“Coincidence is God’s way of remaining anonymous.” — Albert Einstein

By Lee Pace

Another year dawns and the largesse of the Sandhills golf community continues to evoke awe and grace. Forty golf courses in a 15-mile radius, one USGA event coming in 2017, another on tap for 2019, an interesting and ambitious project to redesign Pinehurst No. 4 and create a new short course at Pinehurst set to commence this year. The populace revels in a golf-centric environment where at any point you’re liable to see a license plate like 4RT or WHIFF or GOLF’N or a pedestrian walking down a sidewalk, pronating his left wrist as if to make a solid move through the ball.

It has always fascinated and amused me to ponder the series of dominoes that fell over five years from 1895 to 1900 that allowed this “Accidental Resort” to sprout into reality. There was no big city next door to give birth to Pinehurst. There was no ocean or mountain range to make it an aesthetic or seasonable destination, no river to provide convenient access.

No, we have this “St. Andrews of American Golf” thanks to at least five unrelated but important dollops of happenstance.

— A chance encounter on a train in 1895.

James Tufts made his fortune in patenting, manufacturing and sales of apparatuses and syrups found in apothecary shops across the land and, as he neared the age of 60, turned his business operations over to subordinates. He was active in philanthropic work and sought on behalf of the Invalid Aid Society of Boston to locate a wintertime health resort for those suffering from consumption.

Col. Walker Taylor was a sharp businessman himself and had opened an insurance agency in Wilmington in 1866 following the Civil War. He traveled extensively throughout the Eastern Seaboard, and having a gregarious personality, was wont to introduce himself to perfect strangers. One day in 1895, pure happenstance landed Taylor and Tufts on the same train. They struck up a conversation, and Tufts explained his vision to Taylor.

Taylor, family legend has it, suggested that the train station in Southern Pines might be a good starting point for Tufts’ search for a site for his new resort. It was right on two of the nation’s major north-south transportation arteries — the railroad and U.S. Hwy. 1. There was cheap land available, and it was halfway between Boston and Florida. And thus Tufts did in fact search for land — and found 6,000 acres about five miles to the west of the train station in Southern Pines.

— An astute decision by Tufts to eschew the advice of a trusted aide that “golf is just a fad.”

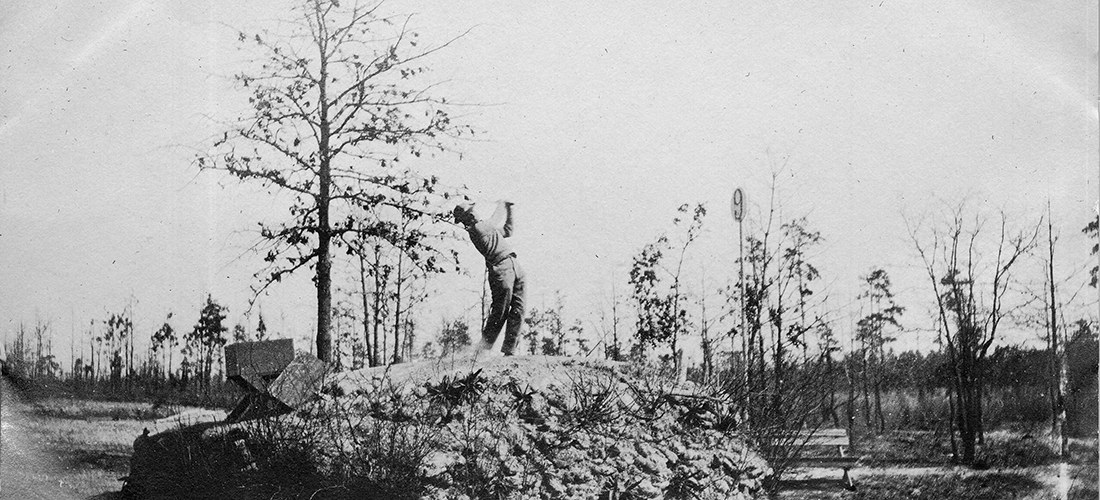

At first golf was not part of the Pinehurst dossier, and visitors enjoyed activities such as horseback riding, dancing, recitals, carriage rides, cards and a croquet-like game called roque. But in the fall of 1897, Tufts learned that guests were hitting small rubber balls with wooden sticks around the dairy fields and, in the process, aggravating the cows. So he built a nine-hole golf course as a lark in 1898, enlisting the help of Dr. D. LeRoy Culver, a Southern Pines physician who was an avid golfer, had played in England and Scotland, and understood the gist of what a course should look like. But Tufts wasn’t sold on the game’s prospects and inquired of the manager of the Holly Inn, Allen Treadway, if he thought nine more holes would be a good idea.

“Save your money,” answered Treadway, who later would be elected as a Massachusetts congressional representative. “Golf is a fad and will never last.”

Tufts’ instincts and better advice from others in his circle convinced him otherwise, and soon he embarked on the expansion of the golf course to a full 18 holes.

— A fateful coin flip in the village of Dornoch, Scotland, in 1899.

Donald Ross was a 27-year-old employee at Royal Dornoch Golf Club and was in charge of maintaining the golf course, managing the caddies, organizing competitions, and building and repairing clubs. His boss was John Sutherland, the club “secretary,” i.e., general manager. One day a golfer visiting from Boston suggested to Ross that America was ripe for growing the sport of golf, and an ambitious expert in the game might do well to immigrate and carve his niche in the game’s expansion. Ross and Sutherland both took a fancy to the idea and decided to flip a coin — one goes to America, the other stays at home and runs the club at Dornoch.

Ross won the flip.

And so he set off to America.

“My mother and Mr. Sutherland’s daughter were great pals,” says Donald Grant, a lifelong Dornoch resident and club member. “They lived side-by-side growing up. I heard the story often. I have no reason to doubt its truth.”

— That it was Boston, not New York or Philadelphia or a dozen other cities, where Ross arrived in 1899.

Ross’ contact in America was Robert Willson, an astronomy professor at Harvard and a member at Oakley Country Club in the Boston suburb of Watertown. Upon arrival in Boston, Ross phoned Willson, visited his home, and soon Willson helped Ross find work at Oakley Country Club, which was located eight miles from Tufts’ home in Medford.

Now that Tufts had a full 18-hole course at Pinehurst and a vision for building more golf, he needed a golf professional to work during the October to spring season. He learned that Oakley had in its employ a sharp young Scotsman whose responsibilities were geared around the summer golf season — an ideal fit to go South in the winter. They met at Tufts’ home in Medford. Tufts hired Ross on the spot and Ross began his new assignment at Pinehurst in December 1900. He was busy at first making clubs, managing the caddies, giving lessons and organizing competitions. He also tried his hand at designing and building new golf holes.

— And that this ground in Moore County should be predominantly sand, prompting a serendipitous connection for Ross between Scotland and his new wintertime home situated 120 miles inland from the coast.

Millions of years ago, the Atlantic Ocean covered what is now dry land along the East Coast. During the Miocene Epoch (circa 20 million years ago), the ocean receded and left a strip of what is now ancient coastline and beach deposits. The Sandhills are part of that band some 30 miles across and 80 miles long. Tufts liked the land as he first found it because its sandy composition drained quickly and was thought to have health-giving benefits.

Pinehurst was perhaps not oceanside itself. But its location was a kissing cousin to the seashore. The word “links” can be traced to the Old English word for lean, hlinc, meaning “lean terrain formed by receding seas.” The ground was perfect for golf and Ross’s tastes. It provided, in essence, an “inland links” terrain; the earth was gently rolling and sandy. Rainwater flowed through the sandy soil at Dornoch; it did so as well in Pinehurst, allowing for a golf designer’s dream environment.

“He was particularly attracted to the soil conditions here, as they reminded him of the old links land at home,” Richard Tufts, James’ grandson, said years later. “Even our native wire grass seemed to remind him of the whins he knew in Scotland.”

What if Tufts had gotten off the train in Raleigh and chosen the heavy clay environment there? It might have had no attraction had Ross landed just an hour north.

And so the dominoes fell — Tufts debarks in Southern Pines, tweaks his vision to include golf, Ross and not Sutherland comes to Boston, and Ross turns Pinehurst’s sandy ground into an American golf nirvana that draws visitors from the population centers of the East, Midwest and Deep South. By 1919, Pinehurst had 72 holes of golf and was by far the nation’s foremost golf destination.

It all makes perfect sense and hearkens the immortal words of former baseball great Yogi Berra, himself a frequent visitor to Pinehurst from his home in New Jersey: “That’s too coincidental to be a coincidence.” PS

Lee Pace has authored five books on the evolution of golf in the Sandhills, most recently The Golden Age of Pinehurst—The Story of the Rebirth of No. 2.