SOUTHWORDS

Holiday Hotline

The Christmas letter that wasn’t

Dear Friends,

In the words of Michael Scott at Dunder Mifflin, over the lips and through the gums, look out stomach, here it comes! Well, it was quite a year. Hottest on record! Yay us! It got off to a great start when the War Department dropped her reckless endangerment charges. As I tried to explain to her at the time, it was only a suggestion. Live and learn.

As you may know, the Carolina Panthers did not win the Super Bowl. Aaaaagain. Turns out they’re worse than their record would indicate. Maybe they should take a page from the convention and visitors bureau in Kentucky that used an infrared laser to send an invitation into deep space attempting to attract extraterrestrials from planets in the TRAPPIST-1 solar system. They can’t do any worse than they do in the NFL draft or making trades. Am I right?

It was a leap year, of course, and that meant the War Department and I had the opportunity to enjoy an additional 24 hours in each other’s company. As it turned out, she was booked on Feb, 29, explaining that it’s not unusual for her to plan years ahead. That’s my girl!

Instead, I read that Finland is the happiest country in the whole wide world, a distinction it has held for seven straight years, which has got to be one of those records that can never be broken — like DiMaggio’s 56-game hitting streak or the Portuguese dog that lived to be 31 — and it wasn’t even in assisted living! So, you tell me, are the Finns sending out deep space laser messages, too? At least they don’t have a football team!

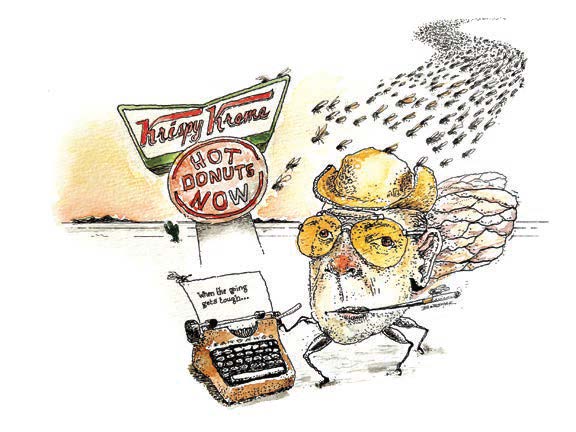

And it goes without saying that we all got fabulous news when McDonald’s announced its intention to sell Krispy Kreme doughnuts fresh daily. This revelation happened around the time cicada broods XIX and XII stuck their little heads out of the ground to rub wings together and party like it was 2024. The last time they did that fandango in the back yard was 221 years ago. Coincidence?

Of course, in June we had the U.S. Open right up the street. Bryson DeChambeau expressed no interest whatsoever in renting our doublewide for the week. Worse luck for him! On the plus side, Scottie Scheffler managed to get through the week without being hauled off in handcuffs. WWGD. What would Gomer do? Citizen’s arrest! Citizen’s arrest!

That’s about when we discovered that, in its latest update, the Oxford English Dictionary added (among other words and expressions) “Chekhov’s gun” to its lexicon. Chekhov, of course, was the Russian playwright who described the literary principle that says unnecessary elements should never be introduced into a story. If you have a gun in the play, someone needs to use it. Which brings me to Rory McIlroy. Ha-ha.

Right after the Open came the Olympics in France. Incroyable! Turns out Simone Biles is tiny. I’m talking Keebler cookie tiny. But that’s OK. As the great Dan Jenkins once said of a famous gymnast, “She can do everything my cat can do.”

I don’t know about you, but the Paris Olympics were a smash hit in our house, and I think it’s safe to say there are some things we can keep in mind for when we host the Open again in 2029. How about those opening ceremonies floating down the Seine? Think Drowning Creek. Am I wrong?

When it comes to mano a mano competition, however, the U.S. Open had nothing on Joey Chestnut, who had to forgo competing for Nathan’s Mustard Belt after he sold his soul to a rival food company. You know what Hunter S. Thompson said, “When the going gets weird, the weird turn pro.” In a counter programing one-on-one match Chestnut downed 83 dogs — not the Portuguese kind, ha-ha — to beat his sworn rival, someone named Kobayashi, who I don’t think has had steady work since The Usual Suspects. Who is Keyser Soze?

It was an election year, and I decided not to run again. Those background checks! Who needs them?

The whole family was here for Thanksgiving, and the War Department made her traditional beef aspic. Lily, the almost 4-year-old, looked at me with those big, wide eyes and said, “Craps.” That’s what she calls me. “Meat Jell-O?” From the mouths of babes!

On to 2025!

Toodles,

The Maury Arties