On the field, on the court, in life

By Bill Fields

Charles Waddell was only in elementary school, but he wanted to do things the right way. He wanted to stand out.

He and his older brother, Frank, tagged along with their father, also named Frank, as he took care of his early morning janitorial duties at The Citizens Bank and Trust Company on Broad Street in Southern Pines, where he had a part-time job in addition to a full-time maintenance position at Carolina Power and Light.

After helping empty trash cans and other light chores, Charles would sit down to do his homework. “He would write it out in pencil,” Frank recalls, “and while my dad and I would continue cleaning, he would use one of the typewriters in the bank and try to type it out.”

Sometimes brother Frank, nearly eight years older, who had taken a year of typing, would take over and finish because the family had to go home and eat breakfast before the boys went to school. “He always had an interest in everything,” Frank says. “You knew he would be a good student, and he certainly developed into a fine athlete.”

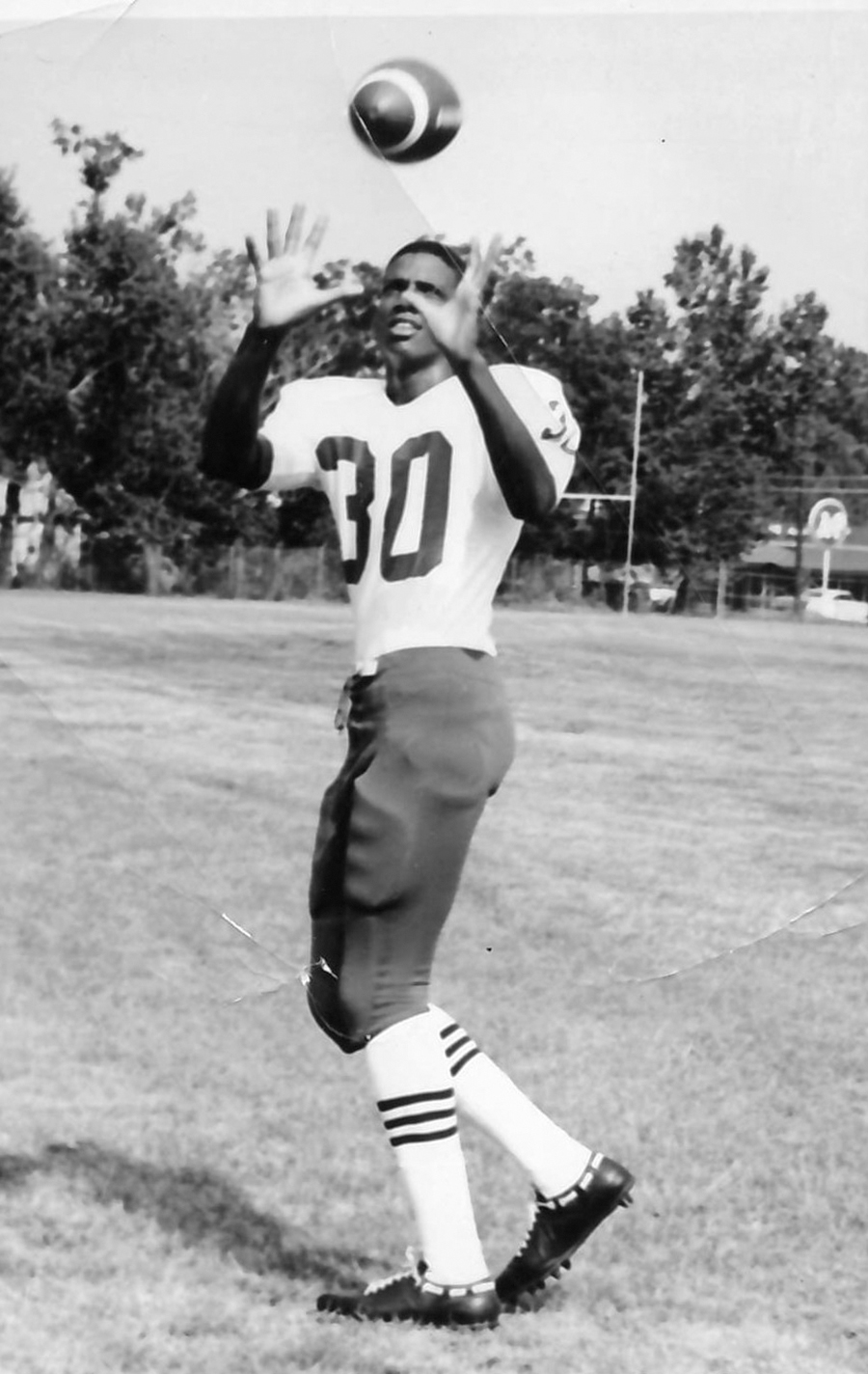

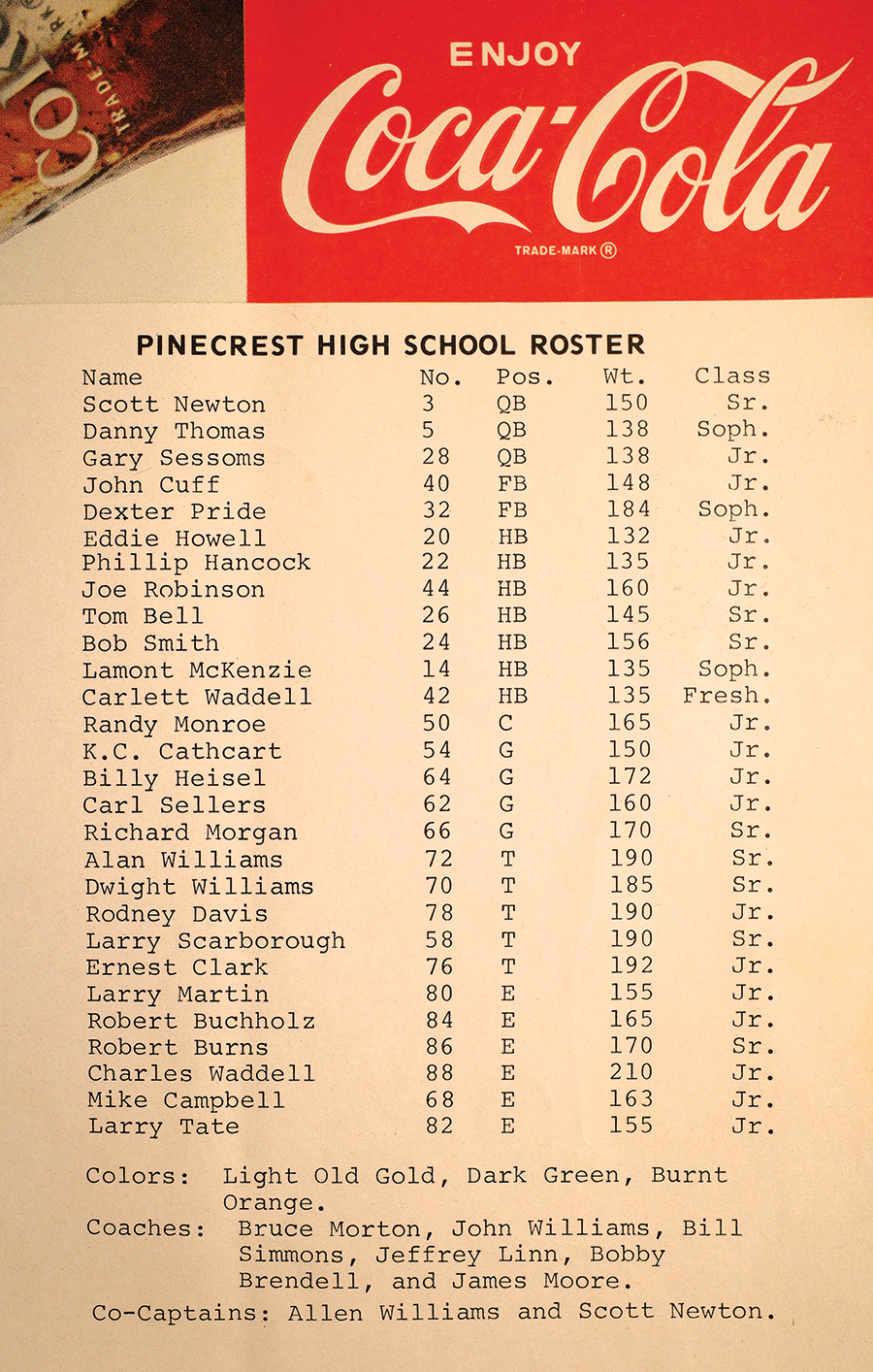

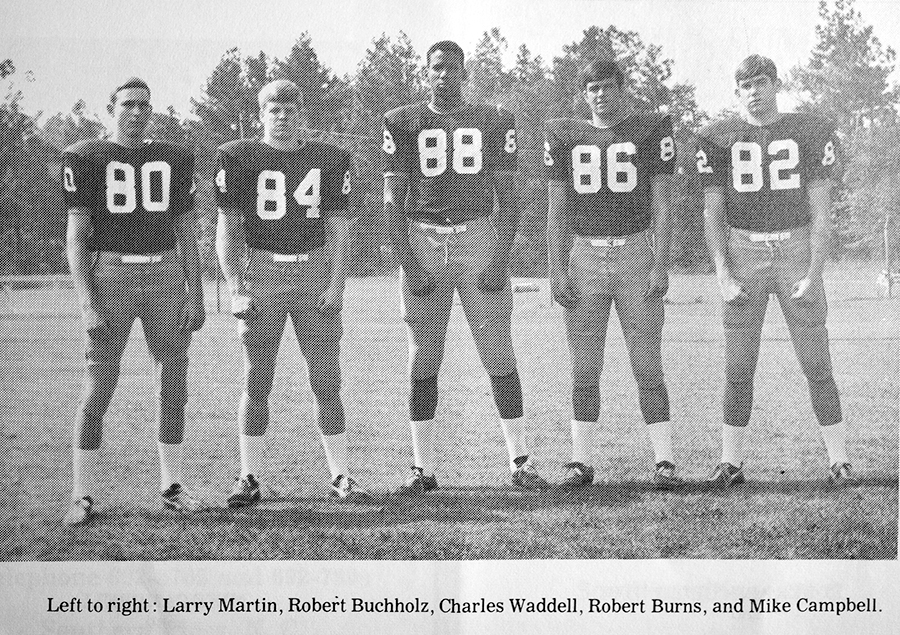

Fifty years ago, Charles Waddell graduated from Pinecrest High School, where he was all-state in football and basketball and excelled in the shot put, finishing second in the state in 1971. When, in 2013, the North Carolina High School Athletic Association named the top 100 male athletes in its century of existence, Waddell made the list. He led the Patriots to a state 3-A basketball title. Two of his fellow all-state hoops stars? Durham’s John Lucas and Shelby’s David Thompson, who would go on to star for Maryland and N.C. State, respectively.

“In the East-West All-Star basketball game, on one play I was bent down just a little bit and he came flying by and I was looking at the bottom of his shoe,” Waddell says. “Thompson was unreal.”

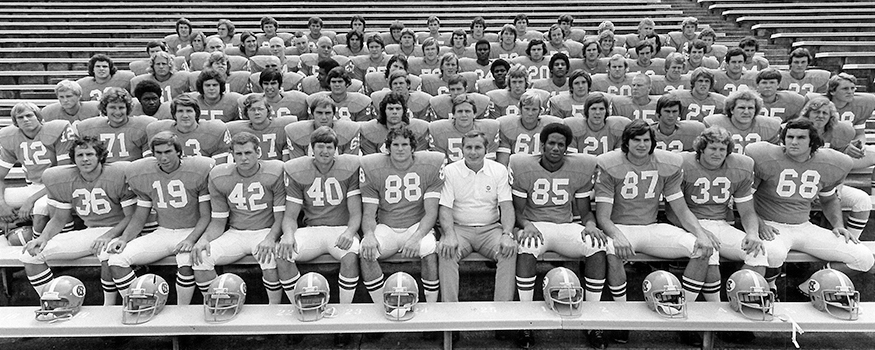

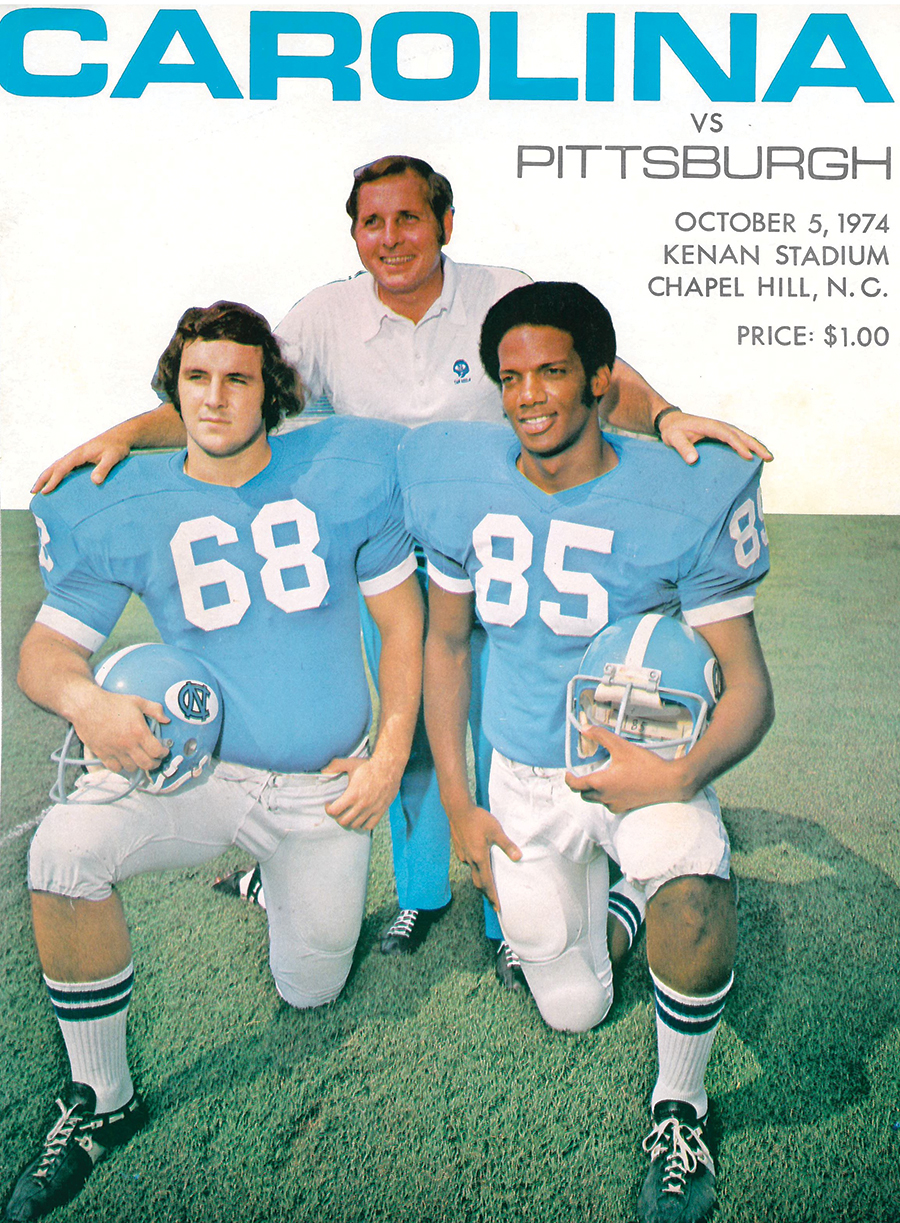

Waddell’s prep experiences were a prelude to further success in college. He earned a football scholarship to play for coach Bill Dooley at North Carolina. While in Chapel Hill, he also played two seasons for Dean Smith’s basketball Tar Heels and was a member of the UNC track and field team. He was the university’s first athlete to letter in more than two sports since Albert Long Jr. (track, football, basketball, baseball) in the 1950s. Although there have been about a dozen dual-sport Carolina lettermen since Waddell graduated, he is the last to letter in three sports (receiving three letters in football, two in basketball and one in track). The versatility led to him receiving the Patterson Medal, UNC’s highest athletic honor as a senior in 1975, joining a distinguished roster of recipients including Vic Seixas, Charlie Justice, Lennie Rosenbluth, Larry Miller, Charlie Scott, Don McCauley and Tony Waldrop.

“He was just always trying to succeed, and he had the skill set,” says Craig Gordon, Waddell’s best friend since they were 4 years old in West Southern Pines. “He could compete in just about anything. He didn’t run very fast, but he was quick for a big guy. We were tracking together until seventh or eighth grade, then he started stretching out. He went on and did some great things. But Charles tried to be the best he could be from a young age.”

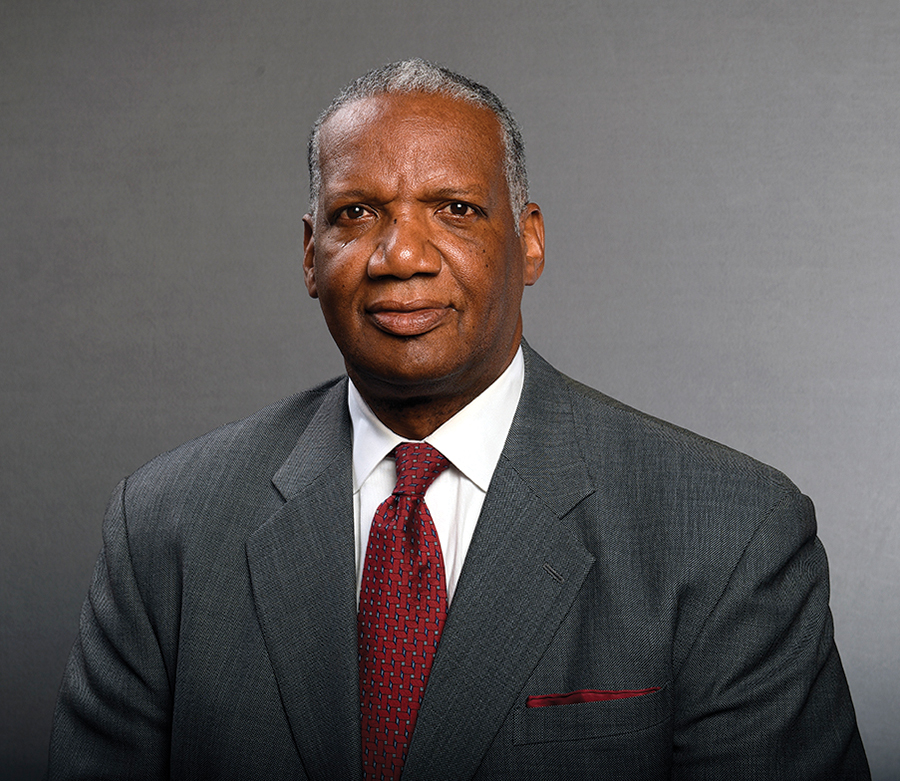

Waddell is 68 now, special assistant to the athletics director at the University of South Carolina, where he has held various posts in the athletic department since 2006. “I’ve been down here a long time, longer than I anticipated,” he says of being a Tar Heel in Gamecock country. “But I’ve gotten to develop some pretty good relationships with folks, the student-athletes and people I’ve worked with at the university.”

He ended up in Columbia with his wife, Sandra, and their three children (Christa, Cassandra and Cortez) after earlier positions in business and college athletics following a four-year, injury-hampered stint (neck, knee, shoulder) as an NFL tight end with the San Diego Chargers, Seattle Seahawks and Tampa Bay Buccaneers.

“It was really disappointing because I was on injured reserve three of the four years,” says Waddell. “You start getting hurt . . . I tell kids now that you really are a commodity in pro sports. If you have a car that breaks down on you three out of four years, you tend to get rid of it because there’s a new model coming out every season. I love the game, but it does take its toll. I’m reminded of those days just about every morning when I get out of bed.”

Frank was an early role model for Charles. He was on the West Southern Pines High School state championship basketball team as a freshman in 1959 and when the Yellow Jackets were runner-up in the state his senior season of 1962. “My brother was a really good athlete,” Waddell says. “I would say he was my first coach. He taught me just about everything. And he played on a state championship team and a state runner-up team in basketball just like I did.”

Both were kept on track by the guidance of their parents. Frank and Emma Waddell didn’t tolerate mediocrity in the classroom or any foolishness outside of it.

“Charles was always very studious, and his mom made sure every day the priority was school,” Gordon says. “His parents were very straight-shooting folks — everybody in the community pretty much was that way and looked after one another. If I did something, my mother would know about it before I got home.”

At a time when Blacks weren’t allowed to play organized youth baseball in town, Emma Waddell created uniforms and formed a team for Charles and his friends in their neighborhood. “Our mother was instrumental in forming the ‘Honey Bees,’” Frank says. “They didn’t really have anybody to play — I think they went to Raeford once — but she made sure they had a team.”

Waddell looked up to Charlie Scott, the first Black basketball player at North Carolina, and a certain Boston Celtics center. “Bill Russell has always been my idol,” Waddell told the News and Observer when he was a teenager. “I’ve always admired the way he wanted to win. He was never satisfied with being second.”

West Southern Pines High didn’t have the resources to field a football team, so Waddell made the tough decision as a sophomore to attend East Southern Pines in 1968-69 prior to the consolidated Pinecrest campus opening in the fall of ’69. He played football and basketball for the Blue Knights. For the first time the predominantly white school agreed to schedule a game with the Yellow Jackets, who for years had wanted the chance to square off against the East side team. With Waddell, already 6-foot-3 and 210 pounds and a force down low, the Blue Knights won the game. He would go on to average 25 points and 15 rebounds as a high school upperclassman.

“It was a little painful to go to the East side, and that basketball game was a tough one because West Southern Pines had a rich basketball history and had wanted a game with East Southern Pines for a long time,” Waddell says. “But I think it was the right thing for me to do. I was able to acclimate to the integrated situation a year before Pinecrest opened. And high school football helped with integration, because that was one of the first things that brought people together.”

As a senior, Waddell led the Patriots to a 7-2-1 record in the fall of 1970, which remained the school’s best football season until 2009. He went to Carolina on a football grant but with an understanding that he could try to play basketball too. His first year in Chapel Hill was the last year that freshmen could not play varsity football and basketball. The youngest Tar Heels, including Waddell, who stood 6-5 and weighed more than 220 pounds, still practiced with the main team.

“I got matched up with Charles quite a bit in practice,” says John Bunting, a senior All-Atlantic Coast Conference linebacker in ’71 who was the Tar Heel head coach in the 2000s. “He was a freshman going against a senior, but he was not intimidated, and he was very strong and athletic for a true freshman.”

Ted Elkins was a defensive end from Charlotte who arrived on campus with Waddell and, like Bunting, went up against him in practice. “It seemed I was always paired against Charles,” Elkins says. “He was a big guy and a great athlete. He wasn’t real demonstrative, but he didn’t need to be. He could be pretty dang quiet. On defense, I tried to fire up everybody, but Charles just lined up and would nail you.”

The ’71 season was marked by tragedy as lineman Bill Arnold from Staten Island, New York, died after collapsing during a hot afternoon practice in early September. It was an era when water and rest periods weren’t customary during football practices even when the weather was oppressive.

“I was usually OK in the heat, but there were some practices I lost anywhere from 12 to 16 pounds in water weight,” Waddell says. “When I would run, my shoes would be squishing because they were soaking wet.”

He caught 41 passes for 571 yards and seven touchdowns for the Tar Heels, including a school-record three TDs against Clemson, and earned All-America honors as a senior when he and Elkins served as co-captains. He joined the junior varsity basketball team as a sophomore but got moved up to Dean Smith’s varsity squad and played in 11 games in 1973. (He also participated on the track and field team in the shot put and discus that spring.)

Waddell played basketball as a junior, too, but broke his wrist in a game against Virginia and wasn’t in Carmichael Auditorium on March 2, 1974 when Carolina pulled off a magical comeback against Duke, rallying from eight points behind with 17 seconds left to tie the game on a long Walter Davis shot, then defeating the Blue Devils 96-92 in overtime. Charles was in Kenan Stadium, on the sidelines of a spring football practice.

“I was listening to the game with some of the trainers on the radio of an old station wagon they used to bring stuff out onto the field,” Waddell says.

A fifth-round selection by the San Diego Chargers in the 1975 NFL draft, Waddell returned to Chapel Hill in the late 1970s when his NFL career was over. He worked with Paul Hoolahan as one of UNC’s first strength and conditioning coaches. The duo also oversaw academics for Tar Heel athletes. In the early 1980s, Waddell decided to pursue an MBA while working part-time in game operations. He picked up additional income when Roy Williams, then an assistant basketball coach charged with delivering The Dean Smith Show to television stations each weekend during hoops season, shared the duty with Waddell who earned $100 every other week.

“They produced the show in Greensboro, so the weeks Roy didn’t do it I would pick up the tapes there at 3 or 4 o’clock on Sunday morning,” Waddell says. “I’d drive to the TV station in Asheville, drop one off there, then go on to Charlotte and leave one there, then come on home to Chapel Hill. Getting a hundred dollars was a big deal in those days.”

After securing his graduate degree, Waddell worked in investment banking at NCNB for seven years. When former Tar Heel basketball player Jim Delaney became commissioner of the Big 10, he hired Waddell to be an assistant commissioner. “I was enjoying investment banking but figured I would get back into college athletics at some point,” Waddell says. He worked at Big 10 headquarters in Chicago for four years before returning to North Carolina and a position with Richardson Sports and the Carolina Panthers in part to be closer to his mother after his dad passed away in 1990 (Emma Waddell died in 2017 at age 95.)

The Waddells especially loved watching the son they nurtured to succeed compete during his college days. “They really enjoyed my career at North Carolina,” Waddell says. “They got to be really good friends with some of my teammates and their parents. They went to all our home games and a lot of the road games. I know the first time either one of them got on an airplane was when they flew out to watch us in the Sun Bowl in Texas. I know they enjoyed that experience.”

Waddell’s business and athletic administration career also gave his parents satisfaction. When he surveys it all — from the boyhood games in the neighborhood and the town parks, to UNC, the NFL and beyond — he’s pleased. “I interviewed for some athletic director jobs over the years but never got one,” he says. “But I’ve had a good career and feel good about the things I’ve achieved.”

On and off the field, he has stood out like the typewritten homework he hunted and pecked at dawn all those years ago. PS