GOLFTOWN JOURNAL

Gimme Five

The club that can do no wrong

By Lee Pace

“Nothing is so beautiful as spring.”

Unless it’s a 185-yard par 3 with the pin on the left.

With apologies to Gerard Manley Hopkins for using his line of verse as a hook for this missive on my favorite golf club, there’s nothing that gets the juices flowing more than pulling my vaunted 5-wood (or 21-degree hybrid in contemporary parlance) and setting up for a gentle draw.

The 17th hole at my home course, Old Chatham in Durham, N.C., invites this distance and ball flight perfectly from the next-to-back tees if the pin’s rear left.

The sixth green at Pinehurst No. 2 is placed at an angle suggesting a right to left ball path and, at 200-plus yards from the Ross Tee, hits the sweet spot for a 5-wood shot, a bounce and some roll on those always firm turtleback greens.

Stand on the 17th tee at the Ocean Course at Kiawah with the Atlantic off to the right and you might well face a shot in that 185-yard range — all carry over a hazard with the water bordering the green on the right. It takes some cojones to aim a hair right over the water and curl it back — but that 5-wood is johnny-on-the-spot.

All great fodder indeed for my favorite club.

Mind you, we’re not suggesting my modest resume even sniffs the same league as Jack Nicklaus wielding his 1-iron on two of his most famous shots — to the 18th green at Baltusrol in winning the 1967 U.S. Open, or hitting the pin on the 17th green at Pebble Beach in collecting the 1972 U.S. Open championship.

Or Ben Crenshaw rolling in that mammoth putt from 60 feet on the 10th at Augusta in 1984 with his Wilson 8802 putter, the club nicknamed “Little Ben” that his dad bought for $20 out of Harvey Penick’s golf shop in Austin.

Or Phil Mickelson performing magic lob shots with the 64-degree wedge that he personally grinds to take the bounce off the trailing edge and the heel so that when he lays it open, the sole sits flush to the ground.

When I first started playing golf seriously in the 1980s, I had a Tommy Armour 5-wood with a persimmon head. That blond-colored wood with the lacquered finish set up perfectly no matter the ground — it would flush the ball off a tight lie or whip like butter through the Southern summer Bermuda grass.

Persimmon gave way to metal heads and later titanium. Fairways woods became “hybrids.” At various times, I played forged irons and later, cast clubs. I wielded Wilson irons in the early days and later played Pings and now have a bag full of Titleists.

But no matter the manufacturer or the makeup of my set of clubs, priority No. 1 has always been getting that 5-wood just right — that club that was more forgiving than the 3-wood or 3-iron and was ideally suited for approach shots into long par-4s and par-3s. Today the club of choice is a Titleist H1 19-degree with a regular flex Tensei shaft.

That 5-wood looks just right and feels just right.

It certainly did to PGA Tour player Pat McGowan some four decades ago.

McGowan played on the PGA Tour throughout the late 1970s and through the 1980s, and it wasn’t until the mid-1980s that he broached the idea of a 5-wood.

“Almost everyone carried a 1-iron, no matter who you were,” says McGowan, the director of instruction at Pine Needles Lodge & Golf Club in Southern Pines. “Most good amateurs with low single-digit handicaps carried a 1-iron. It was almost like a 5-wood was a sissy club. You carried a driver, a 3-wood and a 1-iron.”

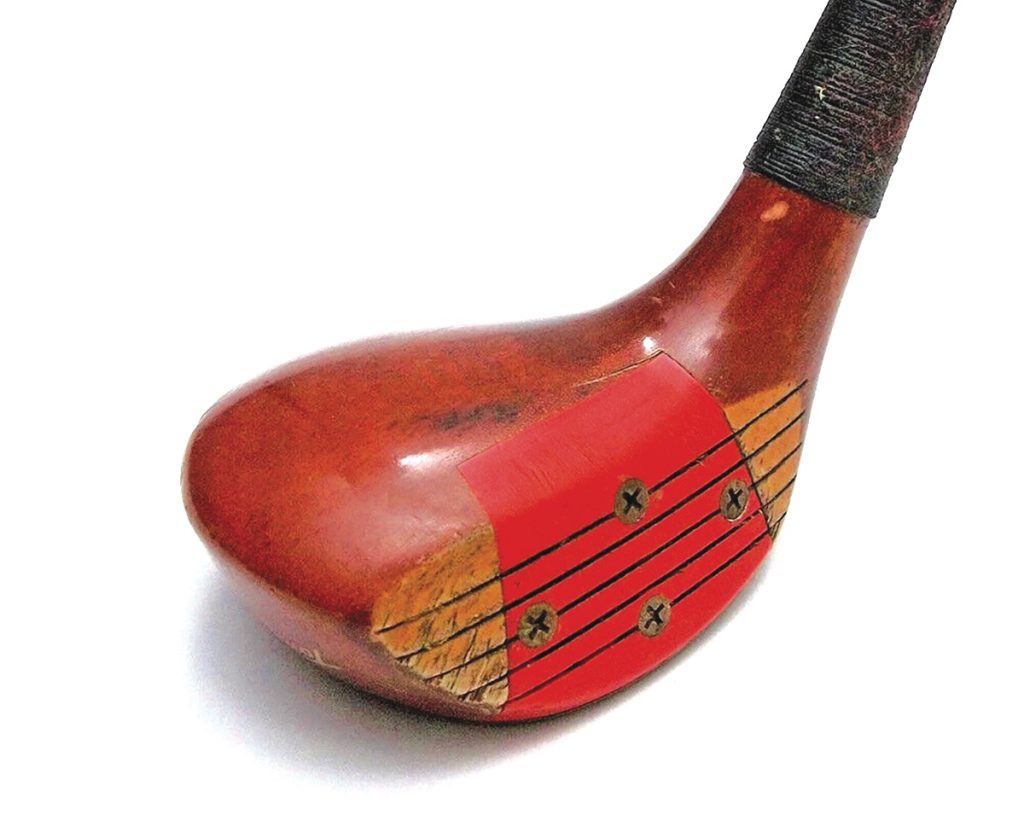

He put a Ping 5-wood into play in the mid-1980s.

“It had a black head and a red, laminated insert,” McGowan says. “I hit it higher with that club than my 4-iron. I’ll never forget at New Orleans, it must have been 1986 or so, I came to a long par-4 or short par-5, I can’t remember which, but there was a bunker all the way in front of the green, and that 5-wood cleared the bunker, landed on the green and stopped on the green. I said, ‘Oh, my God.’ I couldn’t hit that shot with any other club. I hit it high and it landed soft. I took the 1-iron out.”

A few years ago, I was invited to a member-guest tournament at Forest Creek Golf Club in Pinehurst. The competition was five nine-hole matches on the club’s North and South Courses. My host and I played well together that weekend, and we needed to win our match on Saturday afternoon to collect first place in our flight.

The last match was on the back nine of the South Course. We had a 1-up lead on the par-3 17th, our eighth hole of the match. The South Course at Forest Creek, a 1996 Tom Fazio design, is replete with picturesque holes, and this is one of the nicest — an amphitheater setting, downhill, a wide and shallow green with a pond across the front.

The flag was on the left, and the breeze was into our faces. My GPS device measured 182 yards.

I pulled my 5-wood and teed up my ball. I stood behind it and envisioned that crisp contact and a high, right to left ball flight. Believing is seeing, and that’s exactly what I got.

The ball stopped 6 feet from the hole. I made the putt and the match was over.

I won a very nice Scotty Cameron putter that weekend, and I still carry it in my bag. It’s held in high esteem but not quite as high as that smooth and silky 5-wood.