June Books

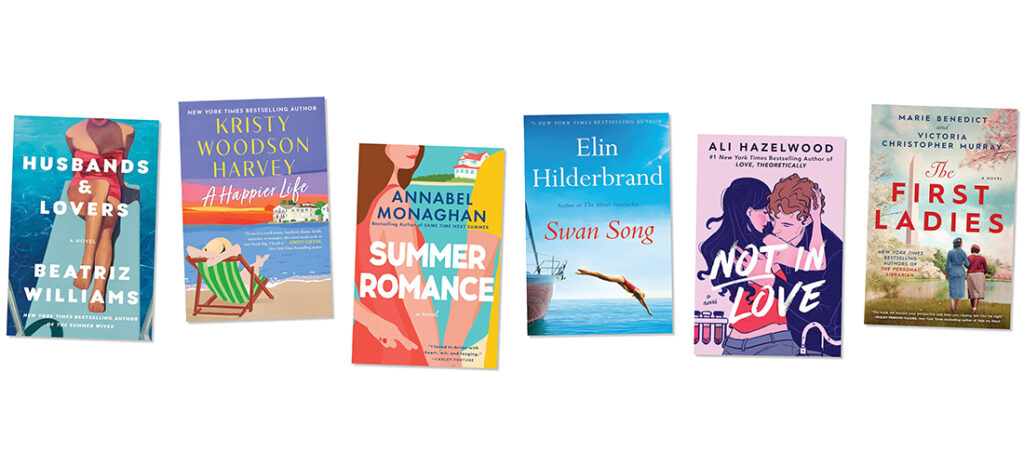

FICTION

Husbands & Lovers, by Beatriz Williams

Two women — separated by decades and continents, and united by an exotic family heirloom — reclaim secrets and lost loves in this sweeping novel from The New York Times bestselling author of The Summer Wives. New England, 2022: Single mother Mallory Dunne receives the telephone call every parent dreads — her 10-year-old son Sam has been airlifted from summer camp with acute poisoning from a toxic mushroom, leaving him fighting for his life. In a search for the donor kidney that will give her son a chance for a normal life, Mallory is forced to confront two harrowing secrets from her past: her mother’s adoption from an infamous Irish orphanage in 1952, and her own all-consuming summer romance 14 years earlier with her childhood best friend, Monk Adams, a fairytale cut short by a devastating betrayal. Cairo, 1951: After suffering tragedy beyond comprehension in the war, Hungarian refugee Hannah Ainsworth has forged a respectable new life for herself — marriage to a wealthy British diplomat and a coveted posting in glamorous Cairo. A fateful encounter with the enigmatic manager of a hotel bristling with spies leads to a passionate affair that will reawaken Hannah’s longing for everything she once lost. Timeless and bittersweet, Husbands & Lovers draws readers on an unforgettable journey of heartbreak and redemption, from the revolutionary fires of midcentury Egypt to the moneyed beaches of contemporary New England.

A Happier Life, by Kristy Woodson Harvey

The bestselling author of The Summer of Songbirds presents a tender and touching novel about a young woman who discovers the family she has always longed for when she spends a life-changing summer in North Carolina. Present day: Keaton Smith is desperate for a fresh start, so when her mother needs someone to put her childhood home in Beaufort, North Carolina, on the market — the home that Keaton didn’t know existed until now — she jumps at the chance to head south. The moment she steps foot inside the abandoned house, she’s confronted with secrets about grandparents who died in a car accident before she was born. And as she gets to know her charming next-door neighbor, his precocious 10-year-old son and a flock of endearingly feisty town busybodies, she soon finds she has more questions than answers. 1976: After meeting her adoring husband, Townsend, Rebecca “Becks” Saint James abandoned the life she knew and never looked back. Forty years later, she’s made a name for herself as the best hostess North Carolina has ever seen. Her annual summer suppers have become the stuff of legend, and locals and out-of-towners alike clamor for an invitation to her stunning historic home. Becks strives to make the lives of those around her as easy as possible, but this summer she is facing a dilemma that even she can’t solve. As both Keaton and Becks face new challenges and chapters, they are connected through time by the house on Sunset Lane, which has protected the secrets, hopes and dreams of the women in their family for generations.

Summer Romance, by Annabel Monaghan

The bestselling author of Nora Goes Off Script pens this romantic and hilarious story of a professional organizer whose life is a mess, and the summer she gets unstuck with the help of someone unexpected from her past. Ali Morris is a professional organizer whose own life is a mess. Her mom died two years ago, then her husband left, and she hasn’t worn pants with a zipper in longer than she cares to remember. No one is more surprised than Ali when the first time she takes off her wedding ring and puts on pants with hardware she meets someone. Or rather, her dog claims a man for her . . . by peeing on him. Ethan looks at Ali as if she’s a younger, braver version of herself. The last thing the newly single mom needs is to make her life messier, but there’s no harm in a little summer romance. Is there?

Swan Song, by Elin Hilderbrand

The New York Times bestselling author brings her Nantucket novels to a brilliant finish when rich strangers move to the island and social mayhem — and a possible murder — follow. Can Nantucket’s best locals save the day and their way of life? Chief of police Ed Kapenash is about to retire. Blonde Sharon is going through a divorce. When a $22,000,000 summer home is purchased by the mysterious Richardsons (how did they make their money, exactly?), Ed, Sharon and everyone in the community are swept up in high drama. The Richardsons throw lavish parties, flirt with multiple locals, flaunt their wealth with not one but two yachts, and raise the impossible hopes of everyone they meet. When their house burns to the ground and their most essential employee goes missing, the entire island is up in arms.

Not In Love, by Ali Hazelwood

Rue Siebert might not have it all, but she has enough: a few friends she can always count on, the financial stability she yearned for as a kid, and a successful career as a biotech engineer at one of the most promising startups in the field of food science. Her world is stable, pleasant and hard-fought — until a hostile takeover and its offensively attractive front man threatens to bring it all crumbling down. Eli Killgore has his own reasons for pushing this deal through, and he’s a man who gets what he wants — with one burning exception: Rue, the woman he can’t stop thinking about. Torn between loyalty and an undeniable attraction, Rue and Eli throw caution out the lab and the boardroom windows. Their affair is secret, no-strings-attached, and has a built-in deadline: the day one of their companies will prevail. A forbidden, secret affair proves that all’s fair in love and science.

The First Ladies, by Marie Benedict and Victoria Christopher Murray

The daughter of formerly enslaved parents, Mary McLeod Bethune refuses to back down as white supremacists attempt to thwart her work. She marches on as an activist and an educator, and as her reputation grows she becomes a celebrity, revered by titans of business and recognized by U.S. presidents. Eleanor Roosevelt herself is awestruck and eager to make her acquaintance. Initially drawn together because of their shared belief in women’s rights and the power of education, Mary and Eleanor become fast friends, confiding their secrets, hopes and dreams — and holding each other’s hands through tragedy and triumph. When Franklin Delano Roosevelt is elected president, the two women begin to collaborate more closely, particularly as Eleanor moves toward her own agenda separate from FDR’s, a consequence of the devastating discovery of her husband’s secret love affair. Eleanor becomes a controversial first lady for her outspokenness, particularly on civil rights. And when she receives threats because of her strong ties to Mary, it only fuels the women’s desire to fight together for justice and equality.

CHILDREN’S BOOKS

The Pelican Can! by Toni Yuly

Pelicans: lovely to watch and just as lovely to read about. This rhythmic picture book shares the beauty of a pelican’s day with scientific facts and delightful illustrations, making it the perfect read-together at the end of a long beach day. (Ages 2-6.)

Chloe and Maude, by Sandra Boynton

Adventures await with best friends Chloe and Maude. Art! Hiking! Even a tiny disagreement — everything is more fun with a friend. A perfect choice for fans of Elephant & Piggie or Frog and Toad who are looking for short chapter books. (Ages 5-8.)

If You Spot a Shell,

by Aimée Sicuro

Conch, whelk, scallop, moon snail . . . who hasn’t, on a beach day, seen hats and boats and spiraling wheels while looking at these stunning shells? If You Spot a Shell celebrates the beauty and creativity of beach art and is a great read-together after a long sun-washed beach day. (Ages 3-8.)

Trouble at the Tangerine, by Gillian McDunn

All Simon Hyde wants to do on the day his family moves into Tangerine Pines is settle into his forever home. But a fire alarm, a stolen necklace and a missing bracelet may send the Hydes on a path to seek a new home sooner rather than later. This charming mystery is the perfect summer story for animal lovers, adventure seekers and budding foodies. (Ages 9-12.) PS

Compiled by Kimberly Daniels Taws and Angie Tally.

J

J Night Bloomers

Night Bloomers  Puck & Co.

Puck & Co.