Hometown

Teach a Man to Fish

Or just get in line at Hoskins

By Bill Fields

In a modest fishing career that produced nothing for the wall and little for the table, I wish I’d caught one flounder, because I sure ate plenty of them.

Other than whatever mystery-from-the-sea comprised the fish sticks in the freezer that would be supper if my working mom had a particularly long, tough day, flounder was the fish of my childhood. It would have made my beach vacation to land a summer flounder, but Paralichthys dentatus was as elusive as winning a large stuffed animal at Skee-Ball in the Ocean Drive arcade.

On a good outing, Dad and I, equipped with the gear we usually took to Moore County ponds in pursuit of bream or bass, would catch our share of tiny spot, croaker and whiting from the Tilghman Pier, trinkets from the surf. But even if I could convince him to splurge on “flounder rigs” that kept the hooks baited with shrimp floating just above the bottom where the species supposedly liked to dine, instead of flush on the ocean floor where the less desirable fish scavenged, we’d come up as empty as the shark-fishing men with heavy-duty tackle at the far end of the pier.

There was no chance of Curt Gowdy reaching out to us to appear on The American Sportsman.

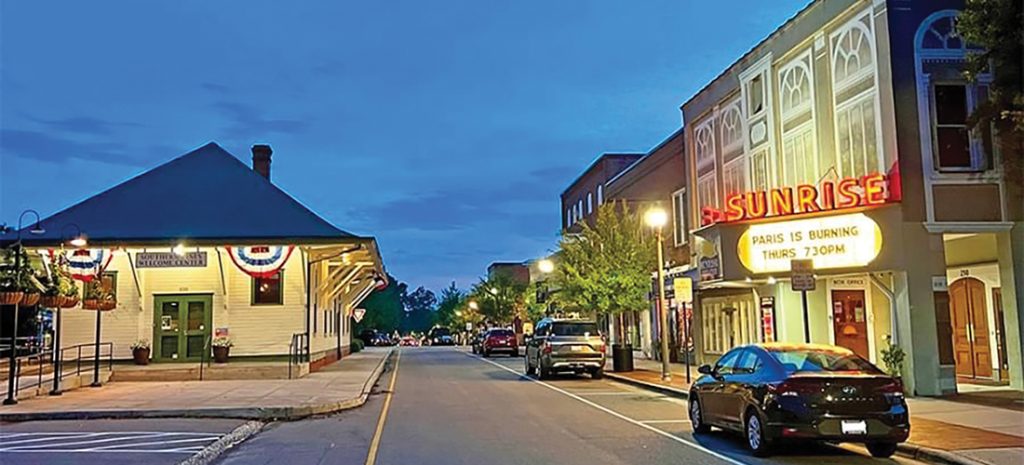

The futility of fishing for flounder went away, though, if our family was going to Hoskins Restaurant that evening. The Ocean Drive eatery had lost a needed apostrophe in its sign sometime between when it opened in 1948 and when we were patronizing the place a couple of decades later but maintained a mastery of fried seafood — particularly flounder.

Hoskins was one of the first things we’d sight when driving into Ocean Drive headed for the rental cottage or motel where we were staying. It wasn’t a matter of if we were going to go there during our stay, but how many times.

No one got out of sorts if there was a wait to get in. We knew the air conditioning would be cranking — at a time when AC still wasn’t commonplace — and we could count on the quality of the food. I went through a fried shrimp phase but always went back to the flounder.

The filets of the mild-tasting flatfish were sizable and the outside golden brown and never heavy. Paired with the can’t-eat-just-one hushpuppies, there was nothing better. Even a midday sno-cone and corn dog from a strand vendor couldn’t compete with a Hoskins’ flounder plate.

Fortunately, we had fried flounder options the other 51 weeks of the year.

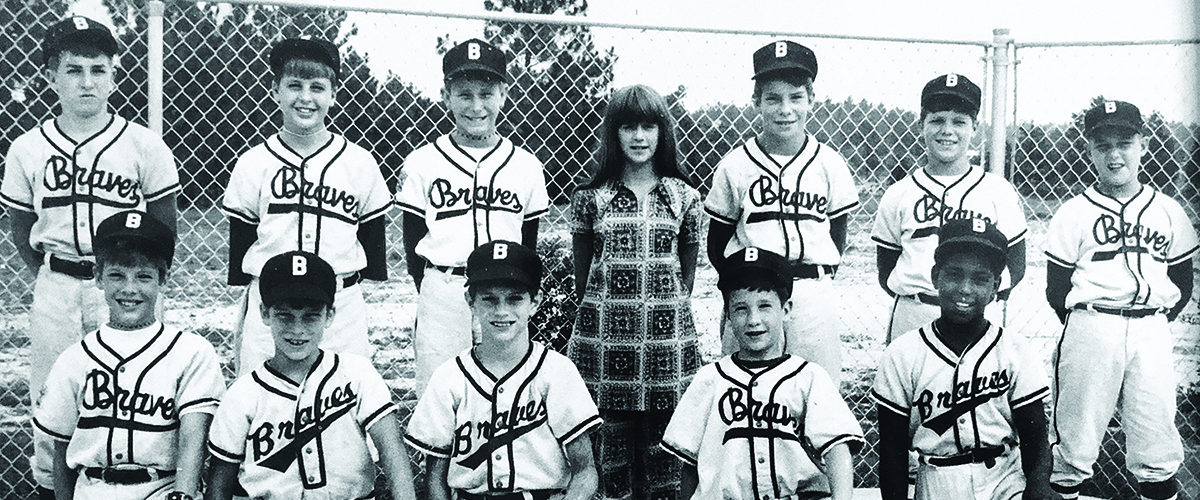

Russell’s Fish House on Highway 22 on the outskirts of Southern Pines opened in the mid-1960s offering all-you-can eat fish for $1.50. We went many a Friday or Saturday night, and I eventually worked there, first as a busboy, then in the kitchen. I cooked the hushpuppies for a time and some of the other teenagers working for owners Larry and Mary Russell handled the fries and manned the grill.

The flounder, though, was the purview of an older man named Herbert, who masterfully tended his bubbling fryer of peanut oil and didn’t want the youngsters messing with his fish. We could be a loose bunch, no strangers to horseplay while cleaning up at the end of a long night, but we obeyed Herbert.

Given the volume of fish that was served, the quality of the flounder was consistently good even if some of the fillets weren’t as plump as those we ate on vacation. My appetite for flounder would wane occasionally because I was around it so much for several years, including filling lots of takeout boxes, but there were still times when I savored a plate for my meal at the end of a busy shift.

Our third option for flounder in those years was at my brother-in-law Bill’s restaurant in High Point. Everything was good on the broad menu at Brinwood — fried chicken, country-style steak, spaghetti, meatloaf — but his fried flounder was especially tasty.

After enjoying my brother-in-law’s light, never-greasy fish for several meals, I was convinced the only thing Hoskins had on Brinwood was the beach down the street. PS

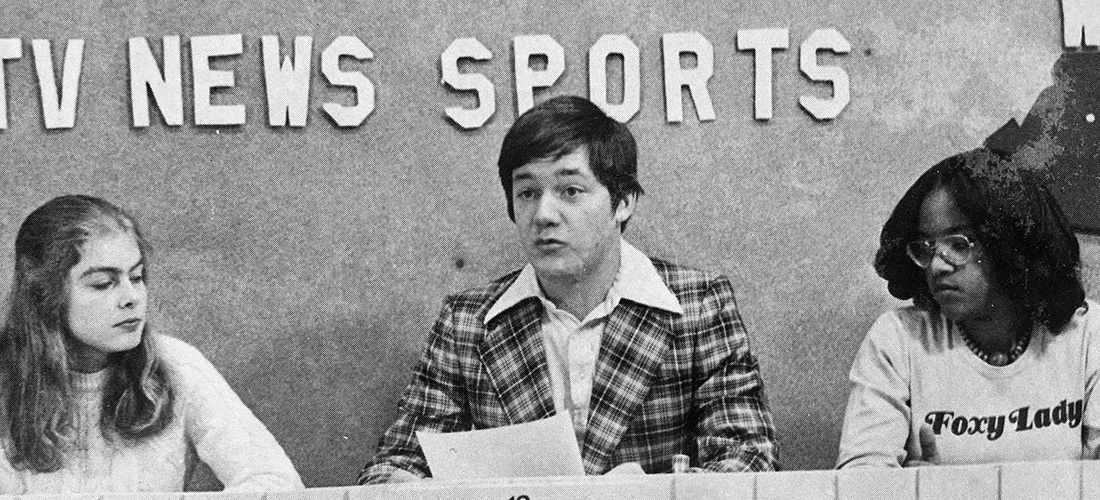

Southern Pines native Bill Fields, who writes about golf and other things, moved north in 1986 but hasn’t lost his accent.