Hometown

A Dann for All Seasons

And a missing face in the crowd

By Bill Fields

Thousands of people will be in Pinehurst for the 124th U.S. Open. I’m going to miss someone who won’t be there.

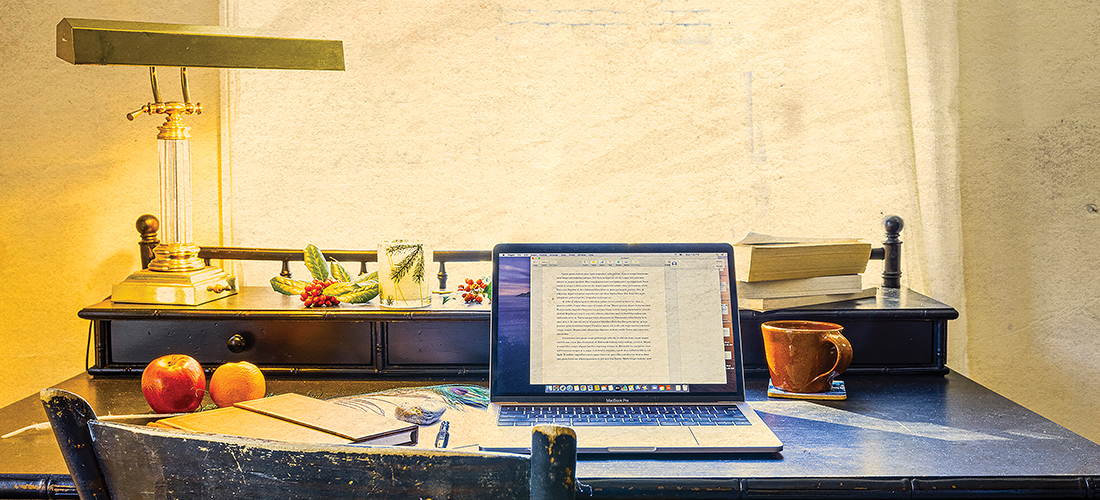

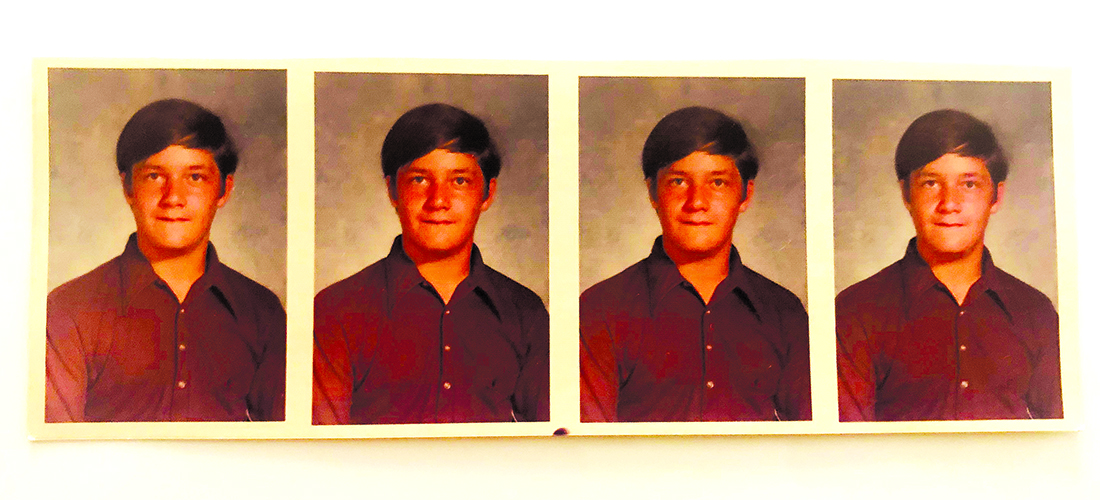

I saw Michael Dann for the last time in 2014 during the back-to-back Pinehurst Opens. We played golf at Pine Needles, the final round of what had to be hundreds together, most of them in the 1970s when I was a teenager, he a young man, two golf nuts on a search for the secret.

His was the lower score that June day, as it usually was, although there was one notable exception in the late ’70s when we were playing at Hyland Hills in qualifying for the town amateur. I came to the 18th tee three under, needing a par to break 70 for the first time. In those days there was a bunker behind the 18th green. Pumped up, I found it with my approach and had to get up-and-down for 69. When my sand shot trickled into the hole for a birdie, Michael was happier than I was. I don’t have the scorecard or the ball from that day but can still hear him, my gallery of one, shouting, “William Henderson!” as he liked to do.

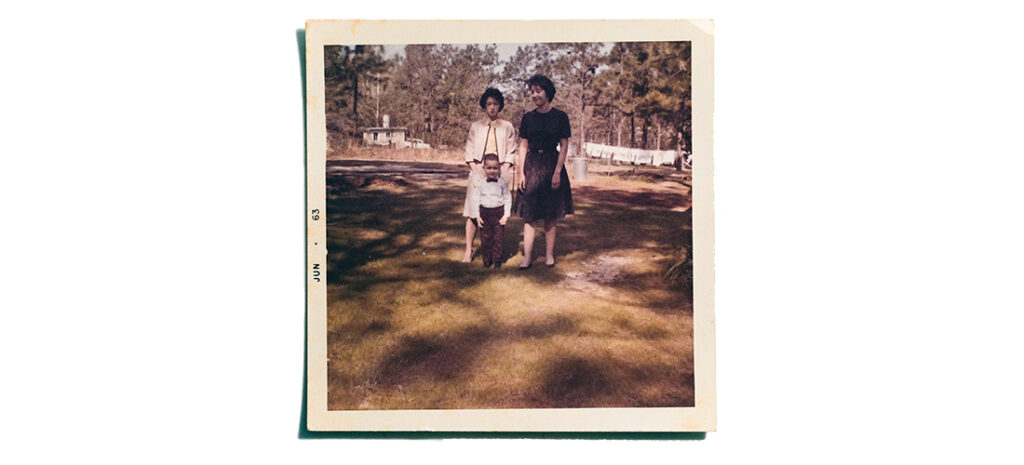

Despite a 10-year age difference, Michael was one of my best friends in those days — buddy, sounding board, mentor. We clicked from the start. I met him in 1973 when he was a volunteer instructor for Recreation Department golf lessons at the Campbell House field. I could get the ball airborne in a group of mostly rank beginners, and soon Michael and I were playing and practicing together.

We played in the heat and the cold. Once, arriving at Foxfire for a frigid one-day event, I wondered why there was a roll of Saran Wrap in Michael’s trunk. “For our feet,” he said. They stayed warm, if a bit sweaty. When Michael and Jeff Burey played a 108-hole charity marathon for National Golf Day in 1978, Mike packed a jar of pickle juice in case he started cramping on the hot summer day.

Michael had a poor man’s Hale Irwin action — a steeper plane on the way down than going back — that was grooved from years of playing a lot. He shot in the low- to mid-70s plenty of times we played, so it was no surprise when he averaged 76.50 for the six-round fundraiser at Pinehurst.

He was a writer-photographer at Golf World magazine in the 1970s, and even though he was just in his 20s, had a seasoned background in the game. His father, Marshall, had been a sportswriter in Detroit before becoming the executive director of the Western Golf Association in 1960, a post he held for 28 years. Michael grew up in the Chicago suburbs and studied journalism at the University of Illinois, where he was on the golf team. His dad ran the Western Open as part of his duties, so it made sense that the son did his master’s thesis on “Preparation and Operation of a Major Professional Golf Tournament.”

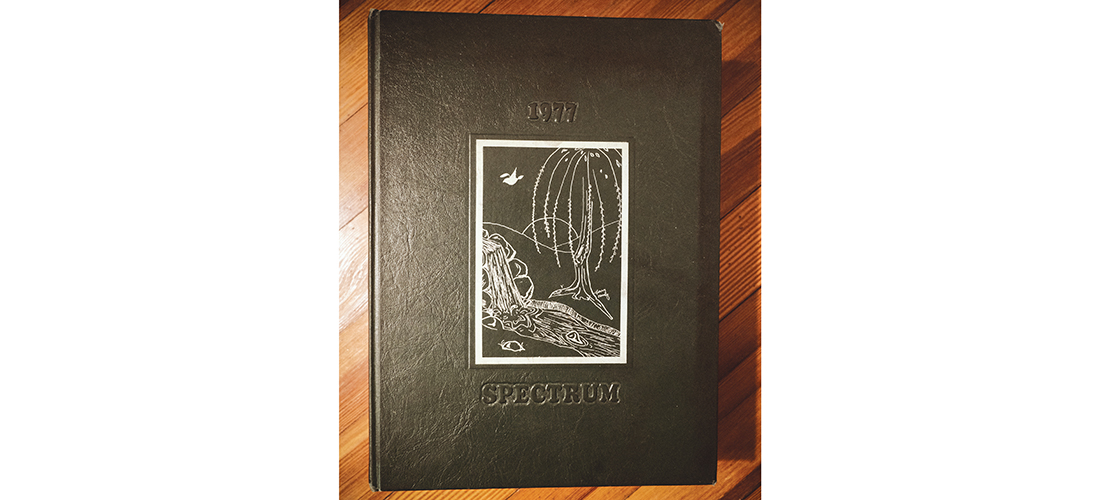

When he became director of the World Golf Hall of Fame, Michael had a chance to follow in Marshall’s footsteps and run the 1981 Hall of Fame Tournament. Because of a lack of sponsorship dollars, the event was in jeopardy until a couple of months prior to the September dates. When they had rustled up enough money to make it happen, Michael hired me, fresh out of UNC, to handle public relations. Michael and I didn’t get to play much golf in that period, but we had plenty of laughs. You are forgiven if you don’t recall that Morris Hatalsky was our champion.

Michael and his wife, Dianne, had two sons and a daughter. From 1992 until his unexpected death in July of 2014, at 65, he worked at the Carolinas Golf Association as director of course rating and handicapping. It was a long title that simply meant many folks around the two states had the opportunity to spend time around him, whose kindness, wit and love of golf made him hard to forget.

His friends and colleagues at the CGA play their annual staff tournament, The Dann Cup, in his honor, and many of us think of him often. PS

Southern Pines native Bill Fields, who writes about golf and other things, moved north in 1986 but hasn’t lost his accent.