A giant of a man in a small town

By Bill Fields

On a mild December morning at Dixie Burger in Ellerbe, North Carolina, several customers of a certain age at a corner table are remembering someone who once sat among them, shooting the breeze and drinking coffee.

“Was grand marshal at the racetrack and lifted a girl on each arm like it was nothing.”

“Used to be booths in here, but he wouldn’t fit.”

“Ate 12 chickens in one day.”

When he wasn’t wrestling, making a movie or otherwise being André the Giant, the man sometimes called the “Eighth Wonder of the World” lived in Ellerbe for more than a dozen years. He enjoyed his time in the Richmond County town of about 1,000 people and loved to kill part of a day at the short-order restaurant, whose tall hamburger sign is the most visible landmark on Main Street.

“André could sit there and talk to people,” says Jackie McAuley, who was a close friend. She, along with her first husband, Frenchy Bernard, a former pro wrestling referee, managed André’s home and cattle ranch on Highway 73. “They treated him just like anybody else they would have seen in town. It wasn’t, ‘Oh, can I have your autograph?’ He was just an average person when he was home in Ellerbe.”

Notwithstanding the mannerly small-town treatment André René Roussimoff received, he was as close to being an average person as Ellerbe is to the Eiffel Tower. André the Giant — who died Jan. 27, 1993, at age 46 — was one of the most recognizable individuals of the 20th century. He was a genuine giant who emerged from the obscurity of his family’s farm in rural France, carrying armoires on his back up three flights as a Paris furniture mover, to become an iconic professional wrestler who drew large crowds around the globe and gained even wider fame playing Fezzik, the rhyme-loving giant in the 1987 romantic-adventure-comedy film The Princess Bride.

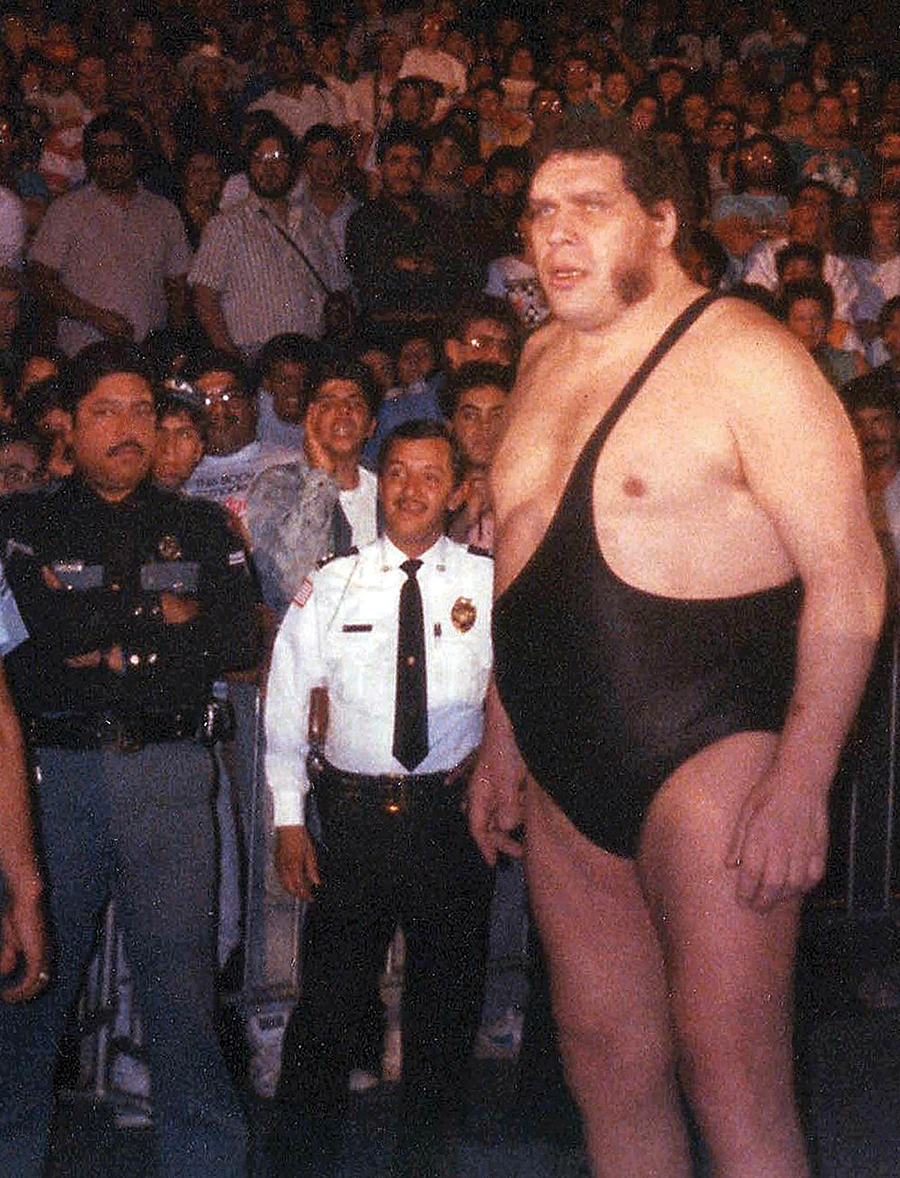

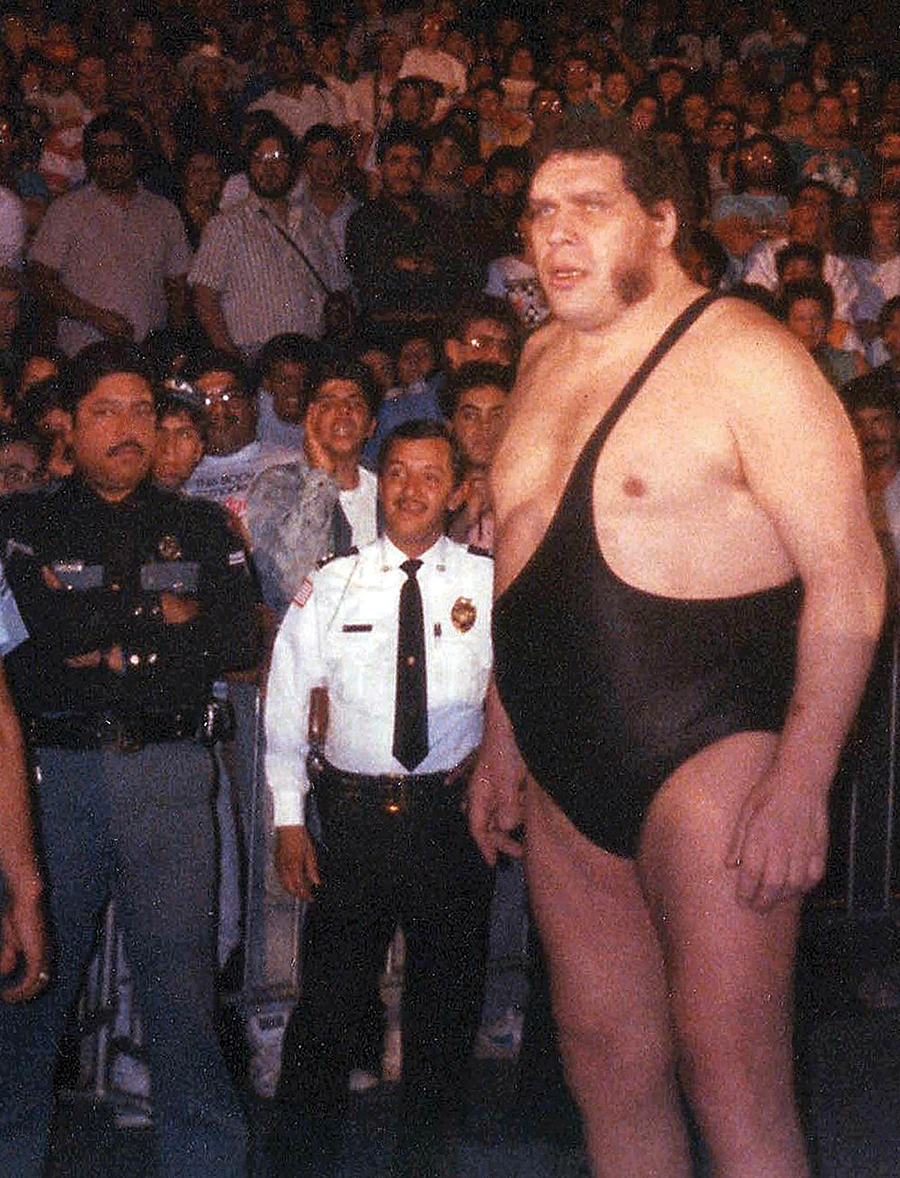

Standing 7 feet 4 inches — although there were skeptics who contended the wrestling hype machine bumped up his height so that he could be billed as the world’s tallest man — and weighing 520 pounds when he passed away of congestive heart failure, Roussimoff had acromegaly, a disorder that causes the pituitary gland to produce too much growth hormone in adulthood, resulting in unusual bone growth, including in the hands, feet and face.

His acromegaly was never treated, André refusing medical help when his condition was diagnosed, first during a visit to Japan in the early 1970s and again about a decade later at Duke University Hospital. Doctors there saved his life after fluid built up around his heart and wanted to operate on the pituitary gland to correct his acromegaly, but André, whose paternal grandfather also was outsized, wouldn’t agree to the procedure. “He said, ‘That’s how God made me,’ and he wasn’t going to change,” McAuley says.

To be around André once was to never forget his unique size.

His neck was 2 feet in circumference. It was nearly a foot around his wrist. A silver dollar could pass through one of his rings. In an exhibit devoted to André the Giant at The Rankin Museum of American Heritage in Ellerbe, a pair of his size 26 wrestling boots are on display. “Occasionally I could buy him T-shirts,” says McAuley, “if I could find 5 XL.” The Giant’s clothes were mostly custom tailored in Montreal or Japan to accommodate his 71-inch chest. Nellie Parsons, who ran Pate’s Cleaners in Ellerbe for 30 years, created custom hangers to accommodate the extraordinary width of his dress shirts.

In 1983-84, Burke Schnedl was a pilot for a charter service at what then was called Rockingham-Hamlet Airport and flew André to wrestling matches in cities throughout the Carolinas and Virginia — Greenville, Fayetteville, Richmond — in a twin-engine Cessna 402.

“We had to take out a seat in the back so he could get in,” Schnedl recalls. “The doorway is not that big, and he would have to turn kind of sideways. It had a bench seat on the side. André sat there and used a seat-belt extender to cover a space where two people normally would sit. He was just a lot of guy. When you shook his hand, it was like putting a single finger in a normal-sized person’s hand.”

By the time André was 12 years old, he already stood 6-foot-2 and weighed about 230 pounds, too large for the bus that transported schoolchildren in his village of Molien, 40 miles outside Paris. The playwright Samuel Beckett, who lived nearby in a cottage that Boris Roussimoff, André’s father, helped him construct, filled the void by driving André in his truck.

Before long André, the middle of Boris and wife Mariann’s five children, had outgrown not only vehicles but the sleepy landscape he saw as an impasse stopping his ambition to be famous. Boris Roussimoff didn’t understand, and at 14 André quit school, left home and set out on his own.

“His father told him he would be back soon working on the farm, and André had something to prove,” says Chris Owens, a repository of André the Giant knowledge who authors a Fan Club page on Facebook and has been intrigued by Roussimoff since he was a boy in the Midwest and saw him wrestle televised matches. “He didn’t want to stay in rural France. To me, he was always a guy going after his dream who became a classic success story.”

As a teenager in Paris, André’s preferred game was rugby, although he also got immense pleasure from pranking friends by rearranging their parked small cars while they were dining or drinking. He got 7 or 8 inches taller and gained nearly a hundred pounds before he turned 21, impressing professional wrestlers who noticed him training in a gym. They introduced him to their game, taught him some moves, and by the mid-1960s André René Roussimoff was getting paid to perform as Jean Ferre, Géant Ferré, The Butcher Roussimoff and Monster Eiffel Tower — and he was loving all of it.

“Many men were afraid to go in the ring with him, especially after he reached his 20s, because he was so large and strong,” André’s first manager, Frank Valois, told Sports Illustrated in 1981. “For all his height and weight, he could run and jump and do moves that made seasoned wrestlers fearful. Not so much fearful that he would hurt them with malice, but that he might hurt them with exuberance. He was incroyable.”

Promoters sent him to Great Britain, Germany, Australia, Africa and eventually Japan, a country where he first wrestled as Monster Roussimoff and would have some of his most avid fans the whole of his career. He began to be billed as André the Giant in 1973 by Vince McMahon Sr., founder of the World Wide Wrestling Federation, who discouraged André from being very active in the ring — even though his body at that point still allowed it — and to play up the fact that he was an immovable mountain of a man. “He was taught to wrestle as a giant,” says Owens. “He had a limited set of moves, and his matches generally were kept fairly short.”

Under McMahon, André made a large six-figure annual income and became the most famous professional wrestler in the world who traveled the majority of each year for two decades, his luggage belying his size. “He carried an unbelievably small bag for his wrestling gear,” says McAuley. “I don’t know how he packed as much as he did in that small bag. But if he was packing up at a motel and something didn’t fit, he would leave it behind. There were things left all over, I’m sure. I hope the maids discovered what they had.”

André was a creature of habit on the road because there was enough ducking and crunching just getting around that he didn’t like improvising unnecessarily. “If you gave me the name of the town he was in,” says McAuley, “I could tell you what hotel he stayed at, what restaurant he ate at and what bar he went to, and pretty much be right every time. There was security that came with the habit. He knew his size and where he could fit and couldn’t fit. If he had been going to a certain motel for 10 years and everyone else started going to a fancier place, he’d go to his usual one.”

Wherever André the Giant went, he amazed people with how much he could eat or drink if he was in the mood.

There are stories of his ordering every entrée on a menu, as McAuley witnessed one summer day in Montreal in the mid-1980s as she and Frenchy dined with André and several others. “We were at a small Italian place,” McAuley recalls. “André was in a good mood. He told the waiter he would like one of everything. The waiter said, ‘Seriously?’ Frenchy said, ‘Seriously.’”

Pro wrestler Don Heaton told the Los Angeles Times after the Giant’s death. “Everything came in twos,” he said. “Two lobsters, two chickens, two steaks . . . ”

There were nights of 100 beers, 75 shots, or seven bottles of wine lest any course of a special meal feel lonely.

“I can report with confidence that his capacity for alcohol is extraordinary,” Terry Todd wrote in his classic in-depth 1981 Sports Illustrated profile of Roussimoff. “During the week or so I was with him, his average daily consumption was a case or so of beer; a total of two bottles of wine, generally French, with his meals; six or eight shots of brandy, usually Courvoisier or Napoléon, though sometimes Calvados; half a dozen standard mixed drinks, such as bloody Marys or screwdrivers; and the odd glass of Pernod.”

Actor Cary Elwes recounted the making of The Princess Bride in his book As You Wish. He recalled going out barhopping with André in New York City after the movie’s premiere. The Giant’s beverage of choice that evening, as it sometimes was when they were filming in England, was what André called “the American,” a combination of many hard spirits.

“The beverage came, as expected, in a forty-ounce pitcher, the contents of which disappeared in a single gulp,” Elwes wrote. “And then came another. And they kept coming while I gingerly sipped my beer. We talked about work and movies, about his farm in North Carolina where he raised horses, his relatives back in France, and of course, about life. André was a man unlike any other — truly one of a kind.”

This unique character ended up living in Richmond County after coming with French-Canadian Adolfo Bresciano, who was billed as Dino Bravo in the ring, to visit Bravo’s stepdaughter in the late-1970s. She and her husband owned farm property in Ellerbe. André bought a nearby home, a three-story structure. The Bernards moved from Florida in the summer of 1980.

“We lived there and took care of things,” McAuley says. “If Andre needed something, Frenchy or I would get it. He just had the house for several years, with some cows and horses. Then the property down the road came up for sale, so we bought the ranch. Then he worked on getting the wooded property in the middle. André was in a bar in England once talking to a pilot who had Texas longhorns back home. So Andre decided we should have Texas longhorns, too.”

Some believed that Andre’s residence must have been built for his colossal frame, but it wasn’t. “Nothing could be further from the truth,” says McAuley. “The stairs were narrow. It was three floors. He didn’t care to have a house that was adapted to him because his life was in the real world. You’re not going to raise the light or the ceiling fan, because they’re not going to run into it. It becomes second nature. We really only did two things: We raised the shower faucet, so the water would hit him on the top of the head instead of the middle of the back, and we ordered him a large chair.”

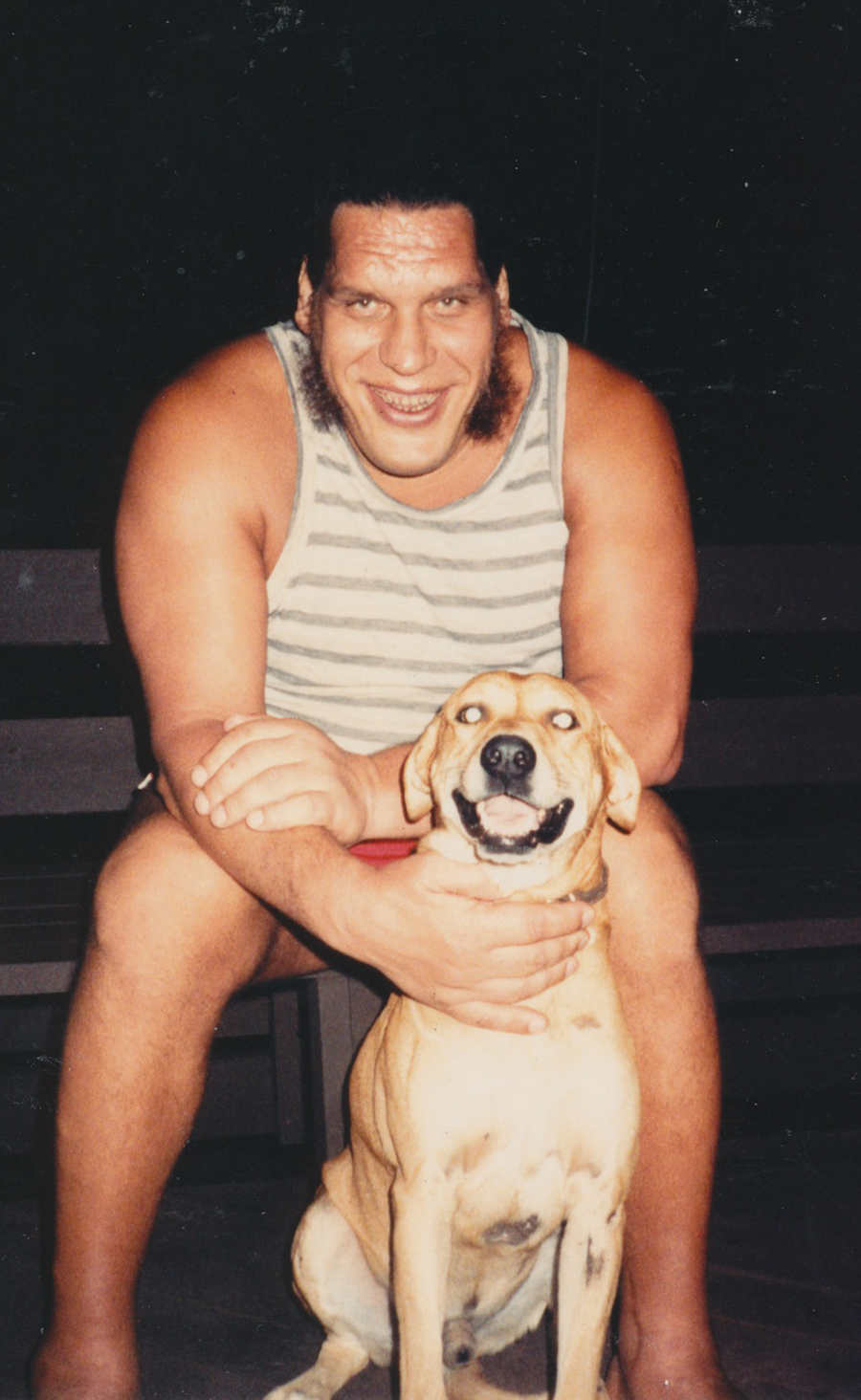

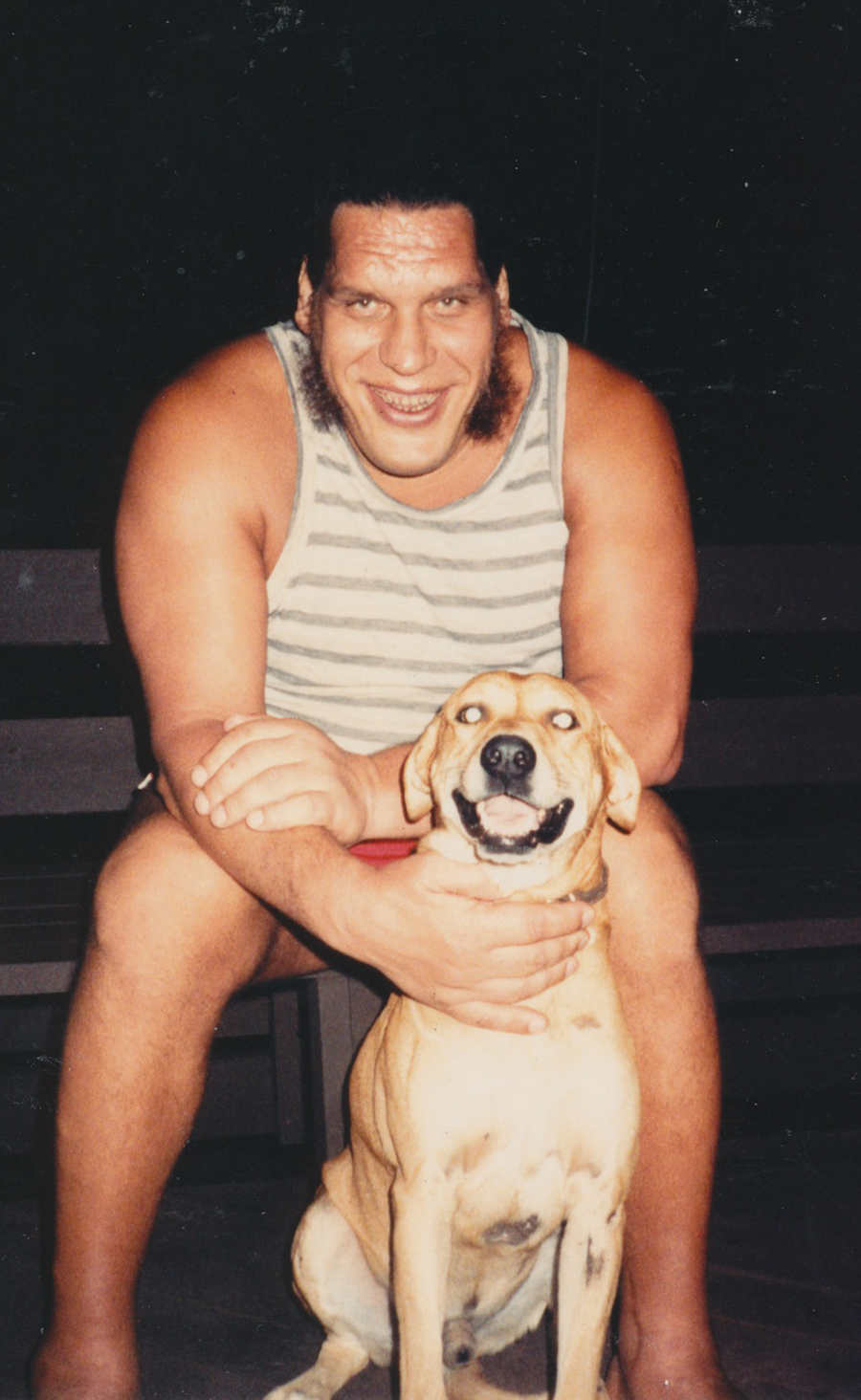

André would often sit in his chair with McAuley’s miniature dachshunds tucked by each tree trunk of a leg. He loved riding an all-terrain vehicle around his property. In the summers, André favored gym shorts, sometimes with a T-shirt, sometimes not. He was an expert cribbage player, owing to his good math mind and so many hours playing before wrestling matches. He didn’t venture far from his property when he was home, but loved his iced coffee at Dixie Burger, weekend meals at Little Bo Club in Rockingham, cookouts at neighbors’ homes, and checking in the hardware or feed stores.

McAuley says she never heard her friend talk about any regrets, that he never second-guessed anything in his life. “I have had good fortune,” André told Todd in 1981, “and I am grateful for my life. If I were to die tomorrow, I know I have eaten more good food, drunk more beer and fine wine, had more friends and seen more of the world than most men ever will.”

In addition to the scary episode of fluid buildup around his heart in 1983, he began to have other health problems during his years in Ellerbe. André had neck and back issues and surgeries, and he sustained a broken ankle in a 1981 match, wrestling on it for days until the pain became too much. To accommodate his size, the largest cast ever prepared at Boston’s Beth Israel Hospital was utilized.

An opportunity to be in The Princess Bride came along at a good time, since wrestling was becoming increasingly difficult because of André’s deteriorating body. “He could feel his wrestling career closing down,” McAuley says. “He had been so agile when he was younger. It was tough to watch him wrestle near the end of his life because of how hard it was for him to get around.”

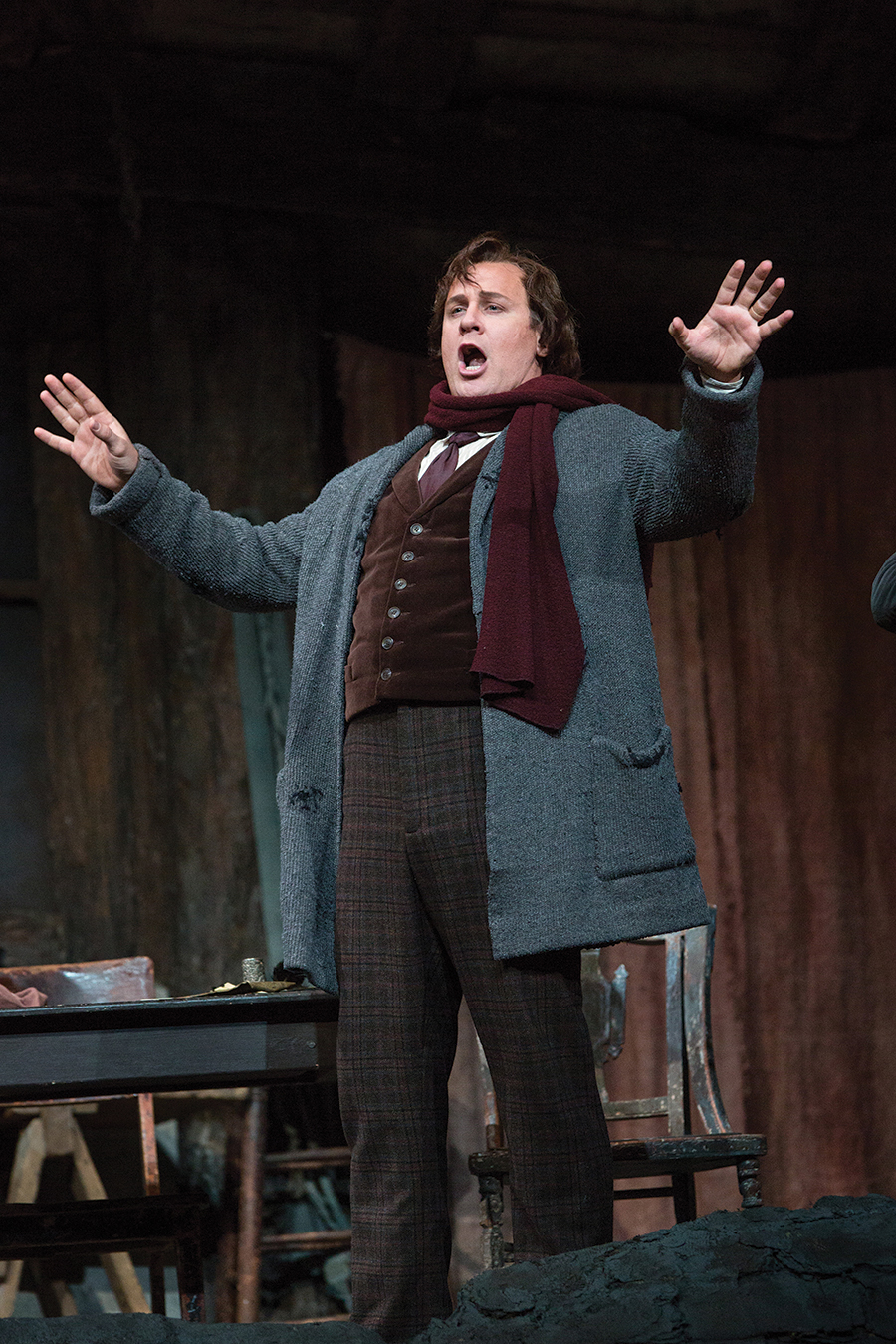

André had acted before — including portraying “Bigfoot” in a two-part episode of The Six Million Dollar Man — but he loved being part of the months-long production of The Princess Bride as Fezzik. “Doing Princess Bride gave him the most happiness,” says McAuley. “He’d call home and talk about all the silly tricks he was pulling, especially the week or so that Billy Crystal was there.” Around the set, as in his adopted hometown in North Carolina, André impressed with his disposition despite his acute pain.

“You could tell he was in tremendous pain, but would never complain about it,” actress Robin Wright remembered in As You Wish. “You could see it in his face when he would try to stand up from a seated position. But he was just the most gentle giant. So incredibly sweet.”

André never tired of watching The Princess Bride, but some of his friends did. “He drove the wrestlers crazy,” McAuley says. “Over in Japan, on a bus from the hotel to the matches, the boys would wait quietly until eventually he’d pull out the tape and say, ‘Let’s watch my movie again.’ They’d say, ‘Please boss. Not again.’ But they’d watch.”

The same year that The Princess Bride came out, André the Giant was headliner at WrestleMania III, where he was body-slammed and defeated by nemesis Hulk Hogan in front of a record crowd of 93,173 at the Pontiac Silverdome. He wrestled the last of his 1,996 matches (a record of 1,427-388-181) on Dec. 4, 1992 in Tokyo, his physical condition worsening. “His walking was compromised,” Owens says. “His posture had changed. He constantly needed something to hold on to or somebody to help him keep his balance.”

André’s last Christmas in Ellerbe was much different than the joyous first one a dozen years earlier. “He was just not himself,” McAuley says. “His color didn’t look good. I remember standing next to him and patting his stomach, which (had gotten larger). It didn’t dawn on me then that the first time that happened was ’83.”

In January 1993 André flew to France to be with his dying father. He stayed over after his dad’s death to be with his mother for her birthday on Jan. 24. On the 27th, André enjoyed a full day with boyhood friends from Molien. A driver was scheduled to pick him up at the Paris hotel where he was staying at 8 o’clock the next morning.

André didn’t pay attention to clocks, seldom wore a watch, and rarely was late. But he was not there to meet his driver, and he didn’t answer the phone in his room.

“The chain was on the door but they could see André in bed,” McAuley says. “The sheet was perfectly neat around him. He must have died as soon as he laid down, because André was one, when he woke up in the morning, the linen would be all shuffled around and when I would go to make his bed, I’d basically have to start over because the sheets would be in all different directions.”

The Roussimoffs were told André’s body was too big to be handled by any local crematoriums. A custom casket was constructed, and McAuley flew to France with her sister to accompany the body back to the United States so that André’s desire to be cremated, set forth in his will, could be carried out. Before returning, she visited Molien to meet André’s mother — “She was shorter than me and just adorable” — and siblings.

McAuley brought photo albums, pictures of “girls André knew” and his daughter, Robin Christensen Roussimoff, born in 1979, with whom he had little contact — a handful of visits and regular holiday phone calls. McAuley flew to the Seattle area once hoping to make André’s wish of a visit by his daughter to his North Carolina home a reality, but Robin, a young girl intimidated by the thought of a long trip to an unfamiliar place, declined.

André was returned to the land he had come to know so well on Feb. 24, 1993. Big-time wrestlers and small-town residents alike attended the ranch service, and after folks had spoken their remarks and paid their respects, Frenchy Bernard got on a horse with a saddlebag containing Andre’s ashes.

In death as in life André Roussimoff was larger than most. His remains weighed 17 pounds after cremation, nearly three times more than a usual adult male. They were spread in silence so different from the mayhem of the arenas and gyms where he had worked, finding their place, just like the man had. PS

I

I