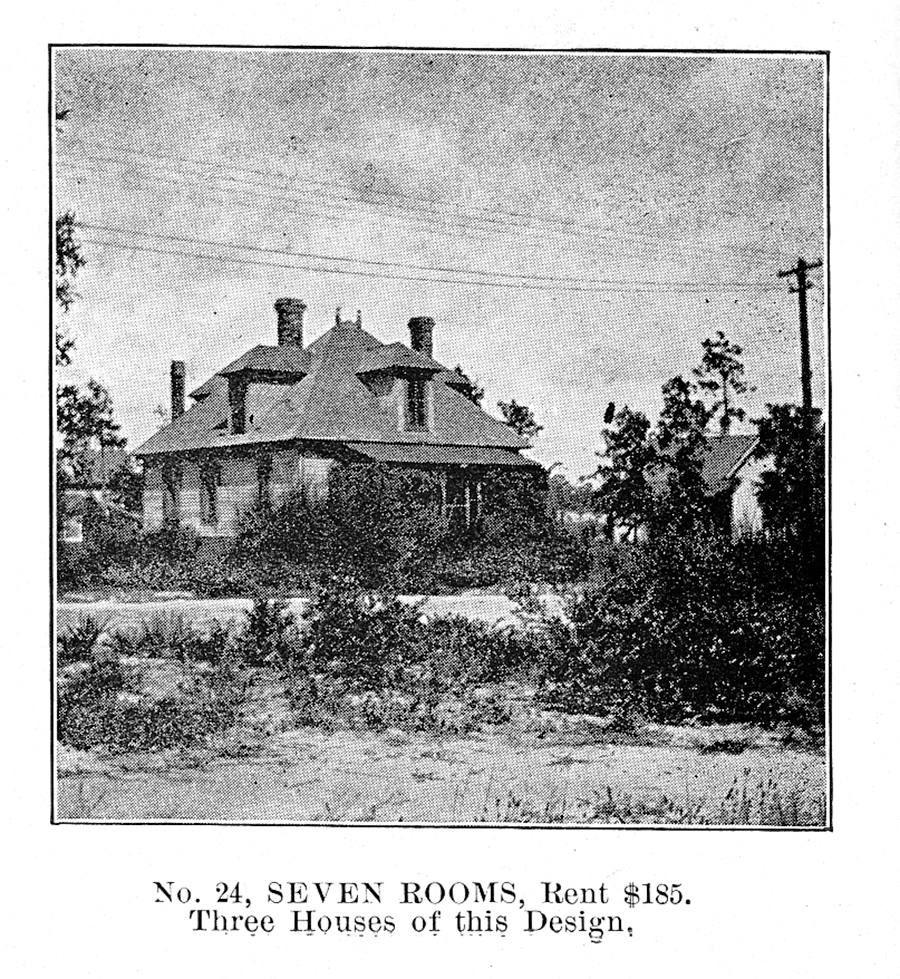

However, Rose Cottage looks and lives very differently than when it was built by James Tufts in 1895 — among the first of about a dozen. This house, intended as a rental, then sold in 1905 for $1,050, had few neighbors and a clear view to the Carolina Hotel and nascent Pinehurst village. Its tight floor plan, consisting of seven rooms, a small sun porch, and one bathroom, begged expansion accomplished by subsequent owners over the next three decades, culminating, circa 1940, with the colorful Razook family. F.R. Razook, a Lebanese immigrant, and his wife Rose had established a haute couture ladies’ boutique in Blowing Rock, N.C. They followed the money to Pinehurst, Palm Beach, Manhattan and Greenwich. While the Great Depression wiped out some clientele Razook’s thrived on survivors. Gen. George Marshall’s wife (with a home in Pinehurst) reportedly purchased the gown she wore to Queen Elizabeth II’s coronation from Mme. Razook.

However, by the 1960s, this rose had faded. The younger Razooks came down for holidays only. Modernization stalled after 1940. Gorgeous heart pine floors slumbered beneath ratty broadloom. Critters overran the attic. The layout had been chopped into a warren of small rooms of indefinite purpose. The kitchen was a period piece and the bathrooms . . .

***

Lisa and Bill Case — retired lawyers who married in 2008 — weren’t looking to rebirth a landmark. They knew what such projects entailed after living in the German Village section of Columbus, Ohio, a revitalized neighborhood on the National Register of Historic Places. Bill first visited Pinehurst with his father, on a business trip in 1964. He brought Lisa, a new golfer, with increasing frequency, telling her during a Thanksgiving jaunt, “You have to play No. 2.”

Slowly, as retirement took shape, Pinehurst looked promising — not only for golf. “We were footloose, could go anywhere, but we kept coming back here,” Lisa says. They liked the climate and population potpourri. However, this time Lisa wanted a sleek modern residence, “No curlicues, easy to keep clean.” A Realtor gave them the tour; they passed Rose Cottage without going inside. Yet the charm of the old place caused them to ask for a walk-through.

They returned to discover the house a mess, old and tired from not being occupied. But quality materials, location and antiquity left an impression.

“Bill’s eyes were like saucers,” Lisa recalls.

Options were discussed and decisions were made during the 8-hour drive back to Columbus.

“As long as you give me rooms for guests and a kitchen that I love . . . ” Lisa said, having recently remodeled hers. “We could see ourselves living here.”

They took the leap in 2013 with a lowball offer. Their Columbus house sold in a day. Down they came with one dog and two cats, hired a designer and builder, rented a condo for the duration.

Bill: “I thought we’d gut the bathrooms and kitchen and do the rest later,” which, as it happened, was like being a little bit pregnant. Their builder wisely advised a “one fell swoop” plan, to avoid tearing the place apart twice.

And tear it apart they did, moving interior walls, combining cubbies, creating spacious bathrooms and storage, opening up the staircase with a transom and handsome banisters all without altering the footprint.

***

The result begs questions, reveals surprises. What purpose, the room just inside the front door? Larger than a foyer — likely a parlor before the enormous solarium was added. To the immediate left, the dining room with an off-center fireplace could have been a ground floor bedroom for grandma, as was common in houses of that era; formal dining rooms weren’t required since the first Pinehurst cottagers ate communally. Windows at the end of the dining room suggest a small sun porch. Ceiling beams, now painted white, could be original or an addition. Then, in a bay window area connecting dining room to kitchen, the Cases created a conversation nook/butler’s pantry/bar.

As stipulated, much attention went into Lisa’s kitchen. “We splurged on the soapstone counters,” she admits. They are black, the walls throughout a soft, soothing grey, the cabinets white. Color pop comes from her unusual red gas range and dishes in a variety of bright primaries. French doors open onto a brick patio, which they added.

The real main floor knockout, however, is that 30×20 foot solarium, a veritable fishbowl with three complete window walls not covered by shutters, shades or drapes. Here, the Razooks held high society soirees. Now, Bill’s stringed bass fills a corner, silent but decorative.

“People look in . . . we wave to them,” Lisa says.

Upstairs a narrow hallway, sloping from age, leads to three bedrooms with niches and windows set low on the mansard walls, creating a treehouse effect. Nobody knows why the Juliet balcony off the master bedroom lacks a door. Obviously, it wasn’t planned for sitting. “We crawl out the window and decorate it for Christmas and July 4th,” Lisa says.

Ever the conservationists, Bill and Lisa created sliding pantry doors from original hinged, moved the porcelain kitchen sink into the laundry room, made free-standing cabinets from removed built-ins and salvaged old knobs for pegs. Since no clawfoot bathtub survived, Lisa chose a reproduction.

Because all but one room is moderately sized, the house doesn’t feel like 3000 square feet, “But we use every inch,” Lisa says.

Across the garden, a former carriage house/garage has become Bill’s man cave, repository of baseballs and books, where he researches and writes. Bill appreciates history and its icons: he owns a mint-condition 1954 Mercury used in the Johnny Cash film bio Walk the Line. A Waring blender with glass canister has been converted to a lamp. And on the walls hang a continuation of golf course art, both paintings and photos, appearing throughout Rose Cottage. “We marshaled at St. Andrews in 2015,” Lisa says proudly. Other wall décor includes their “happy place” beach in Scotland, archival photos and documents relating to Rose Cottage, personal mementos, and a Columbus landmark — the Wonder Bread factory sign.

The couple’s furnishings — his, hers and theirs — stretch the eclectic concept. An heirloom sideboard looms over the dining room like a frigate. A round English-manor hall table centers that mysterious front parlor. On the mantel stands a trophy dated 1941, won by Bill’s mother at the (prophetically) National Rose Show. Lisa found fertile hunting grounds in Moore County consignment shops — everything from an ornate French chateau desk reproduction and carved settee to tables and chairs with contemporary Scandinavian lines. When pushed to feature a color, as in the master bedroom, Lisa chose “cat’s eye” green, a pale avocado evocative of bygone days.

“Doing the outside is my next project,” says Lisa, who completed a Master Gardeners’ course. As yet, neat plantings neither overwhelm nor detract from the house itself. Lisa is learning what grows well in this warmer climate. “I’m thinking about a pollinator garden, but so far, it’s a work in progress.”

All in all, Lisa and Bill have adapted the prototype Pinehurst cottage to active retiree living: original wide baseboards and doorframes meet recessed lighting. Long halls become gallery space. The black-and-white magazine kitchen co-exists with a Welsh cupboard. An exterior painted the white and money-green, popular mid-20th century, gives no hint of what lies within.

Bill and Lisa are pleased. “We’ve learned ‘porching’ . . . sitting outside with a bourbon at four in the afternoon, watching the world go by,” says Lisa. “Our neighbors are wonderful. This house has good vibes.”

With one ghostly exception: “I was lying in bed and Bill was watching TV. I swear I heard somebody standing by the bed. She whispered, ‘This is my house.’”

To which Lisa rightfully replied, “Oh no, this is MY house now.”