Star shines in the pumpkin patch

By Jim Moriarty

Photographs by John Gessner

If the Great Pumpkin exists, then Star must be its North Pole.

On the first Saturday of October over 1,000 people — with any luck, way over 1,000 people — will descend on a pumpkin patch like no other. There will be more than 3,000 stunning pieces of blown glass art in a kaleidoscope of colors, dished out in small, medium and large serving portions, sharing just one attribute: their jack-o’-lantern form.

It is the largest annual fundraiser for STARworks, the little nonprofit that dared to believe a massive abandoned textile mill in Star, North Carolina, could represent more than the archeological ruins of a small, rural community’s economic existence. It could be the incubator of its future.

Turns out, blowing glass pumpkins is a bit like turning a double play in baseball. It’s a ballet of speed, timing and finesse, danced to Stevie Ray Vaughan (depending, of course, on who’s in charge of the studio Pandora) at 2,100 degrees. The artist gathers the glass on the heated end of a pipe from an oven in the hot shop holding 1,000 pounds of melted glass. From the moment the glowing ellipsoid is wound onto the pipe it begins to cool, limiting the amount of time the artist has to work with it. No tarrying allowed. “The glass is kind of the viscosity of honey,” says STARwork’s studio director, Joe Grant. “You start turning it — we call that gathering the glass — and from that point forward you have to keep turning. If you stop, gravity is going to take over and drip it off the end of your pipe. Turning becomes like breathing in the studio. You take that gather back to your bench, your workstation, where there’s a number of different hand tools. You cool it evenly on the outside with a wooden block and then trap air in it by blowing and capping the end with your thumb.”

There’s a correct way to get in and out of the bench safely — you are, after all, sashaying around with a stick that’s got a blazing oblong mass of glass well over 1,000 degrees at the end of it. Each workstation is positioned near a “glory hole” — a reheating oven — to keep the glass malleable. “After we come out of the gather,” says Grant, “that’s actually the opportunity we have to put the color on. We roll it in color chips (called frit) and they stick to the surface. You can reheat it and melt them in.” The pumpkin’s ribbed shape is the result of pushing the glass down into a mold, taking it out and blowing into the pipe to inject and trap air.

Meanwhile, a second artist gathers glass on a solid steel rod and, when the first artist has completed the body of the pumpkin, the assistant brings the second gather, presses it onto the top, then stretches it out like a taffy pull. The first artist uses a hand tool to shape the pumpkin’s swirling stem, and clips it off. Voilà. Off to the cooling oven for 12 to 24 hours, if 900 degrees is your idea of cool.

“Most of what we do in there is a team effort,” says Grant, who got a fine arts degree, specializing in glass, from the University of Illinois (where his father taught music), followed by a graduate degree from Virginia Commonwealth University. “You very rarely are working by yourself.” They begin making pumpkins in April but really gear up in August and September, turning out 40 to 60 pieces of glass art in a single day. “People ask, ‘How long does it take to make a pumpkin?’” Grant says. “It might take 20 minutes in the hot shop, but it also takes 15 years of experience and five people that really know what they’re doing to execute it to that degree.”

The pumpkin patch is STARworks, biggest fundraiser but far from alone. There are Hot Glass Cold Beer nights, pairing glass blowing demonstrations with Carolina craft brewers; Firefest, a two-day celebration of fire in both clay and glass arts; a Christmas ornament sale; and on and on. The studio, the gallery, the artist residencies, the apprenticeships, the workshops, the school partnerships, the association with at-risk kids, all of it is just the tip of the pumpkin. STARworks really is a story of abandonment and survival, and it sprang from the imagination of Dr. Nancy Gottovi, an anthropologist by training and the executive director of Central Park NC.

The physical plant of STARworks is a combination of an abandoned school and an abandoned mill. In 1913 the school was the Carolina Collegiate and Agriculture Institute. It morphed into Country Life Academy in the 1920s but didn’t survive the lingering effects of the Great Depression and closed down in ’38. Ultimately, the property became a sprawling textile mill with addition after addition consuming the original building the way an octopus eats a clam. The school has been exposed and refurbished and serves as the entrance to the facility. By the time Russell Hosiery, Fruit of the Loom and the Renfro Corporation were finished with the textile plant, there was nothing left but 140,000 square feet of vast, dilapidated emptiness and a town that didn’t seem to have a reason to exist.

“The cultural impact, the economic impact, the infrastructure impact of the loss of these manufacturers has created incredible problems for really small rural communities like this,” says Gottovi of Star. “The United States is full of them. What is going to be the reason for being for these communities? These mills are not likely to come back. So, what are they going to do?”

A local businessman who wanted part of the old mill bought the whole shebang and donated what he couldn’t use to Gottovi’s nonprofit. Great. What’s a nonprofit going to do with 140,000 square feet of leaky roofs and bad wiring, build the world’s largest indoor racquetball facility? First, you study. Gottovi interviewed every age group in Star. The children could imagine the town being Disney World. Kids can imagine anything. The nursing home set could remember Star as it once was, before the mills. The middle-aged folks could only imagine what was gone and never would be again. “I felt enormous pressure to start something,” says Gottovi. “To say the local community was very skeptical about what we were going to do in here is an understatement of vast proportions — and I would have said the same thing. We had killed countless trees producing white papers talking about the importance of small businesses that were related to the natural and cultural assets of the area rather than just attracting companies to come in for cheap land, cheap labor, extracting it all and leaving. I really felt like we needed to focus on businesses that had some kind of rootedness in the community.”

The foundation of STARworks was built on clay. “What are goods and services that are needed in the community that have to be imported?” Gottovi says. “So, we’ve got like 100 pottery shops in Seagrove and they’re all shipping in clay and buying it elsewhere. That’s a business opportunity.” They invested $500 and made $600. Then $600 and made $700. Gottovi met, and managed to convince a Japanese potter, Takuro Shibata, to run it. Shibata has a chemical engineering degree from Doshisha University. His wife, Hitomi, is also a potter. They had a studio in Shigaraki, the Seagrove of Japan. They were attending a program in Virginia and Gottovi convinced them to visit. They arrived by Greyhound bus and, amazingly, agreed to return.

“We had tremendous support from the ceramic community,” says Gottovi. “Now STARworks ceramic is widely touted as maybe the best clay sold in the United States. It’s a small boutique clay business. Our goal is not to make clay for everybody but to make clay for people who really care about the material.” And — and this is important — at a profit. They weren’t just artsy-craftsy, they made money.

“So, OK, we’ve got potters coming here to buy clay,” says Gottovi. “I was also looking for businesses that would be attractive to tourists. And, if it’s something you can export, even better, right? I thought glass.”

Which was odd since Gottovi knew absolutely nothing about it. Zilch. Zero. Nada. “I was so ignorant,” she says.

So she wrote a grant. It got funded. “Oh, my God,” says she. “I’ve got to build a glass studio.” That was January 2006.

Gottovi picked up the phone. She called everyone who knew anything at all about glass blowing studios pleading, begging, for advice. Everyone’s response was the same. The person you really need to talk to is Eddie Bernard in New Orleans.

There was one tiny — well, not so tiny — problem. Hurricane Katrina crushed the Gulf Coast in August 2005. Bernard’s shop, Conti Glass, was at 3924 Conti Street under 7 feet of water. He was wiped out. When they were finally able to connect on the phone, Bernard agreed to visit Star on his way back from Pittsburgh, where he was attending the Glass Art Society conference. He and his wife, Angela, took a tour of the building and spent the night at the Star Hotel.

“The ceiling had collapsed back there,” says Gottovi of the proposed location of her glass studio. “It was pouring rain inside the building. We were standing there with umbrellas and Bic lighters and flashlights because the electrical system was completely fried. I look back on it now and I think, I’m talking to these people who have been flooded out in New Orleans and we’re standing there with rain pouring down inside the building and I’m going on and on about, ‘Wouldn’t this make a great glass studio?’”

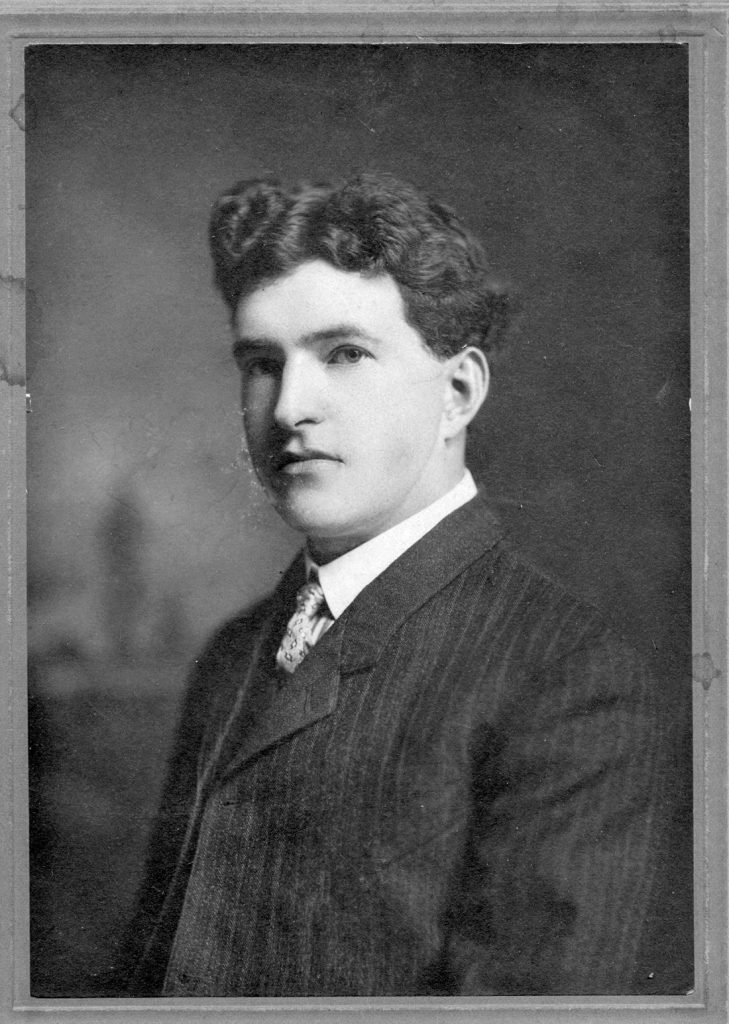

Perceptions, however, can be relative. “It’s kind of wild,” says Bernard, 43 and a graduate of Rochester Institute of Technology. “Somehow, it seemed totally fine. We knew it could be habitable; that’s because of the different places we’d run our business in New Orleans. We were always in a real cheap kind of rough neighborhood with leaks and holes in the walls and raccoons living in buildings. And then we had Katrina. We didn’t have electricity for eight months. When we saw Star, we heard the town was devastated but they still had electricity, they had mail delivery, they had schools, a library. It looked fine to us.”

Plus, Bernard’s business manufacturing glass blowing equipment, now called Wet Dog Glass (a nickname he picked up wading through water to get to school after being flooded out as a 10th-grader in his native Lafayette, Louisiana) needed to be up and running because they were in line for a job setting up the glass studio for Temple University’s Tyler School of Art. “At the time, it was going to be the biggest contract we’d ever done,” says Bernard. “We knew we needed to get our business set up again to be able to handle it if we got it. And we had to prove to them we were capable again, as well.” The contract came through and now Wet Dog Glass is one of the world’s premier U.S. manufacturers of glass blowing equipment and sells into 15 to 20 different countries, including China.

But, of course, Gottovi still needed to build that studio and, after she put on a new roof and did some wiring to make the building usable for Bernard, there wasn’t much grant money left.

“Eddie comes into my office one day and says, ‘It’s time to talk about your studio,’” says Gottovi. She showed him the budget. It doesn’t sniff being enough, even for a wet dog. Bernard comes back the next day with an offer. He’ll build the studio for the money she has left if he can use it for R&D, equipment prototypes and whatnot. “I said, ‘Let me get this straight. You’ll build us this state of the art studio for this ridiculous amount of money and all I have to do is let you come in and make improvements periodically?’ Yeah, I can do that,” says Gottovi

Instant (well maybe not so instant) pumpkin patch.

Now there’s a clay business, a manufacturing business, a glass blowing studio, a meeting space and a design studio, all under the umbrella of STARworks. The ultimate goal, of course, is far broader. Where once there was a rural community circling the drain after its sole economic driver pulled the plug, now there is a realistic chance to create a virtuous circle from the ground up with small businesses. “The 12 years that we’ve been working on this project, I guess my hope has always been that people would see what we’re doing here, would see our success and would say, ‘I think I’ll start a coffee shop in downtown Star.’ I’m waiting on the tipping point,” says Gottovi.

Bernard, who is in his second term as Star’s town commissioner, has purchased two old buildings in the downtown and has begun renovating them. Though he doesn’t ride himself, he started Star Trek Bike Ride, a cycling event through Montgomery County that raises money for a family crisis center. He’s done projects in the park, including horseshoe pits and playground equipment. “When you contribute something to your community, you don’t lose it,” he says. “It’s just that more people get to have it.”

Bernard doesn’t produce much glass art of his own anymore. He’s mastered another skill, doing two or three magic shows a year as fundraisers for the Craft Artists Relief Fund supporting artists wiped out by storms like Katrina, Harvey or Irma. “I have someone pick a card,” says Bernard. “We’ll put a white tile inside of a bottle while the bottle is 1,800 degrees. I read a magic spell, then all of a sudden, the white tile that’s in the bottle turns into the card that they picked.”

Sometimes magic happens just like that. Sometimes it’s decades in the making. PS

Jim Moriarty is senior editor of PineStraw and can be reached at jjmpinestraw@gmail.com.