Uncle Bert, The Armless Elocutionist

By Scott Sheffield

Albert Livingston Stevens was technically my great-great-uncle. But to me, he was simply Uncle Bert. From the first time I could remember family gatherings for Thanksgiving or Christmas, Uncle Bert and his wife, my Aunt Mabel, were there. I remember every Christmas, they would give me two silver dollars in a small white box with a cotton lining. For the entire time I knew Uncle Bert and Aunt Mabel, they lived in Southern Pines, and when I addressed my thank you notes to them, I always thought, as a boy growing up in plain old northern Virginia, how wonderful a place called Southern Pines must be.

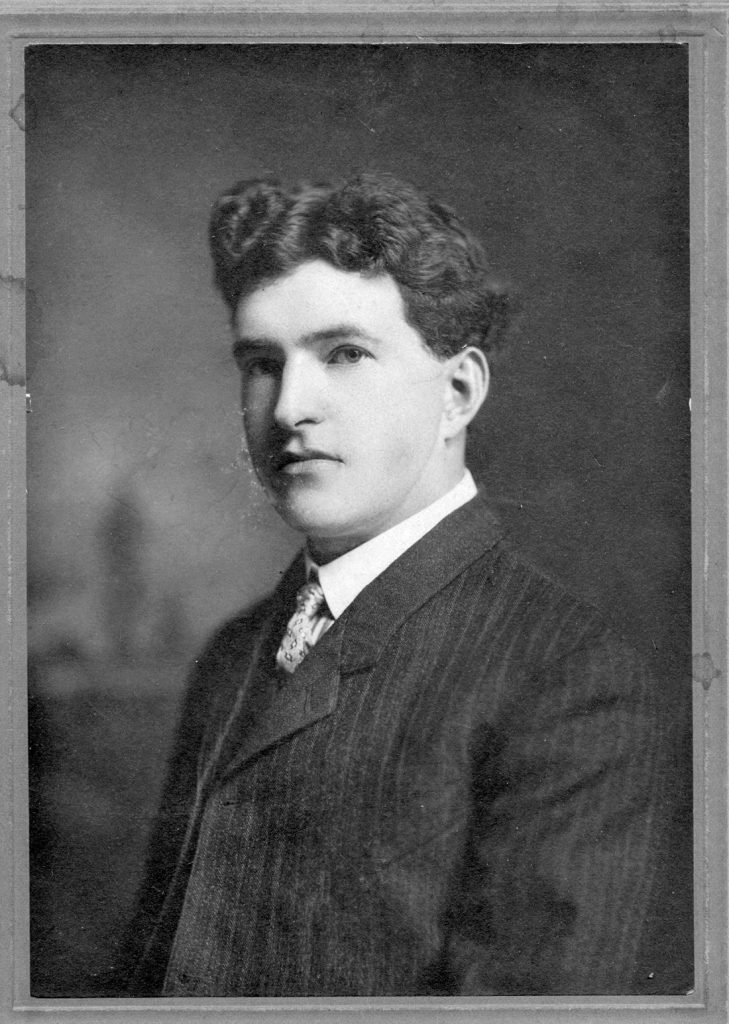

Uncle Bert was already 72 years old when I was born, and by the time I first really noticed him — at the age of 4 or 5 — he was the oldest person I had ever seen. I didn’t quite know what to make of him. He had a wild shock of white hair on top of his head, large brown spots on his face and leathery cheeks etched by deep, wavy lines. But it wasn’t his face or his hair that fascinated me. It was something else.

I never remember seeing Uncle Bert dressed in any attire less formal than a coat and tie, and usually a suit. His appearance in those suits was different from any of the other men in the family who were similarly attired. The right sleeve of his jacket never clothed an arm or revealed a hand. The cuff was always neatly tucked into the waist pocket. A stiff, unmoving black glove extended from the left cuff of his jacket. The glove concealed a wooden prosthetic hand, no doubt state-of-the-art for the 1950s, but it was both scary and intriguing to me at the same time.

Albert, or “Bertie,” as he was known in his younger days, was born on May 15, 1874, lost his father at the age of 5 and was completely orphaned at the age of 10, shuffled from one relative to another. At 14, Bertie landed a job, his first, in the wire and cable department of the Edison Machine Works in his hometown of Schenectady, New York. He liked the job and especially enjoyed those occasions when he would see Thomas Edison who, I later discovered, he described as “a kindly man about whom clung an aura of fame.”

Only weeks into his new job, walking home from work on the New York Central tracks, a common path used by the plant’s workers, he was struck from behind by a locomotive. He fell with his arms outstretched, and as the engine passed over him, it severed his right arm at the shoulder and his left just below the elbow. Miraculously, he survived. Damage to his right shoulder was so severe that it was just sewn up and left to heal. However, his left arm was a different story. Because the engine’s wheels had struck it below the elbow, the doctors were eventually able to fit him with an artificial arm and hand. Instead of having to be fed, he learned how to feed himself. He likewise learned to perform much of his daily routine without assistance, with the obvious exception of tasks like buttoning a shirt or tying his shoes.

Uncle Bert had no intention of leading a homebound life. Funds were raised through civic organizations to pay his hospital bills and fit him with his artificial limb. He continued his education, emphasizing music, and eventually studied at Claverack College, an institution that closed in 1902 but was once attended by Martin Van Buren, the eighth president of the United States. After visiting a brother in Tennessee, Uncle Bert decided to go into “show business,” forming his own vaudeville troupe. Among our family’s memorabilia is a copy of one of the posters advertising the 1896-97 season of the Albert L. Stevens Big Five, on which he is billed as “The Armless Elocutionist, Vocalist, Clog and Jig Dancer.” In addition to the poster, we have a pair of Uncle Bert’s tap shoes. Other members of the troupe were billed as “Acrobats, Contortionists, Tumblers, High Kickers and Masters of Strength.” Another was described as “Virginia’s Great Violin, Guitar and Banjo Soloist.” Still another performed “Gags, Sidewalk Talk, Songs and Dances” as the “Witty Irish Character.” They traveled at first by horse and buggy and later with a wagon and team. It was a show date that brought him to North Carolina for the first time.

He returned to Schenectady in 1901, where the Edison Company had a job waiting for him. Next, he took a turn at selling, which again brought him to North Carolina, then back to Schenectady, where he started a newsroom business. After he and Aunt Mabel married in 1905, employing a strategy of leasing, then buying, as finances would allow, he gradually became his own version of Conrad Hilton, owning five hotels and apartment houses, including The Livingston, The Myderse, Bachelors Hall, The Seneca and Hotel Foster. He served at least one term as the Fourth Ward supervisor, elected on the Citizens Party ticket. In 1914, he began driving his own automobile, a modified Model T Ford. From April 11 to Dec. 1, he put over 10,000 miles on his new car, including a trip to Washington, D.C. The following year he and Aunt Mable, accompanied by another couple, set out on a transcontinental trip to the Panama-Pacific Exposition in San Francisco.

“For a long time I thought I could have a car fixed so I could handle it,” he was quoted as saying in the March 1915 issue of Ford Times. “But all my friends, and especially my wife, were very much opposed to my trying to drive. They predicted all kinds of accidents if I ever attempted such a thing.

“I had the emergency brake lever changed so I can operate it with my foot. I have a foot accelerator to feed the gas; electric lights which I turn on or off with my foot; an electric horn which I blow by pushing a button with the side of my knee; spark lever bent so I can advance or retard the spark with my knee; and I crank the engine with my foot. I have a steel U-shaped attachment which clamps on the side of the steering wheel. I place my arm in that and steer very easily. I drive just as steadily and well as most people with two hands and arms, and I think a great deal better than some.”

I had heard the story about how Uncle Bert had outfitted a car to accommodate his disabilities and the trip to California many times, each retelling evoking no less awe than the last. While the actual route of the trip is unknown, a little research led me to believe that the most likely one began on the National Old Trail Road. The newest “highway” of the day was The Lincoln Highway from New York to San Francisco, but the Aug. 21, 1915 Wichita Beacon Journal (accounts of Uncle Bert’s journey popped up in stories ranging from Salt Lake City to Atlanta to Detroit) mentioned him passing through that city on his way west, putting him on the Old Trail. From Kansas he likely took the Leavenworth and Pike’s Peak Express or the Butterfield Overland to Denver where he could join up with the Lincoln Highway to reach San Francisco. In an Aug. 15, 1915 story from the Los Angeles Tribune he identifies The Lincoln as his route west. “When he told his friends that he was going to take his machine across the continent and traverse the mountains and the deserts, they laughed at him,” the L.A. Tribune went on to say.

From San Francisco he went south to Los Angeles and San Diego, then east on the old Santa Fe Trail to eventually rejoin the Old Trail. A driver traversing any of these roads would normally encounter roadbeds fabricated of dirt, sand and gravel, only occasionally finding a stretch of macadam. Oddly enough there was a section from Wheeling, West Virginia, to Columbus, Ohio, that consisted of brick. However, there was also a stretch through the Rocky Mountains that was devoid of any paving material other than what occurred naturally. An official road guide, published a year after Uncle Bert’s trip, described a journey on The Lincoln Highway as “something of a sporting proposition.” Camping equipment was recommended west of Omaha, Nebraska. Add the fact that filling stations were few and far between and a coast-to-coast trip in those days was a daunting undertaking, its completion simply amazing, especially for a driver without arms.

To fund this project, Uncle Bert apparently solicited sponsors, automotive-related companies such as Kelly-Springfield tires and Red Crown gasoline, for the car was emblazoned front to back with decals. Camping out and — as Uncle Bert suggested in one story — selling postal cards also helped defray the cost. Captions on the back of one of the surviving photos identifies it has having had been taken at Universal City, then a new location for the nascent film industry. Why he stopped there is as unknown as the route, but it may have been that during his vaudeville days, he met or associated with some show folk who went on to appear in movies, and he was simply renewing acquaintances.

This was all part of family history, and so, unfortunately, was what happened at the height of his success. It was at the end of the Roaring 20s and optimism in the country was at an all-time high. Then, the stock market crashed and along with it the national economy. The resulting Great Depression saw billions of dollars in wealth and income evaporate literally overnight. Uncle Bert’s fortunes were no different. He lost everything, all his holdings, except for a resort on Schroon Lake in the Adirondacks, which he had given to Aunt Mabel as a birthday gift. With this property, he began a new upward climb, gradually adding more cottages and a store to the resort.

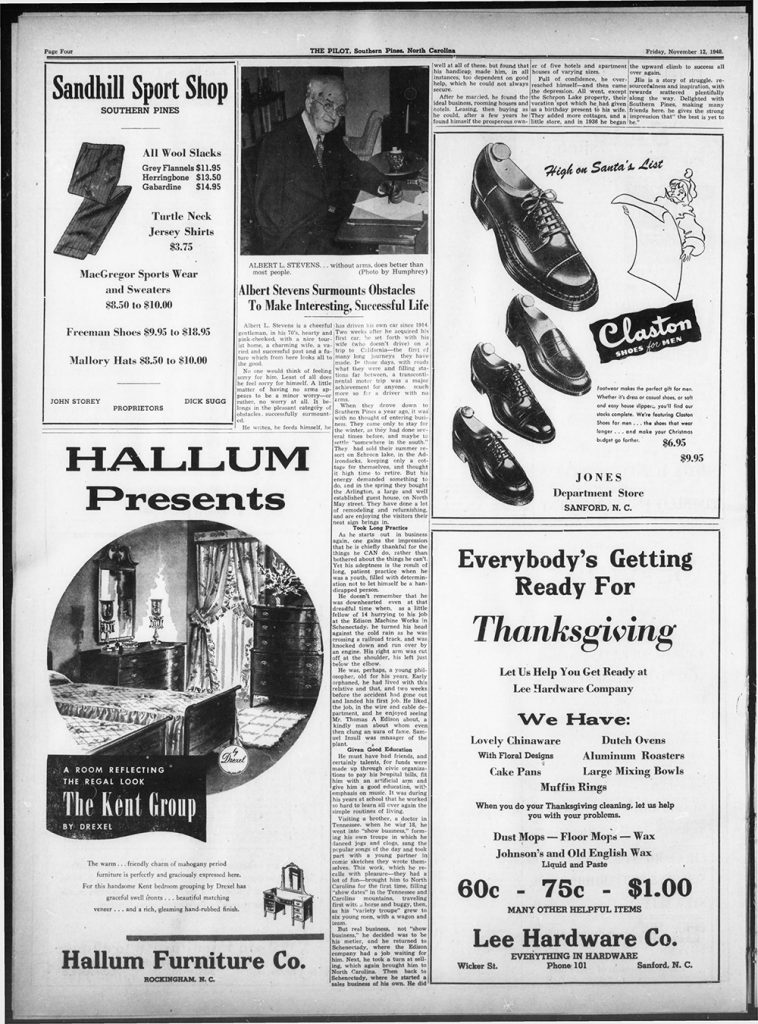

A little over a year ago, going through a box of family memorabilia with my brother, Steve, in Florida, we discovered a photostat of an article clipped from an old newspaper, The Pilot. Much of the information in it was familiar to us, but some was new. At the time, I’d lived in Pinehurst for 12 years. That such a story would appear was unsurprising, since he and Mabel lived in Southern Pines in their later years. The article, however, was incomplete, ending in mid-sentence. There was no byline and no date. My only hint as to the age of the story was that the accompanying picture showed him as I remembered him when I was very young and mentioned that he was in his 70s.

Since my uncle had been born in 1874, the article must have appeared in the paper between 1944 and 1954. The volumes of those years were archived at the Southern Pines Library. The bindings were in various stages of decay, but all the years I was interested in were there. From the portion of the article that I already had, it was apparent the author’s interest in Uncle Bert was his recent decision to buy the Arlington, described in the article as “a large and well established guest house on North May Street.” The building at 440 N. May is there today.

I decided to begin my search for the original article with the year I was born, 1946. I didn’t find it there, nor was it in 1947. Reading articles from 70 years ago, the news of the day and the news makers, the ads and the entertainment notices, provided a whole new appreciation for this place and those times. Near the end of the 1948 volume, I saw it. I was initially surprised and relieved that the page containing the article was there at all because not every page was. The condition was much better than the copy my photostat apparently came from. The date of the article was Nov. 12, 1948.

During their years in New York, the article relates, Uncle Bert and Aunt Mabel had wintered in the Sandhills many times, and it was only with that thought in mind that they returned here again that year. However, they had sold their resort in New York and Uncle Bert had decided that after his long and eventful career, it was time to retire, with an eye toward settling someplace in the South. “When they drove down to Southern Pines a year ago, it was with no thought of entering business,” says the story. But apparently, Uncle Bert didn’t have it in him to fully retire. They bought the guesthouse and settled here.

The article, detailing his life, concludes, “His is a story of struggle, resourcefulness and inspiration with rewards scattered plentifully along the way. Delighted with Southern Pines, making many friends here, he gives the strong impression that ‘the best is yet to be.’”

After 56 years of marriage, Aunt Mabel died in 1961. Following a couple of years at St. Joseph of the Pines, Uncle Bert passed away at the ripe old age of 89. He lies in Mount Hope Cemetery in the town he loved so much. PS

Scott Sheffield moved to the Sandhills from Northern Virginia in 2004. He is retired from the federal government, where he served as director of the headquarters contracting office for the U.S. Department of Energy in Washington, D.C.