HOMETOWN

The Way We Were

Let your fingers do the walking

By Bill Fields

While cleaning out my childhood home almost a decade ago, I held on to some random items, one of them having been tucked in a cabinet below the wall-mounted phone in the hallway, an instrument through which good and bad news, salty gossip, and the time and temperature had been received for decades. In the final days of 692-8677, the long cord hanging toward the floor looked like it always did, a tangled mess that made privacy or pacing difficult.

I salvaged an old phone book that had been published in November 1975, its white and yellow pages good for the following year. “A Century of Telephone Progress” was heralded on the cover, along with renderings of antique and current phones — a state-of-the-art pushbutton model! — and the bearded visage of Alexander Graham Bell, who received a patent for the telephone on March 7, 1876.

Perusing the thin 6-by-9-inch volume of residences and businesses compiled by the United Telephone Company of The Carolinas five decades after it landed in our mailbox is nothing short of time travel to the way we were, before the Southern Pines area had grown and phones had shrunk.

Some of the “instructions” in the directory’s early pages are so rudimentary they are a reminder that, 50 years ago, a land line was considered a modern marvel.

“One way to avoid wrong numbers is to keep the area code and number before you as you dial.”

“When you make a call, give your party time to answer — about 10 rings — before you hang up. This could save you having to make a second call later.”

“You can save money by dialing all your calls direct without involving an operator.”

Making an out-of-state call? There was a 35 percent discount on weekday evenings and 60 percent off on Saturday and Sunday. Trying to describe a “collect” call to someone who came of age during the cellphone era is like explaining when gas was 49 cents a gallon or that airplanes had smoking sections.

By the time this directory came out my father was a policeman, and we had elected to have an unlisted number, not that teenagers joyriding through the Town & Country Shopping Center parking lot to whom he gave a warning would have done us any harm. My Grandmother Daisy, born 16 years after Bell’s invention, and Uncle Bob, both Jackson Springs residents, are listed.

So many familiar names were in the phone book: neighbors and friends, teachers and pastors, doctors and dentists. If you needed to reach the editor of The Pilot after business hours, Ragan Sam was on page 87; the owner of radio station WEEB, Younts J S, could be found on page 112.

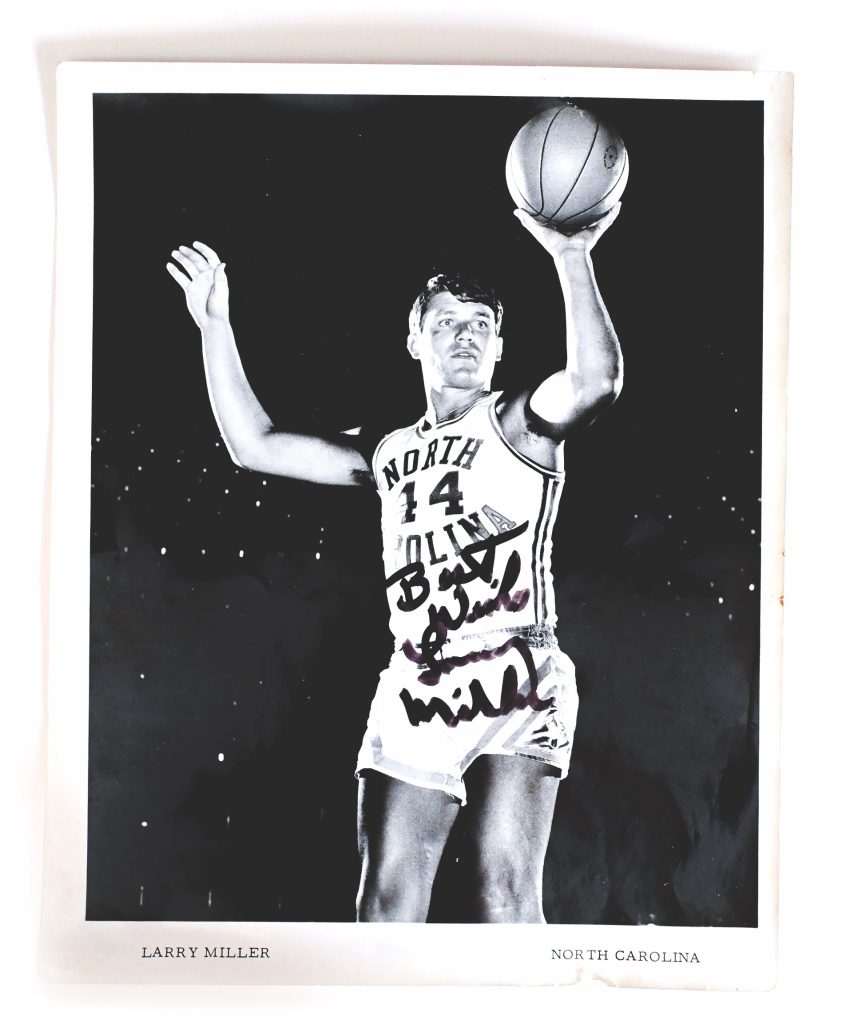

There were lots of Blues and Browns, Davises and Fryes, Jacksons and Joneses, McKenzies and McNeills, Smiths and Thomases. Perhaps more Williamses than any other name, among them John W, otherwise “Coach” to so many for so long.

When you “let your fingers do the walking in the yellow pages” there was plenty to see.

Remember “Service Stations” where you’d get your windshield cleaned and oil checked while filling up? Dezalia Phillips 66, Poe’s Texaco, Red’s Exxon, Styers Gulf were among the dozens of such establishments listed in the yellow pages.

Restaurants? There was The Capri and The Chicken Hut, Dante’s and Duffy’s, Lob-Steer Inn and Park-N-Eat, Cecil’s Steak House and The Sandwich Shop, Mr. Flynn’s and Tastee Freez. None of those exist today, but Bob’s Pizza (“Call for Quicker Service”) does.

St. Joseph of the Pines was still a hospital. Mac’s Business Machines could set you up with a typewriter. You could get lodging at the Belvedere Hotel or Fairway Motel, groceries at A & P, Big Star, Piggly Wiggly or Winn-Dixie (“The Beef People”). The Glitter Box is no more, but Honeycutt Jewelers still sparkles.

Among the clip art (dogs, golfers and termites) and bold fonts, one of the categories caught my eye: “Ice.” Half a dozen places were listed, including Brooks Min-It Market and Ice Masters Service of Carthage, which boasted “clean, hard ice cubes” and “ice never touched by human hands.”

Now, we hold computers in our palms and text with our thumbs. That’s “person-to-person” these days.