Golftown Journal

Ticking the Ross Boxes

When a passion becomes a book

By Lee Pace

It was an inauspicious beginning to a golf career, this young investment banker with a background in surfing and tennis being recruited by his boss to fill out a foursome on Pinehurst No. 2 one day in 1973. Brad Becken’s job at Goldman Sachs was managing the firm’s business in the Southeast, so he regularly attended the North Carolina Banking Association annual meeting at Pinehurst.

“Usually, I played tennis with the wives,” he says. “The second year, my boss needed a fourth for golf. I said, ‘I don’t play golf.’ He said, ‘Well, you are today.’

“I was in sneakers with rental clubs and picked up nearly every hole so as not to ruin it for the others. I thought that was it for my golf career. But the next year, he asked me to play again. I thought, ‘You’ve gotta be kidding.’ It was the same result.

“He mercifully never asked me again. My first taste of golf and Pinehurst was memorable, though not necessarily in a good way.”

Becken did, in fact, get serious about golf when he moved to Los Angeles with the firm in the mid-1980s and later joined Los Angeles Country Club. Over the next three decades, business travel and client relationships were perfect for fueling an evolving love for the game. He retired in 2005, and he and wife, Ann, decided to return to the East, settling in Chapel Hill.

He joined Chapel Hill Country Club and, in 2010, took a friend visiting from Los Angeles to play golf. Afterward club pro Rick Brannon suggested they play Hope Valley, a 1926 Donald Ross design just a few miles away in Durham. Brannon made a phone call to set up a game, and Becken was enthralled with the old-world charm of the neighborhood and the way the holes were laid on the hilly ground by Ross, working without heavy machinery and his design perspective spawned from his roots in Dornoch and St. Andrews, Scotland.

“I immediately figured out I’d joined the wrong club,” Becken says. “I liked the variety at Hope Valley and the fact that the design never felt forced. And like most Ross courses, you didn’t feel overwhelmed if you weren’t a great golfer. You don’t have to be a great golfer to enjoy a Donald Ross course. For a higher handicapper like I am, there is a way to play his courses. You can plot your way around and enjoy it.

“I told Rick how much I liked it and he said, ‘Well, there are a lot of Ross courses in North Carolina.’”

Becken soon joined Hope Valley and set off to quench this newfound thirst for Ross golf courses. He joined The Donald Ross Society in 2012, was elected to the board in 2016, and in 2023 was serving the last of a five-year run as president. He realized around 2015 that he had played some 225 Ross courses.

“Up until then, I had never really contemplated trying to play them all,” he says. “I was having fun and the more I saw, the more I liked it. So I kept at it. I was averaging 120 courses a year.”

By the end of 2017, Becken had played 359 Ross courses, give or take a few that have closed since the quest began, and thought he had played every Ross course that was still open. Then he came across Chris Buie’s book, The Life & Times of Donald Ross, and learned there were about half a dozen more courses he’d not played. He knocked them out so his total stands at 365 courses.

“As this was going along, people said, ‘You ought to write a book,’” Becken says. “I said, ‘I’m a banker, not a writer.’ As president of the Ross Society, we were always getting questions. We would sort of answer them, and I said, ‘We can do better than this.’ I started analyzing what I had learned. By then I had copies of every hole and green drawing I could find. I might have had 1,500, plus all the photos I had taken and collected. Finally, I started to think about a book but didn’t know where to get started.”

In 2020, he was invited by Golf Club Atlas editor and co-founder Ran Morrissett to answer a litany of questions for the site’s “feature interview.” Morrissett provided the questions and Becken sat down to write his answers.

“That was January 2020,” says Becken, 75. “That got me started. I just expanded from there. That finally got me going.”

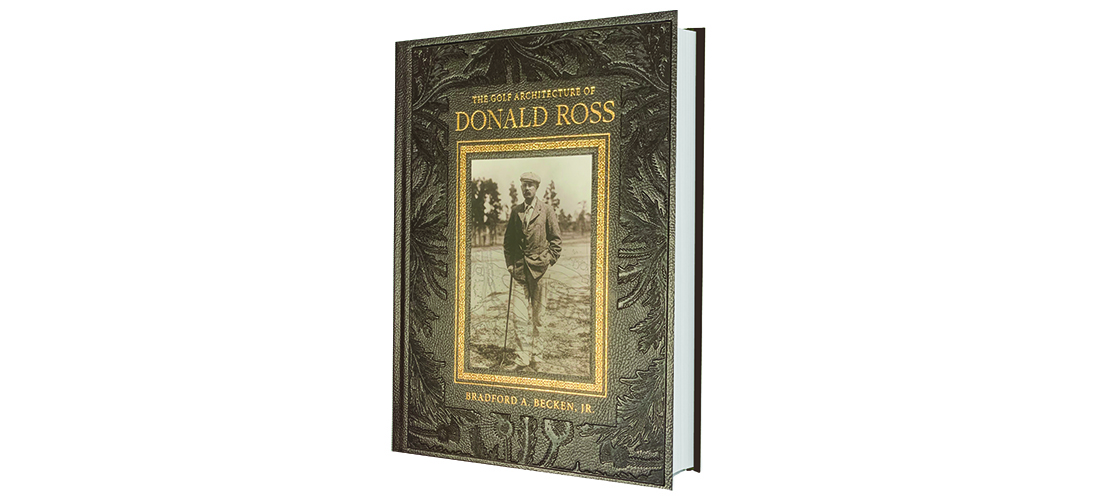

The result is a book published in the fall of 2022 by The Classics of Golf. The Golf Architecture of Donald Ross is as mammoth as Ross’s body of work from 1900 through his death in 1948 and Becken’s quest to play them all. It’s 9×12 inches, 352 pages, an inch-and-a-half thick, weighing three pounds. The tome includes gorgeous spread photos of Ross courses, hole diagrams, telegrams and correspondence. Becken draws heavily on his ever-present camera as he played the courses and his insatiable appetite for detail. He created a spreadsheet matrix covering more than 30 data points and observations for each hole and uses that research to analyze the parts that result in the whole of Ross’s design inventory.

“As the title suggests, this is a comprehensive look at Ross’ architecture from routings to bunker schemes to greens to breakdowns of his best one-, two- and three-shotters,” Morrissett says. “If you are an architecture geek, you will get lost in the book for days.”

Of local interest he notes there are no drawings for three of Ross’ Sandhills-area masterpieces — Pinehurst No. 2, Pine Needles and Mid Pines.

“Since he spent half of each year in Pinehurst, where he could supervise the work, there was no real need for drawings,” he says.

Further, Becken uses his inventory of Ross drawings and his experiences having putted across more than 6,500 Ross greens to draw an opinion on the nature of No. 2’s ubiquitous inverted-sauce putting greens.

“Many Ross fans associate the turtleback greens on Pinehurst No. 2 as emblematic of his work, but that is not the case,” Becken asserts. “In fact, looking at the body of available drawings, such greens appear to be more of an exception, leading some to attribute the shape to years of top dressing and other maintenance practices rather than what was originally envisioned by Ross.”

An important tenet to the book is Becken paying tribute to The Donald Ross Society, which was formed in 1989 and since has grown to some 500 Ross aficionados. Proceeds from sales of the book are being divided equally between The Donald Ross Society Foundation and The Tufts Archives in Pinehurst. He estimates the Ross Society has given $150,000 to the Tufts Archives over the years, and the group recently gave $30,000 to Asheville Municipal Golf Course for a master plan to serve as the cornerstone to a $3.5 million renovation of the 1927 Ross course that had fallen on hard times.

“We believe Donald Ross was superior to any golf course architect practicing today, and his courses are works of art that should be treated as such,” Becken says. PS

Chapel Hill-based writer Lee Pace has written histories of five clubs featuring Ross courses — Pinehurst, Pine Needles, Mid Pines, Forsyth Country Club and Biltmore Forest Country Club. Reach him at leepace7@gmail.com and follow him on Twitter @LeePaceTweet.