Catching up with a brother act

By Lee Pace

The sports world is chock-full of successful sibling stories. From coaching you have Jim and John Harbaugh, and Rob and Rex Ryan. From quarterbacking, exhibit A is certainly Peyton and Eli Manning. The tennis world features sisters Venus and Serena Williams, and brothers Bob and Mike Bryan. The Busch boys (Kyle and Kurt) have won often on NASCAR tracks, and you cannot get close to center ice without stumbling on a Stahl (Eric, Marc, Jordan, Jared).

Golf from way back had Lloyd and Ray Mangrum combining for 41 PGA Tour wins, from a generation ago Lanny and Bobby Wadkins emerging out of Richmond, and today Francesco and Edoardo Molinari are forces on the European Tour.

So what to make of Zachary and Joshua Martin, the dynamic brotherly golf duo from Pinehurst now plying their trade at the University of North Carolina?

“It’s an interesting sibling dynamic,” says Pinehurst teaching pro Kelly Mitchum, who gave both brothers lessons during their high school days. “They’ve competed against each other, but I’ve never sensed anything but them truly rooting for each other. They always wanted each other to do well.”

“It’s like they’re each other’s biggest cheerleader,” adds UNC coach Andrew Sapp, who brought Zach into the Tar Heel program in 2013 and Josh in 2015. “I really haven’t seen a sibling rivalry between the two. I was out of town with Josh once at a tournament and we heard that Zach had lit it up in a qualifying round back home. Josh was genuinely excited to hear his brother shot a good score.”

The Martin brothers have acquired over their dozen years in Pinehurst quite the golfing pedigree. The family was profiled in the Wall Street Journal in 2008 for its adventuresome move from Wilson in Eastern North Carolina to Pinehurst so that the boys could have access to the village’s largesse — courses, instructors and a 24-7 golf ambience. Bowie and Julie Martin gave their boys opportunities in all manner of sports as youngsters, but in time they gravitated toward golf. Bowie’s job as owner and president of a family business involved in manufacturing and distributing premium table tennis equipment worldwide gave him the freedom to relocate. At the time, Zach was 10 and Josh 8.

“I was too young to know how crazy it was with our parents having a business in Wilson,” Josh says. “But it worked out well for everyone.”

“I can better appreciate the history of Pinehurst as I’ve gotten older,” Zach says. “When we first moved, all I saw was a bunch of golf courses. Then you understand more about the North and South Open, the PGA Championship back in the 1930s, you definitely get a better appreciation. I think being in Pinehurst has definitely helped both of us develop as golfers.”

Zach first caught the attention of Sapp while shooting a 66 at Mid Pines in a junior tournament in 2012. “He made everything he looked at,” Sapp remembers. “He’d bang it, go find it and drain another birdie.” Zach’s birdie putt in a playoff on the 17th hole at Pinehurst No. 8 secured the state championship for Pinecrest High in 2013.

Josh won a pair of Donald Ross Memorial titles and four U.S. Kids World Championships, held each August in the Sandhills, and in 2014 at the age of 17 became the youngest winner ever of the North Carolina Amateur Championship.

And they evolved with a single-minded focus that’s an oddity today with so many social media and youth league sports distractions.

“They never canceled a lesson, never were late for a lesson,” Mitchum remembers. “No matter the weather, they were on time and ready to work.”

Josh’s ability in particular earned him somewhat legendary status around the resort and community — originally the family rented a house on Pinehurst No. 3 and several years later moved to Pinewild Country Club. Enter a Google search for Josh Martin and you’ll find one subjective yet interesting blog listing him among the top 10 child golf prodigies of all time (along with Tiger Woods and Michelle Wie), and included is one unsourced account of a golfer at Pinehurst allowing this 7-year-old kid with ketchup on his shirt to join him on No. 4 and Josh shooting a 78. The grown-up asked the kid for an autograph after the round was over.

“We joined up with older people all the time,” Zach says. “At first, they were a little hesitant because we were so young. No one wants to be held up by little kids who are just learning. But once they saw we could play, they enjoyed it. We had a good time playing with other people and made some friends over the years.”

Sapp says he often runs into golfers and families from around the country and as far removed as China who knew of Josh’s dominance in the U.S. Kids World Championship and Rich Wainwright, an executive at Pinehurst and assistant golf coach at Pinecrest High, whistles looking at Josh’s prep era that included him, Eric Bae (now on the golf team at Wake Forest), Doc Redman (Clemson) and Henry Shimp (Stanford) and says, “That’s U.S. Open material there.”

Zach has caddied for Josh twice in the U.S. Amateur, and this spring both are competing for regular playing spots on a Tar Heel lineup that is likely the deepest and most experienced it’s been in many years. Zach is 22 and a senior, Josh 20 and a sophomore.

Bowie Martin says one of the elements of golf that he and Julie as parents favored in their children’s evolution was the emotional control and manners one had to learn to succeed in the sport. More than a decade into it, that’s proven prophetic.

“Etiquette, patience, self-policing are parts of golf,” Bowie says. “You don’t have officials on top of you. In golf, you monitor yourself. That’s the neat thing about it. If you hit a bad shot, you might have five minutes before you can get it back. Patience is huge, staying even-keeled over a longer period of time.”

To put the Martins’ games in nutshells, Zach plays a power game, Josh a precision game. Zach hits the ball “forever,” as Sapp says, and can overpower a course. He shot the course record at UNC Finley, a 1999 Tom Fazio design that can stretch to 7,220 yards, with a 63 last fall, then broke it two weeks later with a 62.

“Off the tee, he’s probably the longest guy on the team,” Josh says. “When he gets it going, he can go really low. He makes a bunch of birdies and can beat anybody.”

Zach might bomb his drive over bunkers on a par-5, while Josh, by no means short, is playing a more tactical game with carefully aimed hybrids off certain tees. Josh has a legendary short game.

“He knows how to get the ball in the hole,” Zach says, slowing down and enunciating in the hole with extra bite. “I can’t emphasize that enough. He knows damage control.”

“Josh doesn’t miss fairways, doesn’t miss greens, and makes a few birdies along the way,” Sapp adds. “When both are on, they have tremendous potential in college golf.”

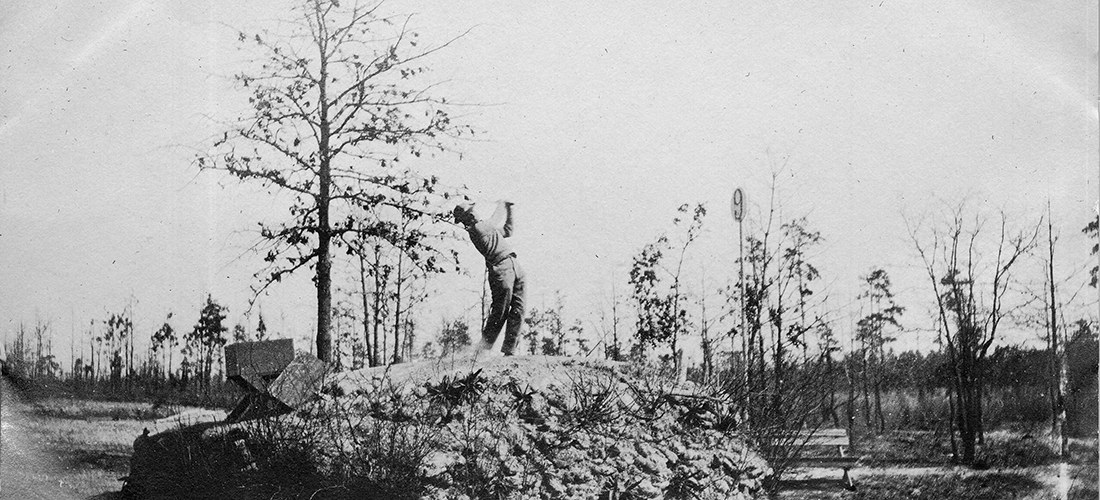

I first met the Martins in the spring of 2009 when I wrote their story for the May 2009 PineStraw. Their swings were being videotaped by Eric Alpenfels, also a Pinehurst instructor and colleague of Mitchum’s, at the base of the Maniac Hill practice facility. The building blocks were apparent then — skill level, love of the game, focus, parental support.

“The boys would like to play college golf,” their dad said at the time. “After that, who knows? Golf offers a lot of opportunities to play as part of your business. You can be a teaching pro. You can try the pro tour, but that’s a tough life. That’s not the goal. The goal is the challenge of trying to accomplish something, to master a skill and get better.”

Nearly a decade later, so far, so good. Both are good students at Carolina, Zach studying economics and Josh sports administration, but both want to play pro golf. If that doesn’t work, something in the golf industry would be fine — teaching, perhaps. And the boys have grown as siblings and friends and with no apparent rivalry gumming up the works. The elder Zach even says his younger sibling’s glitzy record flips the traditional big brother/little brother dynamic.

“His accomplishments so far outweigh mine, so I look up to him and feel like he’s mentoring me every time I play with him,” Zach says.

“We’re competitive, but at the end of the day, we put down the clubs and are great friends,” Josh says.

Stay tuned for the spring of 2017 in Chapel Hill and then beyond for Zach and Josh Martin. There’s plenty of room in the winner’s circle that houses the Mannings and Mangrums — basically everybody and their brother. PS

Chapel Hill-based writer Lee Pace has written “Golftown Journal” since the summer of 2008.