Defying Mob Rule

Finding justice in the Jim Crow South

By Stephen E. Smith

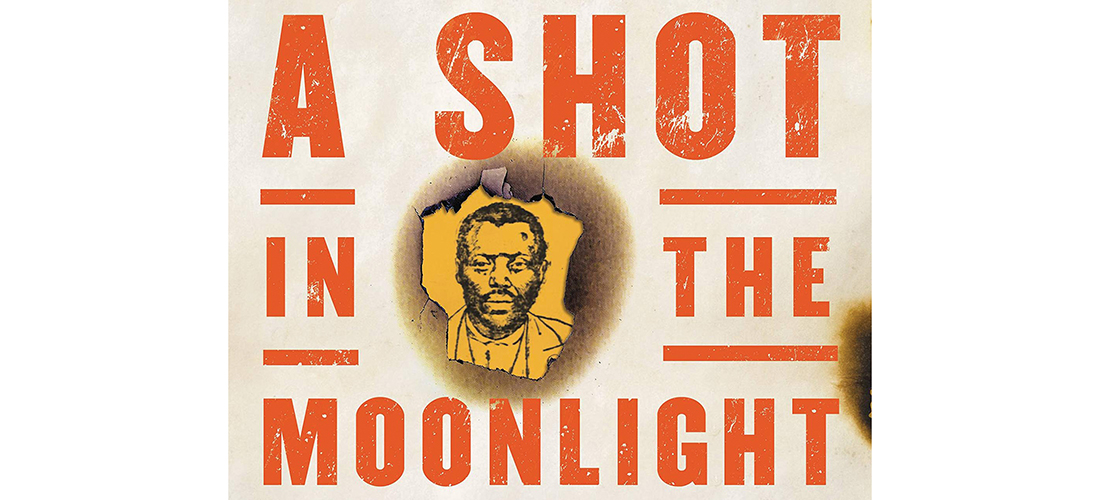

Ben Montgomery’s A Shot in the Moonlight is a timely retelling of an anomalous story of a former slave who, with the assistance of a Confederate war hero, faced down the forces of white supremacy in the Jim Crow South.

On a moonlit night in January 1897 in Price’s Mill, Kentucky, two dozen “Whitecappers,” self-styled Ku Kluxers, gathered in front of the farmhouse of an innocent 42-year-old former slave, George Dinning, where he slept with his wife and their seven children, and demanded that he submit to the mob’s intent, whatever it might be. Armed with pistols and shotguns, they accused him of theft and ordered him from the relative safety of his home, stating he had just hours to abandon the 125-acre farm he’d worked years to purchase from his former owner and to move himself and his family far away from Price’s Mill. When Dinning denied the accusations of theft and refused to step outside, the mob betrayed their intentions by firing blindly into the cabin, wounding him in the arm and head. Dinning grabbed his shotgun, climbed to the second story of the house and got off a single blast in the moonlight. The shot, although imprecisely aimed, killed 32-year-old Jodie Conn, a member of a wealthy planter family. Then Dinning fled for his life, making good his escape clad only in his nightclothes. The mob dispersed, but vigilantes returned to the Dinning farm the next day, displacing the family and burning the house and outbuildings.

Had it not been for Dinning’s desperate act of self-defense and his subsequent escape, his brief encounter with the mob may well have resulted in just another lynching — there had been at least 13 in Kentucky in the preceding year — but the moonlight assault at Price’s Mill turned out to be the exception to the rule. Dinning sought justice through the courts, an almost foolhardy act of audacity in the Jim Crow South. The day following his escape, he surrendered to the sheriff of an adjoining county, who took him into protective custody and moved him to Bowling Green, where he would be safe, at least for a while. When Dinning was transported back to Simpson County for trial, it appeared he might again fall victim to mob violence, but Gov. William Bradley, a Republican, ordered two companies of soldiers to guard the accused, a politically unpopular action that saved Dinning’s life.

Trial was held before an all-white jury (Montgomery reproduces much of the transcript verbatim), and astonishingly, Dinning was found not guilty of murder but guilty of manslaughter. He was sentenced to seven years in prison. Even so, there was the possibility he might be lynched before being transported to the state penitentiary. In 1892, 161 Blacks were lynched in the country, and only in cases where Blacks took up arms to protect defendants, most notably in Florida and Kentucky, did intended victims escape mob rule. But Dinning had acted in self-defense and to protect his home and family, engendering widespread support, even among the white community, and within a few weeks he was pardoned by the governor.

But the story doesn’t conclude with Dinning’s pardon. He sued his attackers by taking advantage of a legal irregularity meant to quell racial unrest: “ . . . so long as the courts offered the veneer of impartiality,” Montgomery writes, “and Black plaintiffs could access the civil courts to seek justice, they might not revolt or boycott or march or protest other areas of discrimination.” Nevertheless, Dinning’s civil action introduced him to attorney Bennett Young, a well-known lawyer in Louisville, a hero of the Confederacy, a true son of the South who fundraised for Confederate monuments and belonged to veterans’ organizations but who had also founded the Colored Orphans’ Home Society and frequently defended people of color who had been falsely accused of crimes.

The Dinning/Young legal alliance is and was a social aberration, one whose circumstances do not fit neatly into the American story, past or present. How Young managed to rationalize his divergent points of view remains unclear, but Montgomery speculates his benevolence was “coupled with white supremacy, the notion that a certain kind of power came from kindness.” Whatever his motivation, Young fought long and hard on Dinning’s behalf, and at the conclusion of initial civil action, the jury found for the plaintiff. The unlikely lawsuit — a Black man suing his white tormentors — was a success, the first of its kind in the country. The judge dismissed a few of the defendants, but the remainder were assessed $50,000 in damages, $8,333.33 each, an astronomical sum at the time.

Newspapers heaped praise on the judge and jury: “Whatever may be done with the judgment of $50,000, this verdict by a white jury serves notice that mob law is declining in popular favor in Kentucky, and that the State’s standards of procedure are rising,” wrote the Washington Star. “The leaven is in the lump, and it is working” — which, of course, it was not.

As expected, several of the defendants claimed they were unable to pay damages — “no property found” was reported to the court — but Dinning continued suing them, extracting what little money he could and tormenting the principals until they were in the grave.

Certainly, Dinning’s story of salvation and retribution is worth noting, but so are the stories of the approximately 4,400 victims who did not escape mob rule. They are acknowledged now in The National Memorial for Peace and Justice, and the publication of Shot in the Moonlight is likely, at least in part, a response to recent racial justice demonstrations and the worldwide outrage to the tragic death of George Floyd and other Black Americans who have died under questionable circumstances.

Montgomery claims he scrutinized the historical record and reported Dinning’s story accurately and impartially. “I have made just a few of the very safest assumptions,” he writes, “in the service of the story.” But in his introduction, dated 2020, he acknowledges recent examples of white supremacy and racial injustice. He’s emphatic: “The problem with the Confederate flag and the granite statues of dead soldiers is that the Civil War never ended. It developed into skirmishes and entanglements. As Nikole Hannah-Jones has written, it morphed into looser, legal forms of enslavement that are just as damaging as the whip. It rages on Facebook and in classrooms and in the streets of American cities, still.” PS

Stephen E. Smith is a retired professor and the author of seven books of poetry and prose. He’s the recipient of the Poetry Northwest Young Poet’s Prize, the Zoe Kincaid Brockman Prize for poetry and four North Carolina Press awards.