Home Again

The World Golf Hall of Fame returns

By Bill Fields

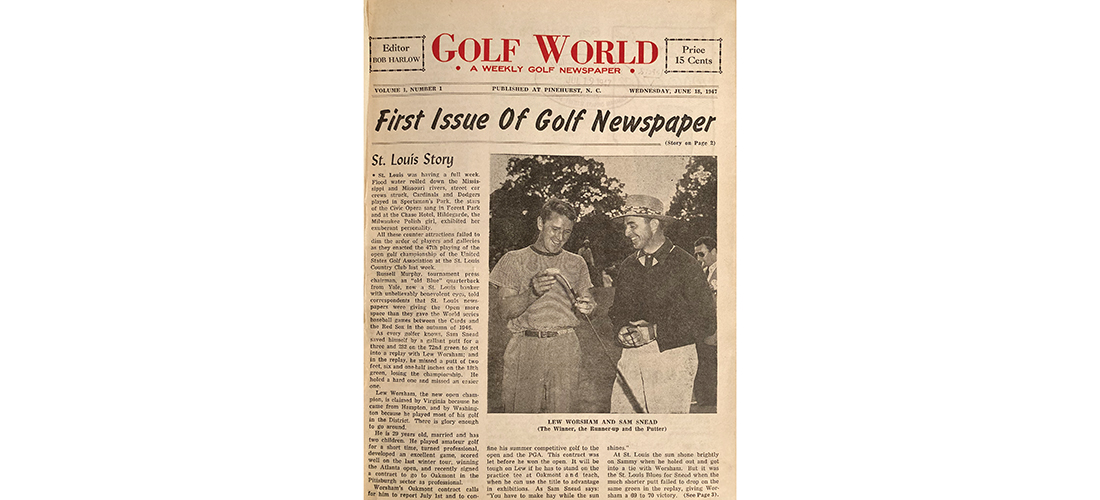

As a 15-year-old, on a Sept. 11 when that date was just another day, I watched the World Golf Hall of Fame get off to a rousing start in Pinehurst. They let us out of school early so we could see President Gerald R. Ford, who had committed to the appearance before his very recent promotion, and a dais full of golf legends as the facility was dedicated and the inaugural class of 13 individuals was inducted. In a subdued dark suit, Ben Hogan looked as if he had stepped out of 1953, but Jack Nicklaus’ red sport coat and wide tie made sure everyone knew it was 1974.

Like the Golden Bear’s attire, the World Golf Hall of Fame would go out of fashion quickly. Exhibits were thin. Honoree bronzes were unattractive. Attendance was sparse. As I knew from working there in 1981-82 and having put out buckets between writing press releases, the roof leaked badly. There were plenty of good intentions and no lack of effort among those involved with the WGHOF over the decades — both in Pinehurst and in St. Augustine, Florida, where it has been situated off Interstate 95 since 1998 — but in both locales it has been the institutional equivalent of a golfer with potential who can’t shoot a number.

The third time just might be the charm.

As announced this summer, the World Golf Hall of Fame is returning to its roots in 2024, when it will become part of the USGA’s Golf House Pinehurst, a 6-acre campus being developed not far from the Pinehurst Resort and Country Club main clubhouse. Fifty years after the hall’s first honorees were inducted a pitch shot away from the fifth tee of the Pinehurst No. 2 course, induction ceremonies will coincide with the 2024 U.S. Open on No. 2. In 2029, when the U.S. Open and U.S. Women’s Open are held in consecutive weeks as they were in 2014, another group of Hall of Famers will get their due.

If things go as planned in the handful of years between those U.S. Opens, the relocated and reimagined World Golf Hall of Fame will have become what many hoped for a long time ago: a secure, vital part of the golf landscape where the past is treasured and shown off in a thorough and distinctive way that makes visitors want to come.

“We look forward to celebrating the greatest moments and golf’s greatest athletes by including the World Golf Hall of Fame as an important part of our Pinehurst home,” said Mike Whan, CEO of the USGA. “Simply put, it just makes sense.”

The Hall of Fame will continue to be an independent organization, part of the World Golf Foundation, and will still administer the induction process. (Who votes, who does or doesn’t get in, and how honorees are categorized remain legitimate, longstanding questions that aren’t answered by the move.)

But the USGA, whose Golf Museum and Library in Liberty Corner, New Jersey, are first-class, will be in charge of day-to-day operations in the new location and will be able to draw upon its huge collection of golf artifacts — some of which never get seen by the public — to beef up what is on display in Pinehurst. The USGA and Hall of Fame will collaborate on digital and interactive content about WGHOF members.

There will never be one, see-everything-important repository in golf, just as there is no single art museum housing all the great works. The USGA’s counterpart across the Atlantic, the R&A World Golf Museum in St. Andrews, possesses many items. Some valuable collectibles are in private hands around the globe. For fans of the guy who wore the garish jacket in ’74, the Jack Nicklaus Museum in Columbus, Ohio, is the place to go. But as someone who occasionally played major championship highlight films on a 16 mm projector to a mostly empty theater in the old Pinehurst facility, the prospect of a fantastic visitor experience in the forthcoming home is enticing.

In an ideal world, the Hall of Fame wouldn’t have begun as a commercial venture, would have been housed in a suitable building instead of a white elephant, and never would have left Pinehurst. In the real world, it’s wonderful to see it coming home. PS

Southern Pines native Bill Fields, who writes about golf and other things, moved north in 1986 but hasn’t lost his accent.