By Jim Moriarty

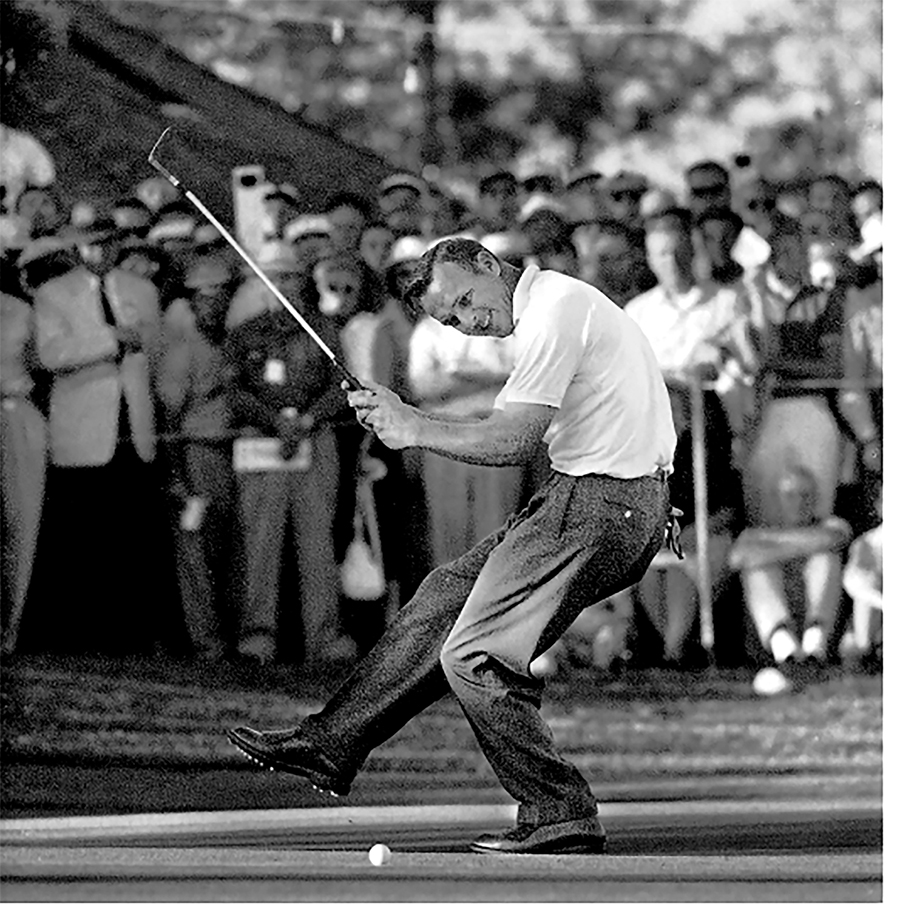

Feature Photograph: Payne Stewart during the fourth round of the 1999 U.S. Open Championship held at Pinehurst Resort and Country Club No. 2 Course in Pinehurst, N.C., Sunday, June 20, 1999. (USGA/John Mummert)

Springfield is a small town on the Ozark Plateau in a state that was red before anyone thought about color-coding them. It’s the third-biggest city in Missouri, but if it was in California, it would barely crack the top 30. The Trail of Tears passed through Springfield on what was once called the Military Road. The North and the South fought over it, and in 1865, three months after Lee surrendered to Grant, “Wild Bill” Hickok shot a man dead on its streets over a pocket watch.

In the post-World War II craze over a new medium, television, Springfield took country music nationwide with The Ozark Jubilee. A year later Chris Schenkel and Bud Palmer debuted on CBS at the Masters. Three men born in Springfield have won major golf championships, and two of them are in the World Golf Hall of Fame. St. Andrews might be the only small city east of Fort Worth to equal its output.

If Payne Stewart wasn’t in uniform, knickers custom made from bolts of Italian cloth, silk stockings, gold- or silver-tipped spiked shoes and an ivy cap in the Ben Hogan style, he was as unrecognizable in public as if a Maserati had been stripped down to a Dodge Dart. “He comes off as this real urbane, Great Gatsby type of guy,” said his longtime swing coach, Chuck Cook, “but, really, he was a Missouri mule. Just a country boy from Springfield.”

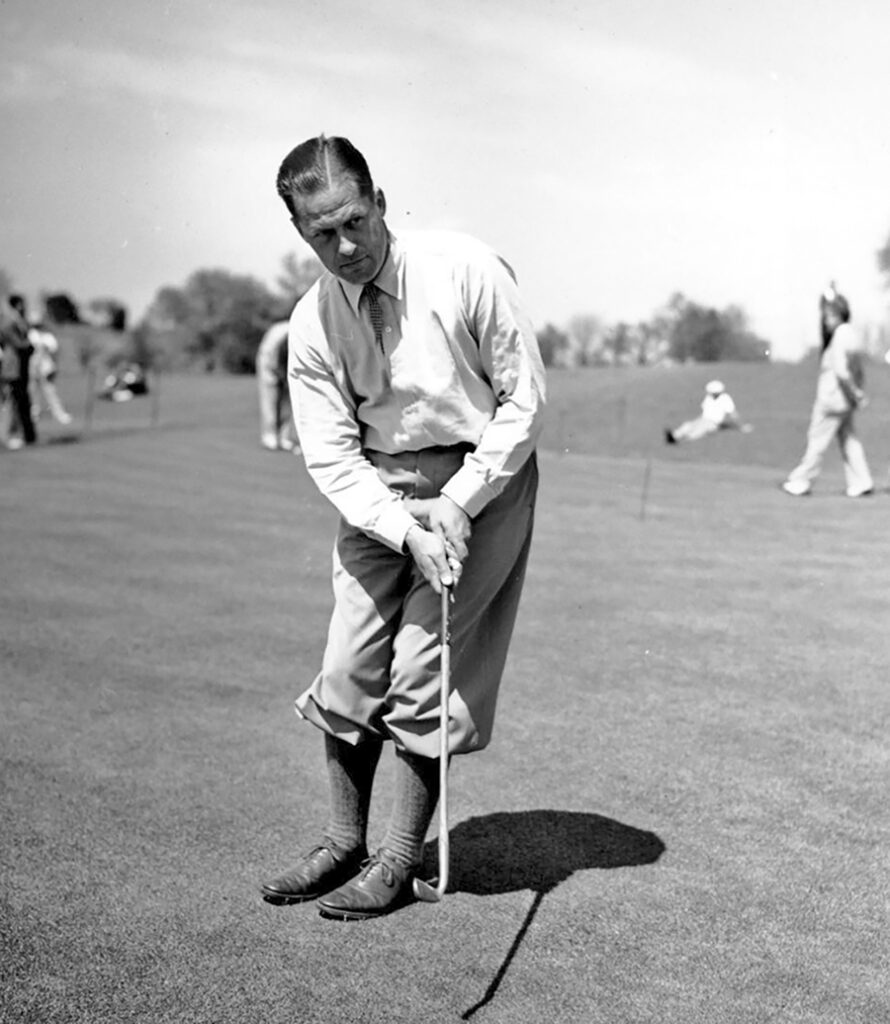

Back in the heyday of newspapers, when a sports star needed a nickname the way a clipper ship needs wind, Stewart was preceded as a major champion by Horton Smith, the Missouri Rover, and Herman Keiser, the Missouri Mortician, who won three Masters between them. While Smith was eventually associated more closely with the Detroit Golf Club and Keiser with Firestone Country Club in Akron, for a time they were both at Hickory Hills Country Club in Springfield, where Keiser worked as Smith’s shop assistant.

Hickory Hills is where Stewart learned to play, as aware of the champions who came before him as he was of characters like Ky Laffoon, who favored sky blue sweaters and socks as yellow as two daffodils, and once hustled the young Stewart on its chipping green. While Springfield’s other major champions both made their reputations in the Masters, Augusta was the big moment Stewart enjoyed least. Deeply patriotic, the National Open was above all others to him. At his father, Bill’s, insistence, he always signed his U.S. Open entry with his full name, William Payne Stewart. He didn’t like the Masters because he thought the little people were treated shabbily there, particularly the caddies.

“He really felt uncomfortable,” said Cook. “When we would go to Augusta, we’d always eat in the employee dining room instead of out front with everybody else.” Before ugly false teeth became a Halloween cliché available at every party store in America, Stewart had a set custom made by a Springfield dentist, Dr. Kurt H’Doubler. He stuck them in his mouth frequently for effect, but took particular pleasure in wearing them in the par-3 contest at the Masters.

Even if he’d lived in the age of nicknames, Stewart was too complicated for that kind of lazy gimmick. He could be arrogant and thoughtless or generous and compassionate, sometimes in the same sentence. He was a devoted practitioner of the sporting jibe, what’s mostly described now as trash talking, though it didn’t always come in the form of talk. “He was an awful fan,” said John Cook, a former U.S. Amateur champion who, like Stewart, lived in Orlando, Florida. “Just awful. I’d pick him up and we’d go to the Magic games. He’d be yelling at somebody the minute he got in the arena.”

Stewart’s seats for the NBA games were four rows behind the Magic bench, and he took great delight in ceaselessly taunting the head coach at the time, Matt Goukas. “Poor old Matty,” said Dr. Dick Coop, Stewart’s sports psychologist. “Payne just lit him up every night.” After only one season Stewart’s seats were moved, not just from behind the bench, but to the other side of the arena.

The canvas for Stewart’s needlework included golf, and he didn’t care whom he skewered. “Jack Nicklaus. Arnold Palmer. It did not matter,” said his longtime caddie, Mike Hicks. “And you know what? A lot of guys didn’t like it. Some guys didn’t mind, and if they didn’t mind, they liked Payne. But if they minded it, they didn’t like him. If they all say they liked him, they’re lying because he was tough, man. He would needle you, and he would go overboard with it. He could take it, too. But he’d get under your skin if you let him.”

Once, when Stewart was visiting Jim Morris, an old family friend in LaQuinta, California, they arranged a money game with Donald Trump. The wealthy developer was five minutes late to the first tee, but Morris and Stewart didn’t wait for him. By the time Trump pulled up in his golf cart, they were ahead on the first fairway. Stewart yelled back at him, “Trump, this ain’t one of them corporate meetings. It’s 1 o’clock and you’re either here or you ain’t here.”

Coop, at the time a faculty member at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, began working with Stewart the same year Hicks became his caddie, 1988. “The first day he came to see me,” Coop said, “I told him what I’d heard about him very bluntly, very forthrightly. He calls Tracey (his wife) and she says, ‘What did he say?’ And Payne said, ‘Well, he told me I was arrogant, cocky, brash, insensitive, etc.’ She said, ‘What did you say?’ Payne said, ‘Well, I told him he was probably right.’ We started off that way.”

Stewart grew up in a one-story house on Link Street with three women and a traveling salesman, which could be a joke if it wasn’t true. His father, Bill, sold mattresses and box springs and was often on the road, leaving Payne with his sisters, Susan and Lora, and his mother, Bee, who was as rare a species in Springfield as a snow leopard: a staunch Democrat. In election season Bee filled the yard with political placards like dandelions.

“He had a lot of girl in him,” said Cook. “Ironed his own clothes. He loved to cook. He liked to dress up. Then, when he’d be with the boys, he’d be about as macho as anybody. He wasn’t afraid to try to outdrink you or outplay you or anything else.” Stewart made French toast on a local Springfield cooking show when he was 3 and reveled in making a breakfast of waffles and pancakes for his own children, Aaron and Chelsea, whenever he wasn’t traveling to play golf.

In the late 1970s, if you didn’t make it through the PGA Tour’s soulless meat grinder that was its qualifying tournament, your playing options were few. One was to go to Florida and join a mini-tour, where the prize money was the aggregate of the entry fees, less what the tour organizer skimmed off the top for himself. If they were unscrupulous, that included the prize money too. You were essentially playing for your own cash, plus everyone else’s. It was a hard lesson for even the best young former college star, being picked clean by local legends with garage-band swings who knew every blemish and blade of grass on the undistinguished courses they played. The other most commonly chosen option was the Far East, and that was where Stewart found himself after graduating from Southern Methodist University and failing to get his tour card.

Two of his traveling buddies in Asia were the Anton twins, Terry and Tom, who had played at the University of Florida. Because of the springy way they stepped, with their heels off the ground, Stewart called them Tip Toe I and Tip Toe II. While Stewart’s confidence in his golf game crossed the border of cockiness without clearing customs, it was actually more a case of the sum being greater than its parts. He swept the club back with a lag reminiscent of Bobby Jones and the hickory-shaft era. His tempo looked as effortless as the human eye wandering through a Cézanne still life, but he was neither a great driver of the ball nor the best iron player nor the best putter. In his prime, though, when it came to the short shots around the green, inside 75 yards or so, he had no peer. Some of that was learned from the hustlers in Springfield, but some of it was imported from Asia.

“We had a tremendous admiration for the Asian players’ short games. All of us learned,” said Tom Anton. “It was a great training ground. They showed us techniques around the greens, out of the bunkers, shots we’d never seen before. We’d bomb it by them but from 100 yards in, they were magicians.”

Besides a short game, the other significant acquisition Stewart made was in Kuala Lumpur when he met a 20-year-old Australian woman named Tracey Ferguson, who was at one time a draftsperson employed by Greg Norman’s father at Mount Isa Mines. He fell in love with her the moment he saw her in a string bikini. Stewart succeeded in making it through the PGA Tour’s spring qualifying school in June ’81, the same month David Graham played a near-flawless final round at Merion Golf Club to become the first Australian to win the U.S. Open. He and Tracey were married that November.

While Stewart won twice in Asia and again at the ’82 Quad Cities Open, the only tour tournament his father saw him win, his early reputation was that of a player who could come close but not finish it off at the end. He lost playoffs in ’84, ’85, ’86 and ’88. He compiled so many seconds his nickname was Avis. When he finally won the ’87 Hertz Bay Hill Classic, he donated the winner’s check to charity in honor of his father, who had passed away two years before from cancer.

After finishing in a tie for 24th in the Masters in ’89, Stewart won the next week at the Harbour Town Golf Links, an event played on a classic South Carolina low country course designed by architect Pete Dye and known for the quality of its champions, a list that included Palmer and Nicklaus, Johnny Miller and Tom Watson. Stewart would become the first player to successfully defend that title. It was in August ’89 at a Chicago suburban course named for an insurance company, Kemper Lakes, where Stewart captured his first major championship in typically controversial style.

By that time, it felt like most of the big stuff had already been done. Nick Faldo won the first of his three Masters on the second hole of sudden death when Scott Hoch agonized over, and then missed, a 2-foot sidehill wobbler on Augusta National’s 10th. The big story of the year was Curtis Strange, who took advantage of Tom Kite’s final-round 78 to become the first player since Ben Hogan to win back-to-back National Opens. “Move over, Ben,” said Strange. In the wake of the Open Championship, all the conversation was about how star-crossed Greg Norman let yet another major championship elude him. Mark Calcavecchia won at Royal Troon, defeating Australians Wayne Grady and Norman, who couldn’t even post a score in the four-hole aggregate playoff.

Stewart had played progressively better in each of the 1989 majors, going into the final round at Royal Troon just two shots behind Grady, one better than Calcavecchia. After closing with a 74, however, he was nothing more than an afterthought going into the PGA at what would become storm-ravaged Kemper Lakes — especially since he’d shot 75-76 in Memphis the weekend before. It was Mike Reid, a product of Brigham Young University, slender as a cattail stalk whose reverse-C finish was so pronounced it made grown men wince, who took command almost from the outset. Reid, nicknamed “Radar” because his drives, though short, tracked the center of what seemed like every fairway, was tied for the lead after the first round and alone at the top after 36 and 54 holes. Stewart, dressed as he did every Sunday in the colors of the local National Football League team, this time the Bears, went into the final round a full six shots off the pace.

A five-birdie back nine of 31 pulled Stewart within two of Reid’s lead and gave him reason to stick around. In April Reid had led the Masters after 13 holes on Sunday and didn’t finish well, but that disappointment was nothing compared to what happened at Kemper Lakes. He bogeyed the 16th to lose half his lead, and then smothered a lob shot from just off the 17th green and double-bogeyed, shockingly dropping a shot behind. Stewart couldn’t be still in the scoring area, pacing back and forth, even mugging for the camera. Reid had a chance to birdie the 18th to tie him but missed a 7-footer.

Stewart’s glee was demonstrable. He emerged from the scoring tent slapping high fives with anyone he saw, and that, unfortunately, included Reid as he came off the course. Stewart’s pleasure seemed blissfully ignorant of Reid’s pain. “I’m 32. I hadn’t won a major, and everybody all over the world is always asking me why,” he said. “They did the same thing to Curtis and look what happened. He won back-to-back U.S. Opens.” The contrast of Stewart’s self-satisfaction and the unselfconscious tears of the mild-mannered Reid was so stark that what should have been the affirmation of the skill and ability Stewart always believed he possessed became, instead, the coast-to-coast confirmation of his most unpleasant character traits.

Very soon after Coop began working with Stewart, he suspected his new client had attention deficit disorder and sent him to a clinician for a proper diagnosis. “I’ve got to give him tremendous credit,” said Coop. “When he found out what he had, he talked to people about it. He didn’t hide it. God gave him tremendous rhythm and tempo and neuromuscular skills, but God didn’t give him concentration.”

The knowledge of the condition led Coop and Cook to devise practice sessions tailored for someone whose ability to concentrate was, at times, tenuous. It wasn’t always, though. “With the ADD, the U.S. Open was always set up so hard that he was able to focus during the tournament,” said Cook. “The rough was so tough and greens were so fast and hard, it created a lot of focus for him that he didn’t have in a run-of-the-mill tournament.”

In March ’91 Stewart was wearing a brace to stabilize a herniated disk in his neck that had caused him to lose strength in his left arm. Reduced to nothing more than a spectator in his own backyard at Bay Hill during Arnold Palmer’s tournament, he was out for 10 weeks and unable to play in the Masters. An exercise regimen helped rehabilitate the neck, but Stewart would struggle the rest of his career with three degenerative disks in his lower back. He played at Harbour Town the week after Augusta, tied for fourth, and took aim on his most prized goal, the U.S. Open at Hazeltine CC, outside Minneapolis.

The U.S. Open had been at Hazeltine on one previous occasion, when the Englishman Tony Jacklin won in 1970, and the layout of architect Robert Trent Jones was mocked as if it had been drawn up by a 4-year-old with finger paints. After the ’70 Open, Jones made some changes, augmented later by his youngest son, Rees, a second-generation golf course architect like his older brother, Bobby.

By the time the U.S. Open returned to Minnesota, it had a trio of finishing holes as tough as any in golf, holes that would cost Scott Simpson a second national championship. Simpson, who would later become almost as well known for being actor Bill Murray’s patient partner in the annual Pebble Beach pro-am started by Bing Crosby, birdied the 14th, 15th and 16th holes in the ’87 U.S. Open at Olympic Club outside San Francisco to beat eight-time major champion and local favorite Tom Watson, who had attended Stanford University, just up the 101 Freeway.

Simpson, a University of Southern California product himself, finished in the top 10 in the next two U.S. Opens (the ones won by Curtis Strange) to earn a reputation as a dependable Open player. He had an unusual action. At address he’d slowly lower his upper body toward the ball and then rise up as he took the club back to the top. Though their swings were as similar as a Van Gogh and a mechanical drawing, Stewart and Simpson had at least one trait in common: Neither was given to making the big mistake. In a U.S. Open brilliance has far less to do with swashbuckling shotmaking than it does the ability to avoid calamity, shot-by-shot, hole-by-hole, until you’ve simply outlasted your peers. It’s about as glamorous as being stuck with the check.

Just like at Kemper Lakes two years before, a violent summer thunderstorm hit Hazeltine, but this was far worse than just an interruption in play. A darkening sky filled with electricity halted the first round just after 1 o’clock, and six men took shelter underneath the branches of a small willow tree 30 yards or so from the 11th tee. Two flashes of lightning knocked all six to the ground. William Faddell, who was not even a golf fan but who had been given the tickets by his father, died of cardiac arrest. Two months later, at the PGA Championship at Crooked Stick outside Indianapolis, another spectator, Thomas Weaver, was killed by lightning in the parking lot. The confluence of tragic events led to golf’s organizers forever changing the way they treated hazardous weather.

When play resumed, the rain-softened course gave up some good scores, including Stewart’s opening 67, which tied him with Nolan Henke, a Battle Creek, Michigan, native who would just as soon have been fishing as leading the U.S. Open. By the end of three rounds Stewart and Simpson had managed to separate themselves from the field by three shots. For almost all of Sunday Simpson was in firm control. Almost is the operative word. He reached the final three holes with a 2-shot lead over Stewart but bogeyed the 16th and 18th, while Stewart made a brave 5-footer at the last to force the Monday playoff. By the next day Hazeltine’s greens had baked out, turning crusty and unforgiving. Again, Simpson came to the last three holes with a 2-shot lead, and, again, it wouldn’t hold up. Stewart made a 20-footer for birdie on the 16th, while Simpson missed from inside 3 feet for bogey. Rattled, Simpson pulled his 4-iron on the 17th into the pond and scrambled for another bogey. Now, he was down a shot. Simpson’s approach at the 18th ran through the green, and with Stewart 5 feet away for par, he tried to chip in but couldn’t. Stewart won, 75-77.

U.S. Open Showcase

U.S. Open Showcase